Part 1

Hello my friends, I’m not really sure how to get started. But I had something exceptionally bizarre happen to me. I’ve told a few people in my life, and usually the response I get is something along the lines of “that’s pretty friggin weird” or “oh, uh okay.” Anyway I’m not really sure what to do with this experience. You see movies or read stories and expect a pay off or crescendo or something of that nature whenever something big happens, but real life has a way of not caring for your resolution. Anyway, I apologize for rambling and I will just get started.

My story begins when I was 19 years old. Just a kid really, doing dumb shit that kids do. I had this neighbor, Mr. Onyxdragons. He had a really cool name, I remember thinking it was the coolest name I’d ever heard. Unfortunately Mr. Onyxdragons was just a regular old man. He didn’t do anything out of the ordinary, didn’t look or act strange, he didn’t seem to be hiding any secrets. No matter how much I wanted him to contain some mystery.

That’s the memory that keeps returning, like a rubber band snapping the soft flesh of the wrist: the name that didn’t fit the man. “Onyxdragons.” If your mouth is a skate park, that surname is the half-pipe—the way it pitches your tongue up, then down, then leaves you cruising on the long flat. The mailboxes in our neighborhood were dull blue metal; his forced the postman to write the syllables in extra-neat block letters, as if good penmanship could tame the absurdity. It made the rest of our cul-de-sac look like it was pretending. There was Baker, Sanchez, Kim, Reynolds, and then—like some fantasy author lost his place in the manuscript—ONYXDRAGONS.

But he himself? Beige in a cardigan. He mowed at the same time every Saturday. He watered the lawn until the hose sighed. He wheeled his trash bins to the curb in a neat diagonal, like a teacher arranging quiet children for a photo. If you waved, he’d give you a two-finger salute and a smile that never quite showed teeth. Nothing sparkled behind the glasses; there were no rings, no tattoos half-hidden by rolled sleeves, no odd visitors, no wild music at 3 a.m. Every mystery I tried to award him bounced off that polite surface and lay in the grass, embarrassed.

My dad knew him better. Not in the deep way—people in our town didn’t know each other like that—but in the routine way men on adjacent properties know one another: who borrowed whose ladder, who knew the best garage for brake pads, who silently agreed to take the first pass with a shovel when the snowplow piled a churned wall at the mouth of the street. My dad said he’d been a machinist once, then a custodian at the middle school, then retired. “Nice guy. Keeps to himself,” Dad said. Like a stamp. Like a verdict.

So when he passed away it was just as uninteresting as he was. It was sad, and unfortunate. He had gone to the hospital and had pneumonia and simply died. I learned about it from my dad who knew him a bit better than I did. No cool death or anything else that I am shallow enough to imagine. I remember feeling like an asshole when I caught myself thinking “imagine having such a cool last name and utterly wasting it on being boring.” It was a weird fixation I know, and for what it’s worth I felt like a piece of shit for even thinking it.

We didn’t go to a funeral, because there wasn’t one—at least not one we heard about. The ambulance lights washed over the windows one cold evening and then the house went back to the same unread page it had always been. A county van idled in his driveway for a while; two people went in and came out with a clipboard, looking puzzled rather than grief-struck. After that, silence. The curtains stayed shut. The grass kept being the correct length. In the green garbage bin every Wednesday, a black bag would appear like a magician’s bouquet and then disappear by afternoon.

Months went by after his death and I assumed that he would’ve had someone come by to clean it out, family or the government or whoever. But no one ever did. The house just sat there. The lawn remained maintained, everything looked in order. I had no idea who was taking care of the house, but someone was. The strange thing though is that I never saw anybody there. Believe me I kept an eye out for it too.

My summer got stale. I was nineteen and living at home to save money while I knocked out gen-eds at the community college. When I wasn’t at the warehouse loading trucks I was on the couch, half-playing video games, half-thinking about not being the person I had become by accident. There’s a restlessness that’s not quite energy—it’s more like the itch of a bandage under a shirt. I tried to scratch it with stupid things: late-night drives, drinking warm beers at the reservoir with people I only liked after midnight, texting exes who were smarter than me and knew to leave me on read. But the itch stayed.

