My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter … Imagine lying in a hospital ICU, machines keeping you alive, and when the nurse calls your parents, they choose dinner with your brother’s girlfriend over rushing to your side.

Part I

The room did not feel like mine, yet it held my life hostage. Every sound in the intensive care unit was amplified—the steady drip of an IV, the mechanical hum of fluorescent lights, the faint squeak of shoes on polished linoleum. Time moved differently here, marked not by clocks but by machines that blinked and beeped in place of certainty. The air smelled faintly of antiseptic and lemon, a sterile mix that clung to my lungs, reminding me I was not in control anymore. I lay there tethered by wires and tubes, unable to steady my breathing. A nurse pressed two fingers to my wrist and whispered, “Stay with me.” Her voice was soft but urgent, as if sheer will could keep me from slipping away.

I had no memory of the fall, only fragments—the gray carpet at work, the blue threads in its fibers that I stared at while the world spun sideways; sirens wailing; a ceiling rolling above me like film frames clicking too fast. Now I was a patient, a case, an entry in a system. And yet I was still someone’s daughter. That thought clung to me more desperately than the oxygen mask strapped across my face. When the nurse asked about my emergency contacts, my voice, thin, raspy, distant, answered automatically: “My parents.”

She dialed and switched the phone to speaker so her hands could remain steady against my failing pulse. I braced for the sound of home, a comfort I had always longed for but rarely received. “Hello?” My mother’s voice rang out, light and cheerful, the clinking of dishes in the background. I imagined a restaurant somewhere in town—silverware against china, the chatter of waiters refilling glasses. “This is County ICU,” the nurse explained calmly. “Your daughter has been admitted. We need you to come immediately.”

There was a pause just long enough for me to believe. Then my mother’s voice floated back, unshaken, as though she were merely rearranging her evening plans. “Oh, we’re at dinner with our son and his new girlfriend. Is it urgent?”

The nurse’s tone sharpened. “She collapsed at work. We’re concerned about internal bleeding. She may not survive the night.”

The silence that followed could have shattered me, but it only confirmed what I had always known. My father finally spoke, his voice firm but detached. “We’ll pray.”

I stared at the monitor above my bed, its bright green digits pretending the world was orderly. But I knew better. In that sterile room, I realized something that would change me forever: I was fighting for my life, and my parents had already chosen dessert over me. As the call ended, the silence in the ICU seemed louder than any alarm. The nurse’s jaw tightened, her eyes soft with the kind of sorrow only strangers offer—pure, unburdened by history.

“Is there anyone else we should call?” she asked. “Friends, extended family?”

I shook my head, too tired to explain that love in my family had always been conditional. I thought back to the countless moments when I had tried to earn it. Birthdays where I planned the cake and the decorations myself because my parents forgot the date. Holidays where I cooked dinner while my brother basked in the praise for merely showing up with a smile. I remembered the credit card bills they left piled on the kitchen counter—bills I quietly paid off when I got my first steady job. They called it being responsible. I called it survival.

My brother was the golden child, the one who could do no wrong. He brought home trophies from Little League and they celebrated as though he had won a Nobel Prize. When he got a haircut, my mother’s face lit up as if the sun had entered the room. But when I earned top grades, worked overtime, or simply kept the family functioning, it was met with silence. A nod at best. In their eyes, his mere existence was enough. Mine was an obligation—visible only when it failed.

I learned young that in families like ours, daughters often became the quiet scaffolding holding everything up. I saw it in neighbors, too: sons praised for ambition while daughters carried groceries, babysat siblings, managed the chaos in silence. It was tradition dressed as love, a pattern passed down unchallenged because no one wanted to admit it was neglect. And yet I stayed. I kept hoping that one day my parents would see me. That they would look past my brother’s shadow and recognize the daughter who had been their safety net, their accountant, their planner, their caretaker.

But that night, as I lay strapped to machines, the truth carved itself into me more sharply than any scalpel could. They didn’t come. They chose dinner.

