My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner

Part One

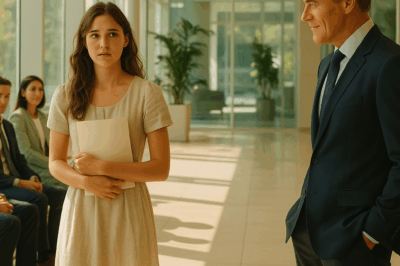

The blood rushed to my fingertips, a bright, useless electricity that made my hands tingle as I held the key card to my own hotel and watched my sister block the entrance like a velvet rope.

Behind the glass, the Grand Azure’s lobby shimmered the way I had always imagined it would when I sketched it on a diner napkin nine years ago—floods of light falling from a canopy of hand-blown crystal, marble veined like storm maps, a sweep of azure velvet curved into little coves where strangers could become stories. Past the revolving doors, a server drifted by balancing champagne like a constellation in motion. The pianist let soft notes pool around the fountain I’d insisted should sing, not splash. Somewhere, beyond the lobby bar and past the gilded screen etched with our compass rose, my father’s laugh cut through everything. Big, booming, rehearsed. I knew that laugh. I’d built a room big enough to hold it and forgive it.

“You can’t seriously think you’re coming in.” Vanessa kept her body between me and the door, taking up as much space as her hunger for an audience would allow. She smoothed the teal satin of her knockoff dress—one I recognized in instant, a copy of a design my friend sent me in confidence from a Paris atelier preview—and widened her eyes in performative pity. “This is the Grand Azure, Ellie. The tasting menu alone costs more than you make in a month.”

If she only knew I’d burnt my fingerprints on that kitchen the year we earned our first star. That I’d written the original menu with Chef Michèle, then stood on the loading dock at 3 a.m. tasting cherries because they told me they were “the best” and I wanted them to prove it. That every chandelier in this lobby had passed through my hands, through my errors, through my insistence.

“He’s my father too,” I said, keeping my voice level even as the envelope in my clutch suddenly felt like lead. Inside it: a deed to a small stone villa wrapped in olive trees on a hill near Cortona. A birthday gift large enough to be generous and small enough to be only mine to give.

“Mother and Dad were very specific.” Vanessa planted her stilettos like stakes. “They only want successful people here. People who won’t embarrass the family.”

The laugh that threatened the back of my throat arrived as a cough. “Yesterday I signed off on a hundred-million-dollar expansion,” I thought, and put the laugh away like a dangerous dress. Today I was a potential embarrassment.

Ten years earlier, when I’d left our parents’ small, tired accounting firm, my father had said it without flinching: “No daughter of mine is going to be a glorified waitress.” He did not ask what the word glorified meant to me. He did not want to hear that numbers without people bored me, that I wanted to build rooms that made tired men soften and women who’d been told “no” so many times they called it a lullaby remember what wanting felt like. So I let them call me waitress and let my work call me builder.

“Ellie.” My mother’s voice came sharp through the air, a little serrated. She was behind Vanessa, pearls huge as teeth, pink lacquer glinting at her finger tips. “What are you doing here? We discussed this.”

They had discussed it. I had received a text message that morning while I was approving a nursery of gardenias for a client suite upstairs. Don’t come to Dad’s birthday. It’s at the Grand Azure. You can’t afford it. Don’t embarrass us.

“I brought a gift,” I said quietly, lifting my clutch an inch.

“Oh?” Vanessa curled her lip. “A gift card to Olive Garden? Or did you scrape together enough tips to buy him something from the mall?”

“Vanessa.” Mother’s tone reprimanded, but her eyes shone with the pleasure of pieces lining up. “Be nice. Your sister made her choices. If she’d stayed with the firm like you did, things would be different.”

Things were different. I knew her firm’s books better than she thought I did. My real estate division had sent me the last three months’ tenant reports. The family firm’s rent came late more often than on time. Their proud new “downtown address” occupied the smallest office on a floor no one wanted—until I bought the building and gilded the staircase and installed a coffee bar no accountant needed but every accountant took a photo of.