And then there was that blue mailbox with ONYXDRAGONS in white vinyl letters, beginning to peel at the edges like something trying to molt. I found myself planning routes past it. The name glowed in my head like a neon sign left on in an empty bar. I imagined short stories where he was a retired war hero who’d faked his own death, or a magician in the witness protection program. I pictured hidden rooms and a secret library where the books hissed when you opened them. I pictured a dragon—ridiculous, but yes—sleeping in the crawlspace, coiled around the foundation, warming the water heater with its breath. I didn’t believe any of this. But I wanted it.

The more ordinary my days felt, the more offensive his plainness became to me, which is cruel, and which I regret. The problem with being nineteen—okay, one of the problems—is that you think names matter more than people. You think you can conjure a world from a word. You don’t realize that sometimes the most astonishing thing about a person is how quietly they carried their life across a floor.

Then August slid its hot thumb down the spine of the days and turned the page. I brought my dad coffee every morning before his shift, watched him stretch his back with a grimace that he thought I couldn’t see, and felt the future like an unmarked envelope I didn’t quite have the nerve to open. Something had to happen. Something dumb, probably.

One day I decided enough was enough, for no particular reason I decided to break into his house. I don’t really know why I did. I suppose it just bothered me the way it sat there seemingly frozen in time. The truth is he bothered me. Despite the irrationality of it all I could not stop thinking about him. How is your name Stormhawk Umber Onyxdragons and you don’t have any sort of interesting qualities to you? I feel like if my parents had given me such a name I would either feel compelled to do something crazy like becoming a navy SEAL or something badass. I feel crazy to even acknowledge how much it bothers me. I know it’s silly.

I wish I could claim a higher motive. I wish I could say concern tugged me across the strip of lawn, or that I heard a noise and thought an animal was trapped inside. The truth is my curiosity had curdled into something else. Envy, maybe. Or a dare to the world. If I cracked this house and found nothing, then fine: I would accept the universe’s commitment to beige. But if there was a hint of something—if there was even a good story to tell later—the itch might settle. I might stop seeing the name every time I closed my eyes.

It was a Tuesday at noon. The sky had done that high white thing it does in late summer, the heat rising without drama, as if it were just one more polite thing the day had to accomplish. I put on gloves because I didn’t want to leave prints—that part embarrasses me now; it assumes there would be consequences—and walked down the driveway whistling, like a person who belongs where he is. The front door had two locks and a peephole with a glass bubble like a fish eye. I didn’t try it. I went around back.

We had once returned a misdelivered package to his porch, and I remembered a loose slat in the fence. The gate stuck when you tried to open it properly but yielded if you lifted and pulled. I’d seen him do it. I did it. The yard was librarian-tidy. The pavers were free of weeds. The birdbath was full, a glassy circle with a single leaf sitting in it like a toy boat. The back window over the low couch—tan cushions, thin beige curtains—had a latch, and the latch, to my astonishment, was not snug against the frame.

Breaking in was easy enough. I didn’t even have to break anything really. I simply went around the back of his house, found a window that was unlocked, I managed to open it and crawl inside. I broke in during the day when everyone was at work, and I didn’t want to use any unnecessary electricity or anything, I didn’t know if the electric company would notice and investigate or not. Upon entering his house I landed in what looked like a regular living room, I got up and began looking around.

I stood there, one knee on the couch, palms full of a house that breathed as softly as a sleeping animal, and my brain, finally, went quiet.

Even now, remembering that moment, I can place the exact position of the dust in the light. I can recall the smell—powder and cedar and something else, a sweetness like the inside of a dry envelope. The air felt treated somehow, as if it had been taught the rules for how to exist in a proper home. Nothing was dirty. Nothing was excited. Nothing seemed surprised to see me.

I waited to be guilty. It didn’t arrive. I climbed off the couch and set my feet carefully on the beige rug. From the corner window I could see our own roofline and the vinegar bottle on our kitchen sill. The world looked thinner from here, as if I’d stepped behind the backdrop of a play and was now peeking through a slit at the audience. The refrigerator hummed like a polite throat-clearing. The clock over the mantel moved its hands without sound.

“Okay,” I said, to no one in particular. I rubbed my gloved fingers together and started to look around.

