My Parents Called Me a “Failure” at Dinner — The Next Day I Bought the Restaurant

Part One

I didn’t set out to make a scene.

I set out to celebrate.

Five years of quietly building an online brand in the cracks of other people’s schedules had begun to bloom into something real: twelve employees, a distribution partnership with a specialty grocer, quarter-over-quarter growth that would’ve made any investor proud—if I’d been the kind of woman who needed an investor. I was not. I built my company the way my grandmother taught me to bake honey cakes—patiently, consistently, with a hand that never stops until the dough has enough strength to hold its shape.

So I booked Cho’s Garden—the one room in Boston where I never had to audition to be loved—and I invited my family to dinner.

My father raised his glass before the tea had even steeped.

“To James,” he declared, his voice cutting through the soft hum of the restaurant. “For his promotion to regional director. You’ll run the company one day, son. A real leader—vision, instinct, courage.”

Applause. Clinking chopsticks. James beamed and bowed his head with the kind of practiced humility that knows it will never be mistaken for anything but superiority.

“And to Emma,” my father added, an afterthought draped as a courtesy, “who tries.”

Eight letters. Two words. A crown of thorns disguised as praise.

The table laughed. Not a warm ripple, but a sharp, brittle ring, the kind of sound that makes flowers shy. The whole history of being our Emma—too soft, too earnest, too impractical—crystallized in a single toast.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t plead. I set my napkin down and stood. Through the veil of heat and shock I saw Mr. Cho watching from the corner, his hands folded, his mouth a line. When I met his eyes, he gave the smallest nod. We had spoken last week under the lanterns when I delivered lemon bars and a question: “If you’re really retiring, what happens next?”

His answer lived on the real paper, in real ink, in the folder in my bag.

I excused myself from the table with a voice that didn’t shake and stepped out into the October night.

Outside, the city carried on—curbside chatter, a siren far away, the comfort of strangers minding their own joy. I called Mr. Cho. Twenty minutes later, at a corner table, he slid a set of keys across the wood and we signed a preliminary agreement. He wanted his life’s work to go to someone who knew the menu by heart and the staff by name; I wanted to raise something without asking my father to bless it first. We signed; he wiped his eyes; I paid the deposit out of an account my family didn’t know existed.

When I returned to the table, their laughter resumed around the story James told about a “unique” digital strategy he’d pitched—a strategy I recognized because I’d given it to him two weeks ago when he called “for advice.” My mother dabbed her eyes, overcome with pride, and squeezed my hand like I had been invited to hold the scene steady for them.

I let them finish their glory.

Then I stood, tapped my water glass with the stem of my fork, and took the microphone from my father’s stunned hand.

“Since we’re celebrating work,” I said, “I’d like to thank the place that let me do mine when home never did.”

Mr. Cho stepped out of the kitchen in his street clothes. People turned. Some clapped on instinct. Others looked confused. My father frowned, irritated that a night scripted for him had stumbled into improvisation.

“Mr. Cho,” I said, “thank you for every almond cookie you gave me when I was ten and told you I wanted to be more than a prop in someone else’s story. Thank you for posting my report cards on the corkboard. And thank you for this—”

I held up the keys.

A soundless beat, as if the room had inhaled and forgotten how to exhale.

“Tomorrow morning,” I said, “this restaurant’s deeds change hands. From Cho to Phoenix.”

I didn’t need to look to know my father’s face had relocated every color on the spectrum to places colors should not go. My mother’s mouth opened and closed without catching words. James clutched his napkin like it could become a flag he could wave to own the room again.

I kept going, because this was not about their feelings; this was about tending to my own.

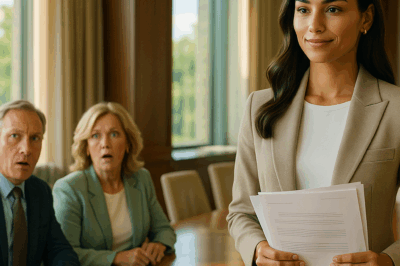

“This is not a stunt and it’s not revenge,” I said. “It’s a transfer of stewardship. Mr. Cho asked for someone who loves this room enough to keep its soul intact. He chose me. We signed this afternoon. The staff knows. The bank knows. The lawyer sitting over there,”—I gestured to the woman in a gray suit who raised her hand politely—“certainly knows.”

A murmur broke, rolled, rose. In the corner, a group of regulars—couples who had toasted anniversaries under these lanterns, a man with a cane who’d had his first date here in 1974—started clapping. The sound thickened and spread and filled the room until even the stubborn corners softened.

My father stepped forward, palm up, the universal sign of a man who thinks he can still take the mic back.

