My Parents Chose a Wedding Over My Dying Son — I’ll Never Forgive Them. When my seven-year-old son needed $85,000 to survive, my parents said it was “too much.” Weeks later, they spent nearly triple that amount on my sister’s dream wedding.

Part 1

You ever learn the exact price of hope? It fits in a box on a payment screen. It blinks. It waits. Eighty-five thousand dollars. The number looked like a dare, like the kind of math you stare at so long your eyes stop believing in numbers at all. I wrote it on a sticky note and pressed it to the refrigerator because I wanted the house to know the truth with me.

Noah’s oxygen machine filled the apartment with a sound like the ocean through a cracked shell—constant, private, a hush that made everything else feel too loud. He slept with his mouth open, one hand caught in the plush ear of the stuffed dog he’d named Captain. The machine pulsed; Captain watched; I counted seconds between shallow breaths like someone trying to memorize the ticks of a bomb.

“Mommy?” he’d say when he woke. Just that. No complaint, never that. He’d blink like mornings were something he could still afford.

I’m Rachel. Thirty-one. I teach eighth-grade English and can break up a hallway fight with only my eyebrows. I grade essays with a green pen because red feels like a siren. I became a mother at twenty-four and a statistic at twenty-six. The statistic had a good smile and a motorcycle and a talent for quiet exits. Noah and I learned to be small and brave together.

When the cardiologist explained the new treatment—a program the insurance company called “exploratory,” which is code for “your problem”—I nodded like I knew how anyone survives a number like that. A shot at longer. A shot at running without turning purple. A shot at time, which is the only currency that matters when the people you love are busy losing it.

“We can’t make promises,” the doctor said, because doctors are allergic to nouns they can’t measure.

“Can you make an invoice?” I asked, because I can’t stop trying to solve the problem in front of me with the tools I have. This is what teaching does to your brain.

He gave me a folder. The folder weighed nothing and everything. Eighty-five thousand dollars. Due before the first session; the hospital liked their miracles prepaid.

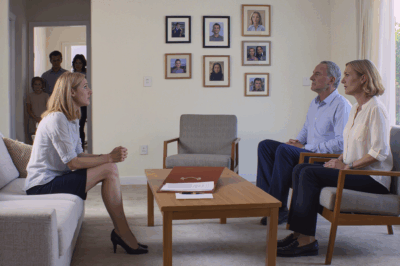

I called my parents because I still believed family meant net, meant catch, meant someone else’s hands keeping you from hitting the floor. They came over in their good coats like they were on their way to a matinee. My mother stood with her purse hooked to her forearm. My father didn’t sit. They looked at my apartment the way people look at rentals in a neighborhood they don’t intend to move to.

I explained the treatment. I showed them the binder. I used the voice I use at school when I need the room to understand something serious without panicking. I left out the worst words. I left in the price.

“We don’t have that kind of money lying around,” my father said, like I’d asked him to check the couch cushions. “You need to be realistic.”

Realistic. The oxygen machine clicked. Noah shifted in his sleep, but didn’t wake. I had the wild urge to clap so they’d startle and feel what I felt every second of every day: the cruel physics of watching someone you love breathe like it’s an assignment they might fail.

“I’ll pay you back,” I said, and I meant it, less because it was possible and more because I needed them to know I wasn’t opening my hands for charity. I was offering a bargain: money now for the privilege of helping a little boy learn how to be eight.

“We already helped,” my mother said, eyes wandering to the plant that was not thriving on the windowsill. “Three surgeries. Years of… of support.” She didn’t like the word “money.” It stuck to her teeth. “We have to think about retirement.”

“Retirement,” I repeated, in a voice I didn’t recognize. It sounded like someone discovering a new use for an old word. Retirement—the life you plan to live when time is plentiful. My son’s time was not plentiful. My son’s time was a jar with the lid off.

They left with the same careful politeness they’d brought. The door closed in that soft way doors close when the world is about to change and doesn’t want to wake anyone. I sat on the edge of Noah’s bed and watched the small rise and fall of his chest and tried to teach my body how to still feel like a home for him.