The monitor kept beeping in steady rhythm. Each sound like a tally mark on a ledger. Debit: every sacrifice I had made for them. Credit: the silence I got in return. Balance: a daughter lying in a hospital bed alone.

A nurse adjusted my IV, her eyes searching mine. “Are you okay?” she asked softly. I almost laughed at the question. No, I wanted to say. I am drowning in a lifetime of being unseen. But what came out instead was colder, sharper. “I’m making sure they’ll never forget this.”

Beneath exhaustion and heartbreak, something else began to form—not rage, not even grief, but clarity. I finally understood my place in their story, and it was no longer one I wished to play.

The hours that followed were suspended between life and death. Every breath felt like pulling on a frayed rope, my palms raw from the effort of simply staying alive. Yet my mind was sharper than it had ever been, honed by betrayal. The nurse asked gently if I wanted to dictate anything, just in case my strength failed before morning. She handed me hospital stationery and a pen, both light in her hands but heavy in mine. I studied the paper against the cold metal railing of the bed, the IV dripping beside me like a metronome.

I began not with Mom or Dad, but with their full names—legal, precise, almost surgical. It was a boundary etched in ink, a declaration that this letter would not bend to sentimentality. The first line came easily: You will not recognize the person writing this. The pen scraped softly across the page. Each stroke pulled from years of silence; each word was weighted with the things I had swallowed whole.

I wrote of the call—the exact words the nurse had spoken, the pause that followed, the way my mother’s voice carried the clinking of wine glasses instead of urgency. I wrote of my father’s answer: We’ll pray. It wasn’t anger that guided me; it was precision. I wanted them to see the truth without the cushion of memory to soften it. I wanted the black-and-white clarity of words on paper to confront them in a way my voice never could.

My hand cramped, letters slanting as fatigue tugged at me, but I pushed through. I underlined one sentence twice: You did not come.

I thought of every sacrifice I had made for them—the bills paid, the trips booked, the meals cooked while my brother basked in unearned praise. I thought of the birthdays where I smiled at my own cake alone. And then I thought of the choice they made that night, and I realized this letter was no longer just words. It was my verdict.

The nurse returned, adjusting the monitors, her eyes flicking to the page. “You okay?” she asked again.

“I’m making sure they’ll never mistake what happened,” I whispered.

She didn’t press further. Maybe she understood. Maybe she pitied me. It didn’t matter. This wasn’t for her.

When I finished, I folded the paper once, then again, tucking it beneath the thin hospital pillow. My hand lingered there, pressing it into place as though sealing a contract. The note was more than ink. It was the line they would never cross back from. Staring at the ceiling tiles, tracing the faint grid above me, I realized survival wasn’t just about making it through the night. Survival was deciding who did not get to follow you into tomorrow.

Seven days blurred together in the ICU, measured not by sunrises or sunsets but by the shuffle of nurses’ shoes, the gentle roll of carts down the hallway, and the steady chorus of machines. My parents never came. Not a single call, not even a message to ask if I was alive.

But others did. My manager stopped by carrying a cardigan from my desk because she knew I hated hospital gowns. A college friend drove three hours just to sit with me for twenty minutes. Even my neighbor—someone I had barely spoken to—brought a book she thought might comfort me. Strangers, acquaintances, friends—they filled the empty spaces my family had left hollow.

By the third day, I stopped wondering if my parents would appear. By the fifth, I stopped hoping. By the sixth, I started to imagine what it might feel like to never see them again. The truth was startling: it felt lighter.

On the seventh morning, the doctor smiled. “You’re stable enough to go home tomorrow.” My body was healing, though it carried scars that weren’t visible on skin. That night, as the city lights glowed beyond the blinds, I stayed awake long past visiting hours. My discharge papers were already signed, my bag packed neatly by the nurse. All that remained was the letter under my pillow.