Part 2

Much to my great disappointment, his house was as boring as he was. In fact even so much to the point that his house was unsettling in a weird way. Everything was too nice, like it was a life sized dollhouse. Everything looked like it was just a large toy version of whatever it was supposed to be. I approached the couch that I would’ve sworn was made of plastic by looking at it, but when I approached it and touched it the strangest dissonance came over me. It was the most comfortable couch I’d ever felt in my life. Somehow the disconnect was enough to jar me, but not deter me.

I began searching his drawers and what not, but strangely enough everything was empty. No drawer or cabinet had a single thing. No dish ware, no random odds and ends that seem to pile up in drawers. All of the books were solid objects, they didn’t even open. They were just decorations. I was so confused at what this was that I didn’t even know how to feel. Creeped out? Interested? Even now I’m still not sure which.

I thought maybe I should leave, but I also figured that I was just being paranoid. What in the world could plastic do to me? As I picked up one of the plastic books to return it to its spot the strangest thing happened. It was so subtle I didn’t even really register it at the time. I felt a sense of accomplishment, similar to when you finish reading a book. I caught myself thinking about the premise of The Old Man and The Sea. The struggle that ends in futility. But then I remembered, I’d never read that book. I shivered and shrugged it off. Probably just some lecture I had heard at school or something.

The way this house worked wasn’t like other houses. I felt it then, and later I knew it. It was built from a blueprint that knew what humans expected and then shaved a millimeter away from every expectation. The plates in the cabinet were not plates; they were porcelain discs set into grooves, unremovable, the good dishes you never used, the ones you told yourself might matter when company came. The drawers were hollow diaphragms that sighed politely when you pulled them but contained nothing, because nothing messy was allowed. The television was a black rectangle that reflected your face and would never, ever turn on. The remotes had no batteries because there was nowhere for batteries to go; the backs did not open, like the bellies of mannequins.

The photos on the wall were the worst. They were not Mr. Onyxdragons’s family. They were stock human scenes printed on luminous paper: a boy holding a kite that had never flown; a woman in a meadow whose hair couldn’t possibly have landed quite that way without glue; an old man at the head of a rustic table that looked like IKEA’s idea of history. In the corner of one frame, I could just make out the ghost of a watermark, cropped with near-professional care but not entirely removed. I stared into the eyes of these fake people and felt, for the first time, as if I had broken into a set.

And then there was the sound, or lack of it. A real house ticks and creaks and burps; it confesses itself in small embarrassments. This one made only the noises of intention: the refrigerator hum, the clock that moved without sound, the faintest whisper of air that didn’t seem to come from a vent. I rubbed my arms although the temperature was fine. The comfort was a costume.

I thought, again, about leaving. I even went so far as to step back to the window, half-lift it, and feel the yard press up against the opening—hot, honest air, the smell of wet soil, a bird yelling about something insignificant. But the itch that had brought me here was not soothed by proximity to escape. It was a hook, and the line led deeper in.

After wandering around a bit more in this strange dollhouse, I made my way to the basement, not sure what I was expecting to find, but I had a morbid curiosity. So I descended the stairs. When I reached the bottom to my surprise I found an elaborate mirror maze. A million me’s reflected in every direction.

The door to the basement was not locked. It was painted the same mild color as the wall, as if it didn’t wish to embarrass anyone by being a door. It swung open with the oiled grace of good manners. The stairs were carpeted in a thread that felt like hotel stairs—functional luxury, nothing that could snag. Halfway down, the air changed. Not colder, not warmer—closer, somehow, as if it had been waiting a long time not to be disturbed.

I flicked the light switch and nothing happened, which relieved me for reasons I can’t fully explain. The light arrived anyway, bleeding up from below, from mirrors catching light from mirrors catching light, a chain of handshakes. At the foot of the stairs I stopped and said “oh” without meaning to.

It wasn’t a maze like at a cornfield. There were no cheesy jumpscares or obvious tricks of glass. This was something a patient person had built with a patient philosophy: the panes were full-height and framed in wood the color of scotch. The floor had a pattern, subtle, a row of black diamonds marching in a reliable cadence, and that saved me; I only realized later that the pattern is how I found my way through. I saw my face infinite times, staggered like a deck of cards, my shoulders at a thousand angles, and in one mirror my hands were closer to my sides than I was actually holding them, and the difference made my heart step. I lifted my arms and watched a hundred me’s lift their arms also, a wind through a field. Somewhere, very faint, I thought I heard a laugh. It was my laugh, reflected all the way down.