That night I started calling. Cousins I hadn’t seen since they taught me to do the Electric Slide at a family reunion. Co-workers who’d pressed coffee into my hand on parent-teacher conference nights like it counted as a form of prayer. People from high school whose last names I hadn’t had to say out loud in a decade. I made a fundraiser page on the internet and wrote the story with every ounce of honesty I could afford. I posted photos: Noah in a dinosaur shirt, Noah with frosting on his cheek, Noah curled around Captain like a comma.

Two weeks later, I had twelve thousand dollars. People who had no reason to care cared. Strangers sent twenty dollars with notes that made my private heart bow. Twelve thousand was hope’s loose change. It wasn’t time.

On the afternoon I learned that kindness sometimes loses to calendars, my sister Grace called with a squeal so high it clipped the audio on my phone. “Ethan proposed!” she cried. “He rented the rooftop at the hotel with the string lights, you know, the one with the swan wall? And Mom and Dad said they’ll pay for everything. No budget limits. Can you believe it?”

No budget limits. I looked at the spreadsheet where I had subtracted donations from a number that did not budge. I looked at the oxygen machine’s soft green light and wondered if it could throw a wedding.

From that day forward, the group chat turned into a carnival. Venues. Menus. Florists. Decisions floated past me like parade balloons I couldn’t afford to touch. My mother’s texts arrived in clusters: peonies vs. ranunculus, a photographer whose Instagram gave you allergies from all the perfect. They used the words “dream” and “timeless” and “statement piece.” I learned the cost of a bachelorette weekend in Napa. It was a month of treatment. I couldn’t stop doing the math.

I sold my car and learned to carry groceries in soft fists on the bus. I sold my grandmother’s ring, the one she promised I could choose my life with, and told myself rings are circles and circles mean the same thing whether they’re metal or belief. I dropped our internet plan down to just enough for the fundraiser and school. I started sleeping on the couch so Noah could have the bedroom because the sound of his breathing—the measured defiance of it—made me braver.

By summer he was too weak to walk. He learned to measure courage in chairs. I learned to measure days by the distance between doses. When I called my mother to tell her the doctor had said “months, maybe less,” she sighed like someone hearing about rain on a picnic. “Rachel, you need to find balance,” she said, as if the word were a rope ladder I could climb to safety. “You’re letting this consume you. Grace deserves her moment, too.”

Her moment. My son was running out of moments.

Part 2

Noah loved books about trains and books about foxes who didn’t ask permission. He loved the blue cup more than the yellow cup. He loved when we pretended the oxygen machine was a whale sleeping in our living room. He asked questions like a scientist and like a seven-year-old combined, which is to say the questions were pure and lethal. “Why do hearts get tired?” “Why do people say forever and mean Saturday?”

We moved to palliative care on a Wednesday that didn’t have the decency to rain. The hospital room tried very hard to pretend it wasn’t a hospital. A mural of clouds floated above the bed. The nurses wore sneakers with bright soles like exclamation points. The oxygen machine in this room was a cousin of ours: same hum, new tone. The palliative doctor spoke with the calm of a person whose job was not to save us from what was coming but to make sure we weren’t alone when it arrived.

I read to Noah every night until my voice felt like a sweater I was stretching out of shape. He never complained, not once, not when the IV tape pulled tiny hairs, not when the blood draws bruised, not when the world divided itself into beeping and waiting. He’d say, “More, please,” and I’d turn a page, and it felt like buying time with verbs.

The wedding juggernaut picked up speed. Grace sent me photos of dresses that looked like clouds that had gotten ideas. My mother asked my opinion on chargers. I learned that a charger is not a device but a plate you put under a plate when the first plate is not enough. I learned the cost of a charger. I learned the cost of two hundred chargers. I learned it again at three in the morning when the machine changed its sound and Noah stirred and I stroked his hair until the sound softened.

I asked my parents again. I asked like someone who still believed language could rearrange choices. My father said they had already given. My mother said she was exhausted. “Everything is heavy with you, Rachel,” she said, like I was an anvil she had accidentally stored in her purse. “You have to let Grace have some joy.”

