My Parents Didn’t Come to My Graduation — They Said “No Time,” but They All Went to My…

Part One

My name is Tiffany Gordon, and at thirty-six I stood on the stage at UNC Charlotte, my fist wrapped around a master’s degree in law I had clawed toward for four years. The ceremony lights were bright, almost theatrical; the air buzzed with the relieved laughter of people who’d made it through. I lifted my eyes and found the three seats my parents had promised to fill—front right, two rows up, perfect sightlines.

Empty.

I checked again as if I’d miscounted the rows. Still empty. I had emailed the date to my mother, Deborah, six months in advance. I’d texted the start time to my father, Edward, a week ago. I’d mailed them a map of the auditorium because my dad “doesn’t believe in parking apps.” In every message, I’d tried to tuck in just a little of how much it meant to me—how many weekend mornings I’d traded for citations, how many nights I’d spent hunched over a kitchen table that was more casebook than wood.

“We’re so proud of you, Tiffany,” my mother had said last month, her voice warm but hurried, as if the words were stones she needed to unload so she could sprint elsewhere. When I pressed again earlier in the week—“You’re still coming, right?”—she’d said, “We have so much on, honey. You know Shannon just signed that new contract. She’s throwing a little thing,” as if my graduation were an inconvenience on her way to the latest stop on my sister’s self-produced tour.

Just a little thing. For Shannon, almost everything is.

The program’s opening bars pulled the graduates into motion. I walked where the alphabet told me to walk. I smiled at the right angles for the photographer and nodded at classmates who were easy with their joy because their people had shown up. In the crowd: bouquets, balloons, dads in baseball caps they’d pretend they hadn’t meant to wear. In my row: the steady click of heels, the careful shifting of gowns, the rustle of satin stoles. In my chest: an ache with corners.

When the dean called my name—“Tiffany Gordon, Master of Laws, with honors”—I crossed the stage on legs that had hauled me through more footnotes than I will ever reread. I took the diploma case. I moved my tassel. I smiled a photograph’s smile.

There was polite applause, the same as for everyone else. No one shouted my name. No familiar voice pierced the orchestral sameness. I told myself it didn’t matter. I had wanted this degree because I wanted it, not because anyone was keeping score. But when I sat down, the applause I’d imagined years ago still ringing unspent in my ears, something small inside me stood up and walked out the side door.

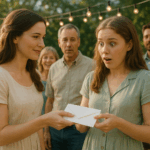

After the recessional, graduates poured onto the lawn. All around me: reunions. Fathers crushed sons in bear hugs. Mothers fixed caps like they were fixing everything. Little siblings bounced on their toes with balloon strings wrapped around their wrists like new bracelets. I stepped to the edge of it and waited for my phone to buzz with a text—Parking took longer than we thought! Be right there. What I got instead was a photograph I didn’t want to see.

Shannon had posted it an hour earlier, while the university president was talking about perseverance. In the photo: my parents in her living room, flanking her like bookends, raising wineglasses. The caption: “Celebrating my big contract win with my favorite people.” In the background, a banner—$10K Wedding!—slouched above the mantle. My mother’s smile was wide. My father’s arm was around her shoulder. I pinched the screen and zoomed and zoomed again, as if the pixels could explain the geometry of absence.

My throat tightened. It would have been easier to believe there had been a car accident, a mix-up, a flat tire, a mislabeled calendar. But there they were, in real time, choosing the little thing.

I walked to the parking garage with my diploma case tucked under my arm like something breakable. I had booked a celebratory dinner at a tiny Italian bistro downtown—the one with the good ravioli and the string lights that turn everyone young—but the thought of sitting at a table I had set for four felt like a joke with no punchline. I slid into my car and let the autolock thud like a period.

Then my phone lit up with a text from my mother: We need to talk urgently.

Below it: thirty missed calls from my father in just under an hour.

The mixture of anger and dread felt like swallowing ice. I pulled into a gas station and called my dad back.

“What happened?” I asked, and surprised myself with how steady I sounded.

“It’s Shannon,” he said, in a voice I’d only ever heard when he slammed his thumb in a drawer. “She fell down the stairs at her party. They’re taking her into surgery. Your mother and I are at the hospital. We need you here.”

Which hospital, he told me. I sat there under the fluorescent glare for one breath and then another, weighing my graduation gown folded in the backseat against the family gravity that has pulled me my whole life. Five minutes later I was driving toward Carolinas Medical Center with the Charlotte skyline giving me its usual combination of optimism and warning.

The emergency room waiting area had its own weather—too bright, too cold. My parents stood up when they saw me. My mother’s tissue was wet along the seams. My father’s mouth was a hard line that couldn’t hold much.