As I was walking through the maze I could not shake this overwhelming feeling of being watched, but every time I tried to look to where I felt the eyes, I’d see only an infinitude of myself peering back into me. To this day I still get the chills thinking about that. However after navigating for a while by tracking the floor I managed to make it to the other side of the maze.

What I found was odd, but at this point I wasn’t surprised. It was one of those big doors on a submarine the one with the spiny wheel? I opened it to see what was on the other side. I really wish I hadn’t.

The door was absurd in any domestic context: thick metal, round window, spokes like a sun. It had been installed with care, sunk into the wall with a confidence that suggested this had always been its true location. I touched the wheel and expected cold. The metal was warm, body temperature, the way a railing is after a hundred hands have held it. There were no bolts I could tamper with. The wheel turned in a steady arc and the seals—yes, there were rubber seals—released with a kiss.

Inside there was a massive, an impossibly large ballroom. It looked like it was from the 1950’s. With posh design, velvet and mahogany I think, I’m not really familiar with the minutia of fancy decor, but this was that and then some. In the background a phonograph playing music. It was scratchy and skipping every so often. It was the perfect blend of post war hope and the decaying dread of a dream gone by.

You think you know the dimensions of a house you’ve passed a thousand times. You do not. Space is a polite fiction we all agree on until something refuses to agree. The ballroom would not fit—not in the footprint of that bungalow, not even if you mixed in our house and the Bakers’ and maybe the street. But there it was: a dream’s memory of a hotel, polished floors so lustrous I could see a reversed ghost of myself fourteen feet down, velvet drapes pooling like blood that had learned manners, chandeliers of glass teardrops frozen mid-fall.

The phonograph had its own little table near the wall, the horn like a golden trumpet used to shout at God. The record that spun was thick and real, not a decoration, and it warbled cheerfully when the needle found a scratch and leapt back. I knew the tune in the way you know the mood of a song without knowing its name: it sounded like arriving, like dresses that swish, like the breath before applause.

That isn’t what unsettled me most though. On the floor through the ballroom on the floor there were all of these metal tracks they were all over the place. Upon the tracks moving and zipping around were well dressed mannequins. Moving from here to there, an emulation of dancing and mingling. A frozen mobile mimic of movement. There were easily 50 of them, all of them following the tracks in different ways to different points, like a bastardized recreation of a party by someone who had never met a human.

Mannequins are neutral until they aren’t. Clothes wake them. Whoever had dressed these had known what they were doing: tuxedos, gowns, gloves, pearls that were too lustrous to be fake and therefore had to be, pocket squares in a spectrum of whites like small storms. Their faces were not faces; they were suggestions with noses that had never broken, mouths that understood no verbs. Under their feet, the tracks gleamed with a kind of medical cleanliness, bisecting the dance floor, looping past the long banquet table and around the pillars and into little alcoves where two figures might have a private conversation about nothing.

They moved with the certainty of trains. When two “people” approached one another, a delicate circling occurred, a switch clicked in the floor, a new path took one past the other with the suggestion of conversation. Hands lifted and lowered in pantomime. Heads pivoted with the unctuous gravitas of sculptures acknowledging weather. The illusion worked until it didn’t, and when it didn’t the failure was devout. That’s how I know something was paying attention.

In the middle of the hall there was a large table. I thought to leave but upon turning around I saw from the mirror maze a legion of myself bidding me to stay where I am. I could not resist. When I looked back into the ballroom I had found that for just a brief moment all of the mannequins had stopped, and all of their heads were turned to look at me, regardless of the position of their body. But just for a moment, soon after they began zipping back and forth.

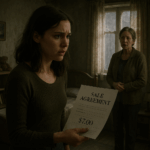

I made my way to the banquet table and saw a card that had a name on it. It was my name. I sat down at the head of the table. There was a platter in front of me. When I lifted it off I was greeted by the ripe aroma of rotten meat and turned dairy. A large buffet of rot waiting to be eaten. I tried to get up, to recoil in disgust. But I couldn’t. I don’t know how I knew but I knew the mannequins would never forgive me if I didn’t partake.