They spent ten thousand dollars on a bachelorette weekend in Napa. I saw the photos on my phone between refilling the humidifier and writing a sub plan. Grace in a sash that said Bride. Wine flights. A sunset that looked expensive. I didn’t begrudge her happiness; that’s what they don’t tell you about grief. It makes you bigger and smaller at once. I wanted my sister to laugh. I just wanted my son to live long enough to learn the punchline to his own jokes.

At school, my students learned to hand me tissues without looking at me. They wrote essays about symbolism like their lives depended on it and sometimes, in a classroom, they do. The principal stopped me in the hall and said the staff wanted to donate their sick days. “Take the time,” she said, and because I am an adult who has learned that accepting help is a form of doing your job well, I took it.

The fundraiser crossed $20,000 with a note from a man in Oklahoma who said his wife had been a Noah once and survived. He attached a picture: a family in a backyard, a cake on a table, the kind of ordinary that glows. Comments stacked like prayers from people who don’t pray. I printed them and hung them on the side of the cabinet above the sink so I could read one every time I reached for a glass and remember that strangers were willing to be family when family wasn’t.

On the day the doctor said “days, maybe hours,” I called my parents because even when you have learned better, you give people one last chance to be who you need. “It’s happening,” I said. “If you want to say goodbye, you should come now.”

“Oh no,” my father said. “That’s terrible timing. The rehearsal dinner’s tomorrow.”

“Terrible timing,” I said, to the air between us, like maybe the air could fix it.

They came the next morning for fifteen minutes. They brought Starbucks. My father checked his watch twice. My mother said the florist was “a nightmare” in a tone that made me want to laugh and then set something on fire. They stood near the foot of the bed like tourists in a museum, quiet, interested, unmoved. Noah was sleeping. They left a cake pop on the tray table. I threw it away after they were gone because food belongs to the living.

Noah died three days later. He went so gently it felt like he was apologizing for the inconvenience. I held him and told him the story where the fox wins and Captain sleeps and hearts never get tired. The room went suddenly, savagely quiet. The machine hummed for a few seconds as if confused and then stopped.

When I called my mother, she whispered, “Oh, Rachel, not now. The wedding’s in two days.”

Something inside me broke without sound. Not a crack, not a shatter—just a shape shifting. Silence can be an instrument. This one tuned me to a new key.

They asked me to move the funeral. “Friday doesn’t work,” my father said. “Too close to the rehearsal dinner.” They wanted Thursday. I told the funeral home Friday. I told my parents Friday. I didn’t change a thing.

They arrived late. They left early. They made it to the wedding on time.

Part 3

Grief is a room with no windows and excellent acoustics. Everything you say to yourself comes back louder. The second morning after the funeral, I woke to a quiet so entire I thought I had gone deaf in my sleep. Then I realized what was missing: the machine. Silence had a different weight now. I sat on the floor with my back against the couch and pressed Captain to my chest and said Noah’s name until it felt familiar in the air again.

People brought casseroles and tried to make me eat. My students sent a card they’d made with a drawing of a fox wearing a graduation cap. The landlord slipped a note under the door: “Take your time with the rent this month.” The internet kept sending money; grief is strangely good for algorithms. I stopped counting. The number no longer mattered.

Grace called two days after the wedding because that was the length of time her happiness took to make room for the word sister. “The photos are… incredible,” she said, like the word was alive. “The venue did sparklers at the end, and our hashtag trended for, like, a minute.” She took a breath that sounded like she was choosing, then said, small, “I’m sorry about Noah.”

“Thanks,” I said, because I am a person who can write a thank-you note in a hurricane and mean it.

“You should come over,” she said. “Mom says it would be good for you to be around family.”

“I think I’m done with that,” I said, not cruel, just precise.

She was quiet long enough for me to know I had hit something true. “They paid for everything,” she said suddenly, a confession smuggled into a conversation about nothing. “I didn’t know how much. I didn’t ask. I… I’m not asking you to forgive them. I’m just asking you not to disappear.”

I wanted to tell her I had spent months learning how to disappear loudly. Instead, I said, “Tell me something that wasn’t perfect.”

“The cake collapsed in the kitchen before they brought it out,” she said, relief flooding her voice at the invitation to be human. “They had to rebuild it with frosting and prayer.”

“Good,” I said. “I hope it tasted like effort.”

