My Mother-In-Law secretly recorded me for three months, claiming I was a terrible wife and destroying her son’s life.

Part One

“These videos will prove everything.”

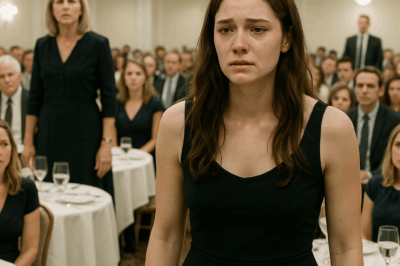

Margaret held the USB drive aloft like it was a sacred relic and not a sliver of plastic, her lacquered nails flashing beneath the courtroom fluorescents. Her voice carried—born to carry—over the scraping of chairs and the quiet rustle of files. She didn’t ask the court to take judicial notice. She didn’t have to. She was narrating for an audience she thought she already owned.

I kept my hands folded in my lap and my eyes on the wood grain of the table. If I looked at the screen too soon, I’d give her what she wanted. If I looked at James—my husband, her son—I knew I’d see the same guarded distance that had settled there since last week, when she’d assembled his siblings in our living room and staged a premiere of my life without my consent.

“Your Honor,” Margaret said, projecting triumph, “I’ve been gathering evidence for months. She’s not the perfect wife everyone thinks she is. These recordings will show exactly how she treats my son, how she’s ruining his life. Three months of footage doesn’t lie.”

Three months. Seventeen cameras. Some lovingly hidden behind picture frames and faux succulents, others tucked into a smoke detector or a floor lamp with a pinhole lens. Some positioned with startling precision in spaces that should belong to no one except the people who share that bed, that office, that breath.

The judge—a man with weary patience and eyebrows like quotation marks—tapped his pen against the bench. “Mrs. Parker,” he said, tone neutral, not unkind, “you’re saying you installed cameras inside your son’s home without the knowledge or consent of either resident?”

“It’s my house too,” she snapped. “I live there.” She turned to glare at me. “I had every right to protect my son from her manipulation.”

James shifted beside me. Not toward me. Not away. His silence hurt worse than her words. I’d been explaining myself to Margaret for eight years. I wasn’t going to start explaining to the judge too. That’s why we had Sarah.

“Your Honor,” said Sarah Bennett, calm as breath, our counsel in a navy suit as unassuming as a scalpel, “before we proceed with viewing any illegally obtained recordings, I’d like to submit my client’s work schedules and hospital logs for the timeframe in question.” She placed a tabbed binder on the evidence cart. “And to note for the record that these cameras recorded my client in spaces where she had a reasonable expectation of privacy. Any such recordings are unlawful.”

Margaret scoffed. “Schedules can be faked. Videos don’t lie.”

The judge glanced at the court technician. “We’ll view the footage. Counsel, your objections are noted for the record.”

I felt my stomach tighten as the first clip appeared on the monitor. There I was, in our kitchen at 5:07 a.m., hair in a low bun, stepping quietly to keep from waking James as I assembled breakfast and a packed lunch, scrawling a note—Have a good day. I love you.—and sticking it beneath a magnet shaped like a banana because Margaret had broken the apple one.

“See?” Margaret leaned forward, voice thick with vindication. “Leaving before he wakes up. What kind of wife does that?”

“Mrs. Parker,” the judge said, a finger lifted, “please refrain from commentary until the clip concludes.”

More footage. Me slipping into scrubs, tucking my badge into my pocket, checking that the coffee machine had water. Me returning twelve hours later, bleary and smiling at the text message that said a child had finally eaten a full meal after weeks of treatment. Me leaving a voicemail for James—call me when you get a chance—when the ward went quiet and my feet ached and the snack machine ate my dollar. Me stepping outside to the postage-stamp garden to call a parent back from a quiet corner so my sobbing wouldn’t wake anyone.

“She’s always on her phone,” Margaret said to the air. “Always. Probably talking to other men.”

In the front row, one of James’s sisters shifted in her seat. Her husband crossed his arms. The tech clicked to the next clip.

In this one, the camera wasn’t on me at all.

Margaret—pearls at her throat, that pearl-white fervor gleaming in her eyes—slid into our office past midnight. She opened my desk drawers one at a time, fingers riffling through immunization record cards and a stack of thank-you notes patients’ families had sent me over the years. One card slid to the floor; she stepped on it without looking down. She pulled my journal from the bottom drawer—the one with the little lock nobody uses after age ten—and flipped it open.