“Vanessa’s doing so well,” Mother continued, turning toward my sister the way flowers turn toward the sun that will burn them later. “Junior partner. New house. A fiancé with such good prospects.”

I thought about my penthouse above the Park where the morning is always composed, my quiet collection of cars that could own their own city blocks, the jet I flew in on because red-eyes had taught me the price of my spine. “Yes,” I said. “At least I’m trying.”

“And that dress?” Vanessa’s eyes skimmed me head to heel, varnishing her assessment with pity. “Couldn’t you have made an effort? This is the Grand Azure, not…whatever chain restaurant you manage.”

The dress was simple black silk with a waist cut like a second breath. It had been cut for me in a room where the seamstress had measured my shoulder with her eyes. It had cost more than Vanessa’s car and less than a single sconce on the Crystal Staircase behind her. “It’s what I could manage,” I said, and let the lie sit like a stone with a sweet face.

“You can’t come in,” Vanessa concluded, as if she were sealing a jar. “We reserved the entire VIP floor. It’s for family and distinguished guests only.”

Distinguished. My VIP floor. The one I’d spent months with blueprints and models and marble samples to coax into softness. The one with the private elevator keyed to only one card. The one where the fisherman from wine-country carved me a table from an olive tree that had outlasted three wars.

“Who are the distinguished guests?” I asked, curiosity unspooling.

“Oh, you wouldn’t know them.” Mother flicked her wrist. “The Andersons. The Blackwoods. Mr. Harrison from the bank. All very important people.”

I made a note to be kind, later, when they realized. Thomas Anderson leased three of my buildings. The Blackwoods’ resort application sat in my “pending” folder with a note from Membership: Not yet. Mr. Harrison’s bank had sent a term sheet that needed a kinder interest rate if they wanted me in their corner.

“Right,” I said. “Very important.”

“Exactly.” Vanessa looked pleased. “So you see why you can’t be here. What would people think if they knew Dad’s failure of a daughter was…serving their drinks?”

“Vanessa—” Mother murmured, but her eyes sang.

The laughter I’d swallowed began to bruise. I looked through them at the cobalt burn of the lobby, at the staff I knew by name and story, at the arrangement of things I had argued into being, sometimes with myself. I thought about turning around and taking my laughter with me—the easiest option, always. Then I heard something else, buried beneath my father’s boom and the pianist’s mercy: my mentor’s voice, twelve years ago in a conference room that smelled like copy paper. Black hair, that parted like courage, and a laugh that told truth and made you braver. “There’s no virtue in building a table you never sit at,” Nora had said, when I almost folded the first check someone offered for my first hotel. “If you can’t take your seat, you’ve built someone else’s dream.”

I straightened. The click my jaw made settling back into itself was louder than my heels.

“Actually,” I said, “I think I’ll stay.”

Before the words could land on them, the door I had watched them guard opened. Owen filled the frame like a man who understood thresholds. He and I had turned locks into passageways for seven years. He had seen me sort linens at midnight and argue contracts at dawn. His blues were pressed; his eyes were a line.

“Is everything all right here, Madam CEO?” he asked in a voice designed to be overheard by anyone who needed their world altered. “Your usual table is ready. Chef Michèle is waiting with the tasting flight.”

The silence that followed was spotless. Vanessa’s mouth opened and made a small shape. Mother’s hand found the door handle without looking and clutched it like truth.

“Owen.” I smiled. “Your timing is—” I met his eyes for a second, a thank-you passing like a bird between us. “—immaculate. My family was just explaining that I can’t afford to dine here.”

“Ma’am?” He tilted his head, a dog hearing a note humans can’t. “Pardon. But you own the chain.”

“Yes,” I said, and turned to my mother and my sister with something like mercy under my tongue. “Yes, I do. Shall we go in? I believe you reserved the VIP floor. My VIP floor.”

Gavin appeared then, the cologne that always tried too hard preceding him. “What’s taking so long? Everyone’s waiting for—” He saw me. The false smile he wore like a temporary crown fell, revealing the boy who used to borrow my notes and not return the favor. “Ellie. Didn’t expect to see you here.”

