My Nephew Mouthed, “Trash Belongs Outside.” Everyone Smirked. I Nodded, Took My Son’s Hand, and Left

Part I

Sunday dinner at my mother’s had become ritual long before Lauren installed her in the little apartment attached to her house. Mandatory wasn’t written anywhere, but it was understood—like taking off your shoes in winter, like saying grace even if you didn’t believe in anything. I showed up out of habit, out of some rusted sense of duty, and because my six-year-old son, Daniel, still believed me when I said family mattered.

Lauren’s husband, Greg, was at the grill, façade of competence intact while flames licked the chicken thighs he’d marinated in something sugary. Their three kids—twelve-year-old Connor and the nine-year-old twins—exploded around the backyard like firecrackers, a noise that made Daniel shrink closer to my hip. Mom was already supervising from the patio with her stemless glass of Chardonnay, dispensing correction the way a priest dispenses blessings.

“You’re late,” Lauren said when we walked in.

“It’s Sunday,” I answered, because the line always came and I always volleyed back. “There’s no traffic.”

Daniel’s hand tightened. He had never liked these dinners—the volume, the inertia of a family whose roles were set in concrete. “Go play,” I told him, trying to make my voice sound like an invitation, not an order. He slid toward the yard, orbiting the shouting children like a cautious moon.

Inside, I carried deli sides to the picnic table: potato salad sweating in its plastic tub, coleslaw collapsing into itself. Store-bought rolls that looked like forgiveness and tasted like air. It was the kind of dinner meant to look effortless, which is to say that a woman had put in a vow’s-worth of work to ensure it appeared that way.

“How’s work?” Mom asked, as though she were reading from a cue card.

“Busy. Good.”

“Still at the hospital?”

“Yes. Still managing the billing department.”

“That’s nice. Stable.” She made “stable” sound like “sedentary.”

Greg arrived with a platter of chicken. “Everyone hungry?”

The kids descended like locusts. Connor shouldered past Daniel to be first in line; the twins clambered over each other, elbowing insistently at the center. Daniel hesitated the way polite children hesitate when they notice, however dimly, that politeness is not how you get fed.

“Daniel, sit,” I said, guiding him to the chair beside me.

Connor snorted. “Why does he get to sit by the adults?”

“Because I’m his mother,” I said, “and I said so.”

“He should sit at the kids’ end. That’s where he belongs.”

“Connor, don’t be rude,” Lauren said, smiling. The smile was delicate as gold leaf and twice as useless.

We ate. The twins argued over whose teacher was meaner. Connor complained about math and the specific indignities of a twelve-year-old tyrant condemned to learn fractions. Greg talked about a promotion as though he’d already hung the new title on himself. Mom praised Lauren’s hosting, which meant the dishes looked expensive and she had remembered to chill the wine.

“How’s school, Daniel?” Mom asked, as if she’d almost forgotten there might be a quieter child at the table.

“Good,” he said softly. “I like reading.”

“Reading’s important,” she said, before swiveling back to the promotion talk. Daniel cut his chicken into minuscule squares and ate each one like a secret. He was the kind of boy who made way for other people without being asked, who said thank you even when no one noticed he’d been served.

After dinner, the kids flooded the yard again, and I stood to collect plates because it felt safer to move.

“Leave those,” Lauren said. “Greg will get them later.”

“I don’t mind,” I said.

“Leave them.”

I set the plates down and returned to my chair. Mom topped off her wine. Lauren checked her phone. Greg wandered inside with the single-mindedness of a man who hears sports calling him by name.

Through the window, Connor trapped the soccer ball under one foot. The twins chased him, flapping like birds. Daniel stood near the fence, hands at his sides, watching, trying to read the rules of a game that changed the second he understood it.

Connor sent a kick screaming toward the fence. The ball rebounded near Daniel.

“Get that!” Connor yelled.

Daniel picked it up and threw it back, tentative.

“You’re supposed to kick it, dummy,” Connor said, catching. “Don’t you know anything?”

The twins laughed. Daniel’s face darkened with a blot of shame, and he walked toward the house like a soldier who has seen the wrong kind of battle.

“Sensitive,” Lauren said, sipping water that might as well have been approval. “Kids need thicker skin.”

“He’s six,” I said. “Connor tougher at six?” I didn’t ask it as a question.

Connor barreled in for water and met Daniel’s eyes like they were a target.

“Why is he always so weird?” he asked, casual as a sigh.

