My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives…

Part One

The sound that finally cut through the fog wasn’t my mother’s voice—sharp and triumphant as a slammed door—nor my father’s breathing, fast with adrenaline and righteousness. It was Ava, barefoot in the doorway in her unicorn pajamas, whispering, “Mom?” like a secret she wasn’t sure the room would allow.

I remember every small, unimportant detail that should have vanished under shock. The citrus cleaner on the kitchen counters. The way the winter light made everything look like a photograph taken by someone who loved their house more than the people in it. The beige rug I had saved three paychecks to buy. The warm trickle down my hairline. Somewhere inside, the part of me that still thought my parents were a problem to solve reached for an apology. And then another part—the part that had bled away piece by piece every time I covered my sister’s overdraft or nodded through my mother’s barbed jokes—picked up the pieces and put them into place.

“Get out,” I said. It came out like cold air, like a window opened in January.

Mom’s mouth lifted on one side. “Or what? You’ll call the police on your own parents?” She said parents like a magic word that would change the rules of physics.

I didn’t answer. I crossed the room to Ava and put my hand lightly on her back. I could feel the flutter of her heart through cotton. “Come on,” I told her, and we went down the hallway and into my bedroom. I turned the lock with hands that shook only a little.

Ava’s lip quivered. There was a smear of cinnamon toast on her cheek where I hadn’t had time to wipe it. “Why did Grandma hit you?” she asked, fiercely whispering, like you do when you’re eight and braver than your bones.

I knelt so we were eye-to-eye. I did not say, Because Grandma learned early that hurting people is the same as having power or Because I let them think I was still the daughter who offered her cheek instead of her conditions. I said, “Because she was wrong, and sometimes when people are wrong they would rather be loud than sorry.”

We slept with the bedside lamp on because darkness has a longer memory than daylight. By morning, my eye had bloomed into a bruise that made me look like someone I would cross the street to help. My parents had refused to leave, declaring our duplex “family property” with a certainty so blind I almost admired it. They drank my coffee, left their shoes by my door, took up oxygen I’d carved out for the life Ava and I were building like pioneers with a hammer and a savings account.

I slipped Ava into her favorite blue dress with the pockets, brushed her hair gently around the tender places her small body held last night’s fear, and drove her to school. “We’re going to be okay,” I said, and this time my voice didn’t wobble. She believed me, because she has spent her whole life believing me. As she climbed out of the car, she turned back. “Are you okay?” she asked, with the balled-up courage that makes children old.

“I am now,” I said, and meant it.

The courthouse smelled like paper and coffee and the particular bureaucracy of protection. I told a woman in a navy blazer what had happened. I told a doctor at the ER what had happened. They wrote it down because that is how truth survives when people try to wrestle it back into silence. I sent texts—to my manager at the IT firm, to my neighbor Mara, to my cousin Sarah who spent most of her life translating between our families like a UN delegate with better snacks.

At noon, a judge handed me an emergency protection order, stamped and real. It wasn’t a magic shield. But paper made from trees is stronger than bone when it shows up in the right hands. Officer Ramirez—jaw of granite, eyes kind as a Saturday—walked it out of the courthouse and into the air like a declaration. “We’ll serve it today,” he said. “You did the right thing.”

I didn’t tell him the other thing I had already done. I didn’t explain the LLC called River Birch Holdings that held a deed inside it like a secret. How two years earlier, when our old block started going, one by one, to cash offers and phrases like highest and best and tear-down, I’d noticed a foreclosure notice in the classifieds that looked like my childhood home. How I had called a number at the bottom of a form and expected to be laughed off the line. How Miguel, my former boss and the kind of man who says “show me your spreadsheet” like some say “show me your heart,” had offered to split the down payment and keep his name out of it. “Pay me back before you ever pay me interest,” he’d said, and then stuck a handwritten note on the check that read, For Ava’s treehouse fund, eventually.

I hadn’t told anyone because secrets are only safe if you plan to use them to keep someone else safe. My parents had been renting from a property manager ever since, paying late like a season.

Tasha, the property manager with a nose ring and a moral spine, picked up on the first ring when I called her in the courthouse parking lot. “They’re three months behind again,” she said, apologetic, like it was her fault my parents treated due dates as opinions.

“Hold the notice,” I said. “I’ll handle it.”

She whistled softly. “You sure you want to be the one to pull the pin?”