“Clearly.”

“Gavin just made vice president,” Mother said quickly, as if rearranging pieces on a board that had decided to change games. “Junior vice president,” I corrected automatically. Our banking team sent org charts as a matter of course. His bank handled petty cash. We were in the process of buying the bank.

“Actually,” Owen said with professional bafflement, “Ms. Eleanor is the founder and CEO of Azure Hospitality Group.” He didn’t look at my mother when he added, “She owns all thirty-five Grand Azure hotels worldwide, along with the resorts and restaurants.”

Vanessa’s clutch slipped and clapped on the marble with the sound of a small animal dying. “But that’s— that’s billions.”

“Yes,” I said, so gently the word made a cushion for the years before. “So your comment about the tasting menu was— amusing.”

I moved. The lobby opened to let me pass. Staff straightened as if someone had told a story they loved, and it was coming true again. “Good evening, Ms. Eleanor,” Rachel called from the desk. She wore the new silk scarf we’d selected at three in the morning in a budget meeting because numbers are easier to read when you feel beautiful. “The executive suite is ready for Mr. Thompson’s party.”

“Thank you, Rachel.” I glanced over my shoulder at the three people who had raised me and reduced me and rewritten me to fit the margins of their own page. “Coming?”

We took the private elevator. I slid my key into the reader, a thin blade of access. Mother stared at the slim black card like it had slapped her. “Your dress,” she said to the back of my head. “It’s…is that real?”

“Custom.” I pressed the button to the VIP floor. “Paris. The one who wouldn’t take Vanessa.”

The doors opened to the room I had always wanted my father to enter: cobalt and gold, old jazz and new linen, a room a loud man would be quiet in for the sake of a woman who owned it. Conversation stilled. The astonished hush moved like a breeze through candles.

“Eleanor?” my father said. “What are you— Your mother said you couldn’t—”

“Afford it.” I walked to him and kissed the air by his cheek because I am not a child, not anymore. “Happy birthday.”

Mr. Harrison—silver hair like a dignified cloud, permanent nervousness under his watch—rose so fast his chair scraped. “Miss Eleanor! If I’d known— we’ve been trying to reach you. That syndicated loan…” He wore the look of a man who had days of indigestion wrapped in a single sigh, relieved.

“Thomas.” I felt, not for the first time, the bone-deep exhaustion of being asked to fix men like broken glasses. “We’ll meet next week.”

“Miss Eleanor.” Mrs. Blackwood—diamonds like doves arguing on her ears—leaned forward in the way rich women do when they’re about to pretend they were always on your side. “We’ve been simply dying for a slot at Azure Provence. Do see what you can do.”

“I’ll see what Membership says,” I said, and let her hear the capital M.

Father sank as if his chair were a boat and he’d forgotten how to swim. “All this time,” he said, each word a stone, “we thought you were—”

“Your words were ‘glorified waitress,’” I said, the old heat in my throat now cool enough to put my hand in. “You were wrong.”

“Why didn’t you tell us?” Mother demanded, pallor battling rouge. “We’re your family.”

“Would you have believed me?” I asked. I did not whisper. “You didn’t believe me when I wanted to leave a job that suffocated me. You did not ask what I wanted. You asked what the neighbors would think. I learned to stop offering you my truth so you could stop ignoring it.” I let a smile lift one corner of my mouth. “By your metrics, however—” I looked around the room and met the eyes that had always looked past me. “—I am a triumph.”

I lifted the envelope from my clutch and placed it on the table in front of my father. “Vanessa wouldn’t let me give you this outside. It is the deed to a villa in Tuscany. Consider it a birthday gift from your failure of a daughter.” I moderated the sarcasm because I have never liked its aftertaste. “The keys are in your room upstairs.”

The party resumed by force; people have appetites, no matter whose dignity has just been rearranged. Servers in azure jackets hoisted their trays again. The pianist, finding my eyes, shifted into something Lauren Bacall would have leaned against. I fielded congratulations I did not want and requests I accepted because the machine needs oil and I have always understood how to keep it humming. Vanessa’s fiancé excused himself and never returned. (He would call me in three weeks to ask for a coffee. I would decline with kindness because the god I believe in loves mercy more than the story.)

