My Nephew Mouthed, “Trash Belongs Outside” Everyone Smirked I Nodded, Took My Son’s Hand, And Left

Part 1

“Waiters eat in the kitchen. Trash belongs outside.”

That was the sentence.

Thirteen-year-old Caleb didn’t shout it. He didn’t mumble it. He said it in that casual, cruel, very deliberate tone kids use when they know there’s an audience and they’re performing.

He pointed his fork, still slick with steak juice, at the open sliding door that led off the deck toward the yard. The breeze lifted the white tablecloth. Wine glasses chimed softly. My mother’s fairy lights glowed overhead like they were decorating a scene from some magazine about “perfect lakeside living.”

And my son froze.

Leo was seven. Too big to be a baby, too small to be anything but tender. He sat at the corner of the giant outdoor table, his sneakers barely brushing the rung of his chair, a paper napkin folded in his trembling hands. He had just reached for a second roll.

Caleb’s words hung above his plate like flies.

Slowly, Leo turned to look at me.

His eyes were wide and wet, but there were no tears yet. This was the moment he’d been trained for by cartoons and classroom posters and every “tell an adult” speech he’d ever heard.

The bully had spoken. Now, the adults would fix it. His gaze moved to his grandmother. To his aunt. To the people who were supposed to be the safety net.

My mother, Evelyn, didn’t even flinch. She swirled her wine in her glass, watching the color cling to the sides like that was the most interesting thing in the world. She raised it to her lips and took a slow sip, eyes on the lake, not on her grandson.

My sister, Vanessa, laughed.

Not aloud. Not one of her big, theatrical cackles. Just a short, sharp exhale, and then that smirk. That tiny, satisfied curl of the lip.

It was like watching a verdict pass over someone’s face. The jury had made its decision.

No one told Caleb to apologize.

No one told him not to talk like that.

No one reached for Leo’s hand.

In that soft clatter of cutlery and expensive glass, I heard something louder than a scream: approval.

I could have said a thousand things.

I could have stood up and told Caleb to get his scrawny self back to the kid’s table. I could have asked my mother why she thought drinking a pinot noir I paid for was more important than defending her grandson. I could have reminded Vanessa that the deck her son was holding court on existed only because I’d signed a check big enough to make the contractor’s eyes water.

Instead, I did nothing.

I pushed my chair back. The legs scraped against the wood with a long, low screech that made everyone look up.

I stood.

Leo’s hand was still on his napkin. I took it gently, peeling his fingers away from the crumpled paper like they were stuck there.

“Come on,” I said, my voice calm and clear. “We’re going.”

Vanessa blinked. “Lena, don’t be dramatic. Caleb was just—”

I ignored her.

I didn’t yell. I didn’t flip the table or smash the plates, though for a second I saw myself doing it, white china exploding like fireworks over the lake.

I just walked.

Leo slid off his chair and followed, our hands locked together, his steps quick and uneven. The deck boards flexed under our weight. Behind us, cutlery clinked again, nervous and disjointed.

I stepped through the sliding door into the kitchen—the kitchen I’d paid to remodel, with its marble countertops and farmhouse sink and professional-grade stove—and kept walking.

No one came after us.

The front hall smelled like the lemon cleaner Vanessa used to impress guests. The framed family photos on the wall watched us leave: younger versions of me and Vanessa smiling with summer tans, Mom in big sunglasses, Caleb as a toddler reaching for my hair.

I didn’t stop to look.

I opened the front door, cool evening air washing over us, and led my son down the steps, across the gravel drive, to my SUV.

Leo climbed into his booster seat without a word. I buckled him in, fingers gentle on the straps.

His eyes were dry.

He wasn’t crying.

That was somehow worse.

My nephew had called him trash and my family had answered with smirks. My son had looked for help and found silence. He’d done the math faster than I ever could—he was not safe here—and his body was already starting to disappear into itself.

I closed the door, walked around the SUV, and slid behind the wheel.

For a moment, I just sat there, my hand on the ignition, watching the house.

Through the big picture window, I could see silhouettes moving around the table. Someone—Vanessa, probably—raised a glass. Mom’s head tipped back in another drink. Caleb’s outline slouched in his chair like he’d won something.

He had.

He’d won. I’d paid. Leo had lost.

I turned the key.

The engine hummed to life, low and familiar. The driveway was long, lined with pines Vanessa liked to say made the lake house feel “exclusive.” My headlights cut through the shadows, illuminating the gravel. I reversed, turned, and pulled out onto the main road.

The drive home was only thirty-five minutes.

It felt like a lifetime.

Leo didn’t say a word.

He didn’t sob or sniffle. He didn’t kick the back of my seat or ask why we were leaving or beg to stay, which he had done every other night we’d spent at the lake house. He just sat, seat belt tight across his chest, his small hand pressed against the window, watching the world go by.

Streetlights slid across his face in intervals—light, dark, light, dark—like someone was flipping a switch.

He looked… gone.

I recognized that look.

I’d seen it in bathroom mirrors, in car windows, in the reflection of polished conference room tables. It was the face I’d worn as a kid when my mother criticized my “tone” so harshly I had to swallow my words whole. It was the face I’d worn at sixteen when Vanessa told me my acceptance letter to the state university was “cute” but not nearly as glamorous as the acting conservatory she pretended she’d attend.

Disappear so they can’t hit you. Go numb so the words bounce off instead of sinking in.

Dissociation.

My six-year-old—my baby—was already mastering the family survival skill I’d perfected over three decades.

Something inside me snapped.

Not like a twig breaking. Not loud and messy and sharp.

It snapped like a lock sliding into place.

A mechanism inside my chest, hidden behind years of duty and guilt and habit, turned over and clicked.

My fingers tightened around the steering wheel until my knuckles went white.

Fine, I thought. If this is going to be an audit, let’s make it a thorough one.

For years, my mother and sister had their own little nickname for me.

They called me the calculator.

“This is Lena,” Vanessa would say at parties, her voice loud enough to carry. “She stares at spreadsheets all day so we don’t have to.”

“Boooring,” Mom would chime in with a tipsy laugh, patting my arm. “She’s always talking about budgets. It’s like she’s allergic to fun.”

They’d say it like it was a joke, an affectionate ribbing. But the edge was always there.

I was the boring one. The rigid one. The stingy one.

I was a forensic accountant—that was my crime. I made my living following the money trails companies tried to hide. I dug into accounts, line by line, hunting for fraud and theft and all the little creative “mistakes” people made when they thought no one was looking.

To them, that meant I didn’t understand “passion” or “the finer things in life.”

The irony was acidic enough to burn a hole through the floorboard.

The boring job they mocked was the only reason they had a floorboard to stand on.

