My Mother Mocked Me As Poor And Put Me In Room 108, But At Dinner I Exposed Their Lies And Reveal

Part One

My mother looked me dead in the eyes, smirked, and said, “You belong in Room 108 with the servants. That’s all you’ll ever be.” The words landed with the particular cruelty she favored — precise, rehearsed, and aimed to define me. She had never missed an opportunity to tuck me into a little box of humiliation. For her, labels were currency: what you were called made you what you would become. That night something inside me shifted. I had been careful for a long time, and I had learned the language of endurance, but I was not made to be erased.

My name is Calder Ree. I’m twenty-three, quiet by temperament, and for most of my life my family mistook quiet for weakness. Dalia, my mother, never saw me as her son. She saw me as an embarrassment she had to manage — a lingering note of her failed marriage. In the Rees’ world, appearances were everything: the right label on a coat, the right school name, the right accent at the club. If you didn’t match the script, you were marginalized.

When the extended family was called to Grandfather Augustus’s estate that spring, the whole house felt like a stage. Chandeliers glittered, and the mahogany corridors smelled faintly of polish and old money. They handed out keys like little announcements of rank. My cousins received envelopes with room numbers that were small triumphs — suites on the east wing, large windows, private baths. For me, the envelope bore the tarnished brass of Room 108, a narrow door near the kitchen that smelled faintly of bleach. The carpet was worn, the wallpaper faded, and the bed creaked when I sat.

It was deliberate. My mother wanted me tucked away, a secret nobody had to explain. She wanted me out of sight so that her polished narrative wouldn’t be marred by the sight of her son toiling at some humble job while she smiled at galas. I sat on the edge of the thin mattress and listened to the low rumble of the house — footsteps on polished floors, laughter like glass clinking — and I felt the cold fact of my exclusion.

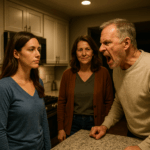

At dinner, she made sure everyone heard her voice. She leaned back like a queen presenting a tableau and said, “It’s no wonder Calder can’t keep up. He doesn’t understand what it means to have real money.” The cousins chuckled in the practiced way of people who know the social hierarchy and have vested interests in preserving it. Sterling snorted. Ranata put a dainty hand to her mouth, betrayal disguised as amusement. Lawson’s gaze slid over me with that smug expression he always wore, like the world was his and I was an intruder.

I sat across from them with a plain shirt under borrowed jacket sleeves and watched their polished lives glitter under the chandelier. They lived their lives like advertisements for privilege: tailored jackets, shoes that reflected every light, stories about internships that were really family favors. They loved to remind me how little they perceived me to be. Sterling leaned forward, the smirk obvious. “Do they even pay you at that job?” he asked, loud enough. “Or do you just get meals and call it even?”

The laughter felt like an attempt to carve me down to size. Ranata, who cultivated a porcelain-pastel sweetness, added pitying concern that stung worse than the mockery. “Don’t tease him too much,” she murmured. “He doesn’t understand.” They imagined my silence as collapse, my quiet as proof of my place.

Silence had been my armor for a long time. Words only gave them more ammunition, so I kept my mouth shut and watched. There is a particular kind of observation that isn’t idle; it’s a patient study of movement, tone, and the small tells people leave behind when they pretend. If you watch enough, you begin to see the seams. Sterling’s laugh faltered when Grandfather’s business was brought up; Ranata’s manner stiffened when asked about her job; Lawson avoided any specifics about classes or ambitions. Their stories, polished as they were, had splinters under the varnish.

Augustus Ree was the kind of man people lowered their voices for when he entered a room. Time had bent his back and smoothed his edges, but the authority was still there. His empire — shipping, property, hospitality — stretched across states and industries, and every scrap of it had been built by this quiet man’s discipline. When he spoke, the room settled. His grandchildren crowded to him with their little triumphs, hoping for an approving nod. He listened to them, but he listened differently. His eyes occasionally found me across the table, and the look in them was never ridicule.

In corners and in whispers, my name was used as a warning. “Imagine putting the company in his hands,” my Uncle Marcellus said once, leaning close. “It would collapse in a year.” Dalia nodded, a practiced look of worry on her face. “He doesn’t understand responsibility. He’s too quiet. He’s not built for it.” They painted me as fragile, as unfit, and hoped that by telling the story often enough Augustus would accept it as truth.