A few rows back, someone gasped. The judge’s eyebrows rose.

“Your Honor,” Sarah said, standing, “the footage appears to capture more than Mrs. Parker intended.”

The technician clicked again.

Now Margaret stood in our bedroom, my journal propped on my nightstand, her phone held inches above it. She snapped photos of two pages, three, four, smoothed one with the flat of her palm, and smiled.

“Mrs. Parker,” the judge said, “are you aware that in this state recording someone in a private residence without consent is a crime? And that photographing private papers is… not protective.”

“I was protecting my son,” she said, eyes hot. “She’s not who she pretends to be.”

James finally spoke, his voice so small the microphone barely caught it. “Mom,” he said, looking at the screen, not at her. “What were you doing in our bedroom?”

Sarah touched the technician’s shoulder. “Please play Clip 17.”

The scene was one I’d replayed in my mind too many nights: a table set for two, a banner made from butcher paper and blue tape—HAPPY BIRTHDAY J!— drooping because I’d realized too late the tape didn’t like paint. I’d made his favorite roast chicken with thyme, roasted carrots, a ridiculous chocolate cake I’d started at four in the morning, trying to fit celebration into a shift-filled life. Candles sat and then leaned and then burned down to wicks.

The camera showed Margaret picking up James’s phone. “Oh, honey,” she purred. “Olivia had to work late again. Go to the bar with Mark. Don’t wait up.”

She put the phone down. The camera caught her wiping two candles clean with a tissue, an expression of small satisfaction on her face.

“Your Honor,” Sarah said quietly, “we’ll submit phone records showing my client never called. And kitchen receipts from that night. And the photographs I took of the cake she kept for three days trying to make the celebration happen anyway.”

James swallowed. “I thought she forgot,” he said, barely audible. “I was… mad.”

Sarah nodded to the tech. “Clip 23, please.”

Margaret in the garden, stone angel behind her shoulder. “Yes,” she whispered into her phone. “Next Friday. The charity gala. Olivia will be working nights. It’s the perfect chance for you to accompany James. Wear the blue dress. The one we chose.” She smiled. “Of course, Jessica. He’s going to love you.”

I’d worked that night until dawn in the PICU, my fingers raw, a little boy’s hands even smaller in mine as we explained a procedure to his parents. James had come home late, smelling like hotel perfume and performative philanthropy, telling me I should have told him if I wasn’t coming. I’d looked at my shift schedule on the fridge and my own reflection and wondered how we’d become a tangle of missed messages.

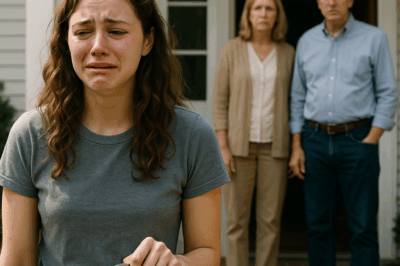

The tech clicked to a clip I didn’t remember because I hadn’t seen it. Me on the living-room floor at three a.m., my scrubs wrinkled, my body bent around the hollow ache of losing a child named Sophie I’d braided hair for while we waited for her mother to sign a consent form. The camera saw my face blur with tears. Margaret stood in the doorway like a movie villain learning a new exit, smirking at my pain and doing nothing to soften it.

Across the room, someone’s chair scraped the tile. Margaret’s expression wavered.

“Mrs. Parker,” the judge said after a long silence, “do you have anything to say regarding the footage showing your… activities?”

“She took my son from me,” Margaret hissed. “She turned him into a man who pours coffee for a wife who runs out the door while he eats alone. She made him proud of her work, not his family. I raised him to expect a wife who is home.”

“In this court,” the judge said, “a wife who saves children’s lives is home—home to herself, home to the oath she took. What you did is not protection. It’s control.”

He looked down at his notes, then back up. “We’re going to take a brief recess. When we resume, I will be prepared to rule.”

The bailiff called, “All rise,” but nobody moved for a moment. James didn’t let go of my hand until the second call.

In the hallway, the air smelled like sanitizer and stress. Lawyers murmured into phones. The technician leaned against the wall and licked a thumb to wipe a smudge from the monitor as if cleanliness could retroactively fix what we’d all seen.