The rigid spreadsheets they laughed at were the only reason the lake house hadn’t gone into foreclosure three years ago when Vanessa “forgot” to make payments.

They treated me like a walking wallet that had accidentally developed a personality.

I stared at the road, but my mind no longer saw asphalt and headlights.

I saw columns and rows. Debits and credits. Inflows and outflows.

Whenever I got called into a failing business, I didn’t listen to the CEO’s sob story first. I didn’t let their tears or charm color the books. I went straight to the raw data, to the ledger. Numbers don’t cry. Numbers don’t flirt. Numbers don’t make excuses.

For the first time in my life, I turned that cold, high-powered lens on my own family.

Why had I stayed?

Why had I kept signing the checks?

For seven years, I’d been operating under a silent contract. It went something like this:

If I pay enough, they’ll love me enough.

If I cover the mortgage, the renovations, the medical bills, the emergencies, I’ll earn my spot at the table.

If I pour enough money into this family, I’ll buy equity in it—respect, affection, safety. They’ll be too invested in me to hurt me.

I’d treated my mother’s affection like a delayed dividend.

Just a little more, I told myself. Just one more loan payoff, one more renovation, one more “emergency” transfer. The payout will come. It has to.

Then Caleb called my son trash, and my mother smirked.

That smirk was more than cruelty. It was data.

It was proof that my investment had yielded exactly zero returns.

Actually, it was worse than zero. I hadn’t just failed to buy respect.

I had financed their cruelty.

I’d paid for the wine they were sipping while they ignored my child. I’d paid for the deck Caleb stood on when he appointed himself king of the table and banished my son.

I wasn’t a daughter to them. I wasn’t a sister.

Those titles imply relationship. Mutual care. Blood and love.

This was something else.

This was extraction.

They were miners and I was the vein of gold. And they’d gotten spoiled by how easy it was to dig.

The thing about resources, though?

Once a resource becomes self-aware, the extraction stops.

I pulled into our driveway on autopilot. The house was dark, the porch light timer not yet clicked on.

Leo had fallen asleep. His head lolled against the car seat, mouth slightly open, a faint line of drool on his chin.

Exhaustion, what a simple word for what he’d gone through.

I parked, turned off the engine, and sat there a moment longer. The silence in the car didn’t feel peaceful. It felt like the quiet right after an explosion, when dust is still settling and people are waiting to see who stands up.

I got out, opened the back door, and unbuckled him.

He stirred, eyes fluttering. “Mama?” he murmured.

“I’ve got you,” I whispered, lifting him into my arms.

He was getting big; his legs dangled past my waist now. But in that moment, he felt small again. Soft. Warm. My responsibility.

Inside, I laid him on his bed, pulled the duvet up to his chin, and brushed the hair off his forehead.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered to the dark room. “I’m so, so sorry I bought us a seat at a table where we were on the menu.”

He didn’t wake.

Good.

He’d done enough feeling for one night.

I stepped out, closed his door softly, and did not go to my bedroom.

I went straight to my home office.

No overhead lights. I didn’t need them. The twin glow of my monitors illuminated the room in cool, artificial light.

I sat down in my ergonomic chair—the one Vanessa mocked for being “ugly” and “officey”—and woke the computer.

Sadness is a luxury for people who can afford to be helpless.

I couldn’t afford to be helpless anymore.

I didn’t feel like crying.

I felt like working.

My fingers flew across the keys, muscle memory kicking in. I logged into my bank’s business portal, bypassing my personal accounts to go straight for the arteries I knew were bleeding.

It was time to audit the books.

The screen loaded column after column of numbers. Checking. Savings. Investment accounts. Then the list of linked external accounts—the ones labeled “Evelyn medical” and “Vanessa support” and “Lakehouse mortgage.”

Red font stared back at me.

In my line of work, people lie. Receipts lie. Stories lie.

Raw bank data does not.

I filtered for the last thirty days across the family accounts. The system spat out a report:

Transfer to EVELYN MEDICAL STIPEND – $800

Transfer to VANESSA CARETAKER ALLOWANCE – $850

DIRECT PAYMENT – LAKEHOUSE MORTGAGE – $3,200

Total monthly outflow: $4,850.

Almost five thousand dollars.

Every month.

Fifty thousand a year.

I clicked over to the cumulative totals for the last seven years. The number made my stomach swoop.

Over three hundred thousand dollars.

Three hundred thousand dollars I’d poured into people who just smirked while my son’s heart cracked on a deck I paid for.

I didn’t feel generous. I didn’t feel noble.

I felt stupid. Highly educated, well-paid, certified stupid.

My mouse hovered over the “Recurring Transfers” tab.

My hand didn’t shake.

There were no flashbacks to childhood Christmases. No soft-focus montage of “good times.” There hadn’t been any real good times, not with them. Just transaction times.

I clicked.

The list appeared, neat and orderly: every automatic payment scheduled into infinity, little financial IV lines feeding their lifestyle with my blood.

Select all.

A warning popped up: Are you sure you want to cancel all recurring payments to this recipient? This action cannot be undone.

I stared at the line.

“I’m counting on it,” I whispered.

Confirm.

The screen refreshed.

Scheduled transfers: none.

Just like that, the drip stopped.

The mining operation went dark.

Next, I opened my email.

I didn’t pour my heart out. I didn’t beg for understanding or list every way they’d hurt me. I wrote what I knew best.

A memo.

Subject: Notice of Financial Cessation – Evelyn / Vanessa

Effective immediately, all third-party financial support provided by Lena is terminated.

This includes, but is not limited to, the lake house mortgage, medical stipends, and discretionary allowances.

You are advised to arrange alternative funding for all future obligations.

Do not contact me to negotiate.

Regards,

Lena

I read it once.

It wasn’t cruel.

It wasn’t emotional.

It was clear.

I hit send.

The whoosh of the outgoing message felt like a judge’s gavel.

Case opened.

People want to know why I stayed.

Why I paid for seven years if they treated me like this.

It’s a fair question. The answer isn’t love. Not really.

It’s economics.

Specifically, a trap we talk about in finance all the time but almost never apply to relationships:

The sunk cost fallacy.

Sunk costs are money you’ve already spent and can’t get back. Rational investors ignore them. They don’t throw good money after bad just because they’ve already “put so much in.” If a business is failing, you close it. You don’t burn another million dollars to keep the lights on.

That’s how you go bankrupt.

In relationships, we’re terrible investors.

For seven years, I treated my mother’s love and my sister’s respect like a failing stock that was bound to bounce back.

Every time I wrote a check, I told myself, You’ve already put so much in. So much money, so much time, so much pain. If you walk away now, it was all for nothing. You have to keep paying until it turns around.

I was terrified to close the account because that would mean admitting the profit—love, safety, belonging—was never coming.