I learned to carry the quiet weight of their opinions like a cloak, but I never stopped listening. I studied them not to become them, but to learn the architecture of their armor. Their vanity was a construction; mine became a study in counterweight.

Later that night, back in Room 108, I opened a small drawer in the faded desk more by habit than hope. It stuck at first — wood swollen with age — then gave. A thin envelope was tucked behind dust. My name was written on the flap in Augustus’s hand. I recognized it instantly. For a moment I thought it was a mistake. People do not always leave their heir-apparent letters in service quarters. Slowly, reverently, I slid the paper free.

Augustus had written to me. Not to my mother, not to the cousins, not to the family lawyer. To me.

Calder, the letter began, his hand steady even on the furnished page. You may not understand now, but I have always seen in you what the others do not. Where they show greed, you show patience. Where they demand, you listen. That is why, when the time comes, everything I have built will be placed in your care.

My heartbeat accelerated. He went on, and the lines beneath his careful script cracked the floor out from under me.

Your mother, Dalia, betrayed me once. She siphoned funds from a shipping contract to seed her own ventures—secret transfers that nearly cost us a major contract and put years of work at risk. I forgave her publicly to protect the family’s name, but I did not forget. Do not trust her. She will do anything to take what is not hers.

The second paragraph was a fossil of a scandal they had kept hushed. The very person who had shoved me into a servants’ room and called me nothing had committed a crime to feed her private vanity. My hands shook. The letter continued with instructions, wisdom, a charge to be patient and above retributive passion. Augustus’s handwriting closed with a simple line: Stand firm. The truth is your shield.

There is a strange alchemy in holding a truth that can topple a narrative. For years they had tried to define me by their assumptions; now I had a document in my hand that dismantled their core. The letter did not merely name me as the rightful steward of his legacy — it named the rot they’d cultivated. In that cramped room, with the wallpaper peeling, I felt a change: a strategy forming around the knowledge that they had been false.

When the formal dinner came again, the table was a polished stage for performances. Dalia’s smile was sharper than ever, a practiced curl. She leaned forward to lead the chorus of condemnation. “You should be grateful for your place, Calder,” she murmured loudly as if her care were a miracle. “We keep what’s left of you.” The cousins snickered, waiting for me to shrink as expected.

But I did not shrink. I let their words echo in the chandelier-lit room like a sound I could repeatedly view from the inside. I had become an archivist of their behavior. Patient observation had been my real job. The truth I carried was not a weapon to be brandished in anger but a key I would insert at the right hinge.

As dessert plates were cleared and the murmurs settled into a hush, Augustus set down his fork. The moment he cleared his throat, the room held its breath. His voice was soft but carried the weight of years. “It is time,” he said, “to decide who will carry on this family’s legacy.”

Dalia straightened in her chair like a woman who’d sat in the head seat her entire life. Her voice flowed with the rehearsed cadence of someone who had practiced gratitude and loyalty for cameras: “Grandfather, I have dedicated myself to this family. I have protected your interests. I have made sacrifices. I believe I have earned your trust.”

Sterling and the others nodded, their smiles bright. They expected the usual: a toast, a general blessing, perhaps a small assignation of responsibility. They had not prepared for truth.

I stood. The note in my pocket felt like a small stone. I unfolded it and read aloud, calibrating my voice to the cadence of the room: “Augustus has written that he has seen more in me than the others — that where greed resides in them, patience resides in me. He wrote that my mother siphoned funds from a shipping contract to fund her ventures, nearly costing the firm. I have proof in his handwriting that he did not forget.”

The reaction was immediate. Forks clattered on plates. Dalia’s face drained from triumphant rouge to stunned, then furious. Sterling’s jaw tightened and his eyes darted like a hunted animal’s. Ranata’s hand trembled as she clutched a napkin. Lawson’s smugness fell away to blankness. Augustus watched me with a small, assessing calm. When I finished, all the rehearsed performances at the table crashed like stage props in a sudden wind.

“Your handwriting confirms this?” a cousin whispered, dread sharp in her voice. Augustus nodded. His voice, when it came, was brittle with years of disappointed patience. “Calder has been patient. He has listened. He is the one who understands stewardship.”