“What happened?” I asked again, sharper this time.

“Shannon’s concussion is mild,” my mother said. “But she broke her femur. The doctor said it’s a complicated fracture. They need to put a rod in.” She swallowed. “They need a deposit. Fifty thousand.”

The number sat between us like a third chair. It took my brain a second to run its fingers along the edges. Fifty thousand. I had sixty in savings—every bit of it scraped together by saying no to everything except work. My plan had been simple in the way all hard plans are: open a small practice, hang my own shingle, help the kind of clients I’d been trained to help: single parents fighting for custody, grandparents who’ve been caregivers for years, guardians who want to do the right thing and need a map.

“We don’t have that kind of money,” my father said, which I knew. “Her work doesn’t come with good insurance,” which I also knew. “You’re the only one who can—”

“You’re asking me to pay it,” I said, and the word ask wore a suit of expect. “You skipped my graduation to drink with Shannon, and you’re here now because she was drinking at her own party. You want me to give you almost everything I’ve saved for my future to fix her present.”

My mother flinched. “We wanted to be at your ceremony,” she said. “We did.” Her voice broke on did like a twig. “Shannon said this was critical for her career. She said the ceremony was just a formality.”

“She said that?” I asked. My voice came from somewhere lower than my throat.

My mother nodded. My father didn’t look at me.

There are moments you think might be misunderstandings until you hold the receipts. I pulled out my phone and scrolled through an inbox cratered by finals. There: an email chain my mother had forwarded weeks ago, with my address accidentally left in. I tapped it open.

From: Shannon. Subject: Party! The paragraph bloomed like mold: “My party is a huge career move. Tiffany’s graduation is just a formality. She won’t mind if you skip it to support me.”

I turned the screen toward my mother, toward my father, toward the whiteness of the waiting room walls. My mother pressed a hand to her mouth. “I thought she was just excited,” she said through her fingers. “Tiffany, I’m sorry. I didn’t…we didn’t…” My father closed his eyes. When he opened them they were old.

A nurse passed with a chart. Somewhere down a hall a monitor beeped in an impatient tempo. I looked at the email again so I wouldn’t say something I wouldn’t want to take back.

“She planned it,” I said. “She wanted to be the headline on my day, and you let her be.”

“We made a mistake,” my father said. “Shannon needs this surgery. Please.”

In the space between please and anything else, something aligned in me that had been tilting for years. I had asked for their presence and received their absence. They had asked for my approval and received it by default because I wanted to be a good daughter. They were asking for my money now—not as a favor, but as a duty.

I felt my jaw unclench.

“I’ll pay,” I said. My voice had the steady flatness of rain.

Relief broke across my mother’s face like light through a slit. My father exhaled with the sound of old pipes.

“But hear me,” I said, looking at both of them so I’d remember later that I had. “This is the last thing I will do for this family. You chose a party over my ceremony. Shannon chose herself. I’m choosing me. There won’t be any next time. Not a smaller loan. Not a larger one.”

“Tiffany—” my mother started.

“No,” I said, and walked away to the billing office before my heart could second-guess my mouth.

I signed the papers with a hand that didn’t tremble and watched fifty thousand become zeroes and ones in someone else’s column. Then I drove home and canceled the restaurant reservation I had made for a table we were never going to fill. The server said, “I’m sorry, ma’am,” and I believed she meant it more than my mother had meant we’re so proud of you.

At my apartment, I sat on the edge of my bed and listened to the hum of the refrigerator and the smaller sound of my own breath. When the sun slid along the wall, I picked up my phone, blocked my parents’ numbers, blocked Shannon’s, unfollowed them on every platform, and put my phone face down like closing a book I had outgrown.

At the law firm the next day, I explained to my boss—clearly and briefly—that I would be leaving in two weeks. I spent those two weeks not thinking, which is its own kind of thinking. I packed my apartment in boxes that were heavier because I was lifting them alone. I signed a lease on a small office in Miami and a smaller apartment within walking distance of it. I loaded the boxes into a moving truck whose driver called me ma’am and told me he had a daughter my age and asked me if I was sure I didn’t want help. I said I was sure.

I left Charlotte with everything that fit and a piece of paper in my glove compartment I still have not framed.

Part Two

Miami smelled like salt and heat and hope if you can smell hope. The first morning, I walked into the office I had leased with the last ten thousand dollars in my account and flipped on a light that made the scuffed baseboards look honest. I had a used desk, a secondhand bookshelf, law books that I both love and resent, a printer that does its best, and a coffee machine that wheezes like it’s been through something. I made a sign for the window: Gordon Family Law. Underneath: Custody • Guardianship • Estates. Underneath that: By Appointment.