Sometime after midnight, I heard footsteps in the hallway—two sets, slow, deliberate, reluctant. My body tensed. I didn’t need to see them to know they were here, but I did not stir. I let my breathing slow, steady, pretending to be asleep. The curtain never moved. They hesitated and then walked away. I wanted it that way. I wanted them to come in the morning when the bed would be empty, when they would reach for me and find only absence, because sometimes absence is louder than presence, sharper than words.

At dawn, the nurse helped me dress—soft sweater, loose jeans, shoes that felt foreign after days in bed. “Are you sure you don’t want to wait? I heard they might visit today,” she said gently.

“I’m sure,” I told her.

I left the bed made perfectly, sheets smoothed, pillow fluffed. In the center, I placed the folded letter. No envelope, no seal, just the truth waiting to be read. Walking through the polished corridors, each step felt like turning a page I had been trapped on for years. The sliding glass doors opened to the cool morning air, the scent of rain on concrete filling my lungs like freedom.

Outside, my friend Marissa was waiting with her car. She didn’t ask questions. She just took my bag, opened the passenger door, and drove.

Meanwhile, somewhere behind me, I knew they had arrived. I could see it in my mind—the click of my mother’s heels on linoleum, the nervous glance of my father as he stepped into the room, the small pause when they saw the bed empty, the way their eyes would scan, searching, until they found it: the single folded sheet on the mattress. They would expect forgiveness or at least gratitude. Instead, they would read each word I had written in that sleepless night—each sentence recounting their choice. By the end, they would understand this was my goodbye. No forwarding address, no open door, only silence, heavy and permanent.

Part II

Marissa drove in silence, her hands loose on the wheel, her eyes fixed on the road. She didn’t ask what I’d written; she didn’t need to. Some things are too heavy to hand off, and some silences are sacred. As the hospital faded in the rearview mirror, I felt an unexpected release, like the air inside had been rationed and now the whole sky belonged to me. For the first time in years, I wasn’t holding my breath, waiting for someone else to decide my worth.

Her apartment smelled like laundry and cinnamon. The guest room was simple but warm—fresh sheets, a vase of lavender on the nightstand, a mug of tea waiting for me in the morning. The kind of gestures my parents never thought to offer. The kind that required no bloodline—only care.

My phone lit up constantly: calls, texts, emails from my parents. Some pleading, some defensive, all circling the same wound. I didn’t answer. That was the truest revenge—not in blocking them but in letting them speak into a silence that would never break. I pictured them late at night, my father rereading the letter under a dim kitchen lamp; my mother’s fingers tightening on the edges of the page. They would carry it forever. Every holiday, every family dinner, every time they glanced at my brother and wondered why their daughter had walked away, that single line would haunt them: You taught me my worth the night you stayed at dinner.

Marissa took days off to shuttle me to follow-up appointments. She packed crackers in her purse for my queasy stomach and learned how to fold my discharge instructions into a slim folder that never left her tote. The first time she helped me up the stairs and I leaned hard into her shoulder, she grinned and said, “Don’t worry, I’ve carried heavier things.” I believed her—not because I thought I was light, but because she made the carrying feel like choice, not obligation.

At night, lying on her couch under a knitted throw, I let myself remember childhood with the kind of clarity that stung. The way Dad would turn the television up when I spoke; the way Mom would ask if I was “overreacting” whenever I cried. The day my brother dented the side of the family car, and I took the blame so he could still make it to practice. The time I needed a ride to a scholarship interview and Dad said the traffic was “too much of a hassle,” so I took two buses and arrived breathless, apologizing for being late to a man who would later write that I had “remarkable resilience.” My brother arrived to dinner late that night, flung his keys on the counter, and was praised for his work ethic.

There were tender moments too—because love is crueler when it isn’t absent, just rationed. The afternoon Mom taught me to make soup from scraps, her hands steady as she sliced onions paper-thin. The rare night Dad laughed with me over a movie, the sound boyish and unburdened. These memories made the rest bearable for years. They were coupons I kept redeeming, hoping they hadn’t expired.