I wasn’t loyal.

I was refusing to face a bad investment.

Tonight, staring at the blank transfer column, I finally accepted the loss.

The three hundred grand was gone.

It was never coming back.

And that was okay.

Because the only thing worse than losing seven years and three hundred thousand dollars is losing seven years and one day and three hundred thousand dollars and one.

I wasn’t saving the relationship anymore.

I was cutting my losses to save the only asset that still had real value.

My son.

I closed the laptop. The room plunged into darkness.

For the first time in a decade, I went to bed not worrying about their bills.

I went to bed knowing that tomorrow the market would crash.

And I could not wait to watch it fall.

Part 2

Monday mornings usually arrive with the soft tyranny of routine.

Coffee. School drop-off. Commute. Inbox.

This one came in like a pending lawsuit.

I woke up with my decision sitting heavy and solid in my chest, not like guilt, but like a foundation stone. Leo padded into the kitchen while I was making eggs, rubbing sleep from his eyes.

“Morning,” I said, ruffling his hair.

“Morning,” he murmured.

He watched me for a second, as if trying to gauge which version of his mother he was getting today—the tense, distracted accountant or the mom who made dinosaur pancakes on Saturdays.

“Do we have to go back to Grandma’s house?” he asked casually, like he was asking about the weather.

I set his plate in front of him and met his eyes.

“No,” I said. “We don’t.”

His shoulders dropped just a fraction. He took a bite of eggs, chewing slowly.

“Okay,” he said.

He didn’t ask why.

Kids know when you don’t really want to answer.

I dropped him at school. He clutched his backpack straps a little tighter than usual but walked in on his own. No clinging. No last look back.

That was the first dividend on my investment.

At 9:00 a.m., the banks opened.

At 9:05, my phone lit up.

VANESSA: Payment didn’t go through. Fix it.

The text glowed on the screen, followed by more, stacking on top of each other like frantic dominoes.

VANESSA: Mom is stressing out. Do you want her to end up in the ER???

VANESSA: Pick up the phone, Lena. You’re being selfish.

I put my phone face down on my desk.

In any audit, you don’t destroy the first wave of paperwork. You let people generate evidence. You let them show you who they are when they realize the money’s gone.

By 10:30, the strategy shifted.

The caller ID said Mom.

Of course.

In toxic systems, when the attack dog can’t get what they want by biting your ankles, they unleash the martyr.

I took a breath and answered.

“Hello?”

“Lena,” my mother wheezed.

She sounded like she’d sprinted up several flights of stairs with a bag of rocks on her back. Breathless, fragile, frail.

“Hi, Mom,” I said evenly. “What’s wrong?”

“It’s my chest,” she whispered. “It feels… heavy. I can’t… I can’t breathe right. Vanessa told me—” she paused to pant theatrically—“she told me you cut us off. I got so worked up. My heart is fluttering again.”

Her voice shook on the word fluttering, like it was a hummingbird about to die.

“I need my medication, Lena,” she added. “The pharmacy won’t fill it without the co-pay. It’s two hundred dollars. Two hundred. I don’t have it. I’m scared.”

She let that last word hang in the air between us.

Scared.

People like my mother use that word the way extortionists use pictures. Look what might happen if you don’t pay.

“If I don’t get it, I don’t know what will happen,” she whispered. “Do you want me to die over two hundred dollars?”

There it was.

The nuclear option.

For a second—a small, shameful second—the old program in my brain kicked in.

You’re a bad daughter. She’s sick. You’re punishing her over money. Just send it. It’s only two hundred dollars. Is your pride worth her life?

My guilt tried to grab the wheel.

But then I saw Leo’s face again; his small fist clenched around a napkin while my mother smirked over her wine glass.

I remembered how steady that glass had been in her hand. No shaking. No fluttering.

My grip on the phone tightened.

“If you’re having chest pains, Mom,” I said, my voice calm and flat, “that’s a medical emergency.”

“Yes,” she agreed quickly. “That’s what I’m telling you. I can’t breathe. I—”

“No,” I interrupted. “If it’s an emergency, you don’t need a bank transfer. You need an ambulance.”

Silence.

“I’m calling 911,” I said. “They’ll send paramedics to the lake house. They can help you right now.”

“What? No.” The breathy whisper vanished, replaced by her real voice—sharp, loud, very much not dying. “Don’t you dare call an ambulance here, Lena. I don’t need a circus on my front lawn. I just need my pills.”

“If you’re well enough to yell at me, you’re well enough to manage your own budget,” I said.

“You ungrateful little—”

I hung up.

My heart was racing, but my head felt like crystal.

Performances aren’t proof.

In my job, I don’t accept a sobbing CEO as evidence the books are honest. I ask for receipts.

Mom said she needed $200 for heart medication. She said the pharmacy wouldn’t fill her prescription without the co-pay.

Okay, I thought. Let’s see what the pharmacy has to say.

I turned back to my computer and logged into the joint checking account I’d set up as a “medical fund” for her years earlier. I was the guarantor on the attached loan. It was supposed to be for prescriptions, co-pays, specialist visits.

In my head, I’d pictured it like an IV drip—sad but necessary, feeding her health.

On paper, it turned out to be something else entirely.

Because the account was technically joint and I was the legal guarantor, I had full administrative access. No hacking. No backdoor tricks. I was the door.

The site loaded, and I navigated to “Recent Transactions – Medical Account.”

I filtered for the last thirty days.

My mental image of pharmacy receipts and cardiologist co-pays evaporated.

SEPHORA – $142.50

TOTAL WINE & MORE – $218.00

LULU’S BISTRO – $86.00

CINEMA CITY – $45.00

HULU PREMIUM – $19.99

There was not a single CVS. Not a Walgreens. Not a doctor’s office.

She’d spent nearly five hundred dollars in the last week on makeup, restaurant meals, streaming services, and enough pinot noir to drown a small town.

I stared at the screen.

I wasn’t angry.

Anger is hot, messy, explosive.

What I felt was cold and clean. The feeling I get when I find a hidden shell company on the twentieth page of a ledger. The quiet satisfaction of a lock clicking open.

This wasn’t a misunderstanding.

It was misappropriation of funds.

They’d been laundering my guilt into lifestyle upgrades.

But something still didn’t add up.

I’d been pumping thousands into that account every month. These petty charges were annoying—offensive, even—but they weren’t big enough to explain the full outflow.

Where’s the rest of it? I murmured.

I changed the filter from “Recent Transactions” to “Recurring Autodrafts.”

The list shrank.

The small charges vanished.

Only one line survived.

RECURRING TRANSFER – $2,400

Recipient: SJE ACADEMY BURSAR

SJE Academy.

The name poked at something in my brain, like a song I’d heard once in the background.