“Emma,” he said. “Enough.”

“For once,” I replied gently, “I agree.”

I gave the mic to the host and sat down. Servers arrived with plates. Tea steamed. Life resumed. Only everything had shifted by one degree, and that was enough to change a horizon.

It would be easy to tell you the story ends there—with a triumphant purchase, a new sign on the door, a photo of me and Mr. Cho under the lanterns, my father stuck in a silence he couldn’t leverage.

But restaurants, like families, are more complicated than that.

The next morning, I met the staff at nine a.m. in the back room. Hyejin stirred coffee and quietly watched me over the rim. Marco leaned against the walk-in with his arms crossed, wary and loyal at the same time. Teresa, who had carried dumplings and secrets on the same trays for thirty years, squeezed my hand once, hard.

“We won’t change what isn’t broken,” I said. “We will raise wages, add health insurance, and fix the oven that makes a clicking sound like it’s counting down to an explosion. We’ll keep the dumplings that taste like memory. We’ll take card payments without the machine crying. And we’ll create a scholarship in Mr. Cho’s name for first-generation kids who choose either kitchens or classrooms, because both change the world.”

Hyejin set her cup down. “We keep almond cookies?”

“Two per child,” I said. “Three if they have a report card.”

They laughed. Nervous. Grateful. A little stunned. I understood. You can’t throw money at a trauma and expect it to stop remembering.

By noon, two vendors called to congratulate me. By three, an inspector showed up unannounced with a clipboard and a smirk that said someone had made a phone call with a grudge. He went straight for the one broken tile behind the prep sink and tutted like he was warming up to sing.

“Good catch,” I said, handing him the maintenance order I had already printed that morning. “It’s scheduled for 10 a.m. tomorrow. You’re welcome to come back and see it fixed. I’ll have almond cookies ready.”

He blinked, deflated. “I… uh… sure.”

At five, my father texted: Cease and desist. He cc’d three lawyers and my brother. I forwarded the message to my lawyer with the subject line: Popcorn? Then I turned the sign to OPEN.

Dinner service was packed. News travels faster than good dumplings. People flooded in with flowers and curiosity and sometimes both. We comps’d nothing and offered everything—the first rule Cho taught me. You can say no to discounts and still be generous, if you learn the language of dignity.

At nine-thirty, mid-bite of my first meal as an owner that wasn’t a staff meal scarfed standing up, my brother walked in, all cologne and contrition.

“You made your point,” he said by the host stand. “Impressive. Now hand it over. Dad will make it part of the hospitality portfolio. We’ll pay you out. It’ll be safer with us.”

“With you,” I repeated. “Like my pitch deck was safer with you?”

He winced a millimeter. “Business is business, Em. Don’t take it personally.”

I gestured to the room. “This is personal. That’s what you never got. And since we’re doing math—” I pulled a sheet from the drawer. “—this is the bill for the intellectual property your firm used in your ‘unique multi-layered digital strategy.’ Itemized. Dated. With your emoji reactions on each phase.”

He laughed a sound that didn’t find humor. “You wouldn’t.”

“You already did,” I said. “I’m just invoicing.”

“Dad’s going to bury you,” he said softly.

“Then he’ll have to learn to dig,” I replied, and smiled the kind of smile you can only grow in a kitchen that has taught you how to withstand heat.

He walked out with a face like a door slammed badly—closed but still rattling.

That night, after we counted cash and loaded the dishwasher and swept the last sesame seed from the floorboards older than my parents’ marriage, I sat at the bar and wrote checks. Hazard pay for Marco for fixing the oven before it became a story on the evening news. A retainer for a benefits broker. The first draft of the scholarship flyer. It felt like laying bricks in the dark and knowing a house would be standing by morning even if nobody clapped while it rose.

Mr. Cho called at ten-thirty. “How did it go?”

“I didn’t burn it down,” I said. “And a teenage busser told me I’m scary. I take both as compliments.”

He laughed. “You were always brave. You learned to be kind to yourself.”

Kindness to myself did not extend to my father.

On day three, his attorney served a restraining order request claiming I had manipulated a “vulnerable senior” into selling a family asset. Mr. Cho, who has more spine in his pinky than my father has in his whole boardroom, signed an affidavit that read like a love letter to agency: I chose her.

On day five, a columnist who had been eating free at executives’ tables for years called to ask for “my side” of the “family drama.” I told her the menu is the side. She said that wasn’t a quote. I told her to come back when she wanted to write about small businesses that treat their staff like human beings and their landlords like partners.

On day seven, a florist dropped off a huge arrangement of white lilies from my mother—the floral language of funerals and “we are above this.” I repurposed it into three smaller vases and sent them to the ICU down the street with a note: From neighbors who know that surviving is worth marking.