After we hung up, I wrote a letter to my parents I did not send. It was short. It said: You chose a wedding over a life. I will never forgive you. I will never call you. If you ever want to see me, the cost is a number you do not have.

Then I did what grief sometimes requires: something ordinary. I scrubbed the tub. I took out the trash. I washed Noah’s sheets with the expensive detergent he loved because it smelled like a fruit he’d once tried and declared “too fancy.” I folded the sheets and put them back on his bed because it felt like a promise to the piece of my heart that might one day want to sleep there again, or to the next child who needed a room to learn the shape of morning.

A week later, the hospital called about the fundraiser balance. “We can return it,” the woman said gently, “or you can designate it for family assistance funds.”

“Family assistance,” I said, the words a corridor my body walked down before my brain caught up. “But I want to be the one who decides. I want to know their names.”

“You can’t pick individuals,” she said, apologetic. “We can tell you stories. We can send updates.”

“Stories,” I said. “Yes. Send me stories.”

They did. A baby who needed a medicine that tasted like tin and hope. A teenage girl whose heart was hurrying itself into trouble. A father who watched a bill grow like mold. I learned to read medical narratives the way I read essays—looking for the shape beneath the words, the argument the writer didn’t know they were making. When the first update arrived saying a toddler in a red sweater had cleared a hurdle because the fund covered a cost, I printed the email and taped it next to the fundraiser comments. The cabinet door became a small gallery of borrowed mornings.

People asked about my parents like we were talking about weather. “Have they reached out?” “Will you ever talk to them again?” I started answering honestly. “They texted a photo of the wedding program.” “No.” The word felt like a complete sentence for the first time in my life.

I found a therapist who didn’t use phrases like “finding peace” and instead said, “How are you keeping your promises to yourself this week?” We sat in a small room with a fake fern and made lists. I wrote: sleep. walk. eat green food. do not answer calls in which the first word is “but.” She asked me what I wanted the rest of my life to be about, and the answer arrived as if it had been waiting under a pile of laundry: I wanted to make sure no one else had to stand in a kitchen with a sticky note on the fridge and choose between a person and a party.

So I made a new fundraiser page. Not glossy. Not tragic. Simple. I called it Noah’s Pocket because kids put everything they love in their pockets and because a pocket is where you keep emergency money and because saying his name in public felt like stitching him into the world where he belonged. I wrote: We help families pay for the part of care that makes insurance nervous. We help quickly. We ask gently. We don’t post photos without permission. We don’t make grief perform.

The first month we raised two thousand dollars. The second month, a woman in Nebraska sent a check for $15 with a note that read, “For a mom who is doing math at midnight.” I cried in the post office line and the clerk handed me a tissue like he’d been waiting for that scene all day.

Part 4

In September, I returned to school. The hallways smelled like pencil shavings and hope. On the first day, a kid named Marcus asked if the fox in our class novel was “a metaphor for capitalism,” and I decided I loved eighth grade again. I kept a photo of Noah in a thin frame on my desk, tucked behind the pen cup, visible only if you were looking for it. Some kids saw it and said, careful, “Is that your son?” I said yes. If they asked what happened, I said, careful, “He had a heart that worked too hard for too long.” They nodded like people who had seen adults cry in kitchens and understood more than was good for them.

At home, the apartment learned to be an apartment again. The oxygen machine went back to the medical supply store. The corner where it had sat looked like a museum exhibit of absence. I moved the bookcase into that space and filled it with things that made noise: paperbacks, board games, the shoes Noah had wanted so badly and worn twice. My friend Lila helped me paint the wall. We picked a blue so deep it felt like standing in a lake at night. When the paint dried, I ran my palm over the smoothness like it could teach my skin how to keep healing.

Grace texted sometimes. Photos of her new apartment. A selfie with Ethan in front of a food truck that sold tacos too delicious to be legal. She asked about Noah’s Pocket. I sent her the link but not the numbers. She wanted to meet. I didn’t. “Not yet,” I wrote. “Maybe next month. Maybe next year.”

In October, my parents mailed a note in my mother’s handwriting, full of loops I used to emulate when I was trying to be her. “We didn’t know how to help,” it said. “We love you.” There was a check inside for $1,000. I left it on the counter for a week. Then I endorsed it to the hospital’s family assistance fund and wrote on the memo line: For the child who needs help now.