I clicked open a new tab and typed it into the search bar.

St. Jude’s Elite Academy.

The website loaded in a wash of gold and white. There was the crest—a lion and a shield. The homepage showed kids in navy blazers and plaid skirts laughing on a manicured lawn.

“Preparing Tomorrow’s Leaders Today.”

I clicked on tuition.

Junior High, Grades 6-8: $28,800 per annum. Monthly installment plan available: $2,400.

The number matched the line item down to the last zero.

I sat back in my chair.

It wasn’t medical bills.

It wasn’t private rehab or some secret test she was too proud to tell me about.

I had been paying for private school.

St. Jude’s Elite Academy.

I scrolled through their promotional photos—lacrosse sticks, debate teams, shiny science labs. For a second, the kids all blurred.

Then I saw him.

Caleb.

My nephew, in a navy blazer and striped tie, standing at the edge of a group photo, smirking at the camera in the exact same way he’d smirked on the deck.

The caption: “St. Jude’s Academic Excellence Award winners.”

My throat closed.

While my son Leo wore thrift store jeans and carried a backpack I’d bought on clearance, Caleb was attending the most expensive prep school in the county on my dime.

He’d been calling my son trash from a position of literal, purchased privilege.

And I’d been footing the tuition.

I wasn’t just being exploited.

I was financing my own child’s oppression.

The irony was so sharp it almost made me laugh.

I didn’t.

Instead, I printed everything.

Transaction history. Tuition page. Photos. Terms of the loan. My guarantor agreement for the lake house.

The printer whirred, then spat out page after page into the tray.

The sound was rhythmic.

Whrrr. Slam. Whrrr. Slam.

Like a gavel.

When I had a neat, warm stack of papers, I slid them into a folder.

The audit was complete.

It was time to deliver the report.

Tuesday morning arrived at my front door like a battering ram.

I was pouring coffee when the pounding started.

This wasn’t a polite knock. It was the kind of insistent, angry hammering you hear in movies right before someone kicks the door in.

I glanced at my camera feed.

Mom. Vanessa.

They looked like an amateur theater troupe staging a drama titled “Two Women Betrayed.”

Vanessa paced, gesturing wildly, mouth moving in silent profanity. Evelyn leaned against the door frame, clutching at her chest with one hand and a monogrammed handkerchief with the other, glancing around to see if anyone on the street was watching.

They’d dressed for the part. Vanessa in yoga pants and an oversized sweatshirt that said “CHAOS COORDINATOR,” because of course. Mom in a silky robe and slippers, her hair sprayed into careful waves.

I didn’t rush.

I took a sip of coffee.

It was bitter.

Perfect.

Then I walked to the door and opened it.

“Are you insane?” Vanessa exploded, pushing past me into the foyer without waiting for an invitation. “You cut off the transfers? Are you out of your mind?”

Evelyn staggered in behind her, a hand at her chest. “I don’t know what I did to deserve this,” she gasped. “My own daughter. Leaving me to die over money.”

“The mortgage bounced,” Vanessa snapped, ignoring her. “Mom’s card got declined. The bank called. What the hell are you doing, Lena?”

I closed the door calmly and leaned against it.

“Good morning to you too,” I said.

“This isn’t funny,” Vanessa shouted. “Mom was in the ER all night because of the stress. Her heart—”

“I checked the medical account yesterday,” I said.

Vanessa froze.

Evelyn’s hand dropped from her chest.

I picked up the folder from the entryway table and held it out.

“What is that?” Vanessa demanded.

“An audit,” I said. “You know, the boring thing I do all day so you don’t have to.”

She snatched it from me.

“Page one,” I said, “is the breakdown of the medical expenses account. The one you’ve both been telling everyone I fund out of the goodness of my cold, stingy heart.”

She flipped the first page.

Lines of transactions stared up at her.

“Sephora,” I said. “Total Wine. Hulu. Lulu’s Bistro. All very necessary for heart health, I’m sure. Do you apply the rouge directly to the left ventricle, or—”

“You invaded our privacy,” Evelyn cut in, her voice suddenly full-bodied and strong. “You had no right—”

“I audited a joint account that I own,” I corrected. “But you’re right, Mom. That’s small potatoes. Go to page two.”

Vanessa hesitated.

“Turn it,” I said.

She flipped the page.

Her eyes landed on the highlighted line. SJE Academy Bursar. $2,400.

She went pale.

“St. Jude’s Elite Academy,” I said softly. “Beautiful campus. Impressive curriculum. Very strong marketing about ‘zero tolerance for bullying.’ Interesting branding choice given their clientele.”

“Lena, I can explain—” Vanessa started.

“You can’t,” I said. “Not in a way that will make this okay.”

“It’s for his future,” Mom jumped in, eyes flashing. “Caleb has potential. Public school would crush it.”

“My son,” I interrupted, “goes to public school.”

They both blinked.

“Leo, the trash,” I added. “Remember? The one your grandson humiliated on a deck I paid for? He sits in overcrowded classrooms while I work seventy-hour weeks to send your precious boy to Latin class.”

“That’s not fair,” Vanessa snapped. “You make more than I do.”

“Because I work,” I said. “Because I didn’t quit my job to ‘find myself’ and then somehow never find a paycheck again.”

“Someone had to take care of Mom,” she shot back.

“At St. Jude’s,” I said drily. “Apparently the best heart medicine is six periods a day and an after-school lacrosse program.”

“This is about jealousy,” Mom hissed. “You hate that your sister’s son is going somewhere better than your boy. You’ve always hated it. Your job, your money, it’s all compensation for the fact that you’re cold, Lena. You’re cold and no man ever stays and—”

I held up a hand.

“Stop,” I said quietly. “Do you hear yourself? You are stealing from me and you’re still trying to make it my fault.”

“This is our family,” Vanessa said, planting her hands on her hips. “Families help each other. You can’t just cut us off.”

“I can,” I said. “I did.”

“And what are you going to do about the mortgage?” she challenged. “You’re on the deed, Lena. You’re the guarantor on the loan. If we lose the house, your credit is screwed too. So either you pay up, or we all go down together.”

There it was.

The smirk.

It slid back onto her face, the same expression from the deck. The expression of someone who thought she had leverage. That she’d cornered me.

I smiled back.

It wasn’t a nice smile.

“I’m glad you brought that up,” I said. “Because you’re right. The bank did call. Yesterday. Apparently you haven’t made a payment in three months. They were initiating foreclosure proceedings.”

“Exactly,” Vanessa said, triumphant. “So fix it.”

“I did,” I said.

She blinked. “What?”

“I exercised my right as guarantor to buy out the note,” I said. “I wired the full payoff balance yesterday afternoon. The bank is out. The debt has been transferred to an individual lienholder.”