Healing moved slower than the movies suggest. The bruises bloomed and then faded. Headaches arrived like uninvited guests and left when they pleased. My body relearned the rhythm of sleep. I changed my emergency contact from “Mom” to “Marissa,” and the nurse who entered it in the system glanced up, eyes kind. “Good choice,” she said. I nodded and didn’t cry until I got home, because some paperwork is an autopsy.

On the fifth day after discharge, I opened my email and found a message from my brother. The subject line was a shrug: Hey. The body of the message was shorter than the subject. “I heard you were in the hospital. Mom said you’re mad. You know she gets anxious. Things get complicated. Anyway, hope you’re feeling better. You should meet Becca sometime—she’s awesome.”

I read it three times, then closed the laptop. I wished I could say I was shocked, but entitlement rarely surprises you; it merely confirms itself. I brewed tea and watched steam climb into the air and disappear, as if proof that not everything needs to be held.

Marissa’s cat, Alabaster—named for his color and his inexplicable dignity—began sleeping at my feet as if self-appointed to night shift. On the seventh night, he moved to my pillow, pressed his forehead to mine, and purred. It was the first time since the ICU that I slept without waking.

A week later, I stood in the small kitchen and wrote a second letter. Not to my parents or my brother, but to my future self. It began: If you ever doubt your choice, remember the moment you listened to the beep of a machine and realized you were more alone with them than without them. It listed the names of those who had shown up. It recorded the shelf where Marissa kept the mint tea and how she’d labeled it “for breath.” It reminded me that freedom can feel like a fall before it feels like flight.

I was learning the geometry of boundaries: the angles where you say no; the soft arcs where you say maybe; the straight line of never again. My therapist, a woman with a voice like a quiet radio, asked me to name what I wanted. The list surprised me with its ordinariness: a living room that never feels like a stage; friends who answer texts and ask questions back; holidays that don’t require me to edit myself for the comfort of others; a family of choice that’s small and stubbornly kind.

One afternoon, I walked past a bakery and bought a single slice of cake with too much frosting. I put a candle in it, lit it, and sang to myself, not quietly, not ironically, but like someone arriving to a party she threw and meant to enjoy. The woman at the next table, a stranger with paint on her knuckles, started singing too. When the candle sputtered out, we applauded without embarrassment. I cut the slice in half, slid a plate her way, and she said, “Happy birthday, whenever it is.” I took a bite and realized there was no longer a day they could forget that I could not remember for myself.

The hospital called to confirm an appointment and asked if my “family member” could bring me. “Friend,” I corrected, and gave Marissa’s name again, the syllables both sturdy and light. On the way there, she reached for the radio and then paused. “Music or quiet?”

“Quiet,” I said. “I have a letter writing in my head.”

“Good,” she said. “Letters are doorways.”

At the check-in desk, the receptionist smiled at Marissa and then at me, and for the first time in a long time I realized that the world saw me—and the person next to me—as something complete, with or without the people who made me.

When we returned to her apartment that evening, I found a padded envelope on the doormat. The handwriting was my mother’s. I held it a long time, feeling the shape of its contents through the paper: a thick letter, maybe two. Marissa looked at my face and didn’t speak. I carried it to the table, set it down, and made tea. We sat. Alabaster leapt into my lap. I picked up the envelope again, ran a finger under the flap, and then stopped. I slid it into the drawer, closed the drawer, and exhaled. “Not today,” I said.

Marissa clinked her mug gently against mine. “Not today,” she echoed.

Part III

The season turned, as seasons insist on doing. I went back to work part-time, slowly reentering the orbit of my desk plant and coffee mug and the soft arguments of my billing software. People were kind in the way that can sometimes feel like surveillance, but my manager—who had brought me the cardigan—treated me like a person first and a patient second. She asked if I wanted to ease back into the trickier accounts and gave me the option to say no. The power of that option changed everything. I said yes.