The part of me that used to wonder if love meant letting people reduce me did not die easily. It flickered sometimes, like the pilot light under the tea urn. It sputtered when a family of six walked out because they had “always had table six” and didn’t like that the owner “had opinions.” It hissed when James posted a story from a competitor’s dining room with a caption about “real restaurants run by real business people.”

That part of me used to throw itself between my father’s mood and the day like a shield. Now it stayed in the kitchen and learned how to make stock out of bones.

Part Two

The first private event request came from a source I would have laughed at six months earlier: my father’s company.

Their board wanted a “local, authentic venue” for a product launch. Translation: they needed to look like they supported the city while selling a software solution the city couldn’t afford. Their usual hotel had “scheduling conflicts.” Translation: someone called the hotel and told them the press would ask why the Chens weren’t welcome at their own daughter’s restaurant. The hotel said they were booked until 2037.

A junior assistant who had dated a line cook in college emailed our general inbox. You could tell she was new by her punctuation.

Hello! We 🙂 are looking for a space that reflects community 🙂 and heritage ! Can you host 120 on the 15th? Budget is flexible.

I stared at the screen. I thought about all the ways a younger version of me would have said yes out of a grief that called itself professionalism. Then I opened a blank document and wrote a proposal titled Event Policies: The Phoenix.

It laid out terms in simple language: living wages for staff, equitable vendor partnerships, a restitution surcharge paid into the scholarship fund for any client with a history of documented exploitation, and—most revolutionary in this city—a requirement that the client’s speech include five minutes honoring the workers who built their product and the communities their product would change, for better or worse.

I attached it to a quote that set our per-head rate slightly higher than their usual, not because I could fleece them, but because the price of dignity is not a discount.

I expected a no. I got a maybe. Then a yes, with language that suggested someone in their legal department had cried and then shrugged.

I didn’t sleep for two nights. Not from fear. From planning. There is a high you only know when you realize you invented the standard and now you have to live it.

Two days before the event, my father came in.

He stood just inside the threshold like the carpet was lava.

“We need to talk,” he said.

“We need to keep your reservation,” I replied, failing to suppress a grin.

“You can’t extort a surcharge from us for a scholarship named after a man who ran a small kitchen.”

“You’re right,” I said. “It’s not extortion. It’s restitution. And Mr. Cho ran the kind of ‘small kitchen’ that taught the biggest truths I know: that heat makes things rise and hands make things safe.”

He glanced around, as if looking for his old place at table six like a dog returns to a door it can’t admit is locked.

“You’ll ruin us,” he said finally. “This will be bad press.”

“For once,” I said, lowering my voice enough that only’ he could hear, “the press isn’t the point.”

The event ran clean. Our staff wore their right names on their right chests. The food tasted like it remembered grandmothers. The donors clapped. The PowerPoint glowed. When it was time for the required five minutes, my father adjusted his tie and walked onstage.

I expected defiance. I got something else: performance.

“I want to thank the people who often go unnamed,” he said, gesturing toward no one and everyone. “Engineers, line cooks, men like Mr. Cho—”

There was a sound in the room, a small one, but very clear. The sound of eyes rolling.

But he did it. He said what I required. He paid what we demanded. It’s not redemption. It’s a receipt. Sometimes that’s the best you can ask a man like that to hand you with both hands open.

Afterwards, near the back stair, he waited for me. The hall smelled like frying garlic and fresh lilies—joy and funerals making soup.

“I paid your surcharge,” he said. “We won’t book here again.”

“You’re always welcome,” I said. “Under the same terms.”

He looked like he might say something brief and human. He didn’t. He walked away.

I stood for a minute with my palm flat on the cool tile, letting the heat of the kitchen steam my eyes. Sometimes the only apology you get is a check made out to a future you’ll never see. I could live with that. Mr. Cho’s scholarship fund gained enough to send three kids to culinary school that year. One of them came back to stage with us, quiet as a shadow and twice as fast.

A week later, James posted a photo from a “new favorite” spot with a caption about supporting rising chefs. Comments asked about his sister’s restaurant. He didn’t reply. He didn’t need to. I had long since stopped living my life in his captions.

The city noticed anyway.

A food writer who has a way of eating without devouring people walked in on a Tuesday, sat at the bar, ordered the dumplings, then asked if she could talk to the owner about wages. I did not panic. I handed her the printout of our pay sheet with names redacted and the photo of our staff board where we track PTO in sharpie next to dessert specials. She wrote a piece titled What Happens When a Restaurant Treats People Like the Menu. On the night it published, a line curled around the block. We hired two more part-time dishwashers and raised wages again.