When the cake—dark chocolate, hazelnut, forest berries, our pastry chef’s heart disguised as dessert—arrived with a choir of small fire, I slipped onto the terrace for air. The city spread itself like a promise. Beyond the canopy, the river caught the moon and kept it.

Father found me. He’d loosened his tie, a gesture he thought meant “I am relaxed” and always looked like “I am trying.” He stood beside me and put his hands on the railing, the way men do when they want to lean on something and not show it.

“How many?” he asked, nodding at the skyline as if I were a magician and buildings were my cards.

“Enough,” I said. Numbers are for banks. This I could not explain in digits.

He nodded. “I was wrong,” he said, and it wasn’t easy for him. His tongue had to fight past old pride; the words came out like coins he didn’t want to spend. “So terribly wrong.”

“Yes,” I said, not making the difficulty easier because it had been hard for me, too. “You were.”

“Can you…forgive us?” He looked at the river when he asked it. He always asked hot questions to water; I think it made him feel less likely to burn.

“Forgiveness isn’t the issue,” I said, and watched a boat move like a thought across the black. “Respect is. You never respected my choices. You respect success that looks good at dinner parties.” I turned my head. “Now you can tell people your daughter owns the Grand Azure. You’ll enjoy that.”

He winced in that place where he still hurts, which is to say in his brag. “I’m sorry,” he said again, and it was truer that time.

“So am I,” I said, because we had wasted years like money, because I had kept my joy from him like a treat he hadn’t earned, because he had made me build a world without him and now he had to live there as a guest, and because the girl who left his office with a box of her own things and a back straight as a new idea deserved to hear him beg. “You can start from here.”

The night folded itself around our conversation and put it to bed. I returned to the VIP lounge and did the thing I have learned to do better than any man in any room—be gracious while standing my ground. At the end of the evening I walked my parents to the private elevator, kissed my mother’s cheek because I am a woman and that is how we win soft battles, and put my father in a car with a bow on top because I enjoy a symbol.

Then I went upstairs to my office—my sanctuary of cobalt and walnut and soft lamps—and exhaled for the first time in years without checking whether the exhale would be used as evidence against me. The city glittered like a dress I had once wanted to wear and had since outgrown. The hotel’s night hum—vacuum cleaners murmuring to carpet, ice machines sighing, late-night laughter wove thin—came up through the ventilation like a lullaby I had written and finally set to music. On my desk the acquisition papers lay where I’d left them that morning. My signature looked like a line drawn through my life: before and after.

I poured myself a glass of the good whisky we pour guests when we want to make new stories and carried it to the window. For once, it was not a toast to anything I would have to fight for tomorrow. It was to the seat I had taken at a table I built—and to the woman who had taught herself not to eat standing up.

Part Two

By morning the story had rewritten itself through the lattice of our family like jasmine—sweet, invasive, impossible to ignore. It arrived at my mother’s tennis group on the breath of a woman who had always hated her forehand. It arrived at my father’s firm on the screen of an associate who had always hated his jokes. By noon Aunt Sylvia sent a capital-laden text (ELE! WHY DID YOU NOT TELL US YOU OWN HOTELS! DO THEY HAVE A SENIOR DISCOUNT?). By evening my cousin in Omaha was posting a congratulatory selfie on the VIP staircase as if she had the right to climb it.

The phone on my office credenza burred.

“Miss Eleanor?” Rachel’s voice was careful the way people are when they are bringing noise to a room that has learned to treasure quiet. “Your mother is in the lobby. She insists.”

I took my time descending. You should always descend when meeting a woman who thinks she has always looked up at you.

Mother stood in front of the floral arrangement like a set piece. It was one of my favorites—clouds of peonies with exclamation marks of delphinium, green like a promise. She wore beige like a bandage, pearls like armor.

“Do you have a minute?” she asked, in the tone of someone asking for a loan while pretending they want to talk about the weather.

“Two,” I said. It would be enough.