“Connor,” I snapped.

“What? He is. He doesn’t play right. He doesn’t talk. He just stands there.”

“He’s shy.”

“He’s weird.”

He sloshed water into his bottle and left. Lauren didn’t correct him. Mom didn’t speak. A small theater of adults elected to let a child become a mirror for their meanness.

“He could be more social,” Mom said finally, like a judge issuing sentence. “Might help him make friends.”

“He has friends.”

“Does he? Lauren says Connor’s never seen him with anyone at school events.”

“Different grades. Different classes.”

“Still, a child should be more outgoing. Maybe some activities. Sports,” she said. “Something to toughen him up.”

I felt Daniel press into me like a plant seeking light. He heard every word; we teach children to absorb everything and then chide them for keeping account.

“He’s fine as he is,” I said.

“You’re too soft on him.” Mom’s voice gentled into something I recognized from childhood, a tone that always accompanied taking something away. “Boys need structure. Discipline. My generation knew how to raise strong boys.”

“Your generation also thought hitting kids built character.”

“Don’t be dramatic. I’m saying he could use some backbone.”

I stood. “Daniel, go get your jacket.”

“Already?” Lauren asked. “It’s not even seven.”

“We have things to do on a Sunday night.”

“Yes,” she said, incredulous, “like being sensitive.”

Daniel ran down the hall for his jacket. I reached for my purse.

“You’re being sensitive,” Mom said. “No one meant anything by it.”

“Connor called him weird twice. You said he needs to toughen up. Lauren called him sensitive. I’d say plenty was meant by it.”

“Boys tease each other,” Mom said. “It’s normal.”

“Except Connor’s your grandson,” I said. “And Daniel’s your grandson. And you only defended one of them.”

The doorway filled with Connor, his shoulders squared with the assurance of a boy who has never been told no by someone he respects. “Grandma, is Aunt Claire leaving because of me?”

“No, sweetie,” Mom said. “Your aunt is just—”

Connor looked at me. He raised his hand, pointed, and mouthed, with the slow precision of a surgeon: Trash belongs outside.

The twins clustered behind him, trying to stifle their laughter, failing. Lauren’s mouth made a shape like a gasp and then closed over it. Mom’s face registered surprise, then sawed it down to something neutral with one sip of wine. Greg, in the living room, whooped at a quarterback I could not see.

No one defended me. No one corrected Connor. No one told the twins to knock it off or told their son that words make shapes inside people that are hard to walk around. They let a twelve-year-old call me trash while my six-year-old stood in the hall with his jacket in his hands.

I nodded once. “You’re right,” I said—to no one and to everyone. “We should go.”

I took Daniel’s hand and we walked out into the remaining light.

He was too quiet in the car. The quiet of a child who has learned the world can be mean to his mother.

“You okay, buddy?”

“Why did Connor say that about you?”

“Because he’s twelve,” I said, “and he doesn’t understand how words hurt. Not yet.”

“But nobody told him to stop.”

“I know.”

“Grandma didn’t say anything.”

“I know.”

“Does that mean they think you’re trash too?”

“What they think,” I said, “doesn’t matter.”

“Does it matter what I think?”

“Very much,” I said. “What do you think?”

“I think you’re the best mom and they’re mean.”

“Thank you,” I said. “That’s all that matters.”

At home, we fell into our nightly choreography. Bath, pajamas, toothpaste foam like a cloud he tried to show me in the mirror. Two stories. His favorite stuffed bear tucked under his chin. The room burrowed into darkness like a glove.

In the living room, I sank into the couch with my phone and opened my banking app. The monthly transfer was due—the same as it had been every month for seven years. Three thousand two hundred dollars to my mother’s account. I’d set it up when she retired early, citing health issues and the exhaustion of a life that had asked too much. “Just for a while,” she’d said. “Until I get back on my feet.”

Seven years later, she was on her feet—on a patio, with wine, watching her grandson call me trash by proxy.

I scrolled through the ledger: eighty-four payments. Two hundred sixty-eight thousand, eight hundred dollars, not counting extras. There were the doctor bills; the car I co-signed for; the furniture; the hearing aids; the dental work. I could tally it like a crime: probably three hundred thousand, counting the invisible parts—the afternoons I left work early to handle calls, the hours I spent pricing prescriptions, the birthdays I buoyed with “extras.” A life built on a promise that when the family card was played, I would always be the one to pay.