Word travels in legal circles faster than you think. A family friend of a former client called. Then a woman who’d heard I was “the one who explains things without making me feel dumb.” Then a guy whose brother-in-law had taken the refrigerator when he moved out. I took the cases I could. I referred out the ones I couldn’t. I charged enough to pay myself; I wrote off what I needed to in order to sleep at night. I won some. I lost some. I learned to tell clients the truth even when their faces told me they wanted to buy a lie.

My parents tried to reach me for a while—voicemails I let pile up the way people let junk mail pile up, emails I marked as spam before I saw the subject line. A cousin sent a “you didn’t hear it from me” text: People are talking. In their quiet suburb, the story had slid across potlucks and prayer chains. It is hard to hold your head high while also holding the knowledge that you chose your loud daughter’s party over your quiet daughter’s degree. It is harder when your loud daughter’s party ends with a fall that sounds like cautionary tale. People who used to clap for them clapped less. People who used to give my mother the better chair at church let her find one on her own.

As for Shannon, a client at her party had been less impressed by her “networking with wine” strategy than she hoped. Charlotte’s event world is tight, tidy, gossipy. It didn’t take long for she fell down the stairs at her own gig to become a curse you didn’t want attached to your budget. She lost a fifteen-thousand-dollar corporate gala before she’d signed the contract; the bride who’d been using her for place cards “found someone who can commit without…so much drama.” Months with a healing femur and a fuzzy brain will teach you how to sit with yourself. Whether they teach you anything else is between you and your mirror.

I didn’t let any of that in unless it came stuck to something I needed—like when a prospective client told me he’d heard I was “no-nonsense” and I thanked whatever channel had loosed that phrase into the world. I focused on my cases and the light through my office blinds at three p.m. and the ocean when I could get to it and a calendar that was mine in every box. I bought a cheap ficus. I learned which bodega on my block sells the good empanadas. I learned the exact amount of music it takes in the morning to make me feel awake without burning the mood I need to meet a client who’s been surviving on adrenaline and bad advice.

Six months into Miami, I took on a case I will keep in my heart forever: a woman named Marisol whose ex had decided the baby he’d ignored for a year was suddenly an accessory he could use to hurt her. I sat across from her while her hands worried a tissue to lace and said, very carefully, “Here is what we can ask for on Tuesday. Here is how I will ask. Here is how he will try to make you small. Here is every way I know how to make that not work.” When the judge decided in her favor, she squeezed my fingers so hard I thought I’d lose circulation and said, “You saved my life,” which attorneys always want to pretend is a metaphor. Sometimes it isn’t.

On a damp Thursday, I got an email from a colleague about a legal aid clinic that needed extra hands. I signed up for a Saturday slot and told my assistant—who is twenty-two, brilliant, and the first person I hired when I could afford to hire anyone—to hold calls. I spent the morning telling people exactly what they could and couldn’t do, and it felt like church.

After, I walked past a bakery whose window was crowded with cakes that all wanted to come home with a child and thought about the life I had chosen when I pressed confirm transfer in a billing office under a fluorescent light. The grief is smaller now, and it knows its place. The anger is a compost heap—I turn it with a long fork and use what it becomes in the garden I’m trying to grow.

In late spring, an older woman came into my office and asked if I could help her write a will her daughters wouldn’t fight over. “They act like I’m a fruit tree,” she said, wry. “They’re already arguing over pears I haven’t even grown.” I told her we could make something clear and clean that would outlast their worst day. When she left, she touched the doorframe the way people do when they’re trying to memorize a place by hand and said, “You look like someone whose parents must be so proud.” I smiled, because she meant to give me a flower, not a thorn. “Some days,” I said. “Some days I am.”

One afternoon, I opened my mailbox and found a small envelope with my mother’s handwriting—a script I had known since spelling tests were a frontier. Inside: a card that said nothing but I’m sorry. No but. No ask. No reheated justification. I sat on my couch and let the apology be exactly as big as it was. Then I put the card in a drawer with a few things I keep when I don’t know yet what they mean—a pebble from a beach I love, a photo of me with a ponytail and a mock trial trophy, a printout of the first dollar I made on my own letterhead.

A week later, another envelope: a single page, Shannon’s handwriting, messier than my mother’s, steadier than when we were kids. I was cruel. I wanted to be the sun. You were not a cloud. Thank you for paying for the surgery. No ask. No calendar invite to anything. I didn’t reply. I did a thing I didn’t expect myself to do: I put that note in the same drawer.