They called. They texted. They used the words “misunderstanding” and “hurtful” and “unfair.” I blocked their numbers and then unblocked them because I didn’t want to spend my life wrestling with the technology of refusal. I changed nothing else. They stopped for a while. They started again after Christmas with a photo of a tree lit like a jewelry case. I deleted it without opening.

Noah’s Pocket grew in fits and starts, like a child. We helped with gas cards and plane tickets and the kind of grocery trip that lets you stop making tradeoffs. We helped cover the part of a pharmacy bill that made a proud father cry in a parking lot. We paid for someone’s lost wages and someone else’s babysitter. We did not make anyone beg. I sent notes to donors with details as small and safe as I could: a mother in Toledo heard her child laugh during a blood draw because she did not have to worry about rent this month. A girl in Phoenix ran three steps farther. A boy in Portland ate a popsicle on a porch that wasn’t about to be taken away.

A journalist emailed me from a local paper. “Could we do a story?” she asked. “People should know.” I said yes, then no, then yes again. She asked about my parents. I said, “The story isn’t about them.” She wrote the piece anyway. The headline was ordinary. The photo was me at my kitchen table with Captain on the chair beside me, which made me text the photographer a thank-you that included too many exclamation points. The article went minor-viral in the meaningful way. Donations ticked up. A woman whose brother owns a printing company offered free brochures I didn’t want but accepted because people like paper. We made the brochures unglossy and honest. We used verbs like “cover,” “deliver,” “answer.” We used nouns like “rent,” “medicine,” “gas.”

One afternoon in late winter, I saw my father through the cafe window on my block. He was stirring a coffee like it had misbehaved. For a second I thought about walking past, and then I thought about Noah asking me one of his knife-clean questions: Why are you hiding? So I opened the door and went in and ordered tea I didn’t want and stood by the napkins like they might break the moment’s fall.

He saw me and went pale in a way that used to make me feel responsible. He came toward me with a careful smile, the one he wears when he’s about to sell someone something they didn’t ask for.

“Rachel,” he said. “You look good.”

“I look like a person who takes walks,” I said. “What do you need?”

He flinched at the word like I’d smacked him with it. “We miss you,” he said. “Your mother hasn’t slept.”

“Neither did Noah,” I said, and watched him decide not to hear it.

“Can we start over?” he asked. “Things got… heated.”

“They got accurate,” I said, because I’m done giving sentences soft landings. “You made a choice. I’m making mine.”

His eyes watered. For the first time, I believed the sadness belonged to him and not to his sense of himself as a good man. “We didn’t understand,” he said.

“You didn’t look,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

He nodded because he had run out of arguments and discovered the paddles were words he had never learned to use. “If we write a check now,” he said, desperate, “for your—what is it—Noah’s Pocket—will that help?”

“It will help someone,” I said. “It won’t help this.”

He stood there with his hands empty and his mouth doing math that finally didn’t add up to the answer he wanted. “We love you,” he said.

“Love is not currency,” I said. “I keep the books.”

I walked out with my tea. It tasted like water that had a memory of leaves. I poured it into a planter on the sidewalk and watched the dirt go dark in a shape that would evaporate before I got home. I felt sad for the girl who had spent years believing the right combination of words could turn two people into parents. I felt free of her, too.

Part 5

The first spring without Noah smelled like wet sidewalks and barbecue smoke drifting in from someone else’s joy. I bought a pair of running shoes and discovered that you can run even when you feel like a museum of broken glass. You just keep picking up your feet. Some days I ran toward nothing. Some days I ran toward the idea of a future that would be wide enough to hold the part of me that was always seven.

In May, our school held an awards night. I gave the eighth-graders certificates for “Excellence in Metaphor” and “Most Creative Use of a Semicolon.” Parents clapped. Some cried. After the ceremony, a woman with tired eyes and a red scarf approached me and introduced herself as Evan’s mom. “We were in the hospital last year,” she said. “Your fund helped with our rent when we were there for three weeks.” She held out her hand like a gift. “He’s okay.”