We stepped into an alcove, the one where we had replaced a painting of a ship with a mirror so women in evening gowns could reassure themselves that everything would stay up where it belonged.

“I was unkind,” she began, surprising us both. “And wrong. I see that now.”

“All at once?” I arched an eyebrow.

She winced. “It’s hard to keep secrets in this town. People have…opinions.”

“About me owning what I built? Or about you not knowing?” I made it sound like a question. It was a diagnosis.

She touched the edge of the table, leaving no fingerprints because she still wore gloves in March like we lived in a different century. “Your sister is devastated,” she said, eyes bright with the potential of a daughter’s tears they could translate into excuses. “You know how she— she’s always been competitive.”

“That’s one word,” I said. “I know how she is.”

“She’s frightened.” The confession landed in her mouth like a foreign object. “She’s always shined, and now…”

“And now,” I finished softly, “her mirror has competition.”

Mother’s mouth compressed. “This is not about mirrors.”

“It always is with you.” I let the softness leave my voice. “You wanted a short conversation. Here it is. There will be boundaries.”

“Boundaries?” She said the word like she’d read it in a book and liked the ending.

“No more pretending I’m poor when it suits your dignity. No more casual cruelty disguised as banter. No more using my rooms to punish me. No more telling people what I do and how I do it. And if you’re going to brag—and you will—learn how to pronounce EBITDA.”

She blinked. “I beg your—?”

“Never mind.” I leaned forward and softened the place where I’d just sliced. “And you will not ask me for professional favors for friends at dinner parties.”

“But the Blackwoods—”

“Membership will handle the Blackwoods,” I said, and the capital M behind the word made a shadow.

She swallowed. “Am I allowed to ask for personal favors?” The word “ask” sounded like something she’d been told once when she was young and had since taught herself not to use.

“You can ask for lunch,” I said. “That is all.”

Her eyes filled. For a second I saw the girl she had been, standing in a thrift store trying on a dress she didn’t believe she was allowed to have. “I am proud of you,” she said, and the sentence had to be dragged past years of malnourished pride. “Even if I don’t understand how to talk about it.”

“We can practice,” I said, because I have learned to do math the hard way. “Just—talk to me like I’m a person. Not a story to make you look good or bad.”

She nodded, dazed with the effort of being decent. “Lunch,” she repeated carefully, as if rehearsing a word she would need later. “Next week?”

“We’ll see,” I said. “I’ll have Rachel send options.” I kissed one full cheek and did not wait to see if relief would find her. It always does, if you give it a map.

By Thursday, Vanessa called. She had never been good at asking. She preferred taking and then suggesting, when caught, that the taking had been a favor to you.

“I need to see you,” she said, brittle bright. “It’s urgent.”

“Everything you want is urgent.”

“That’s unfair.”

“That’s accurate.” I looked at my calendar and saw a window created by the mercy of a postponement. “Four o’ clock. The café on 73rd. If you’re late, I leave.”

She arrived at 4:09 with a shopping bag that used to be expensive before everyone owned one. Her nails were perfect. Her eyes were swollen.

“I’m in trouble,” she announced, placing the bag between us like an offering. “Gavin’s firm— the lease— he said you…”

“I said nothing.” I stirred my espresso. “The numbers said something. Not my job to make math pretty for your fiancé.”

Her face crumpled for half a second before smoothing itself— foundation, practice, will. “He left,” she said, small as a bad thought. “He said if I can’t deliver the lease, he can’t deliver the ring.”

“Good riddance,” I said without sugar. “Let him have his ring and his office elsewhere. You deserve someone who loves you beyond real estate.” I took pity and added, “I’ll make you a list of therapists.”

She stared, offended by the suggestion of help that would actually help. “You won’t— lease to us as a favor?”

“No,” I said, and let the word do what it was supposed to do. “But this is what I will do.” I reached into my bag and took out a folder. “If you want to join the firm the way you have always wanted to, do it on merit. Here is a two-year plan, compiled by Nora—” (of course Nora) “—to help you build a book of business. It is not glamorous. It is not quick. It is adult. If you take it, I will not lift you, but I will stop stepping aside when you run me over.”