I don’t know exactly what comes next with them. I know what doesn’t: loans, rescues, showing up to ceremonies alone in the hope that someone else will notice I have turned myself into someone I like. I know that blood is not a hall pass. I know that my office smells like coffee I pay for with work I know is good. I know that some days, when I lock up and the sun is a soft orange smudge over a city that has made me welcome, I wish their faces were in the crowd that cheers me on now. I know other days I am glad they aren’t, because the crowd that is there is made of people I chose and who chose me.

In June, I got invited to speak at a neighborhood center on Boundaries and Family: What the Law Can and Can’t Do. I wore a black dress that makes me stand taller and talked for twenty minutes about legal tools—protective orders and custody agreements and how to write a will that screams in a language the court understands. Then I put the microphone down and talked for ten minutes about the tools we forget we have: the word no and the word enough and the word mine. During Q&A, a woman about my age asked, “How do you deal with the guilt?” I answered the only way I can: “Guilt will tell you to build a house in it. Don’t. Pitch a tent when you have to. Learn the weather. Then go home.”

A month later, I stood in a doorway watching a client sign papers that would make her life easier and thought about a girl who sat alone after a graduation and decided not to beg for a table where no one wanted to sit with her. The girl is still here. She lives in my spine and in the tight corners of contracts I draft and in the way I speak my own name when someone asks, And what do you do?

A summer thunderstorm rolled in the way they do here: quickly, theatrically, without much interest in my calendar. I watched rain stripe the street. My assistant put a mug of tea on my desk, the one with the chip I never bother to turn to the back because the chip is honest. I opened a new file. I answered a new email. I put on a playlist that makes me feel like the version of myself I liked even before I learned to love her.

If you want the tidy epilogue: my parents have started telling people their youngest is an attorney in Miami. Sometimes they catch themselves before they add independent like it’s a strange adjective on that noun. Shannon is working again—smaller events, more water on the table. She sent me a photo of a modest reception she’d put together in a church hall. The caption said, Baby steps. I hearted it and put my phone face down and finished drafting a petition.

And if you want the truth that isn’t tidy: the hurt shows up sometimes like a song from another era you didn’t ask to hear. When it does, I let it play. Then I change the station.

On the anniversary of my graduation, I bought myself flowers. Not roses—too on the nose for a family lawyer with a soft spot for metaphors—but ranunculus, because they look like the inside of a secret. I put them in a jar on the windowsill of my office and sat with a client who was trying to decide who she wanted to be on the other side of a bad decade. We drew out a plan. We circled the dates. When she left, she said, “You get it,” and I said, “I do.”

That evening, I walked along the water with the air doing that soft thing it does here at dusk. I thought of the auditorium, of the empty seats, of the phone lighting up with a text that had never been about me. I thought of the billing office and the click of a keyboard that had changed my life. I thought of a sign in a window that says Gordon Family Law and a door I open every morning with a key no one gave me.

This is the ending, clear as glass: my parents didn’t come to my graduation. They went to my sister’s party. I paid for my sister’s surgery and for the privilege of leaving the old script on the table where it died. I moved to a city that didn’t know me and let it teach me what I had always tried to be told by people who couldn’t say it: You are enough. I built a practice and a life that do not require me to audition. And if anyone ever tells me my milestones are “just a formality,” I will smile and hand them a business card—because that’s when you know the law, and your own, are on your side.

END!

News

On My Birthday, My Dad Texted: “Don’t Expect Anyone To Show” Then I Saw The Group Photo: All… CH2

On My Birthday, My Dad Texted: “Don’t Expect Anyone To Show” Then I Saw The Group Photo: All… Part…

At The Family Party, I Gave My Sister a Sealed Envelope: 6 Months of Covered Rent — But Then… CH2

At The Family Party, I Gave My Sister a Sealed Envelope: 6 Months of Covered Rent — But Then… …

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Kicked Me Out Of The House Just For Defying My Sister. CH2

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Kicked Me Out Of The House Just For Defying My Sister — So I……

My Parents Gave My Sister a $860K Home. Then, They Came to Take My House. But When I Refused… CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister a $860K Home. Then, They Came to Take My House. But When I Refused… …

At Family Dinner, My Dad Sneered, “Still Living Off Us” The Whole Family Laughed And Then… ch2

At Family Dinner, My Dad Sneered, “Still Living Off Us” The Whole Family Laughed And Then… Part One I’m…

My Parents Mocked Me at My Sister’s Wedding — But Everyone Went Silent When My Husband Arrived. ch2

My Parents Mocked Me at My Sister’s Wedding — But Everyone Went Silent When My Husband Arrived. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load