I wanted to lay down on the linoleum and sleep for a hundred years. “Thank you for telling me,” I said. “Tell him a teacher he doesn’t know is very proud of him.”

In June, Grace came to my door with a box. She looked smaller. She looked like someone who had discovered that weddings are not a good leash for time. I let her in because some doors will always open for the right knock.

“I’m pregnant,” she said, like a confession and a celebration braided together. “I wanted you to hear it from me.”

I felt my heart reach for her and recoil at once. “Congratulations,” I said, because joy deserves to walk in even when grief already lives there. “When are you due?”

“January,” she said, then took a breath. “I brought this.” She set the box on the table and lifted the lid. Inside, the wedding album—heavy, glossy, full of faces arranged like proof. “I don’t want it,” she said, surprising both of us with the honesty. “I don’t want to see that day next to the one I lost.”

“You didn’t lose that day,” I said. “You just learned what else it cost.”

She winced, then nodded. “Mom and Dad want to be in the baby’s life,” she said. “They think you’ll… Your refusal makes it complicated.”

“My refusal made it honest,” I said, then softened. “You get to make your own boundaries. You get to have parents even if I don’t.”

She cried then, full and ugly, and I did, too, because crying with your sister is muscle memory. We sat on the floor with Captain between us and the album watching us like a court stenographer.

“Will you be in her life?” she asked, rubbing her hands over the box top like she could warm them on it. “The baby?”

“I don’t know,” I said, telling her the truth instead of the story a nicer person might tell. “Ask me when she’s born. I might be brave by then.”

In August, Noah’s Pocket paid for a hotel room so a mother could sleep for six hours while an aunt took a shift in the hospital chair. I cleaned my apartment like a ritual. I threw away the sticky note on the fridge because I knew the number by heart and didn’t need its handwriting in my kitchen anymore. I framed a photo of Noah from the last good day, the one where he stood on a bench and yelled at the river for being too loud, and put it on the shelf at eye level so he could meet me there every morning and remind me not to whisper my life.

In October, a reporter from a national magazine called. “We want to talk about medical debt and weddings,” she said, because journalists love a metaphor that bites. I said yes because I was ready to say the quiet part out loud in a place where people who make decisions might be forced to hear it. The piece ran under a headline that made me roll my eyes and then tear up. Lawmakers tweeted. My inbox turned into a storm and then a sky. Donations doubled for a week. Then tripled. We started saying yes faster. We started saying yes before people finished explaining their reasons. I hired someone to help and paid her more than I could afford because some salaries are investments in your own ability to sleep.

The day the fund crossed $85,000 in a single month, I printed the receipt and taped it to the cabinet next to the first email about the toddler in the red sweater. I stood on a chair and looked at the wall of paper and felt like I had built a house out of strangers’ good intentions. I climbed down and made dinner and ate it at the table without looking at my phone. Small triumphs are still triumphs.

My parents sent a letter at Christmas. It said, “Please forgive us,” and it said, “We didn’t mean to hurt you,” and it said, “Family is everything.” I read it once and put it in the box with the wedding album. On New Year’s Day, I took the box to the storage unit I pay for with the part of me that still believes future-me might want things present-me can’t stand. I labeled the box with a thick black marker: History. I put it on a high shelf where I could reach it if I wanted to and couldn’t trip over it if I didn’t.

Noah’s birthday came. I took the day off. I went to the park with a bag of fox-shaped cookies and a thermos of cocoa and left the cookies on a bench with a note that said, “If you find this, it’s for you. Be kind to your mom today. Signed, a kid who loved cookies.” I sat on the swing and let it creak and told the sky the jokes he used to love and waited for a laugh I could believe belonged to him.

That night, I wrote him a letter. I told him we were helping people. I told him his stuffed dog still slept on the couch on Tuesdays because that’s where he liked to sit. I told him his room was still his room and that the bed was made with the fancy-smelling sheets and that I was still terrible at folding fitted sheets and always would be. I told him I would never forgive the people who could have helped and didn’t. I told him that not forgiving didn’t mean I was choosing hate. It meant I was choosing a different verb: build.

Here is the ending, clear and ordinary and exactly as sharp as it needs to be.