James’s siblings clustered near the far end, unsure whether to approach us. His sister Amanda rubbed her arms like she’d stepped into a freezer. His brother Mark stared at the floor. Nobody looked at Margaret.

When the bailiff opened the door again, we filed back in. The judge adjusted his robe and sighed the way people do when tired of being disappointed.

“Mrs. Parker,” he said when we were seated, “under the circumstances and after reviewing the evidence, I am granting Mrs. Parker—” he smiled faintly, catching the double, “—Olivia Parker’s petition for a protective order. You will vacate their home within twenty-four hours and remain at least five hundred feet from the Parkers, their house, and the hospital where Mrs. Parker works. Further, I’m referring this matter to the district attorney’s office for review of potential criminal charges related to unlawful surveillance and invasion of privacy. And I’m ordering you to attend counseling.”

Margaret opened her mouth, then closed it. Her lawyer put a hand on her arm and shook his head just enough.

The judge turned to James. “Mr. Parker, this court cannot force you to reconcile your marriage. It can only protect people who need it. What you do with your mother is your choice. What you do with your wife…” He let the sentence stand like a doorway. “This is adjourned.”

We didn’t rush. We slid everything back into folders that would smell like stress for weeks. The moment the wood gavel tapped, the room seemed to exhale.

Outside, on the courthouse steps, cameras waited—the press kind, not the ones that make you question the sanctity of your home. Sarah angled us away, efficient, protective. One reporter shouted, “Ms. Parker, did you know about the cameras?” I blinked into the light and said nothing. Some stories don’t belong to the day. They belong to the people inside them.

At home, we worked like archaeologists. We found cameras behind a vent grate, in a wall clock, tucked into the mouth of a porcelain frog on the patio. Seventeen, in total. James unscrewed the last one from a bedroom sconce and stared at it in his palm as if it were a small animal he’d rescued and didn’t know what to do with.

“I don’t know when I stopped seeing,” he said finally.

“You were trying so hard not to see her grief,” I said, folding a towel too many times, “you couldn’t see mine.”

He stacked the cameras in the center of the kitchen table like a tribe we were banishing. Then he reached for me. “You shouldn’t have had to stand there alone,” he whispered into my hair. “I’m sorry.”

We pulled one of the little cameras apart with a screwdriver. Inside, the wires were pretty in a terrible way—like a cruel person could make art of control if given tools. We threw them into a garbage bag in the trunk of my car and drove to the recycling center, where a man rolled his eyes and said, “Again?” like he knew everyone’s family business. We laughed for the first time in weeks. The sound startled me, then warmed the space between us like soup.

The next morning, at three a.m., my phone rang. I beat the alarm by twenty minutes and sat up, already pulling on scrubs. “PICU,” I answered. “Parker.”

“We need you,” said the night nurse. “RSV season just decided to come back angry.”

“I’m on my way,” I said, already sliding on shoes. James had left coffee ready—he always did—and a sticky note: Remember to eat. Love you. I tucked the note into my pocket like armor.

At shift change, I scrubbed out and sat with a parent whose son had made it through the night. She squeezed my hands and cried. It was a good kind of cry, heavy and holy.

On my first lunch break back, Linda from the ward stopped by our table with two chocolate milks and a gossip face. “We don’t like to talk about it,” she said, pulling up a chair, “but half the parents hugged your husband at the coffee machine this week. He looks like a man who learned something hard and is still learning.” She sipped milk like a toast. “He held a father’s hand when he was too brave to cry.”

“He’s trying,” I said, a simple, big truth.

Three months later, a padded envelope arrived with neat cursive I didn’t recognize. Inside, a letter.

Mrs. Parker,

I owe you an apology. I met James at work. Your mother-in-law reached out to me privately and… manipulated me. I ignored my discomfort because I wanted to be chosen. I see now how wrong that was. Enclosed is a USB with recordings she made of our conversations. Use it if you need to. I’m moving. I won’t be a part of this anymore.

—Jessica

I showed James. He sat very still, then nodded and walked the USB to the shredder. We didn’t need more videos. We needed less. We needed to make our own.

We bought a secondhand camcorder from a kid who wanted a better phone and filmed nothing polished: the space between us on the couch on a Tuesday night, me falling asleep with a book open on my chest, James teaching our neighbor’s son how to change a tire. We piled the footage on a hard drive labeled Years We Held Each Other and didn’t watch it. It didn’t need to be consumed to exist.