My mother tried to speak — fast, sharp, half truth and half accusation — but the room had shifted. Her claims had always had the perfume of performance. Now they smelled of something fainter: the fear of being revealed. Dalia’s face twisted in rage. “You cannot be serious,” she spat. “He’s nothing, that boy! He’s never shown… He’s… ” Her words frayed under the weight of the paper in my hand.

Augustus’s decision was not a fist slammed; it was the precise closing of a door. “Dalia,” he said, “your position here is compromised. You have had access to company funds and you abused that access. You will have no claim to control.” The statement landed with the double force of moral and corporate consequence. The cousins turned on Dalia with that terrible speed which only family can generate — loyalty shredding into accusation. She had convinced them of fictions for years; now the fiction had burnt to ash.

Dalia stormed from the table with a threat that did not carry menace so much as the exhaustion of someone who had misread her own script. She had a moment of furious clarity — “This is not over!” — and then she left, her footsteps hollow on the polished floor. Her empire of posture had cracked.

The rest of the night was quiet, the sort of subdued stillness that comes after a storm passes. I sat in the head seat, the weight of Augustus’s trust heavy but not crushing. Responsibility is heavier than revenge. I was not interested in theatrics; I was interested in stewardship.

Part Two

The weeks that followed were a weather system of small but unrelenting administrative changes. Augustus, with measured certainty, began to include me in meetings and introduced me to the managers who oversaw shipping lines, hotels, rental properties. He taught me that legacies are not simply handed down; they are tended, like an orchard — with plans for crop rotation, soil health, and, unexpectedly, kindness for the workers.

I read contracts by the light of early mornings. I learned the cadence of numbers. I learned to ask questions that were not rhetorical. I walked warehouses and met the dockworkers who loaded and unloaded the ships, and I listened to their complaints. I visited hotels and sat in lobbies not to be seen, but to hear what guests praised and what they did not say. I discovered that much of the firm’s good standing rested on quiet people who knew how to make others’ days run smoothly.

In boardrooms, people measured me with suspicion and curiosity. “The boy from Room 108,” one manager muttered. I wore the phrase like iron: it had once been mockery, but now it was part of the map to how I’d been shaped. I never allowed that to be the definition of who I was. Room 108 had been a nursery of endurance. It had taught me what Augustus wrote about: patience, listening, and the importance of context before judgment.

Dalia retaliated. She hired lawyers who were forest of legalese and motions, trying to claw back control through litigation and slander. She met with investors and whispered about my youth and supposed incompetence. The cousins attempted to sabotage contracts and salvage crumbs of influence. Sterling tried to organize a coup of sorts by building alliances. Ranata sent a string of careful letters to clients apologizing for “”temporary confusion”” and attaching brochures of her “new management style.” Lawson avoided the cameras and the responsibility as though both might stain him.

But the truth has a gravitational pull. Augustus had left in writing the reasons for his choice. Legal documents, witnesses, and his own reputation made Dalia’s claims look like desperate flailing. Her supporters dried like summer mud when held under a microscope. Even some of Dalia’s old friends who loved the cheap drama of rumor grew wary when confronted with the gravity of corporate governance and auditors’ reports.

The first big test came when an old shipping partner — a firm that had been with us through storms and downturns — demanded reassurances. They interviewed me and the leadership team. I did not posture. I did not play to an audience. I spoke plainly about risk mitigation, transparency, and the importance of ethical bookkeeping. We addressed the past and presented a plan for clearer oversight. The partner’s hand shook as they extended the contract back to us; good governance had been the medicine they needed.

Internally I made two promises: I would never let humility be mistaken for weakness, and I would not lead through fear. Where Dalia had used power to elide responsibility — spend in secret, slough off consequences — I wanted to build systems to prevent that from happening again. I implemented transparent audit policies, opened regular channels for frontline employees to speak directly to managers, and reworked the incentive structures to reward long-term reliability over short-term flamboyance.

The changes were not painless. People who had prospered under a system of favors grumbled. There were awkward board meetings and veiled conversations at estate parties. But the company’s financial health improved not because of a flashy plan but because of slow, steady attention to basics. Cash flow stabilized. Contracts were renewed. Workers — the people I had met in docks and kitchens — noticed that their grievances were being addressed. Their tone in passing us in corridors shifted from weary suspicion to cautious hope.