Vanessa’s mouth twitched. “What… individual?”

“Me,” I said.

I reached back into the folder and pulled out the final document.

It was thick, printed on legal letterhead, with a bright red stamp across the top.

Notice to Quit – Vacate Premises Within Thirty (30) Days.

I handed it to Vanessa.

She read the title, then the first few lines.

Her knees actually wobbled.

“You can’t do this,” she whispered.

“I can,” I said. “I checked with three different attorneys just to make sure.”

“You’re evicting your own mother,” Evelyn said, horrified.

“I’m evicting my tenants,” I corrected. “Tenants who haven’t paid rent, who’ve damaged the property value, and who bully the landlord’s child.”

Vanessa’s hands shook so much that pages slipped from the folder and fluttered to the floor.

“Where are we supposed to go?” she demanded, tears filling her eyes now, real panic creeping in. “We don’t have savings. We don’t have anywhere—”

“I suggest you start by calling St. Jude’s,” I said. “Tell them their star student is dropping out. That should free up twenty-eight thousand eight hundred dollars a year.”

“You’re heartless,” Mom snarled.

“No,” I said. “I just finally stopped treating you like a charity and started treating you like a business that’s been bleeding me dry for too long.”

“You can’t put your own mother on the street,” she repeated, reaching for the banister like it might save her.

“You’re not helpless,” I said. “You’re sixty-one, not ninety. You have a fully functioning body, a fully functioning brain, and a fully functioning mouth that has never had trouble asking me for money. You can use all three to get a job, or apply for assistance. You can sell the lake house furniture. You can move into an apartment.”

“You would do this to your own family,” Vanessa whispered.

I looked at her.

“At this point,” I said, “you are not my family. You’re my creditors. And your credit line is closed.”

I opened the front door. Daylight poured in, harsh and bright, illuminating the dust on their shoes and the panic on their faces.

“You have thirty days,” I said. “After that, the sheriff will remove you.”

“Lena,” Vanessa sobbed. “Please. Don’t do this. We were just stressed. Caleb didn’t mean what he said about Leo. He’s just—”

I thought of Caleb’s mouth forming the words. Trash belongs outside.

I glanced at the driveway.

“Tells you what,” I said gently. “Trash belongs outside.”

I stepped back and pointed.

“Get off my property.”

Vanessa stared at me, shaking.

Mom’s face crumpled in fury. “You’ll regret this,” she hissed. “One day, you’ll need us, and we won’t—”

“I don’t,” I said. “Not anymore.”

They backed out onto the porch, still sputtering.

I closed the door.

Locked it.

Then I went to my kitchen, poured myself a fresh cup of coffee, and sat at my table.

Two chairs.

One for me.

One for my son.

For years, those empty chairs had terrified me.

I thought emptiness meant failure.

But as I stared at them now, the silence felt different.

Not heavy.

Clean.

Part 3

Thirty days is both a long time and no time at all.

For my mother and sister, it was a countdown.

For me, it was a detox.

I expected rage.

I got it.

I expected manipulation.

I got that, too.

What I didn’t expect was how quiet my own mind would become once I’d made the decision not to engage.

The first week after I served the notice, the messages came in a storm.

Vanessa texted late at night, long paragraphs alternating between apologies and accusations.

I can’t believe you’d throw us out over ONE bad night 😡

We’re FAMILY, Lena. Families FIGHT. They don’t evict.

Okay, look. I’m sorry about what Caleb said. He’s a kid. He’s repeating stuff from school. You can’t honestly blame us for that?

You’ve changed. Ever since you got that promotion, you think you’re better than us.

Mom left voicemails.

Long, drawn-out ones, heavy on sighs.

“Lena, it’s Mom. I… I just don’t understand. After all I did for you growing up… I know I wasn’t perfect, but I tried. I tried so hard. I’m an old woman. Do you really want my last years to be spent worrying about rent? Is this the legacy you want to carry? Think about it, sweetheart. Please.”

Legacy.

As if that word hadn’t already been dragged through seven years of financial abuse.

I didn’t respond.

Not once.

The thing about people who are used to your quick compliance is that silence scares them more than anger.

By week two, the tone shifted.

They stopped talking to me and started talking about me.

Screenshots trickled in from sympathetic cousins and old high school friends who still followed Vanessa on social media.

A post with a photo of the lake house view: “Some people care more about money than their own mother’s health. Don’t worry, Mom. Karma’s real. 💔”

A selfie of Caleb in his blazer: “Last day at St. Jude’s. Guess some people in the family don’t think education for the next generation is a priority. But we rise anyway.”

Comments flooded in.

“Wow, that’s cold.”

“So sorry you’re going through this.”

“You deserve better.”

Not a single one of them knew my side.

Not that my family would’ve told it straight even if I had.

I didn’t jump into the comments.

I didn’t post my own version.

I printed the posts and added them to my file.

Data.

By week three, the chaos quieted.

That’s how extinction bursts work. When an old system stops working—when the usual tactics don’t get a response—people flail for a while.

Then they get tired.

Then they pivot.

Or they crumble.

The last week, there were no texts.

No calls.

Just the occasional ping from my lawyer updating me on logistics—sheriff scheduling, paperwork, certified mail confirmations.

The morning of day twenty-nine, I woke up to sunshine streaming through the windows and the smell of bacon.

For a second, I thought I’d overslept and someone had broken into my kitchen to cook.

Then I remembered the conversation I’d had with Leo a few days earlier.

“Can I make breakfast?” he’d asked, eyes shining.

“With supervision,” I’d said. “Always with supervision.”

We negotiated terms: he would be in charge of toast and juice, I would handle anything that involved open flames.

Now, I padded into the kitchen to find him at the counter, standing on a little step stool, carefully spreading jelly on toast. The toaster sat behind him, unplugged, exactly as I’d instructed.

“Morning, Mom!” he said, glancing over his shoulder. “I made you breakfast. Sort of.”

He pointed to the table. Two plates. Two slices of jelly toast. Two glasses of orange juice, slightly too full.

My phone buzzed on the counter.

Sheriff’s department. Voicemail: “Just confirming we’ll be at the lake house at 10:00 a.m. per your attorney’s request.”

I looked at Leo.

Someday, I thought, he’s going to ask me about today. About why I did what I did. About why we stopped going to the lake.

Someday, he’ll put together the timeline—how the eviction lined up with the end of his time with that side of the family.

When he does, I want to be able to tell him the truth without flinching.

“I love your breakfast,” I said, kissing the top of his head.

We ate together.

He chattered about school. About a science experiment with baking soda. About a new kid who liked the same video game he did.

He didn’t mention Caleb.

He didn’t mention Grandma.

The absence of their names from his small daily orbit told me more than any tearful confession could.

They were already fading.