“I’m sure I want to be the one to put it back in my pocket,” I said.

When I got back to the duplex, my parents were sitting on my couch like they were the couch. Dad had his shoes off. The sight sparked something old and unfair inside me—the part of me that learned as a child that food tastes better if you can ignore the tension at the table. Mom held out her phone. “Kayla’s landlord won’t give her until Monday,” she said without preamble. “You’ve put her in an impossible position.”

“You put her there,” I returned calmly. “But I imagine she’ll do what she always does when you ask her to jump.”

Mom narrowed her eyes. “Everything you have is because of us.” She gestured around my modest living room like a king gesturing at a valley he thinks grows out of his hand.

I looked at the bookshelf my head had hit. The picture of Ava at the park last summer on the top shelf, hair flying like a question mark. “Everything I have,” I said, “is despite you.”

I didn’t argue. I didn’t rage. I survived the rest of the day the way we survive the too-long endings of bad chapters: one small, unromantic act at a time. I called the locksmith. I created a paper trail. I picked up Ava and we made grilled cheese and I let her watch TV on a school night because sometimes grace looks like bending a rule you wrote yourself.

The texts came from new numbers because I had blocked old ones. You’ve embarrassed this family. Ava needs to learn who the real villains are. You will regret choosing outsiders over your own sister. My phone lit up blue and I set it face down on the kitchen counter and braided Ava’s hair while the griddle hissed. Mara dropped off cupcakes with neon icing. Sarah sent a string of knife emojis and then a paragraph that translated to I’m here, no matter what. I sent back a heart and bring Tupperware.

I let them stay.

Not because I couldn’t remove them. I could have walked Officer Ramirez over to my living room and held up the paper with its official, square edges and watched their faces learn what consequences look like when carved out of law instead of guilt. But paper gets stronger when the story underneath it is undeniable. So I made the safer version of a dangerous choice. I took Ava and two duffel bags and we stayed with Mara for three nights. I left my security camera app running. I screenshot texts. I asked Sarah—in her neutral translator role, the one she hated but was good at—to text my parents from her phone and ask if they planned to leave my home voluntarily. They wrote back Not until Nicole transfers the money. I couldn’t have scripted it better if I were the petty screenwriter I wished on my worst days I could be.

On the third day, Miguel called. “You good?” he said, which from him meant Are you safe enough to be the protagonist of your own life?

“I am,” I said. “It’s about to get worse for them and better for me.”

“Good,” he replied gently. “That’s how I’ve always organized spreadsheets.”

We served them—Tasha and the law served them—the eviction notice with thirty days and all the appropriate headings attached. The look on my mother’s face—shock, outrage, and the dawning realization that this world, the one that can be turned against you as easily as a rug pulled out from under your feet, was also the one you’d used to pull rugs out from under people—is one I will tell Ava about when she’s thirty-five and making her own decisions about who sits at her table.

They moved nothing for two weeks. It wasn’t denial. It was a weapon. My father’s way of saying You owe us not just your money but your hours and your hands. He’d taught us early that love looks like ransom. On day fifteen, Tasha left a voicemail with words about “abandonment of property” and “the compressed timeline for turnovers” that my parents would have understood if they understood anything beyond their silences and our reluctances.

Kayla found me in the shampoo aisle because life is sometimes very on the nose. Her cart was an altar to expensive brags—hair masks, sheet masks, masks for the mask that her life was. She looked me up and down like my plain jeans were a diagnosis.

“You think you’re better than us because you got lucky with some tech job and some fake company on paper?” she asked, tossing a ten-dollar bottle into her cart with the flair of someone who has never had to look at a unit price.

“I think I have stopped auditioning for a role you keep getting cast in,” I said. “And I think the stage is collapsing.”

“What are you even talking about?”

“You’ll know soon,” I said. People like my sister treat consequences like hurricanes—storms you can see from space and still pretend won’t hit your house.

Day thirty arrived with a sky so blue it looked like fiction. Ava slipped her hand into mine as we walked across the street to the house where my mother had once measured my worth by how quiet I could cut carrots. The front yard was a yard the way an abandoned theater is still a theater if you squint: plastic bags tangled in the hibernating rose bushes, folding chairs that sagged with how often they’d carried summers, my mom’s patio swing rusting at the joints like a woman who sits too long in her own meanness.

They saw us. My mother rushed forward with a suitcase that had been to more vacations than apologies. “Nicole,” she said, drawing the vowels out like a handkerchief. “You can’t be serious.”