The phone buzzed. A new text from Mom: monthly transfer today.

Just that. No mention of Connor. No apology. No acknowledgment. Just the expectation of money summoned like a house pet.

I typed three words: Not my concern.

Then I paused, watched my own breath, and pressed send. With my thumb still warm, I canceled the automatic transfer, deleted Mom’s account from my saved recipients, and closed the app.

I opened my laptop. If the world would insist that I turn a family into numbers, then I would oblige with accuracy. I built a document like a scaffold and began to itemize every payment, every transfer, every bill I covered. I attached PDFs that proved I was the financial guarantor on her medical statements. I added the car loan documents with my name awkwardly tethered to hers. Receipts for furniture, appliances, hearing aids—the paper bones of a comfortable retirement that had arrived not by luck or pension but by the daughter whose son had just been taught a lesson about his mother’s value.

I saved the document. I powered down. I stood in the doorway to Daniel’s room and listened to the soft animal of his breathing and wondered how so much of a life is spent learning what you don’t have to endure.

Part II

On Monday morning, before the hospital coffee could turn from bitter to merely hot, I sent the email. Not just to Mom. To Lauren and Greg. To my brother, Kevin, who lived out of state and called on holidays to collect his portion of credit for loving a family he rarely saw.

Subject: Financial support documentation 2017–2024.

The body was clean, surgical. Please find complete documentation of financial support provided to Patricia Brennan from November 2017 through November 2024. This includes monthly transfers of $3,200, medical expenses, co-signed loans, and miscellaneous expenses. Total support provided: approximately $268,800 in direct transfers, plus additional costs, estimated $300,000 in total. Effective immediately, all support ceases. Monthly transfers canceled. Co-signed obligations: I am pursuing removal as co-signer through refinancing requirements. Medical guarantor status will be revoked with 30 days’ notice to providers. Mom’s current monthly expenses: rent—zero (lives with Lauren); car payment—$412 (co-signed by me); car insurance—$128; health insurance supplement—$360; utilities—approx. $150; food and incidentals—approx. $500. Total monthly expenses—approx. $1,550. Mom’s monthly income: Social Security—$1,042; pension—$618. Total—$1,660. The math works. This decision is final and not open to discussion or negotiation.

I signed it and hit send.

By nine o’clock, my phone rang. I let it.

By ten, seventeen text messages waited like a pile of unpaid tickets. Mom: We need to talk. Lauren: What is this? You can’t just stop supporting Mom. Kevin: This is insane. Call me immediately. Greg: Let’s be reasonable about this. Lauren again: Mom is crying. You’re being cruel. Mom again: Please call me. We can work this out.

I answered none of them. I revised a spreadsheet for work, filed an appeal for a patient’s denied claim, and took a call from a surgeon who wanted to know why he’d been reimbursed a nickel less than he believed himself owed. It turned out you could move through a day touching five different versions of entitlement and keep your voice steady for all of them.

At noon, Kevin called from Oregon. I answered this one. He barked into the line without a hello. “Have you lost your mind?”

“No,” I said. “I’ve regained it.”

“You can’t just cut Mom off.”

“I didn’t cut her off. I stopped funding her optional lifestyle expenses.”

“She can’t survive on sixteen hundred a month.”

“According to my math, she has exactly thirty dollars left over. That’s called a balanced budget.”

“What about emergencies?”

“I’ve handled seven years of emergencies,” I said, heat rising. “Your turn.”

“I have my own family.”

“So do I,” I said. “A son who watched his grandmother sit quietly while his cousin called me trash.”

There was a moment where the phone turned ocean-silent. “Connor really said that?”

“He mouthed it,” I said, “and everyone saw. No one corrected him. No one pulled him aside. Daniel stood in the hallway holding his jacket while adults smirked and a boy learned who it’s safe to be cruel to.”

“That’s not okay,” he said eventually.

“No,” I said. “It’s not. And when I stopped funding the people who thought it was okay, suddenly everyone wants to talk about what’s reasonable.”

“So you’re cutting everyone off?”

“I’m cutting off the money,” I said. “They cut me off when they smirked at a child calling me trash.”

After Kevin came Lauren, then Greg, then Mom again. Voicemails stacked like plates at the end of a party no one wanted to clean up. That afternoon, the hospital swallowed me until five, and the motions of my job steadied the swinging chandelier of my temper. Numbers behave even when people don’t.