On a Wednesday afternoon, the office break room hummed with microwaves and small talk. I heated leftover soup and stared out at the parking lot, where a man in a bright vest pushed a cart of supplies and whistled a tune no one could place. Allison from HR joined me, breaking a granola bar in half without asking whether I wanted any. She handed me the bigger piece. “How are you?” she asked.

“Better,” I said.

“You look taller,” she said, and we laughed because it was absurd and true.

I changed my will, a document I hadn’t thought about since a cheap online template filled in “Mother” and “Father” with the certainty of software. I removed them, added Marissa, added the college friend who had driven three hours, added the neighbor who’d brought a book and later watered my plants without being asked. It felt like rearranging furniture in a room that finally fit.

On a Sunday, I went to a support group called Boundaries Are Bridges, which sounded like something I would have mocked in another life. We sat in a circle of metal chairs that complained when people shifted. The facilitator—gray hair in a loose bun, sweater with exactly one thread pulled loose—invited us to say why we were there in one sentence. When my turn came, I surprised myself by speaking without shaking. “I’m here because my parents chose dinner over me,” I said. “And I chose a letter over them.”

No one gasped. No one offered an apology on behalf of the universe. A man across from me with a tattoo of a lighthouse on his forearm nodded as if I’d given him the answer to a riddle. After the meeting, he held the door for me and said, “Letters are anchors.” I smiled. “And scissors,” I added.

Back at Marissa’s, the envelope in the drawer became a kind of weather system—sometimes I forgot it; sometimes I sensed it like thunder in the distance. On a day when the city smelled like hot pavement and cut grass, I opened the drawer and took it out again. I walked to the recycling bin and stood a long time, holding both possibilities: to read and reopen, to discard and declare an ending. I couldn’t do either. I placed it back in the drawer and told myself that indecision can be a form of kindness when it’s directed at the self.

My brother texted a picture of him and Becca at a vineyard—rows of green and a smile so white it looked computerized. He wrote, You would like her. She’s down-to-earth. I typed and erased three versions of no. Then I put the phone on airplane mode and went for a walk. The evening light made strangers’ windows look like framed warmth. I passed a family eating dinner on their porch; the father told a joke so bad the children screamed with delight. For a moment, I ached—not for my past, but for a version of it that never existed. I allowed the ache and let it go when it was ready.

I added small rituals to my days: lighting a candle before bed; placing a hand over my heart when I woke up, just to confirm that it was still mine; buying flowers for no reason. I wrote postcards to myself, mailed them from different neighborhoods, and smiled when they arrived a day later, proof that even when you send love to the wrong address, it can still find you.

The hospital called with the results of a final scan—no new anomalies, no surprises. “You’re clear,” the doctor said. I thanked him and hung up and then found myself on the floor of the kitchen, laughing through tears. Marissa sat beside me without fuss, back against the cabinet, knees drawn up like we were teenagers. “Clear,” she repeated, softly, as if reading a weather forecast. “Clear is a beautiful word.”

We made a list that night of things that meant clear: windows after rain; a slate wiped clean; a conscience that finally believes itself. We added: a bed made in a hospital room with a letter on it. We added: a door that opens and doesn’t fear who is on the other side.

A week later, my parents’ number appeared on my phone while I was at the grocery store, comparing prices of oranges as if thrift could save me from decisions. I watched it ring. I let it stop. It rang again. I answered.

“Hello,” I said, voice neutral.

“Thank God,” my mother said. “You picked up.”

I said nothing.

“We came to the hospital,” she added quickly, accusation disguised as proof. “We were there.”

“At midnight,” I said. “You stood in the hallway and left.”

Silence. Then my father, voice tightened. “We didn’t want to wake you.”

“You were already eating,” I said, and surprised myself with how even it came out. “You were at dinner.”