At 9:45 a.m., I dropped him at school, hugged him tight, and watched him run toward the building.

At 10:00 a.m., two counties over, a sheriff’s deputy knocked on the front door of the lake house.

I didn’t go.

I’d seen enough in my line of work to know there’s no satisfaction in watching other people’s panic when the consequences finally arrive. It doesn’t fix anything. It doesn’t refill your accounts or rewind the clock.

My attorney handled it. Papers were served. The law was followed. Vanessa and my mother scrambled.

Later, I heard through the grapevine that they’d tried to stall, then tried to charm, then tried to claim some kind of clerical mistake.

It didn’t work.

They had thirty days and they used every one of them, dragging their feet to the very last.

On day thirty, the movers came.

Not the expensive, white-glove service I’d paid for when Vanessa first moved into the house. This was a ragtag team with rented trucks, sweat-stained shirts, and a timetable.

They packed up the life I’d funded into cardboard boxes.

Furniture they hadn’t paid for. Dishes I’d bought. Decor that had once been my mother’s pride and joy.

The lake house, my lawyer told me later, looked smaller when it was empty.

Houses always do.

“They left it a mess,” she added, flipping through photos on her tablet. “Nail holes everywhere. Stains on the deck. And, uh, this.”

She zoomed in on a wall.

Someone—Caleb, judging by the handwriting—had written “SNITCHES GET STITCHES” in black marker near the back door.

I raised an eyebrow.

“Charming,” I said.

“You want to press vandalism charges?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “He’s thirteen. Let’s not turn him into a hardened criminal before he’s old enough to shave.”

I thought about that for a second and added, “Yet.”

We both laughed.

It felt good.

Months passed.

The lake house became another line item in my world. A property. An asset. I hired a contractor to repair the damage and repaint. I debated selling it, then decided against it.

For the first time ever, it wasn’t a symbol of obligation.

It was mine.

Maybe someday I’d take Leo there and show him a lake that didn’t echo with insults.

In the meantime, I focused on our little home.

Tuesday nights became pizza nights.

Just me and Leo at the kitchen table, a greasy cardboard box between us.

He always wanted half pepperoni, half plain. I always pretended I didn’t like the pepperoni so he could have more.

One night, maybe three months after the eviction, he held up a drawing.

“Look,” he said, grinning.

It was us.

Me and him, drawn with round heads and stick bodies, standing on top of a lopsided triangle mountain.

We were holding hands.

Above our heads, in green crayon, he’d written: ME AND MOM.

No Grandma. No Aunt Vanessa. No Caleb.

“Where are we?” I asked.

“On top,” he said.

“Of what?”

He thought for a second. “Of not being mean.”

I swallowed hard.

And there it was.

My return on investment.

The empty chairs at our table didn’t make the picture incomplete.

They made the picture possible.

People talk about empty chairs like they’re tragedies. Proof that you’ve failed to be loved, failed to keep your family together, failed as a daughter or sister or friend.

But the truth is, an empty chair can be a monument.

It’s the physical space where you decided your dignity mattered more than someone else’s comfort.

It’s a line in the sand that says: I would rather sit alone than sit with people who make me feel small.

An empty chair isn’t a void.

It’s a boundary.

It is a reserved seat for peace.

I took a bite of pizza.

It tasted like freedom.

I had audited my life.

I had liquidated the bad assets.

And for the first time in thirty-six years, I was solvent.

Financially.

Emotionally.

Relationally.

The books balanced.

The numbers finally told a story that added up.

I thought that was the end of it.

But life, like any good audit, likes to surprise you with a few unexpected line items down the road.

Part 4

Two years after I evicted my family, I ran into Caleb in the most predictable place in the world.

The mall.

Leo and I were in the food court like we were starring in a live-action cliché. He’d just turned nine and had saved up birthday money for a very specific pair of sneakers that, according to him, would make him run “like lightning.”

We ate greasy fries at a sticky table under flickering fluorescent lights. Leo was talking me through the pros and cons of neon laces versus white ones like he was presenting a case before the Supreme Court.

Then I heard it.

“Lena?”

A male voice, deeper than the last time I’d heard it, but still edged with the same entitled tone.

I turned.

Caleb stood there, a tray from Panda Express in his hands. He was taller now, shoulders broadening. The sharpness in his face had softened a little under a layer of adolescent awkwardness. He wore a faded hoodie instead of a blazer.

“Hey,” I said.

I didn’t say his name.

Let him do the work.

He shifted from foot to foot, eyes flicking between me and Leo, who had gone quiet.

“Hi, Aunt Lena,” he said finally.

The title sounded strange in his mouth.

Leo stared at his tray. At the orange chicken. At anything but Caleb.

“How’ve you been?” Caleb asked.

“Good,” I said. “Busy. You?”

He shrugged. “Fine.”

He glanced at Leo again and opened his mouth.

“Leo, I—”

Leo stood up suddenly.

“I’m going to throw this away,” he said, clutching his empty soda cup like it was a shield. He walked briskly toward the trash cans, shoulders rigid.

I watched him go.

Then I looked at Caleb.

“You don’t get to talk to him,” I said quietly.

He flinched.

“I just wanted to say sorry,” he mumbled.

“For what?” I asked.

He swallowed. “For… you know. What I said. That day. I was just being stupid. Mom said—”

“Stop,” I cut in. “I don’t need to hear your mother’s script. I’ve heard enough of her writing for a lifetime.”

He shifted again. “I wasn’t at St. Jude’s for long after… everything,” he said. “They, uh, kicked me out.”

“Zero tolerance policy?” I asked.

He gave a small, humorless laugh. “More like zero scholarship policy when the money stopped coming.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Ah.”

“My mom said it was your fault,” he added. “For a long time. She said you abandoned us.”

“That sounds like her,” I said.

“But then,” he went on, “I heard her talking to Grandma one night. They didn’t know I was listening. She was saying stuff like ‘Lena always thought she was better than us, with her spreadsheets and her rules’ and ‘she actually cut us off because of Caleb calling Leo trash, can you believe it?’”

He rubbed the back of his neck. “And Grandma laughed. Like it was funny. Like it was stupid that you’d pick Leo over them.”

“They’re very consistent,” I said.

“I realized…” He trailed off, searching for words. “I realized they didn’t think they did anything wrong. Like, not even a little. They were more mad at you for reacting than at me for saying it.”

I nodded. “That tracks.”

He glanced up at me, eyes bright with something I didn’t recognize on his face. Shame, maybe. Or understanding.

“I was a jerk,” he said. “I’m still… working on not being one. I started going to this after-school program at the Y. They make us, like, talk about stuff. Feelings and all that crap.”

“Feelings are not crap,” I said, but there was no heat in it.

He smirked faintly. “Yeah. That’s what they say, too.”