“You hit me in my house,” I said. “In front of my daughter.”

Her mouth made a shape like remorse and produced nothing. “We’re your family,” she said. “You’re throwing us out like garbage.”

“You threw me out of family first,” I said. “And then you threw your hand. Garbage has a smell. You taught me how to recognize it.”

My father loomed, shadow long across the patchy grass. “You think money gives you power?” he sneered. “You’ve become arrogant. You’re just a tenant who bought herself a crown.”

I looked him full in the face for the first time in years. “No,” I said. “I became the landlord of my own life. And yours.”

He reached out and I saw Ava, from the corner of my eye, take a small, brave step forward. “You shouldn’t have hurt my mom,” she said. The timber of her voice made him flinch. “You lied about love.”

Something in my father’s eyes shifted like ice breaking on a river. Maybe for the first time, he saw himself from the other side of the story. He dropped his hand. That was the only mercy I was willing to notice.

Mom clutched her handbag like you clutch dignity when you’ve sold it for less than it was worth. “You’ll regret this,” she hissed. “You’ll understand when she abandons you,” she added, jutting her chin at Ava, because spite taught early can’t help but prophesy.

“No,” I said, Chin up like mine on her small brave face. “I regretted letting you stay this long.”

I didn’t slam the car door. I didn’t look back. I told Ava we were going to get the best tacos at the truck on Fairview and that she could have Jarritos and that we could buy a lavender plant for the porch of our new house and that we didn’t live in fear anymore.

I didn’t tell her that later, with the kitchen light making our new walls look like security, I would sit down with a cup of green tea and a notebook and write a list with two columns: What I owe and What I no longer do. The first list had rent and therapy and a pair of sneakers Ava had circled in a catalog with hopeful dots. The second list had apologies for other people’s choices and loans to adults who prefer tears to job applications and the color of silence my mother likes best when there’s a check attached.

I did not sleep easily that night, but I slept honestly. That’s a start.

Part Two

No one tells you that peacemaking looks like a calendar. Therapy on Tuesdays, Ava’s art class on Thursdays, working late on the nights that memories don’t fight fair. Routines are rebellions when you come from a home where love had a curfew you never knew until you missed it.

There’s no montage for the months that followed—just the kind of simple maintenance storytellers usually skip. I filed for a permanent protective order and sat on a hard bench in the echoing hall while a clerk typed like my protection was a poem she’d memorized. I called the credit card companies and said, evenly and without tremor, “No, that is not my account,” and “Yes, I’ll hold,” and “Thank you for the reference number.” I took a Saturday morning class at the community center on small claims court because nobody tells you that dignity sometimes requires a filing fee and section 7(a) of a statute that looks like a puzzle.

Officer Ramirez came by twice a week for a month and then once a week for two more, the way police resources allow when you are lucky and protected and someone in the precinct knows you as the woman who did the brave thing before coffee. He dropped off a packet about safety planning written in font too cheerful for its content and pointed out that I needed a brighter porch light. “Dark spots are where fear grows,” he said, and screwed in a bulb with a wattage that made the world look accountable.

Tasha texted me the day the house emptied. Keys collected. Walkthrough: baseboards scuffed, patio swing rusted beyond salvage, a wine stain on the hallway runner in the shape of regret. I sent her a thank-you emoji that looked inadequate and promised I’d drop off a gift card.

Sarah sent me a screenshot from Facebook even though I had asked her not to. My mother had posted a status that said Some people forget who held them when they cried with a picture of a young me on her knees by the Christmas tree. The comments were the usual mix of “hugs, friend” and Midwestern scolding that passes for care: Sometimes daughters just need to learn the hard way. I didn’t reply, to her or to Sarah, because social media isn’t where truth goes to see the doctor.

Miguel and his wife took Ava and me for pizza and asked if we were ready for a tiny backyard dog. Ava started a campaign with a PowerPoint and a schedule in crayon. Two weeks later, we brought home a rescue mutt who looks like he’s made of all the other dogs’ leftovers and answers to Beans like the universe meant it.

Kayla didn’t protest when her apartment evaporated, probably because she’d flown to Miami to clear her head and had to come back to clear out her closet. Sarah told me Kayla insisted our parents crash with her for a week and then changed the locks when my dad ate an entire pint of ice cream labeled Kayla’s Healing Food.