I want to say here, before the next part, that I understand how this sounds. I’ve rolled my eyes at ghost stories that linger too long over the smell of things. But smell is the tyrant sense. The platter breathed death into my face the way a drunk whispers secrets too close to your ear. I saw the gravy skin peeled back like a blister; I saw the veined cheese collapse under its own fatigue; I saw meat with the rainbow sheen of a gasoline puddle. And still—still—my hand lifted the fork because the story required it.

There’s a part of you that is older than disgust, older than rules about kitchens and temperatures and sell-by dates. That part lives under the tongue where language is useless. That part recognized the banquet as an order, the way a dog recognizes its name. I lifted a bite and the forkful trembled like a surrendered confession.

So I did, with one rotten bite, I began. Then another, and another still. Eat bite seemingly restoring the food, undoing the rot. As I kept eating, I noticed more and more that the mannequins were no longer just mannequins. They were coming to life. I continued to eat my delicious meal. By the time I was nearly completion I looked around to the men and women surrounding me, enjoying themselves at my party.

Let me slow it, because time was syrupy there. The first bite went in like a dare and came down as something else. I expected the taste of spoilage, the ruin, the tongue-revolt; what arrived was a memory of the best Thanksgiving I never had, a tenderness that collapsed in an obedient way, a warmth that unfurled down the back of the throat and put a hand on the base of my skull and said, there. The second bite did not taste like the first, because the first had done its work; now the gravy was a river, the potatoes silk, the vegetables bright as a suggestion of spring. With each bite the platter seemed to unspoil itself, like a time-lapse of mold retreating in shame. The air sweetened. The phonograph stopped skipping.

At the edges of the floor, a hand twitched. A head that had been fixed in profile rotated with human impatience, a tiny scold. The tracks underfoot quieted, or maybe I just stopped hearing them. I saw eyes that were not eyes turn toward the table with the greedy focus of people who remember being hungry. A woman in a sparkling blue dress paused at an imaginary quip, then laughed, and the laugh was not wood. It was bell-glass. The chandeliers brightened not by any switch I could see but by consensus.

The waiter arrived then—he had not been on any track I’d noticed—and he was a man with freckles in a constellation across his nose and a smile he had practiced until it warmed without heat. He poured wine into a glass I had not touched and the wine fell the way velvet falls, hush by hush. He said nothing yet; he waited because I had to finish the plate.

By the time I was nearly completion I looked around to the men and women surrounding me, enjoying themselves at my party.

And here is the part that I have not been able to explain to anyone in a way that doesn’t make me sound like I have gone off the road: it became my party exactly at the moment I realized I could not leave. Ownership snapped shut like a cuff. The name card with my name on it looked more correct than my driver’s license. In the mirror beyond the door I saw a hundred me’s seated at a hundred heads of table, hosts who did not remember when they had been guests. The song changed. It was the same song. The room applauded as if someone had to.

Just as my plate ran out of food, a kind waiter approached me and asked politely. “Would you care for some more food? Or perhaps a glass of wine?” I replied that I would like both, and the waiter replied with a smile.

“Indeed, right away Mr. Onyxdragons.”

And I decided to dance.

END!

News

Help. It’s 7:58am Again And It Will Be Until She Smiles

Part 1 I don’t know where else to put this. I’ve called 911. I’ve broken windows. I’ve tried staying awake…

20 years ago, a child went missing. 2 months ago, I found him.

Part 1 I don’t know what I’m doing posting this to a damn internet forum, but I need to get…

I Left With $12—Two Years Later, I Bought Their House In Cash

Part 1 The scent of lilies and stale grief clung to me like a shroud. I stood in front of…

Mom Sold My Childhood Home For $7 And Lied About It

Part 1 The email hit my inbox like a punch to the gut. Not the email itself, but the attachments—screenshots…

My Mom Sent 76 Invites—Guess Who She “Forgot”?

Part 1 of 2 The email wasn’t even addressed to me. It arrived like a digital slap—a sloppy forward from…

Left Out of the $75K Inheritance “Because I Didn’t Marry Well”—Until My Name Was Read Last

Part 1 The cream‑colored envelope felt heavier than paper ought to. It wasn’t just the cardstock—my family preferred thick things,…

End of content

No more pages to load