On Tuesday morning, the car lender called. “We’re reaching out to the co-signer,” the representative said. “A payment was missed.”

“I’m pursuing removal as co-signer,” I said. “The borrower has sufficient income to cover payments. I’m no longer willing to guarantee this loan.”

She was polite as she explained the process, a courtesy that surprised me into gratitude. Mom would need to refinance on her own. If she couldn’t qualify, she would have to surrender the vehicle. Even politeness is a kind of weather; in it, I felt myself unclenching.

That afternoon, Lauren came to my house unannounced. She didn’t get far. I kept the screen door between us.

“Mom’s panicking,” she said, breath fogging the mesh.

“That’s unfortunate,” I said.

“Claire, be reasonable. She needs that money.”

“She needs to live within her means,” I said. “She’s seventy-two. I’m thirty-eight. I have a child to raise.”

“A child your son called trash,” I added, because avoidance is a seduction and I didn’t intend to let it woo me.

“Connor was just being stupid.”

“And you were silent,” I said. “Which is worse.”

“I didn’t know what to say.”

“How about ‘Connor, that’s unacceptable’? How about ‘Apologize right now’? How about anything other than that little smile you wear when cruelty aligns with your comfort?”

“I wasn’t smirking,” she said.

“You were smiling,” I said. “I saw it.”

She swallowed and glanced at the driveway as if an answer might be idling there with the engine on. “What about Mom? She’ll lose everything.”

“She’ll lose the car she barely drives,” I said. “She’ll lose the premium cable package I didn’t know I was paying for. She’ll lose the wine budget. She’ll still have a roof over her head in your apartment. She’ll still have food. She’ll still have healthcare. She’ll be fine.”

“This is selfish,” Lauren said. “You’re punishing everyone for one mistake.”

“This is self-preservation,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

She blew out a breath, the sound an old sibling argument recognizes. “I don’t know who you are right now.”

“I do,” I said, and closed the inner door slowly enough to be kind.

On Wednesday, Mom called from Lauren’s phone. I answered. I wanted to hear the voice that had learned to be silent when the wind blew in the direction of her favorite child.

“Please,” she said, and for a second her voice was young, my mother before the disappointments settled into her posture. “I’m sorry. Connor was wrong. I should have said something.”

“Yes,” I said, not rescuing her. “You should have.”

“But cutting off all support, that’s so extreme.”

“Is it more extreme,” I asked, “than watching your grandson call me trash?”

“He didn’t call you trash,” she said, defaulting to the precise line where deniability blooms. “He said ‘trash belongs outside’ while pointing at you. It’s not the same.”

“What else does that mean?” I asked. “He’s a child who learned that behavior from the adults around him—who learned that Claire is less than; that it’s okay to insult her because she’ll keep paying anyway.”

“That’s not—” she started.

“You didn’t have to use words,” I said. “You taught it by never defending me, by always taking Lauren’s side, by accepting my money while treating me like an obligation instead of a daughter.”

“I love you,” she said, the sentence so well-worn it was nearly threadbare.

“Love isn’t about words,” I said. “It’s about actions. Your actions told me I’m worth three thousand dollars a month—but not worth defending. So now you get neither the money nor the performance of pretending you value me.”

“What can I do to fix this?” she asked, hope tiny and brave in her voice.

“Nothing,” I said. “It’s not fixable with an apology seven years too late. It’s not fixable with promises to do better. It’s done.”

“Please, Claire. I’m your mother, and Daniel is your grandson.”

“The one you watched being hurt,” I said, “and said nothing. I’m protecting him now, the way you should have protected me then.”

I hung up. The silence after wasn’t empty; it had shape, like a room I could finally move in.

On Thursday, I took Daniel to school and found myself looking longer at the families that swelled through the doors. The father with a coffee stain on his cuff bending to tie his daughter’s shoelace. The mother carrying a toddler who slept with his mouth unselfconsciously open. I had always envied the fluorescent clarity of other people’s lives. That morning, I realized it was an illusion like any other. Everyone is performing, I thought. The question is for whom.

When I picked Daniel up that afternoon, he was smiling with his whole face.

“Good day?” I asked.

“Really good,” he said. “I didn’t think about Sunday at all.”

“That’s wonderful,” I said, and meant it. A child forgetting a hurt is a kind of miracle. “Are we still going to Grandma’s for dinner?”

“No.”

“For a while?” he asked.