And one crisp afternoon, while I was balancing the ledger with a pencil and a patience I wish I’d had for myself ten years ago, a woman stepped into the doorway and pressed a hand over her mouth.

She had my eyes and my grandmother’s shawl. Only I’d never met her.

“Are you Emma?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“I’m Phuong,” she said, lowering her hand. “Mr. Cho’s daughter.”

I stood so fast my chair scraped.

We sat in the back room and traded photographs like baseball cards that mattered: Mr. Cho at twenty in a pressed white shirt; me at ten with almond crumbs on my chin; a dark-haired girl stirring a pot taller than she was; Teresa carrying two trays like a saint carrying the good news.

“I was afraid to come,” she admitted. “I left young. My father and I… we were both stubborn. I didn’t know if you would be angry.”

“How could I be angry,” I said, “when the man who raised me in this room came from you?”

She laughed the kind of laugh that cleans a wound.

We walked the kitchen together. Hyejin pressed a bao into her hand like a sacrament. Marco bowed, dramatic and sincere. Teresa kissed her cheeks. We cried, all of us, in an environment not known for letting water escape.

When she left, she said, “Home is not a building. But you made this room feel like one.” We hugged by the back door in the smell of sesame oil and wet leaves. When you’re not expecting it, life puts you in the right scene and rolls silently.

On the anniversary of the worst dinner of my life, I closed the restaurant early.

We set a single table in the center of the room, no linens, just wood and stories. I invited twelve people who had made me—staff, friends who held my phone while I learned not to answer it, the scholarship kids, Mr. Cho on a video call who tried and failed not to cry.

I lit the red candles my mother always brought out for holidays I eventually stopped attending.

We ate dumplings and laughed the kind of laughter that doesn’t point at anyone. In between courses, we told the most selfish stories we could remember—the times we did exactly what we wanted, and it hurt no one, and that changed everything. Hyejin said she’d taken a solo weekend at a motel with a pool and no wifi. Marco said he’d learned to say no in two languages. I said I’d bought almond cookies for a kid in line who reminded me of me.

At the end of the night, I poured tea and stood with my palm on the bar to steady the way my heart still raced at microphones.

“To the people who call us failures,” I said, lifting my cup, “may they someday learn the difference between the noise of applause and the sound of a life that fits.”

The room clinked ceramic.

Later, when the lights were off and the locks were turned and the world outside forgot us, I walked the length of the dining room and touched each chair the way a watchman touches the posts. The neon sign out front reflected softly on the glass: The Phoenix.

It is a cliché to name the thing you built after the thing you survived. But sometimes clichés are simply true symbols too honest to be original.

On my way out, I noticed a letter slipped under the door. No return address. Unmistakable handwriting. I did not open it. Not because I was afraid. Because I knew what it contained: the same pitiful calculus my parents had been doing my whole life—how much they could get away with calling love.

I left it on the host stand and went home.

The next morning, before the first pot of tea, I took that letter and dropped it in the recycling with a stack of cardboard from the last delivery. Mr. Cho would have scolded me if I’d wasted paper.

At eleven a.m., just before lunch service, a family of four sat at table six. Not my family. A girl pointed at the lanterns. A boy drummed chopsticks. Their mother wiped sauce from her husband’s chin and laughed.

I brought them almond cookies—two each, three for the girl who pulled a report card from her backpack like it was a treasure map. I posted it on the corkboard. I took a photo and texted it to the staff. Marco added three exclamation points. Hyejin sent a heart.

My phone buzzed again. A message from an unknown number.

Heard the place is yours now. Maybe I was wrong about the kind of leader you are. —Dad

I stared at the words for a long beat. Then I typed five of my own:

Keys are for owners. —Emma

I slid the phone into my apron, tied the knot tighter at my back, and stepped into the dining room where a dozen conversations overlapped and nobody needed to be quiet to be worthy.

The kitchen bell rang. The first order of the day came up hot.

I carried it to table six.

END!

News

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

I Paid $8,600 To Help My SISTER Move Abroad. Then MOM Texted “You Don’t Count As Family”. CH2

My Parents Said: “I Paid $8,600 To Help My SISTER Move Abroad. Then MOM Texted ‘You Don’t Count As Family’”…

My Parents Said: “Apologize Or You’re Banned From The Wedding”—So I Ended Their Money Flow. CH2

My Parents Said: “Apologize Or You’re Banned From The Wedding”—So I Ended Their Money Flow Part One My mother…

My Brother Kicked Me Out of Our House. CH2

My Brother Kicked Me Out of Our House Part One The head of HR smiled like the first person…

End of content

No more pages to load