Margaret complied with the restraining order in the way people do when the alternative is wearing orange. She went to counseling. We heard through James’s sister that she liked the counselor most when the counselor agreed with her and less when the counselor asked her to speak into the parts of the story that weren’t flattering. She joined a grief group and then another one when the first one suggested she could change without collapsing.

Her lawyer called Sarah. Settlements were discussed for the civil suit, numbers scribbled, apology letters drafted and never sent. It was fine. The apology I needed had already occurred in a courtroom with the lights too bright.

On the one-year mark, James and I went back to the courtroom and sat in the back row as a different couple argued about a different mother-in-law and a different boundary. On the way out, we didn’t say “there but for the grace…” We said “we keep learning.” We held hands all the way to the parking lot like teenagers.

Summer arrived hot and full and loud. One evening after shift, we sat in the garden Margaret used to critique. It grew chaotic in ways I found tender—tomatoes where tomatoes had never been planted, basil that had no respect for borders, sunflowers that turned their faces toward us like blessing. James brought two mugs of coffee and a blanket because nurses are always cold when they shouldn’t be.

“You know what today is?” he asked, eyes pretending to be casual.

“The anniversary of the day you saw me,” I said.

He laughed. “The anniversary of the day we took our life back.”

We clinked coffee mugs like champagne and then cried like fools because it’s interesting how joy and grief can hold hands and not let go.

A week later, a thick envelope arrived from the district attorney’s office. Margaret had taken a plea deal on one misdemeanor surveillance charge and accepted court-ordered therapy. The DA’s letter was dry and matter-of-fact. Justice looks like paperwork often. I put the letter in a drawer and then took it back out and put it in a folder labeled Closures because I’m a nurse married to an administrator and we label things even when they’re intangible.

In August, the hospital named me Nurse of the Year, which mostly meant my photo in the newsletter and a parking spot for a month. Margaret would have hated its humility. I loved it like my favorite pen.

I’m not naïve. I know the camera on your life can appear when you least expect it, that your image may be held up for consumption by people who assume they know your heart from a pixel. But I also know this: surveillance is not the same as seeing. A lens can capture you. It cannot hold you.

When we go to bed now, we lock doors out of habit and to tell our bodies they’re safe. We laugh at stupid sitcoms and cry at commercials about dogs. We leave notes on the fridge with magnets that all work, apple and banana and a little stethoscope. We don’t film any of it. We don’t need to.

This is the part of the story where someone expects retribution. A son who disowns his mother. A lawsuit that leaves her penniless. A dramatic public apology. Those aren’t our endings. Our ending is a garden that grew wild and a home that is quiet now in the right ways. It’s the life of two people who choose one another again and again, even when someone tries to hand-deliver a script that says otherwise.

Sometimes, the best revenge is simply this: living a life that cannot be edited to fit someone else’s narrative. A life that withstands the pause button. A love that, even in silence, makes a sound loud enough to drown out any USB drive thrown into the air like a flag.

We took our life back. We live it forward. And no one—not even a mother with seventeen cameras and a script straight from another century—gets to direct it but us.

Part Two

The first real test of the restraining order came on a Sunday in October, the kind of day that leans toward sweaters in the morning and bare arms by noon. I was on the back porch trimming the basil—still unruly, still refusing to learn borders—when I heard tires crunching gravel out front. I didn’t move. The cilantro had bolted and the mint had colonized another pot; that felt like the only urgent thing in the world worth tending.

James stepped out onto the porch and held up a hand. “Stay,” he mouthed, then disappeared through the kitchen. I listened to his voice, calm and firm, and a second voice, hushed and imploring. Then the sound of our neighbor Rick saying, “Ma’am, you can’t be here,” and the soft, patient tone of Officer Martinez: “Mrs. Parker, this is not a good way to show your son you’re making progress.”

Two minutes later, the tires retreated. James reappeared with the sort of smile that only exists to reassure. “She brought a lasagna,” he said, moving toward me. “Handed it to Rick like it was a grenade with cheese.”

“And?”

“And he took it and walked it straight next door.” He made a face. “I don’t want to commodify the work of our local raccoon population with that thing in our fridge.”