“For a while,” I said, and when his shoulders loosened I felt the world tilt into its new alignment.

“Good,” he said. “I didn’t like them anyway.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked.

“Because you said family was important,” he said. “I didn’t want to make you sad.”

“Family is important,” I said. “But we get to choose what it means. It doesn’t mean spending time with people who hurt us. Even if they’re related. Especially if they’re related.”

“Okay,” he said. “Can we have our own Sunday dinners? Just us?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “What do you want to eat?”

“Pizza,” he said solemnly. “And we can watch movies and nobody will call us weird.”

“Perfect,” I said, and in the parking lot, his small hand found mine like it always had, and I felt the old litany of compromise unbraid inside me.

Part III

The first Sunday after the cut was ordinary on purpose. We ordered pizza from a place run by a man who had memorized our usual. We watched two movies—animated animals that knew more about loyalty than most people—and then played a board game where you roll your way through a forest, collecting kindness like treasure. We laughed without checking who was listening. The house held our sound gently instead of the way Lauren’s house threw every voice up to the rafters like a dare.

I didn’t check my phone. I didn’t fill a silence with a call to my mother. When Daniel went to bed, I stood in the kitchen, looking at the empty counter and the pizza box we’d folded into itself, and realized that peace doesn’t look like fireworks; it looks like not flinching.

On Monday—the eighth day since I’d stopped the transfer—I checked my phone during lunch. There were messages, but none about money. It seemed the math worked even without me, that life found its level like water does. The lender had followed up with paperwork for the co-signer removal; I printed it at work and signed my name cleanly, as if this time my signature belonged to me.

Kevin called again that afternoon, this time less angry. “I talked to Mom,” he said. “She’s… okay.”

“I’m glad,” I said.

“She misses you,” he added.

“She misses my money,” I said, and then felt the meanness of it bite me. “Maybe she misses me, too,” I adjusted. “But missing is not the same as valuing.”

“Can you two meet?” he asked. “Just talk? No money involved.”

“Not yet,” I said. “Maybe not ever. I’m not punishing her. I’m protecting myself. And Daniel.”

“I get that,” he said, cautiously. “I didn’t before. But I do now.”

“Good,” I said, the word strange and warm between us. “Then you can help her. That’s what sons do.”

He laughed a little. “So the prodigal finally gets a job.”

We hung up better than we had started.

On Tuesday night, Lauren texted a picture of the twins in their soccer uniforms, cheeks flushed, hair sticking to their foreheads. It was accompanied by: They miss Daniel.

I looked at the screen a long time. The twins were not unkind; they were nine and learning the rules everyone else played by. But I could not return them to a house where they would learn the wrong probability—that cruelty pays. I typed: Daniel’s doing well. Hope the game was fun. Then I put the phone face down and stood by the open window until the night had cooled my cheeks.

On Wednesday, Mom left a voicemail. Her voice had lost its courtroom air. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I am. I thought it was easier not to make a scene. I thought you were strong enough not to need me to speak. That was my excuse, and excuses are trash. I should have defended you. I should have told Connor to apologize. I didn’t, and I am sorry.”

I sat on the edge of the tub while Daniel took his bath and listened to the message twice. The sadness in it was real. The understanding in it was partial. I didn’t call back. Not because I wanted her to suffer but because a woman can break her own heart by letting the past rewrite itself too easily.

Thursday brought the lender’s decision: Mom did not qualify to refinance alone. She would need to surrender the car or find another co-signer. I declined to be interviewed for the role.

At work, Allison from HR asked me in the break room, “You okay? You look… taller, somehow.”

“I stopped apologizing for existing,” I said.

“That’ll do it,” she said, and we split a granola bar like communion.

By Friday, the hospital felt less like a battlefield and more like a place where I was useful. I stayed late to finish a report, not because I had to but because I wanted to. On my way out, I caught my reflection in the glass doors—hair pulled back, badge crooked, eyes awake. I recognized her, the woman in the reflection, in a way I hadn’t in a long time.

On Saturday morning, Daniel and I went to the farmers’ market. He picked out apples the way he picked friends—one at a time, with deliberation, because he intended to keep them. We sampled a cheese that smelled like a brave decision and bought a loaf of bread so fresh it scalded our fingers. We ate on the curb and watched a man play a violin with the practiced grief of someone who had survived loving and being left.

“Mom?” Daniel asked, crumbs dusting his lips.

“Yeah, buddy?”