Vanessa’s mouth fell open. It looked like childhood and then widened into fear and then closed into something that looked like a woman’s resolve. “Why are you helping me?” she asked softly, suspicious.

“Because you’re my sister and your worst self often borrows my face,” I said, and we both flinched at the accuracy.

Gavin called me three days later. He started with “I think we got off to a bad foot.” I let him finish the dance. At the end, I told him the thing my mentor had told me: there is no such thing as off to a bad foot with a man whose dance begins with taking. We would not be doing business. He hung up without saying goodbye. Bless him.

The following week my father called at 7 a.m., a time of day he had only ever used to ask my mother for coffee from the other room. I let the phone buzz. He called again. I answered.

“Your mother says we owe you an apology over dinner,” he said, each word polished and heavy. “Come by Sunday?”

“Yes,” I said, because I want my life to include mercy where it can. “But I pick the restaurant.”

Silence. “What’s wrong with the Grand Azure?” he asked, mischief showing. Perhaps the laugh I’d always wanted to hear had been hiding behind arrogance.

“Nothing,” I said, and smiled. “I just don’t want you to dine somewhere you can’t afford.” The line crackled, then his laugh—real, rich, softer—rolled down it. “Touché.”

We met at a small place where the napkins were thin and the food was holy. Halfway through the second bottle, he leaned across the table. “I looked in your books,” he said, as if confessing to stealing fruit. “Your auditor sent me the public filings in case I wanted to brag.”

“I’m surprised you didn’t before.”

“I would have if I’d known.” He poured more wine into both glasses, careful not to make a mess he couldn’t clean. “How did you do it?”

I told him pieces. The first broken elevator I learned how to reset because the repair tech was asleep and my VIP guest was awake. The first angel check I turned down because it wanted my firstborn instead. The night I slept in a linen closet because a pipe burst and I didn’t want anyone to know the woman who owned the building was mopping floors in her bare feet. The twenty interviews I failed because men like rooms full of themselves. The way numbers turned into people when you wrote them your name.

“Why didn’t you tell me you were tired?” he asked at the end, not to force an apology but to be in the story.

“Because you were,” I said, and we both drank that truth like water.

When we rose, he hugged me—not the kind of hug a proud man gives a trophy but the kind a father gives a woman who has finally consented to be his friend. “Thank you,” he said, and my throat hurt in the old way, but my shoulders did not. “I will try to be better.”

“You could not be worse,” I said, kind as a cousin, and we laughed because humor is sometimes the only bridge over the decades.

The world did what it does when a woman flips a script. The press sniffed around. A trade publication—one of the little ones that writes to please the large ones—asked for a profile. I said no. Then Nora called and said, “Say yes, but write it yourself.”

So I did. Under “as told to” I told myself the parts I had left out. How owning things didn’t heal the girl who needed permission; how success, when shown to people who love you only conditionally, can taste like ash; how boundaries can be more expensive than real estate; how forgiveness is a luxury, respect a must.

I started to host something I named after Nora without telling her. A Wednesday table at the Grand Azure with eight seats and rules: women only; no pitching unless asked; admit the thing you failed at first; order dessert because we can. The first table filled in an hour. The seventh created a fund. The tenth paid the bail for a chef whose landlord had decided to call the police when she refused to close her pop-up. The twentieth table watched my mother tell a room of women that she had raised daughters who raised her back.

On my father’s next birthday I did not wait for a text telling me what I could afford. I took him, with my mother and Vanessa and Aunt Sylvia, to a small Tuscan hill above the villa with the view of the valley so beautiful it had to be rationed. We ate pane sciocco and pecorino and drank wine from a neighbor who pretended it was awful so we would say it was good. My father stood at the edge of the garden and pointed at the line where the olive groves met the sky. “That,” he said, “belongs to my daughter.” It was the kind of brag I could almost love. Later, when we walked back down the hill, he took my hand. He had not done that since I was decanted into the world.