My position in the family, however, did not morph overnight into reconciliation. Reparation is not a one-time event; it is a long series of choices. Dalia took a long time to come to any conversations that did not involve lawyers. When she did come to the estate months later, she was smaller, wearing the gaunt look of someone who had spent more time touring courtrooms than living. She wanted a meeting. I agreed, and we spoke in a small study where the rain pattered soft on the panes.

“This was never about you, Calder,” she tried to say, the old theatrical cadence still trying to magnify her.

“It was always about you,” I replied. “About the way you defined yourself through what you took rather than what you gave.”

She flinched, not because my words pricked but because the clarity in them reflected a truth she had never allowed herself to accept. There were moments of raw confession from her lips — admissions of fear that had been translated into greed; the terror of being forgotten had turned her toward theft as a kind of insurance. She told me that when my father died, she’d felt the roof of the world crack. “I did what I thought would keep us afloat,” she said, not as apology. She was watering the confession with the hunger for absolution.

I listened. There is a radical, unpopular act in leadership that often separates the strong from the tyrants: the ability to hear without immediate condemnation, to assess, to decide whether the wound can be treated and whether the trust can be rebuilt. I set terms. She could be present in family gatherings if she sought therapy and contributed transparently to the company’s restitution plan. There would be no immediate access to funds, no private accounts to be used as shadow slush funds. Those were not punitive measures; they were necessary safety rails.

In time, Dalia kept the appointments and began to do the slow, humble work of reconciliation. She volunteered at community programs the company sponsored and slowly learned to find value not in the glare of social notice but in punctual labor and honest tasks. She was far from whole; there were relapses into pride, small grasses of old habit, but the big weeds of secret embezzlement had been removed from the garden.

The cousins had to reconfigure themselves. Some left, their appetites for grandeur clashing with a new regimen of accountability. Sterling moved abroad to manage a smaller portfolio; Ranata took a fellowship in public relations that, to everyone’s surprise, humbled her into competence rather than photo ops; Lawson enrolled in a certificate program and started to show up. The family’s social life shifted from a glittering series of displays to a more practical, quieter set of obligations. Not everyone was happy. Not everyone survived their own adjustments. But the company regrown in slow honesty became healthier.

I learned to lead by listening. I took pains never to conflate soft voice with softness of spirit. Leaders can cultivate temperate strength without cruel theater. I befriended managers, walked factory floors at dawn, answered phones when an operations slip-up required immediate triage. The staff began to trust that their concerns were heard and that the people at the top were not an abstraction. I set up town-hall meetings and portals for workers to suggest improvements anonymously. We built an apprenticeship program for the youth in the shipping towns. It felt like building a ladder rather than an altar.

Family dinners, the old warfronts of my humiliation, became less dramatic. They were quieter and, surprisingly, more honest. We still bickered — small, human quarrels about estate etiquette and vacations — but the theater had gone. On the rare occasions that old wounds flared, we had tools to manage them: direct conversation, mediated meetings, and some boundaries that were nonnegotiable. The room that had once been mine in the servants’ wing remained a historical oddity — a story we told the children like a parable. Room 108 had not been erased; it had been reframed.

If you ask me what revenge is, I will answer simply: it was not to crush them. It was to build a life that could not be stolen by rumor or scorn. It was to make the world require their respect rather than demand their performative theatrics. The true triumph was the life beyond the dinner table: workers whose children had a program to apply for, hotels that had happier staff, shipping lines that ran without drama because the incentives were aligned. The empire was resurrected as a tool that could serve more hands than just ours.

Years later, at a small garden party where the grandchildren ran barefoot between boxwood hedges, Dalia approached me quietly. She was older, softer, lined with a humility that had cost her many things. “I was wrong,” she said. Her eyes were not glib. She had done the work of looking at herself, and she had come to a truth that does not often reveal itself: that shame mismanaged is destructive; that greed gathered like rot can be pruned.

“You hurt me,” I said, not because it was dramatic but because the truth needed naming. “You pushed me into a corner and left me to find my way out.” There was no theatrical forgiveness. There was an exchange of honest currency: admission, accountability, and deeds. “I know,” she answered. “And I am trying to be different.” It was quiet, imperfect: necessary, human.

In the end the letters Augustus left — the ink on the paper waiting in Room 108 — were less about legalities and more about seeing. He had seen what mattered in me when others had not. He had trusted patience and moral steadiness. He had built a compass I could follow. My stewardship became the quiet work of tending not a crown but a responsibility.