My parents chose a wedding over my dying son. They called $85,000 “too much” and then bought flowers big enough to hide in. They made a decision I will never forgive. That word is not a door I will ever open for them again. The choice lives where it belongs: between them and their mirrors.

What lives with me is this: a small boy’s laugh lodged in the paint of a room. A machine’s hush that still visits my sleep. A fund named for pockets and mornings and all the ways strangers will carry one another if you hand them a name and a number and ask nicely. A sister’s hand on mine, sticky with frosting and grief. A future that does not require me to forgive in order to move. A promise kept in a kitchen with a cabinet full of paper and a wall that knows exactly how much I’ve learned.

I’ll never forgive them. I’ll never have to. I don’t need their apology to honor my son. I don’t need their checks to buy someone else a month. I don’t need their version of love to define mine.

What I need is the work. What I need is the next family on the phone, the next small invoice that turns into time, the next mother who texts a stranger, It helped. He laughed today.

And what I have, at last, is what they would not give me: enough. Enough voice to say no. Enough yes to say to others. Enough mornings to turn on the kettle and look at the photo on the shelf and say, “Happy Wednesday, sweetheart,” like time is a thing we get to choose how to spend.

Epilogue: a small future

Grace had a daughter in January. She named her June. She sent me a photo two hours after June was born because some habits live in a bloodstream. I stared at the baby’s fingers and thought about all the hands they’d learn to hold and all the hands they’d refuse. Grace asked if I wanted to visit. I said, “I’m not ready.” Two weeks later, I was. I went to the hospital with a fox onesie and a note tucked into the bag that said, “Welcome to a world where we will make better choices.”

June’s hair smelled like the inside of a promise. I held her and cried and didn’t apologize to anyone for the mess of it. Grace and I looked at each other over the small, breathing proof that life is rude and generous at once.

I still don’t speak to my parents. Grace does. That’s her boundary. I respect it the way I want her to respect mine. We plan to take June to the park when she’s old enough to steal a cookie and run. We plan to tell her stories about a boy named Noah who loved trains and foxes and mornings. We plan to teach her that love is a verb that buys groceries and answers the phone and shows up before rehearsal dinners. We plan not to use the word “forever” lightly.

Sometimes, late at night, I still hear the hum of an oxygen machine that isn’t there. When it happens, I get up and go to the kitchen and run my fingers along the edges of the papers taped to the cabinet—numbers that turned into days for people who needed them. I stand there until the phantom hum fades and the real quiet comes back, the good quiet, the kind that belongs to a home.

Then I turn off the light, and I go back to bed, and I dream about a fox who outsmarts a trap and naps in the sun, and about a boy who runs along a river and laughs at how loud it is, and about a woman who learned the cost of hope and paid it forward, with interest, forever and ever—by which I mean as long as I have mornings to choose.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My DAD Shouted “Don’t Pretend You Matter To Us, Get Lost From Here” — I Said Just Three Words…

My DAD Shouted “Don’t Pretend You Matter To Us, Get Lost From Here” — I Said Just Three Words… …

HOA “Cops” Kept Running Over My Ranch Mailbox—So I Installed One They Never Saw Coming!

HOA “Cops” Kept Running Over My Ranch Mailbox—So I Installed One They Never Saw Coming! Part 1 On my…

I Went to Visit My Mom, but When I Saw My Fiancé’s Truck at Her Gate, and Heard What He Said Inside…

I Went to Visit My Mom, but When I Saw My Fiancé’s Truck at Her Gate, and Heard What He…

While I Was in a Coma, My Husband Whispered What He Really Thought of Me — But I Heard Every Word…

While I Was in a Coma, My Husband Whispered What He Really Thought of Me — But I Heard Every…

Shock! My Parents Called Me Over Just to Say Their Will Leaves Everything to My Siblings, Not Me!

Shock! My Parents Called Me Over Just to Say Their Will Leaves Everything to My Siblings, Not Me! Part…

At Sister’s Wedding Dad Dragged Me By Neck For Refusing To Hand Her My Savings Said Dogs Don’t Marry

At Sister’s Wedding Dad Dragged Me By Neck For Refusing To Hand Her My Savings Said Dogs Don’t Marry …

End of content

No more pages to load