“What does ‘trash belongs outside’ mean?”

I felt the air still. Honesty is a gathering you host for your child even when you don’t feel ready to greet it. “Trash is the stuff you throw away,” I said. “The things you don’t want in your house.”

“Are you trash?”

“No,” I said. “I’m something we keep.”

“Then why did he say it?”

“Because sometimes,” I said, “people try to make other people small so they can feel big. Or because no one taught them better. Or because being mean is easier than being thoughtful. But we get to decide whose words we keep.”

He nodded as if I’d given him a tool and he was already building with it.

That night, when I took the garbage out to the curb, I thought of the sentence he’d asked about and whispered to the cans, “You belong out here.” Then I closed the lid with a satisfying thud and walked back into my house where I belonged.

Part IV

On the second Sunday pizza night, Daniel declared himself head chef. He wore an apron I hadn’t known we owned and arranged toppings with the gravitas of an artist. He placed pepperoni as if mapping a small red planet, scattered olives like comets, and asked if we could make half with extra mushrooms “because some people like quiet flavors.” We ate on the living room floor and built a fort out of blankets, and he read me a story in a voice he only used when he forgot to be shy.

The doorbell rang once, then a second time. We froze like animals hearing thunder. I looked through the peephole. Mom stood on the porch alone, hands clasped around a paper bag.

I opened the door as far as the chain would allow. Boundaries are not spite; they are architecture.

“Hi,” she said. “I brought lasagna.” She held up the bag like a white flag with sauce on it.

“We just ate,” I said. My voice surprised me; it held more compassion than I expected, and also more steel.

“Can we talk a minute?” she asked. “No money talk. I promise.”

“Daniel,” I called over my shoulder, “go finish the movie. I’ll be right there.”

He nodded and scooted back into the fort, as if fort walls obeyed the laws of hearts.

I stepped onto the porch and closed the door behind me. The evening had cooled, and the sky wore the first stars like pins.

“I’m not here to ask for anything,” Mom said quickly. “I wanted to say sorry, not as a mother who’s embarrassed, but as a woman who should have been braver.”

I waited.

“I watched my grandson be cruel because I thought you didn’t need me to make a fuss,” she said. “I told myself you were strong. I told myself not to embarrass Lauren. I told myself a story where my silence was kindness. It wasn’t. It was cowardice dressed as calm.”

A swallow landed on the wire above us and made the smallest sound, like agreement.

“I won’t ask you to forgive me tonight,” she said. “I’m asking if I can try to be different.”

“Being different,” I said, “starts when it’s hard. Not when it’s convenient.”

She nodded. “I’ve talked to Connor,” she said. “He apologized.”

“Did he apologize to me?” I asked.

“Not yet,” she said. “I told him he needs to. He’s twelve, and I am his grandmother, and I forgot what that should mean.”

“Good,” I said.

“I also talked to Lauren,” she added, wincing. “We fought. The kind where you say the true thing and then the true thing says you back. She thinks I’m choosing you. I told her I am choosing right.”

I looked at the shape of my mother’s face, at the lines carved there by worry and wine and the years she spent guarding the doorway between herself and honesty. I felt something in me loosen, not forgiveness exactly, but a release of the idea that the past could be edited.

“You can try,” I said. “But trying doesn’t earn you access. You show up for me and for Daniel when it’s hard. You correct the people you love when they are wrong, even if they love you less after. You stop asking me for money while telling me I’m sensitive.”

She nodded again, slower. “I can do that,” she said. “Or I can try to. And I will fail, because I am me, but I will not fail the same way.”

“Okay,” I said, and for the first time in a long while, the okay meant we both understood the terms.

She shifted the bag. “Can I at least give you the lasagna?” she asked, a half-smile breaking like sun through a cheap blind.

“Leave it on the steps,” I said. “We’ll eat it tomorrow.”

She set it down and looked up at me with the nakedness people reserve for nurses and confessors. “I love you,” she said, and this time it was not a line. It was a risk.

“I know,” I said. “I love you too. I just love us more when we are safe.”

She turned to go. At the end of the walkway, she looked back the way people do when they are trying to memorize a house. I raised a hand. She raised hers. Then she went.

Inside, Daniel had paused the movie. “Is everything okay?” he asked.

“Everything is honest,” I said. “That’s better than okay.”

He nodded and offered me a blanket corner, and we finished the movie together inside the fortress we’d built ourselves.