My life’s work did not become a pulpit of victory. I did not rub their noses in the dirt of their old arrogance. I restructured, reformed, and reallocated. I made the company leaner where it needed to be and richer where it mattered: in the dignity of those who worked there and in the trust of partners who counted on stability more than spectacle.

Once, when a distant cousin — a child of Ranata’s — asked me what Room 108 had taught me, I smiled quietly and said, “That being pushed into a small place gives you the skill to notice wide things.” It was an oddly true thing. In that cramped room I learned how to listen, how to hold truth like a tool, how to measure people by their actions not their boasts. I learned that power without responsibility is brittle. I learned how to be patient until the right door fell into my hands.

There is clarity in a good ending that is not about erasure but about repair. My mother’s mockery stung; her schemes nearly destroyed the work of generations. But the ending was not her ruin alone. It was a recalibration: a family forced to see what they had become and a company reinvented to be just enough of an engine for good. It was a life that continued in rooms that were warm and houses that were open on purpose.

The last time I slept in Room 108 was years after the dinner, one late October when I returned to the estate not as a marginalized boy but as a man who had learned the trade of governance. I opened the door and ran my hand over the faded wallpaper. I thought of the envelope in the desk years ago and how it had changed everything. Room 108 had been a trial not a prison. It had been where I learned the value of truth tucked in humble places.

As I left the house that morning, the sun sliding across the driveway, Augustus at my side walking slower now but with a satisfied glance, I felt a balance settle in the air. The empire was no longer a flame to be fought over; it was a shared responsibility. My mother and I had not had the storybook reconciliation; some wounds stayed with us like faint lines. But the lie that had once defined a family was named and corrected.

And so the truth remained: humiliations could be endured, falsehoods could be exposed, and a life, built patiently, could outgrow the room to which others — in a moment of bitterness — had tried to confine it. Room 108 was no longer where I belonged because of shame; it was part of my history and, in a way, part of my education. I had been mocked as poor, tucked away, and told to be less. At the dinner table I exposed their lies, and in the slow aftermath I revealed who I truly was: a steward of something larger, a man who turned shame into quiet strength and who learned to lead with patience and truth.

Part Three

Augustus died three years after that spring dinner.

He slipped away the way he had lived: without theatrics, early one morning, the nurse finding him in his armchair by the window, a book face down on his chest and sunlight on his hands. The doctor said it was his heart. I thought it was simply time catching up.

Grief is strange when it comes laced with gratitude. I mourned him as my grandfather, the only adult in my childhood who had ever bothered to look past my mother’s narratives. I also grieved as his successor, suddenly aware that the training wheels were off. His handwriting in that letter had warned me the day would come. The day was here.

The funeral was a grand, necessary thing. Old shipping partners flew in on private planes, clergy in polished collars said lines about legacy and dust, and the cousins wore black like a costume change. The church smelled of lilies and sea salt brought in on people’s coats.

After the service, the family gathered at the estate for the formal reading of the will, though none of us were truly in suspense. The letter I’d found in Room 108 had not been theater. It had been a mirror.

Still, the law likes ceremony.

We sat in the oak-paneled library: relatives on sofas, their spouses on gilt chairs dragged from the formal dining room, the family lawyer at the desk that had been Augustus’s. Afternoon light slanted across shelves of leather-bound books. I remembered sitting in this room as a boy, hiding behind a chair with a comic book while the adults discussed “things you don’t understand yet.” Now I was one of the adults. The irony wasn’t lost on me.

Mr. Haines adjusted his glasses and began.

There were bequests: to staff members, to charities, to each grandchild a small, specific gift — a watch here, an old model ship there, a painting that had hung in the hall outside the nursery. Augustus had always liked to match people to objects as if curating a series of private museums.

When he got to the company, the lawyer’s voice took on a more formal cadence.

“I, Augustus Caius Ree, hereby leave controlling interest in Ree Holdings, including but not limited to Ree Shipping, Ree Hospitality, Ree Properties, and any associated entities, to my grandson, Calder Isaac Ree, to hold in trust during his lifetime for the benefit of the family and employees.”

The words fell like gentle stones in water, unavoidable ripples spreading across the room.

No one gasped. We’d all known this was coming.

But knowing something and hearing it read aloud, in a room ringed with faces that had once watched you carry trays, are different things.