Three separate times, unfamiliar numbers pinged my phone with pls, we’re cold, your father’s meds. I didn’t answer. That’s how you rebuild a spine. You put down boundaries and then you hold on to them when they start to tremble in your hands.

Meanwhile, life got very ordinary in exactly the ways I used to pray for. Ava’s cast came off with the kind of scary blade that is only scary if you don’t know doctors. She painted small houses with big windows and two stick figures under a sun that smiled too hard. We hung them on our fridge and it looked like a museum curated by a person who believes the world can be fixed with primary colors. Beans chewed the leg of the dining chair and looked contrite and then did it again because dogs are honest.

I found a therapist who didn’t ask And how does that make you feel? like it was a trap. Dr. Cho is a small woman with a wardrobe of cardigans that look like safety and a row of books behind her that she rarely references because she has the rarest gift: the ability to be quiet while a story tells itself out loud. She didn’t say, It wasn’t your fault because she didn’t have to. She said, “Tell me about what you learned to do with your hands when someone looked at you the way your mother did.” I showed her. We taught them other tricks.

It is one thing to be the victim in a story. It is another, stranger thing to be the woman who chooses not to be. People do not know how to greet you. Some step back because your boundaries make them review their own. Some lean in with the graceless curiosity of tourists. So, you evicted your parents? they ask, eyes bright like gossips at a wedding. I learned to say, “I followed the legal process to evict dangerous tenants from a property I own,” and then, if they didn’t know when to stop, “Would you like me to send you the restraining order in an embossed frame?” It is astonishing how quickly manners return.

On a damp March morning, I found a letter in my mailbox—not a bill or a postcard but an actual letter, with my name written by a hand I knew like you know the shape of your own jaw. My mother’s script had always leaned forward as if trying to arrive before itself. I held it in the hallway and felt, absurdly, like a person in a period drama about to be delivered news of war.

Nicole,

You have made your point. We are in dire straits. Your father’s health relies on medications he cannot afford without help. We raised you to be better than this. Where is your compassion? Where is your loyalty? We are your parents. Blood does not change because you think it should.

If you want to talk, call us on the number at the bottom. But do not think for a second that what you did was right. Someday your daughter will treat you the same.

Mom

She underlined mom twice like it would rewrite the last four months. I put the letter on the kitchen counter. I made tea. I took a picture of the letter and sent it to Dr. Cho with no caption. She replied, Bring it. We’ll read it out loud together and decide what parts belong to you and what parts don’t.

At our next session, I read and cut. We are in dire straits—belongs to them. Your father’s health relies on medications—there are programs for that (I would send a list). We raised you to be better than this—this isn’t about better, it’s about safe. Where is your compassion?—with the eight-year-old I live with. We are your parents—words with a biological meaning and no operational one. Someday your daughter will treat you the same—if I earn it.

I wrote back a week later because time is a boundary too.

Mom,

Here is a list of resources for medications. Here is a number for a social worker at the city office who can connect you to rental assistance. Here is a brochure for a domestic violence support group that you qualify for because violence is violence even if you think you had your reasons. If you would like to discuss an apology, restitution for the rug and bookshelf you damaged, and a plan for supervised, short visits with Ava in a neutral location after six months of your individual therapy, my attorney will coordinate dates.

I will not send money. I will not meet privately. I will not allow you to speak to my daughter without me present.

Nicole

I did not add I love you because love is an action. It shows up in safety. It shows up in recovery. It shows up in time. I would not inscribe a sentiment that has to be earned in pen that lasts longer than most promises.

The reply came in a text from a new number—of course—three days later. You’re cruel. You’ll pay for this. There is always one last splinter of a mirror before it shatters all the way. I blocked the number and took Beans to the park and taught Ava how to tell when dogs want to be pet by looking at their tails because trauma makes you cautious and caution can be remade into kindness.

And then—the part that sounds like fiction because justice rarely arrives in a straight line—the district attorney’s office sent a letter. It didn’t come with sirens. It came with an envelope and a case number. Assault, criminal trespass, violation of a protection order. My mother pled to a lesser charge and community service because there is a version of mercy I can live with. My father took a class about anger that he will joke about to his friends if he has any left, and I will not be there to hear it. They didn’t go to jail. They went to a kind of school with a test they’ll keep taking every day.