A week later, I woke before my alarm and sat in the living room with the window open. The street was quiet, dew making the world look like it had been forgiven. My phone lay on the coffee table, black-faced and harmless. No messages from Mom about money. No guilt wrapped in obligations. The lender had collected the car; Lauren had driven Mom to the store without complaint because, apparently, people can adjust when they have to. Kevin texted a photo of his son wearing a Halloween costume that made him look like a triumphant banana.

I brewed coffee and packed Daniel’s lunch with the care I used to reserve for people who never said thank you. He wandered into the kitchen with his hair standing up like he’d been struck by a pleasant thought.

“Morning,” he said.

“Morning,” I said. “PB&J okay?”

“Perfect,” he said, and then, after a pause, “Can we invite Grandma to one of our Sunday dinners someday?”

I looked at him, at the boy who asked for pizza and gentleness with the same voice. “Maybe,” I said. “If she learns our rules.”

“What are our rules?”

“Kindness is mandatory,” I said. “Apologies count but don’t erase. Love is decided by actions. And we don’t let anyone call us names, not even in a joke.”

“Okay,” he said. “Can we add one? Extra mushrooms on half?”

I laughed. “Absolutely.”

We walked to school, and the light did that forgiving thing it does when you’ve finally told the truth. At the crosswalk, he squeezed my hand just once, a pulse of connection that said he saw me and I saw him and the world could be complicated and still be ours.

At work, I submitted the final paperwork to remove myself as a medical guarantor and updated Mom’s providers with her new billing information. I wrote an email to HR volunteering for a committee because suddenly I had space for a new problem that wasn’t my family. I ate lunch at my desk and watched a video of a man teaching his dog to fail gracefully, rewarding her for the attempt.

On the third Sunday, Daniel and I set the table with mismatched plates and lit two candles just to feel fancy. I texted Mom a picture of the table and the caption: We’re having dinner. No invitation. Just a window.

She replied with a heart and then, a moment later, wrote: Proud of you.

“Who was that?” Daniel asked.

“Grandma,” I said.

“What’d she say?”

“That she’s proud.”

“Of who?”

“Of us,” I said. And I realized that for once, I was proud of us, too.

We ate. We told each other the smallest stories of our week as if they were worth telling. Daniel asked if he could try the olives again and then decided he would like them in the future but not today. After we stacked the dishes, we stood at the sink, my hands in the suds, his hands ferrying rinse-wet plates to the rack.

“Hey, Mom?” he said, in that voice that means he’s about to tell me something true. “I don’t think about Sunday anymore.”

“Me neither,” I said.

He nodded like a judge handing down a merciful sentence. “Good.”

We turned out the kitchen light and the house blinked back at us, gentle as a blink can be. I tucked him into bed and read one chapter and then another because the chapter breaks were placed by cowards. He drifted off mid-sentence, a smile softening at the edges of his mouth.

I stood in the doorway of his room and listened to the life I wanted. I thought of Connor, of the twins, of Lauren and Greg and Mom, and all the ways we had rehearsed the wrong play for years. I thought of a boy who mouthed a cruelty because he’d been allowed to practice it and of a woman who didn’t correct him because silence had always paid better than courage. Then I thought of a woman who finally learned to drag the trash to the curb and a child learning that home is a place where you are never disposable.

On Monday—the fourteenth day since I stopped the transfer—I checked my phone again and found nothing urgent, which felt like a privilege. I dressed for work. Daniel pulled on his backpack. We walked out the door and locked it behind us, and the lock clicked with a clarity that sounded like a vow.

We were not late. We were not apologizing. We were not waiting for permission from anyone who had shown they would not grant it.

We were walking toward a day we had chosen.

Daniel and I were finally free.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

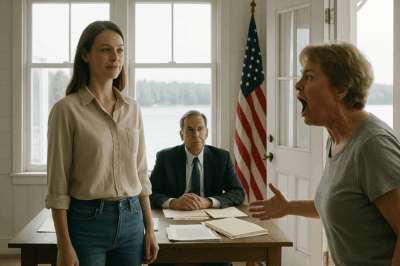

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

CH2. “Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp

“Wait, Who Is She?” — SEAL Commander Freezes When He Sees Her Tattoo At Bootcamp Part I — The…

CH2. Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL.

Four Recruits Surrounded Her in the Mess Hall — 45 Seconds Later, They Realized She Was a Navy SEAL …

End of content

No more pages to load