My mother’s jaw tightened, but she said nothing. She had already lost this battle in a deeper court.

Sterling shifted, but he didn’t slam a fist or storm out. Even he had learned, in the intervening years, that some fights are simply losses you have to tuck into your jacket and carry home in silence.

Afterwards, people lined up to shake my hand, some with genuine warmth, some with the kind of brittle cheer that says, “I would be nicer if this benefitted me directly.”

“You’ll do fine,” Uncle Marcellus said, clapping me on the shoulder. “Just don’t overthink the shipping routes. The ocean doesn’t care about your spreadsheets.”

I smiled. “I think it cares about both,” I murmured.

At dusk, when everyone had gone, I went to Room 108.

It felt important.

The corridor was the same: faint smell of bleach and old paint, the hum of the industrial fridge from the kitchen below, the echo of distant dishes. I opened the door and sat on the bed. The mattress was still thin. Someone had replaced the worn duvet with a fresh one at some point, but the bones of the room remained.

I took Augustus’s letter out of my pocket—by then I’d had it copied and stored in a fireproof safe, but the original always stayed close—and read it again.

Stand firm.

“All right,” I said aloud to the empty room. “I will.”

The years that followed were heavier.

It’s one thing to be an heir-apparent under the eye of a patriarch; it’s another to be the person everyone points to when something goes wrong.

The world changed faster than even Augustus had predicted. Shipping regulations tightened, then loosened, then shifted laterally into environmental scrutiny. A scandal at a rival firm put every maritime company under the microscope. Our hotels had to adapt to a new generation of travelers—people who valued sustainability bullet points as much as thread counts.

And then there was the journalist.

Her name was Lena Hart, and she wrote like a surgeon: precise, controlled, occasionally cutting. She published a piece in a regional paper about “Old Money, New Scrutiny,” using our family as a case study of generational wealth and accountability. It was fair, mostly. She mentioned my mother’s embezzlement, my grandfather’s quiet handling of it, and my subsequent reforms.

What she didn’t know was that Dalia had been the tip of an iceberg.

Margaret, our new internal auditor, found the rest.

“Your grandfather was meticulous,” she told me in a meeting one Tuesday. “He kept the company honest. But wherever he made exceptions for family, rot started.”

She laid out a file thick enough to be its own doorstop.

Side deals Sterling had made with port authorities.

A shady biodiversity “offset” Ranata had signed off on without understanding, essentially greenwashing a dirty jet fuel contract.

Lawson, surprisingly, was clean. He had barely had enough initiative to sign timecards, let alone orchestrate fraud.

“We can bury this,” Margaret said. “Quietly fix what we can, hope no one notices.”

“What’s the alternative?” I asked, though I already knew.

“We self-report what we need to,” she said. “We clean it from the inside and invite regulators in on our terms instead of theirs.”

It was a stark choice.

My mother’s generation would have picked secrecy without even calling it that. It would have been “prudence,” “protecting the name.”

But secrecy had almost broken us once.

“I’ll take the second option,” I said. “We clean. And if the house shakes, it shakes.”

It shook.

Fines were paid. Statements were issued. Sterling was quietly removed from anything that involved money and given a ceremonial position that required showing up at charity functions and not talking to the press. Ranata had to do a public education campaign about genuine environmental offsets, which, to her credit, she threw herself into, perhaps out of penance.

Lena Hart wrote a follow-up article, one I clipped and kept in a drawer: “When Old Families Choose Transparency.”

In it, she quoted dockworkers who said things like, “We never thought we’d see the day they’d admit anything,” and a hotel housekeeper who shrugged and said, “As long as they keep paying us on time and fixing the leaky windows, they can confess whatever they want.”

It was not glowing praise.

It was real, which was better.

During those years, my personal life started to look… less like Room 108 and more like something I might have chosen.

I met someone.

Her name was Eliza. She was a structural engineer we’d brought in as a consultant when we decided to retrofit our older warehouses to withstand rising storm surges. She had sharp eyes, a dry sense of humor, and the kind of hands that looked natural holding blueprints or a coffee cup.

We argued in our first meeting about the cost-benefit analysis of raising a dock.

“If you don’t, you’ll be paying out more in damages in ten years than you save now,” she said.

“If we do, my CFO will have a heart attack,” I replied.

“Then tell him to eat more vegetables and get used to reality,” she said.