Kayla pretended none of it touched her and then started a GoFundMe with a picture of herself in better lighting than I thought possible. It didn’t gain traction because the internet has a sixth sense for performative grievance. She called Sarah and cried. Sarah sat on the edge of her tub and listened with the kind patience of a woman who is always tired and always there. “I can’t help you,” she said gently, and hung up and called me and we talked about nothing important for an hour because that is what community is when there’s nothing left to fix.

On a Sunday in May, Ava and I planted lavender along the front walk of our little house. The soil was stubborn and the day hot and Beans kept trying to help by digging holes in exactly the wrong places. Ava wore her oldest shorts and a determined expression. “This is how we smell like something good,” she said, patting dirt around a root ball like tucking a child in. “This is how we tell the bees we want them.”

I posted a picture on the neighborhood group with the caption, We don’t live in fear anymore. I didn’t tag anyone because dignity is louder when it isn’t trying to be heard.

A month later, I got an email from a junior college near my office asking if I’d speak to their evening class about basic cybersecurity. “Most of our students are women reentering the workforce,” the coordinator wrote. “Many are leaving unsafe situations. They need someone who can make strong tools sound simple.” I said yes because yes is the word I am teaching myself to use generously. The classroom smelled like dry erase markers and ambition. I showed them how to set up two-factor authentication and how to spot phishing emails and how to make passwords out of sentences like MyD0gBeansEatsLavender! and we laughed and then a woman in the back raised her hand and asked, voice catching, “Is it okay to block my mother?” and I said, “Yes,” with a conviction that could have powered a city.

On the anniversary of the day my parents hit me in my own living room, I did not mark the date. I took Ava to the public pool. We ate popsicles that stained our mouths unnatural colors and we looked like we had kissed a rainbow. At home, I found a pen that had run out and threw it away and felt an unreasonable sense of accomplishment because sometimes healing looks like not keeping things that don’t work.

There is no epilogue where my mother learns to bake apology cookies and my father builds a swing for Ava and Kayla becomes the aunt who shows up with glitter. There is a scene on a sidewalk fifteen months later where I see my mother across the street and she freezes and I do not. She doesn’t say my name. She looks at Ava, who doesn’t look back. She mouths something like mercy and I lift my chin a millimeter and go on my way because mercy isn’t a bridge you can run across. It is a raft you build yourself and invite people onto only after they learn to swim.

If you are waiting for me to say I forgave them, I don’t know if I have. I forgave myself. I chose Ava. I chose the version of me that does not bleed to make other people warm. I chose lavender and not rugs and slow dinners and not quick fixes and a dog that chews table legs but not dignity. I chose a life that smells like something good, where bees know where to land.

That first night, when Ava fell asleep in our new house with the porch light on bright enough to make fear find somewhere else to be, I sat at the tiny kitchen table and wrote a letter I will give her when she is twenty-one. It begins:

Dear Ava,

I kept us. When my mother taught me the wrong meaning of love, I chose to teach you another. When my father taught me that safety is a favor, I chose to build it as a right. When your aunt taught me that entitlement is a hobby, I chose work.

Mercy without access is still mercy. Accountability without cruelty is still justice. Lavender needs sun and ordinary water. We can handle that.

Love,

Mom

I have learned that “destroying their lives” was the wrong verb. I didn’t destroy anyone. I removed the scaffolding that let them think gravity didn’t apply to them. The fall looked like destruction because they had lived so high above consequence for so long. What I built in the space where their demands used to live looks smaller to outsiders: a fence, a porch light, a certificate with a case number, a row of purple shrubs, a fridge full of paintings and groceries that are mine and paid for and shared.

Sometimes, on warm evenings when the air holds its breath between daylight and a porch light clicking on, Ava and I stand in the yard and listen. You can hear the soft industry of bees in the lavender. You can hear the neighborhood moving itself gently toward night. You can hear a woman in a small house exhale the life she was told she could not have.

END!

News

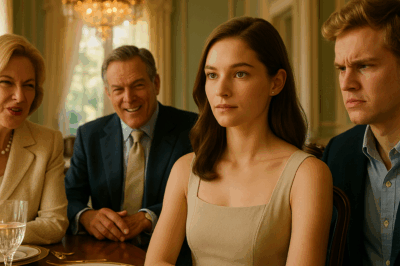

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… CH2

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… Part One The pen…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… CH2

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… Part One The…

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… CH2

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… Part One The emergency room’s…

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead. CH2

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead Part…

End of content

No more pages to load