The day we closed on Gavin’s bank, I took the acquisition packet into the CFO’s office, where a small brass plaque on the credenza read PUT YOUR EGO IN THE LOBBY NEXT TO THE PARASOLS. “Be gentle,” I told him. “Their junior vice presidents will be looking for jobs and wives and cannot handle both at once. Offer them dignity where possible.” We sent Gavin an interview list and a smiley face. I am occasionally small.

In November, the Grand Azure Foundation—an entity I had formed when I hired my first dishwasher because his daughter’s school fees came stapled to his smile—hosted a dinner on the VIP floor. We honored housekeepers with twenty-year pins and the cook who’d shown me that torching the grapefruit made the breakfast room smell like a winter in Florida you wanted to remember. My father was seated between the florist and the night auditor. He laughed correctly, asked questions he waited to hear answers to, and when a server dropped a tray he rose, helped gather the glasses without saying “careful,” and returned to his seat without checking who had seen.

After dessert he stood and tapped his water glass, which I had learned was as dangerous as any weather system. “I want to…say something,” he said, the pause between “to” and “say” long enough to cast silence over men who had been talking for decades. He looked at me and did not look away. “There was a time when I measured my daughter’s worth by how useful she was to me. Then, by how good her successes would make me look. Both were sins.” He swallowed. “Eleanor—” (the first time he’d ever used the name the day he told me it was old-fashioned and I told him it belonged to a queen) “—I am proud of you.” He turned to the room. “And for those of you who think success belongs only to those who make money with numbers at desks—” he gestured toward the bussers —“ask how well you’d sleep without them.”

No one applauded because the room understood it wasn’t a performance. I held his gaze and nodded and felt my feet under me in a way I had not since the day I almost apologized for building a lobby with a fountain that sang.

A week later, Nora flew in and insisted we sit under a plant in the conservatory like women in a spy movie. “You did the most difficult piece,” she said without preamble. “You told the truth and didn’t apologize.”

“You taught me,” I said, and meant it. She poured tea with the precision of a woman who had learned her power the expensive way. “What now?”

“I stop performing humility so people won’t punish me for my confidence,” I said, surprising both of us. “I stop turning my volume down at Thanksgiving. I buy three more buildings and a farm. I call Vanessa every Friday and make her tell me one small failure and one small victory until she learns they can live in the same house.”

“Good,” she said. “And your mother?”

“Lunch once a month. We talk about anything but who she told at tennis.” Nora laughed. “The conditions under which we love are sometimes the love.” She lifted her cup. “To women who don’t own their sisters but build them ladders.”

“To mentors who aren’t threatened by miracles they didn’t make,” I said.

When the holidays came, I hosted my family—not in the VIP lounge but in the small private dining room off the kitchen, where the air always smells like caramel and secrets. I hung paper snowflakes badly and let the pastry team laugh. I put my father at the end of the table closest to the kitchen door because he had learned appreciation and I wanted the staff to feel it pass like a good rumor.

Before we ate, my mother put her hand over mine. “You are…impossible,” she said, meaning magnificent, and I let it be enough. “And I am sorry for all the years we asked you to be smaller.”

“I am sorry for all the years I hid,” I said. “I should have made you come here sooner.” She blinked away water she had promised herself she wouldn’t bring and patted my cheek in the way old women petition gods. “We are here now.”

The staff lined up to sing. I had always thought it a silly tradition, then realized everything is silly if it is not yours. They sang our carol, the one with the chorus we wrote the year the sprinklers went off at midnight and flooded the lobby and we saved it with towels and laughter. Father cried for the first time since I left his office with a banker’s box of colored pens and a heart so full of wanting it almost choked me. He didn’t hide it. Mother wiped his tears with a napkin that cost too much and made no fuss.

After dinner, I took them all upstairs to the terrace and showed them the river again, because some views are too heavy to hold alone. “Remember when I told you not to embarrass us?” my mother said into the cold, because ghosts come out when breath turns to smoke. “Yes,” I said. “I have new policy.”

“What is it?”

“Embarrass them instead,” I said, and she laughed so hard we both leaned on the railing and the staff peeking through the curtains relaxed because laughter is a sign of a safe room.