“We were with your brother,” Mom said, as if that explained everything.

“I know,” I said. “You told the nurse.”

“You left a letter,” she continued, and the way she said letter made it sound like weapon, like witchcraft. “You think words are enough to end this?”

“Words are all you ever gave me,” I said. “Prayer instead of presence. Advice instead of apology.”

“We are your parents,” Dad said, stiff with a kind of authority that dissolves at adulthood’s edge.

“I am not your rescue plan,” I replied. “Not your accountant. Not your scapegoat. I’m your daughter, and I am choosing not to be hurt by you anymore.”

“We raised you,” Mom said, as if saying it summoned evidence.

“You grew me,” I said. “Other people raised me. Teachers who stayed late. Friends’ mothers who remembered my birthday. The librarian who let me hide in the stacks until the library closed. The nurse who held my wrist and called you when I couldn’t. You chose dinner.”

No one breathed for a moment. Then: “We’re praying for you,” my father said, and I almost laughed.

“Pray if you must,” I said. “But pray for yourselves. You’ll need it.”

I hung up. My hands shook in the produce aisle, so I steadied them on a pyramid of oranges and thought how much effort it takes to build a structure that looks natural. A child in a cart reached for the fruit, and her mother laughed as one rolled away, and the world kept being itself without my family deciding what that meant.

That night, I took the envelope from the drawer and held it to my chest. “You don’t get to make me small,” I told it, as if it could hear. I slid it into the fireplace and struck a match. The paper curled and blackened, the handwriting disappearing into a soft dark. I watched until it was ash, then opened the damper to let the smoke go where I couldn’t follow.

Part IV

I moved into a new apartment with windows that faced east so I could watch the morning stitch itself to the world. The first night, I lay on the floor and listened to the upstairs neighbor’s footsteps and decided it sounded like company rather than intrusion. I painted one wall the color of wet clay and hung a frame with no picture in it. The empty frame reminded me that not everything needs to be filled to be beautiful.

I sent a final letter, not to my parents, but to myself, dated one year in the future: You kept the door closed and found a garden behind it. Keep watering. Keep weeding. Keep the gate. I sealed it and tucked it inside a cookbook Marissa had given me. Between recipes for soup and bread, a promise waited.

The holidays came and, for the first time, did not feel like tests. Friends gathered at my small table and spilled onto the floor when chairs ran out. We burned the rolls and called it rustic. We went around naming what we were grateful for and I said, “Silence that doesn’t hurt,” and everyone understood. We clinked mismatched glasses, and later we stood in the cold on the balcony wrapped in blankets, watching our breath drift upward. The lights across the way blinked on and off, and I felt both rooted and expansive, a tree that had survived a storm and discovered it had grown.

My brother sent a photo of a ring on Becca’s hand. No message. Just the image, like a postcard from a country that didn’t have a name for me. I didn’t reply. I did not hate him; I simply wasn’t accepting invitations to a theater that had always cast me as the understudy to a role I never wanted.

Months passed. I learned the names of the barista and the night janitor in my building and the woman who walked a dog named Mr. Darcy in a little coat. I sent birthday texts to people I’d once been too tired to remember, and in return I received a cascade of small, sincere fragments of other people’s lives. Presence multiplied itself. My phone became not a battleground but a doorbell.

On a Sunday morning, I visited the hospital with a tin of cookies and a card addressed to the ICU nurses. The unit smelled the same—antiseptic and lemon, a scent that used to mean fear and now meant endurance. A nurse I didn’t recognize took the tin, read the card, and smiled hard enough that her eyes went as bright as the monitors. “People don’t usually come back with cookies,” she said.

“I didn’t know how else to say it,” I told her. “Thank you for treating me like I mattered when the people who should have didn’t.”

“You did matter,” she said. “You do.”

I stepped outside and sat on the bench where families text each other wild rumors and half-truths. The sky was a careful blue. I thought about the line the nurse had delivered with no ceremony: You do. There is a generosity to the present tense that the past can’t manage.