I laughed, startled. I wasn’t used to people in meetings talking to me like that.

We raised the dock.

We built others.

We began, in small ways, to admit that the sea we’d shipped on for generations was not the same sea our great-grandfathers had known.

Eliza and I started getting coffee after site visits. It was slow, awkward, the way adult relationships often are when both people are busy and wary.

“You grew up in this?” she asked once, gesturing vaguely at the estate, the name, the company.

“I grew up in its shadow,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

When I finally invited her to the estate for a family dinner, I braced myself.

Dalia was there.

She was cordial, even kind. The years of therapy had made her less sharp, though the old instincts peeked through sometimes like weeds around a sidewalk.

“So, Eliza,” she said, “what do your parents do?”

Eliza smiled. “My mom is a nurse. My dad is a plumber,” she said.

Dalia blinked, then nodded slowly. “Honest work,” she said, and for once there was no sneer.

Progress.

Part Four

The first time I brought my own children to the estate, it felt like closing a circle.

My daughter, Lia, was four and already telling people she was going to be a “boat fixer” like Mommy, which made Eliza glow. My son, August—named with permission, not as a claim—was two and more interested in the gravel in the driveway than in any of the portraits on the walls.

I watched them race down the hall where my mother once grabbed my shoulder and steered me toward the servants’ wing.

“Careful!” I called. “No running by the stairs.”

They ignored me, as children are duty-bound to do.

“Your grandfather would have loved them,” Dalia said from the doorway, softer now, hair gone silver.

“Which one?” I asked.

She smiled faintly. “Both,” she said. “Yours and mine.”

We had reached a place that wasn’t quite friendship and wasn’t quite the wary truce of earlier years. It was something slower and sturdier: two people who had been utterly wrong about each other in different ways and had lived long enough to see some of it.

“Can we see your old room?” Lia asked that evening, her mouth full of potatoes at dinner.

“Which one?” I asked again.

“The one you lived in when Nana was mean,” she said. Kids absorb family legends like sponges and wring them out at inopportune moments.

The cousins choked on laughter.

Dalia winced.

“It’s fine,” I said. “Yes, we can.”

After dinner, I led them down to Room 108. The door was still marked with the same brass numbers, polished now. We’d done basic renovations on that wing a few years back for staff comfort—new mattresses, fresh paint—but I’d insisted on leaving 108 mostly as it was, within reason.

“It’s small,” Lia said when I opened the door.

“It felt smaller when I was your age,” I said. “But it’s also where Grandfather left me a letter that changed everything.”

“About the company?” she asked.

“About who I could be,” I said.

She considered that. “Why did Nana say you were poor?”

“Because she was afraid,” I said gently. “And when people are afraid of losing something, they sometimes push other people down to feel taller.”

“That’s silly,” August declared, whether about fear or pushing I wasn’t sure.

“It is,” I said. “But it happens.”

Lia ran her fingers along the windowsill. “Do the people who work here still live in rooms like this?”

“Some do,” I said. “Some have houses in town. We try to give them choices.”

“Good,” she said. “Everyone should have choices.”

Out of the mouths of children.

Later that night, after the kids were asleep in the east wing suite that had once belonged to Sterling, I sat on the porch with Dalia. The air smelled like night-blooming flowers and salt.

“I thought putting you in that room would make you leave,” she said quietly. “Or at least know your place.”

“I know my place now,” I said. “It’s just not the one you chose.”

She exhaled, a slow, tired sound.

“I felt like a foreigner in this house my whole life,” she admitted. “Your grandfather… he was kind in his way, but he was also relentless. Your father died, and suddenly it was just me and a child and a name I didn’t know how to carry. I thought if I controlled everything, I’d be safe.”

“Safe from what?”

“Being nothing again,” she said. “Being Dalia from the wrong side of town who married up and then got thrown back when they were done with her.”

“You were never nothing,” I said. “You just couldn’t see yourself without a stage.”

She smiled bitterly. “And you?”

“I thought I was nothing for a long time,” I said. “Then I realized being underestimated is a kind of freedom, if you use it right.”

“Do you forgive me?” she asked.

It was the question people often go hunting for in old age, as if absolution were an inheritance.

I thought about it. Really thought.