The next morning, early, before even the bakers had powdered their faces with flour and sugar, I walked the lobby in my slippers as I often do, checking the corners and the corners of corners. A young couple sat near the fountain in their airport clothes, the kind of tired that wraps itself in each other to sleep. I asked Rachel to send coffee and croissants, anonymous, with a note I have become addicted to writing: May your love find rooms that are kind to it.

On the table in my office, Vanessa’s two-year plan lay open with notes I’d made in black ink and courage. On the credenza, a photo of my father on his villa steps in Tuscany, his hand lifted as if to show off land he had neither worked nor paid for but had learned to bless. Under that, tucked into the frame, a piece of paper I had written to myself on the day Nora told me to build my own table: You are allowed to take up space. Sign here.

I signed it again, because sometimes ownership is a daily signature. Then I went downstairs and sat at the corner table in the lobby—the one with the watchful view and the outlet cleverly hidden under the banquette—and ordered the tasting menu I had designed years ago. It arrived like a love letter: the cucumber soup we make when the heat refuses to leave; the scallop, seared only on the side that matters; the lamb that’s been listening to rosemary for four hours. I ate it slowly, wrote notes on the corner of the card, and smiled at the staff who smiled back like a song we all knew the words to.

Guests drifted by and did their ritual double take. Is that…? Yes. The owner eating at her own table. When I stood to leave, a little girl at a nearby table waved, hair in braids, beads clicking like small joy. “I like your hotel,” she whispered when I bent to her ear. “It feels like we are allowed.”

“That,” I said, “is the only thing I ever wanted anyone to feel.”

I slid her a chocolate from my pocket—the good kind we keep above the pastry drawers and hide from men who think hospitality is always for them—and walked to the door I had built and once been blocked at. The bellman held it, eyes kind, posture perfect, the way we teach. “Good day, Ms. Eleanor,” he said. “Will you be back for dinner?”

“I live here,” I said, and stepped into a city that finally knew it.

END!

News

A POOR GIRL arrived WITHOUT SHOES at the INTERVIEW – MILLIONAIRE CEO CHOSE her among 25 CANDIDATES. ch2

A POOR GIRL Arrived WITHOUT SHOES at the INTERVIEW – MILLIONAIRE CEO CHOSE Her Among 25 CANDIDATES Part One…

POOR SECRETARY RENTS A BOYFRIEND FOR $500—HE’S A MILLIONAIRE CEO WHO CHANGES HER LIFE… ch2

POOR SECRETARY RENTS A BOYFRIEND FOR $500—HE’S A MILLIONAIRE CEO WHO CHANGES HER LIFE… Part One Elena Rivera typed…

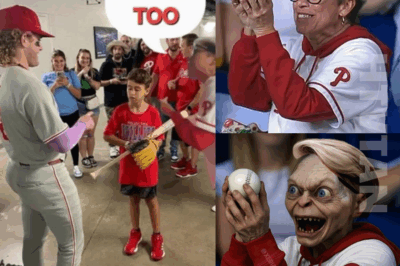

Phillies “Karen” Faces BRUTAL Fallout After Viral Ball Snatch

From stadium BOOS to online SHAME and RUMORS of job loss, the woman branded a “Karen Hall of Fame” member…

My Parents Said, My Sister’s Wedding Day, It’s Better I Not Be There So, I Vanished… ch2

My Parents Said, “My Sister’s Wedding Day, It’s Better I Not Be There.” So, I Vanished… Part One The…

“You’ll Get the Ball Back, But Not Where You’d Like It to Be” — Whoopi Goldberg Slams ‘Phillies Karen’ After Viral Ballpark Drama

A Phillies fan branded “Phillies Karen” sparked national outrage after being caught on camera taking a home run ball from…

Phillies ‘Karen’ is facing the WORST backlash ever fans are NOT holding back…Should this be stopped?

Phillies “Karen” Faces Brutal Fallout: Viral Shame, Job Rumors, and a Stadium Exit From Outrage to Redemption: The Aftermath…

End of content

No more pages to load