On my first spring in the new place, I planted herbs in mismatched pots: basil and mint and a rosemary that tried to be a tree. In the evenings, I pinched leaves and let the scent remind me that living is full of good inconveniences—plants that need water, dishes that need washing, people who need you to show up and then let them leave when they must. Marissa came over and we cooked the way we’d done for months—inefficiently, joyfully, smudging recipes with our fingers. At the table, we made a new ritual: toasting to the thing that had most surprised us that week. She said, “That I enjoy being alone.” I said, “That I can say no and the roof doesn’t fall in.”

On the anniversary of the night in the ICU, I wrote another letter, short and clean:

You stayed.

You chose yourself when you were the one falling.

You learned that survival is not waiting for rescue; it is naming what you will no longer endure.

You left a letter and took your life.

I folded it, sealed it, and slid it into the frame with no picture. The frame leaned against the wet-clay wall as if to say, Here, this belongs. I invited a few friends over that evening. We ordered too much takeout and ate it picnic-style on the floor. We told stories about the worst advice we’d ever received and the best meal we’d ever had. I realized, somewhere between laughter and the last bite of cold dumpling, that I had built a life that would have been unrecognizable to the version of me who learned to put other people’s forks away before she tasted her own food.

Late, after the dishes were stacked and the lights had dulled, I stood alone at the window. The city made its soft noise. Somewhere, perhaps, my parents sat at a table, reading a menu like a map. I did not wish them harm. I wished them insight they might never find, peace they might never earn. But I did not wish them here.

My phone lit up with a message from an unknown number: We’re thinking of you. I stared at it, recognizing my father’s cadence cloaked in a stranger’s digits. I put the phone face down. The apartment held its breath with me, and then we both exhaled. I turned off the lamp and walked to bed, the floor cool under my feet, the night gentle.

In the morning, the east-facing windows caught the light and threw it into the room like a promise. I made coffee and stood in the sun, eyes closed, counting my breath. One for the nurse who pressed my wrist and told me to stay. Two for the friend who waited outside the hospital doors. Three for the neighbor with the book. Four for the manager with the cardigan. Five for the cat who slept on my pillow. Six for the therapist who asked me to name what I wanted. Seven for the version of me who wrote a letter and left it on a bed. Eight for the woman who walked out into the cool air and did not look back.

Nine for the empty frame that is not empty anymore.

Ten for the silence I chose, which is no longer the silence they gave me.

People sometimes ask if I forgave them. I don’t know how to answer that in a way that fits in other people’s mouths. Forgiveness, to me, would require acknowledgement and repair, and they sent neither. What I did was refuse to drink from a poisoned well, even when I was thirsty. I chose better water. I chose to let the drought end without them.

If there is a moral, it is smaller than revenge and bigger than grief: love is presence. It is the hand on the wrist, the drive in the rain, the seat kept warm. It is showing up without being asked and leaving when asked the first time. It is remembering the date even when the world is loud.

The story doesn’t end with a door slamming or fireworks in the sky. It ends with my kitchen window open and rosemary in the sink and a text from Marissa that says, Soup tonight? It ends with me replying, Yes. It ends with two bowls on the table and steam rising and laughter that needs no audience.

And it ends with a bed in a hospital, empty and neatly made, a single letter laid in the center like a compass pointing away from everything that hurt, toward a life I dared to recognize as mine.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

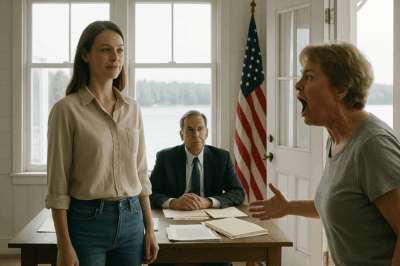

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

CH2. “Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp

“Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp Part I — The…

CH2. Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL.

Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL …

End of content

No more pages to load