“I don’t wake up angry anymore,” I said. “I don’t rehearse what I would say to you if I could go back. I don’t define myself by what you did. If forgiveness is letting go of the fantasy of a better past, then… yes. I forgive you. As much as I can.”

She nodded, eyes shining. “That’s more than I deserve,” she said.

“Maybe,” I said. “But it’s what I needed.”

She died the following spring.

We buried her on a hill overlooking the sea and the warehouse roofs, not far from Augustus. The service was smaller than his, quieter. No reporters. Just family, staff, a few old friends who remembered the version of her that had sparkled before fear turned inward.

At the reception, Ranata said, “She really did love you, you know. Just… badly.”

“I know,” I said.

And I did.

Love badly done can burn. It can also, in hindsight, be recognized as effort filtered through damage.

Years rolled on.

Ree Holdings became less of a family fiefdom and more of an institution with a conscience. We instituted profit-sharing, expanded the apprenticeship program, partnered with environmental groups to make our shipping cleaner. We still made money—lots of it—but we stopped pretending the only metric that mattered was the line on a graph.

Lena Hart wrote one last piece, this time not about us specifically but about a trend: “When Legacy Families Stop Pretending They’re Gods.” She emailed me a copy with a note:

For the record, if more of your peers did what you did, I’d be out of a job. In the best way.

I printed it and pinned it on a board in the HR office, where the safety guidelines and holiday party sign-up sheets lived.

I never moved into the estate permanently.

I kept my small house in town—a renovated brick place near the harbor with a crooked porch and a kitchen I actually used. Eliza and I raised the kids there, walked to the Saturday market, and treated the estate as a place of work and history, not a throne.

Sometimes, late at night, when the harbor was quiet and the only sound was the distant clank of rigging against masts, I’d think about that first night in Room 108.

The humiliation.

The thin mattress.

The envelope in the desk.

If my mother hadn’t tried to tuck me away, I might never have found that letter.

If she hadn’t mocked me, I might have kept trying to win her approval instead of stepping outside her lines.

It didn’t make what she’d done right.

But it did, in the odd accounting of life, mean that even her worst act had been folded into the story of my becoming.

People sometimes ask me, at conferences or in interviews or when I visit universities to lecture about corporate ethics, what my “defining moment” was.

They expect me to say “the will reading” or “the first time I signed a major contract.”

I always surprise them.

“My defining moment,” I say, “was when my mother told me I belonged in Room 108 with the servants, and I realized she was wrong.”

They laugh, thinking it’s a joke.

I don’t.

Because in that moment, in that hallway with the polished floors and the bad lighting, I saw the whole architecture of my family’s lies lined up like bad wallpaper.

You are poor.

You are nothing.

You don’t belong.

And I understood, with a clarity that still startles me, that the only way those sentences would stay true was if I believed them.

I didn’t.

I moved into Room 108.

I found a letter.

And at dinner, under a chandelier, while they drank wine and laughed at me, I exposed their lies and revealed the truth—about my mother’s betrayal, about my grandfather’s trust, about who I was and who I would become.

Everything after that—the boardrooms, the reforms, the children running through the halls—has been the long echo of that loud, quiet moment.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying And Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud…

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying And Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud… My sister hired private…

AT MY SISTER’S CELEBRATIONPARTY, MY OWN BROTHER-IN-LAW POINTED AT ME AND SPAT: “TRASH. GO SERVE!

At My Sister’s Celebration Party, My Own Brother-in-Law Pointed At Me And Spat: “Trash. Go Serve!” My Parents Just Watched….

Brother Crashed My Car And Left Me Injured—Parents Begged Me To Lie. The EMT Had Other Plans…

Brother Crashed My Car And Left Me Injured—Parents Begged Me To Lie. The EMT Had Other Plans… Part 1…

My Sister Slapped My Daughter In Front Of Everyone For Being “Too Messy” My Parents Laughed…

My Sister Slapped My Daughter In Front Of Everyone For Being “Too Messy” My Parents Laughed… Part 1 My…

My Whole Family Skipped My Wedding — And Pretended They “Never Got The Invite.”

My Whole Family Skipped My Wedding — And Pretended They “Never Got The Invite.” Part 1 I stopped telling…

My Dad Threw me Out Over a Secret, 15 years later, They Came to My Door and…

My Dad Threw Me Out Over a Secret, 15 Years Later, They Came to My Door and… Part 1:…

End of content

No more pages to load