We stood there, two people connected by blood and debt and bad decisions neither of us had made on purpose.

“I don’t expect you to forgive me,” he said. “And I don’t expect Leo to. I just… wanted to say that I know what I did. And I know it hurt. And I’m sorry.”

It was not the kind of apology my family had trained me to expect.

No excuses. No “but you.” No “we were all under stress.”

Just a kid, standing in a food court, holding a tray of orange chicken, trying to be less like the adults who raised him.

“Thank you,” I said.

He nodded.

“I gotta go,” he muttered, shifting his tray. “My shift starts in ten.” He nodded toward the shoe store across the way. “Employee discount is twenty percent, if Leo likes anything there.”

I followed his gesture.

A few months earlier, that would have sent me into a spiral—thinking about the tuition I’d paid for his private education, the opportunities Leo didn’t get.

Now, it just felt like math.

“That’s generous,” I said. “We’re good today. But… thanks.”

He half-smiled. “Okay. Um. Bye.”

He walked away, shoulders hunched, disappearing into the crowd of teenagers and exhausted parents and people trying to sell cellphone cases.

Leo came back, trash disposed of.

He climbed into his chair and picked up a fry.

“Are we leaving?” he asked.

“In a minute,” I said.

He nodded.

“He apologized,” I added, keeping my tone casual. “For what he said.”

Leo chewed thoughtfully.

“Do you believe him?” he asked.

I thought about it.

“Yes,” I said. “I do.”

Leo wiped his fingers on a napkin. “Okay,” he said.

He didn’t say anything else. But when we walked past the shoe store fifteen minutes later and saw Caleb behind the counter, Leo didn’t hide behind my arm.

He didn’t wave, either.

He just walked. Head up.

That was enough.

Years rolled by.

The lake house became our place.

After the repairs were done, I started taking Leo there once a month. Just for a night or two. We’d fish off the dock and burn marshmallows over a fire pit and fall asleep to the sound of crickets instead of freeway hum.

The first time we went back, Leo stood on the deck for a long time.

“Do you remember what happened here?” I asked.

He nodded. “Sometimes,” he said. “But not all the time.”

“What do you remember now?” I asked.

He thought.

“Marshmallows,” he said. “And that weird frog noise at night. And how the stars look bigger here.”

“Those are good things to remember,” I said.

We went inside.

The dining table was different now. Smaller. Round. Just enough room for the two of us and maybe a couple of friends if we invited them.

I’d gotten rid of the long, rectangular monstrosity that used to host my mother’s elaborate dinners.

In its place was something modest. Solid.

We ate grilled cheese sandwiches on paper plates and played cards.

No one smirked.

No one called anyone trash.

The empty chairs that used to fill me with dread were gone.

Replaced by a table that fit the family I actually had.

Leo grew.

He joined the robotics club at school. Started reading everything he could get his hands on about coding and engineering. He’d sit at my dining table—our dining table—with his laptop open, muttering to himself about “debugging.”

When he was thirteen—Caleb’s age when all this began—he came home with a flyer.

“Mom,” he said, dropping his backpack by the door. “There’s this summer program. For engineering. At the community college.”

He handed me the paper. “It costs money,” he added quickly. “I can get a partial scholarship, but I need to write an essay. Do you think I can?”

I looked at the flyer.

Then I looked at my son.

Smart. Kind. Funny. Bruised by life, but not broken.

“Yes,” I said. “I think you can.”

He wrote the essay at the kitchen table, tongue poking out in concentration. I edited for grammar, but not for content. His voice was clear.

He got the scholarship.

The rest of the tuition?

I paid.

Happily.

Because this time, my money was an investment with a clear return: my child’s future, not someone else’s entitlement.

On the first day of the program, when I dropped him off at the community college, he turned in the passenger seat and looked at me.

“Mom?” he said.

“Yeah?”

“Do you… ever miss them?” he asked.

He didn’t have to specify.

I knew who he meant.

I took a breath.

“Sometimes I miss the idea of them,” I said. “The idea of having a grandma who bakes cookies and an aunt who shows up with gifts. I miss what I thought they were when I was little. But I don’t miss who they actually are.”

He nodded slowly.

“Do you?” I asked.

He considered.

“I kind of miss the lake sometimes,” he said. “From before. When it wasn’t… weird.”

“We made new memories there,” I reminded him. “Just us.”

He smiled. “Yeah. The frogs are still loud.”

We sat in silence for a moment.

“Do you think,” he asked quietly, “that you’ll ever forgive them?”

It was a fair question.

Forgiveness. That big, shiny word people toss at you like confetti at a parade you never signed up for.

“I forgive them for not being the people I wanted them to be,” I said slowly. “I forgive myself for taking so long to see it. But I don’t trust them. And I don’t want them in our lives.”

He nodded.

“That’s enough,” he said, unbuckling his seat belt. “See you at three?”

“I’ll be here,” I said.

He got out, backpack slung over one shoulder, and jogged toward the entrance.

I watched him go.

And I realized something.

The little girl inside me—the one who’d sat at my mother’s table, desperate for approval, calculating every word—had been evicted, too.

There was no room for her in this new ledger.

The only dependents on my emotional balance sheet were me and my son.

Everyone else?

Liabilities.

Written off.

Part 5

The last time I saw my mother, it wasn’t at a courtroom or a house or a hospital.

It was at the grocery store.

I was standing in the produce section, debating between organic and regular strawberries, when I heard a familiar laugh.

Sharp. Dismissive. A little too loud.

I turned.

Evelyn stood by the citrus display, complaining to a woman I vaguely recognized from the old neighborhood.

“…and then she just cut us off,” Mom was saying, her hand on her chest like she always did when she wanted people to see her as delicate. “No warning. No compassion. After everything I did for her. Kids these days, I swear. No sense of duty.”

She looked older.

Not frailer—she was still standing straight, still moving briskly—but the bitterness in her voice had carved new lines around her mouth.

The other woman clucked sympathetically. “That’s terrible, Evelyn. You deserved better.”

I felt something twist inside me.

Not guilt.

Not anger.

Just… sadness. Clean and small.

For her.

For the fact that she would likely live the rest of her life inside that story, never once considering that a different narrative might exist.

I could have walked away.

I almost did.

Then she turned—and saw me.

Our eyes met over the pile of oranges.

For a second, everything fell away. The years. The money. The smirks.

I was her daughter again.

She was my mother.

“Lena,” she said.

My name came out like a curse and a prayer and a question all at once.

“Hi, Mom,” I said.

The other woman looked between us, the realization dawning on her face.

“This is the one?” she asked Evelyn softly.

My mother straightened her shoulders.

“Yes,” she said. “This is the one.”

She didn’t say my name again.

Just the one.

As if that defined me more than anything else.

The daughter who cut her off.

The daughter who refused to finance another decade of emotional embezzlement.

The daughter who wrote off a bad investment before it took her under.

“Lena,” Mom repeated, recovering. “How have you been?”

“Good,” I said. “Busy.”

I could have told her about Leo’s engineering program. About his A in math. About his latest comic book obsession.

I didn’t.

“You look well,” she said.

“So do you,” I replied.

We stood there, separated by fruit and history, two people who shared DNA and almost nothing else.

“I heard you bought the lake house,” she said, eyes narrowing.

“I did,” I replied. “Technically, the bank sold it to me. I just paid the invoice.”

“And now what?” she demanded. “You sit up there alone? Thinking you’ve won?”

“I sit up there with my son,” I said. “Thinking I’m free.”

She scoffed.

“You’ll regret this someday,” she said. “When you’re old. When you’re sick. When you realize you pushed away the only people who ever really cared about you.”

Once, that would have gutted me.

Once, I would have replayed those words in my head at 2:00 a.m., cataloging every example of my alleged unlovability.

Now, I just shrugged.

“I didn’t push away people who cared,” I said. “I pushed away people who used me. There’s a difference.”

Her mouth thinned.

The other woman shifted awkwardly, murmured something about needing to check on frozen peas, and escaped.

“What did you expect me to do, Mom?” I asked quietly. “Keep paying for Caleb’s tuition while he called my son trash? Keep covering your wine bill while you smirked at my hurt? Where was your care then?”

“That was one moment,” she snapped.

“It was a mirror,” I said. “It showed me everything I needed to see.”

I picked up a carton of strawberries and put it in my cart.

“I hope you’re okay,” I added. “I don’t want you to suffer. I just don’t want to fund it.”

“You’re cruel,” she said.

“I’m solvent,” I replied.

We stared at each other for a heartbeat.

Then I pushed my cart toward the dairy aisle and left her there.

I thought I’d feel triumphant.

I didn’t.

I felt… finished.

Like a case closed. Like the last page in the file had been signed off on and sealed.

Later that night, Leo and I sat at our kitchen table, strawberries washed and piled in a bowl between us.

He was working on a science project.

“Mom?” he asked, without looking up from his poster board.

“Yeah?”

“Do we have any more glue sticks?”

“In the drawer,” I said, pointing.

He dug for them, found one, and started writing carefully: SIMPLE CIRCUIT DEMONSTRATION.

I watched him.

“Hey,” I said. “Can I tell you something?”

He glanced up. “Sure.”

“I saw Grandma today,” I said.

His hand paused.

“Oh,” he said. “Where?”

“Grocery store,” I said. “By the oranges.”

“What did she say?” he asked.

“That she thought I’d regret my decisions,” I said. “Someday. When I’m old and sick.”

He contemplated that.

“Do you?” he asked.

“Do I what?”

“Regret it?” he clarified.

I thought.

“There are things I regret,” I said slowly. “I regret not seeing things sooner. I regret how much money I spent trying to buy respect. I regret letting them hurt you as long as they did. But I don’t regret leaving.”

He nodded.

“I don’t either,” he said.

I blinked.

“You don’t?” I asked.

He shook his head. “I remember that night,” he said. “On the deck. I remember how it felt when no one said anything.”

He looked up at me.

“But I also remember when you stood up,” he said. “And took my hand. And just… left.”

He smiled.

“That part felt better,” he said.

I swallowed, suddenly very aware of the sting behind my eyes.

“Yeah?” I managed.

“Yeah,” he said simply. “It felt like… like you chose me.”

“I did,” I whispered.

He shrugged, going back to his poster. “Then I don’t care what she thinks,” he said. “I like it better now.”

The thing about audits is that they’re not just about catching fraud.

They’re about making sure what’s left is accurate. Honest. Real.

When I turned my skills on my own life, I found embezzlement where love should have been, exploitation where support had been advertised, and debt where there should’ve been a cushion.

I also found something I hadn’t accounted for.

Me.

My capacity to draw a line.

My willingness to step away from a loaded table.

My ability to build something new from the wreckage of something old.

If your family smirks while your child is being shredded, you have a choice.

You can flip the table.

You can scream.

You can plead.

Or you can do what I did.

Stand up, say nothing, take your child’s hand, and leave.

Then go home, open your books, and cut every line that funds your own destruction.

It will hurt.

You’ll grieve the imaginary people you tried to buy with real money.

You’ll stare at empty chairs and feel like a failure.

But one day—maybe at a pizza night, maybe at a mall, maybe at a kitchen table covered in glue sticks and poster board—you’ll realize those chairs aren’t empty anymore.

They’re full of something quiet and priceless.

Peace.

Safety.

Self-respect.

Solvency.

I used to think being a good daughter meant paying any price to stay at the table.

Now I know better.

I don’t need their table.

I’ve got my own.

And everyone who sits at it knows the first rule:

Trash doesn’t belong outside.

Trash doesn’t belong anywhere near us.

Trash doesn’t belong in my ledger.

We took it out.

We took ourselves out.

And what’s left?

That’s family.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

“Christmas Is Better Without You!” My Dad Texted I Replied With A Single Word Soon, Their Lawyer…

Returning home for Christmas in years—only to receive a brutal message from her own father: “Christmas is better without you….

My Sister Cut My Car’s Brake Lines To Make Me Crash, But The Police Call Revealed The Truth…

My Sister Cut My Car’s Brake Lines To Make Me Crash, But The Police Call Revealed The Truth… Part…

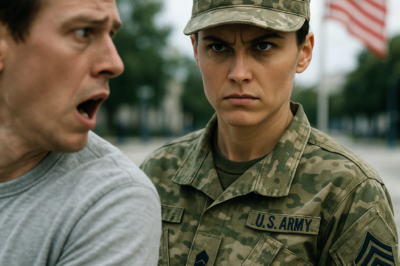

My Family Mocked Me for Years. Then the Man They Set Me Up With Ran From Me in Terror

She was just a quiet staff sergeant—until the man her family wanted her to date ran from her in terror….

We’re outnumbered the Marines shouted—Until a silent marksman above them dropped hostiles one by one

We’re outnumbered the Marines shouted—Until a silent marksman above them dropped hostiles one by one Part 1 The first…

She Offered Him a Ride as a Kindness — Only Later Learning the Single Dad Was a Navy SEAL Widower

She Offered Him a Ride as a Kindness — Only Later Learning the Single Dad Was a Navy SEAL Widower…

“You Don’t Deserve First Class,” He Smirked. Then TSA Froze When My ID Triggered Code Red.

They gave her the worst seat on the plane. They mocked her job, her looks, her silence. She Was Treated…

End of content

No more pages to load