I wiped my hands on a towel and leaned into his chest. He smelled like coffee and sawdust; he’d been patching the porch rail all morning. “Thank you,” I said, feeling the relief, yes, but also how it layered with something sturdier. Not dependence. Partnership.

He kissed the top of my head. “We’ll keep doing this,” he said, “as many times as it takes. Boundary. Breath. Basil.”

“Basil,” I agreed, grinning.

Margaret complied more often than not, and when she didn’t, the world stepped in the way of her worst impulses: neighbors who stood where she could not, an officer who called the counselor rather than the jail when she showed up sobbing at the curb, a DA who understood we weren’t trying to ruin a life—just to live ours without someone else filming it.

We didn’t follow the gossip of what she said at church or to her bridge club. We said yes to the counselor’s invitation to a single session—not family therapy, but a mediated, structured boundary conversation—eight weeks after the order went into effect. We met in a beige room that had tried its best to be a forest: fake ferns, a watercolor of trees, a sound machine whispering something that wanted to be a river.

The counselor, a woman in her fifties with a mouth like a seamstress—tight when sewing, soft when done—set the rules. “You may speak from your own experience,” she said. “You may not tell someone else what theirs is. You may ask for what you need. You may not demand what they cannot give.”

Margaret perched on the edge of her chair as if the session might be over faster if she never fully sat. “I was grieving,” she said, eyes not on us but on some memory. “When my husband died, the house wasn’t quiet. It was loud, like all the noise he used to make was still there, but it couldn’t turn into words.”

“I believe you,” I said, because it was true and also because I wanted to say something true before I said everything else.

She glanced at me, surprised, then looked down at her hands. “I wanted… I wanted you to be who I was. I wanted you to make dinners at five, and fold shirts like my mother folded shirts, and ask me what I thought first because I never got to say anything before.”

“We can’t be your do-overs,” James said, voice gentler than I could manage. “We can be your son and his wife. That’s all we can be. That has to be enough.”

She nodded around the words as if they were a table she wasn’t sure she had the right to sit at. “I’m sorry,” she said, and it didn’t sound like the courtroom. It sounded like she’d peeled letters off her tongue to make it, like it cost something.

“We’ll keep the order in place,” I said. I didn’t raise my voice. “We’ll let the counselor coordinate any contact. We’ll revisit in six months. That’s what I need.”

Margaret blinked, pain and understanding wrestling under her skin. The counselor nodded. “That’s a boundary,” she said, smiling like a teacher who’d just seen a student finally use the right word. “Not a punishment.”

We collected our coats in silence. Before we stepped into the hall, Margaret said, “He pours coffee for you every morning.”

“Yes,” James said, his mouth turning upward.

“He used to drink black,” she muttered, as if telling the carpet something important. “Now he buys oat milk.”

“People change,” I said softly. “Sometimes for the better.”

We built rituals to steady us. Tuesday night garlic bread. Friday morning walks around the block where we told other people’s dogs they were good and meant it like a prayer. Sunday afternoons when I folded laundry on the bed and James read aloud whatever book he was trying to make me love: quiet histories, loud novels, a collection of poems about rain.

We also built a paper trail of our own choosing. Not insurance notices and court filings—though we kept those, too—but a folder labeled Grace Notes. We printed emails from a mother whose son’s asthma finally stabilized and from a father who wrote that James’s calm at the intake desk made him feel less like he was handing his child to a system and more like he was handing him to a person. We tucked in a Polaroid of the night we put the couch at a forty-five-degree angle and agreed the room had been wrong for years and we just hadn’t known how to say it.

One afternoon in December, a nurse manager asked if I’d speak to a state committee about hospital safety and privacy. “Your story matters for more than us,” she said over an apple that kept squirting juice onto her scrubs. I laughed, still not used to being the pitcher for someone else’s metaphors.

I wrote my testimony in the garden, in the kitchen at 2 a.m., in the car in the hospital lot with the heat blasting my ankles. When I looked up at the committee dais months later and saw a row of faces that had never met a gossip magazine they didn’t secretly enjoy, I breathed slow. Breath. Boundary. Basil. I told them about the patients and the people who care for them and why you cannot function when you suspect someone might be making entertainment of your grief. I did not say Margaret’s name. I did not say Jessica’s. I said we. I said home and meant both.

A week later the committee asked me to consult on draft language tightening penalties for unlawful surveillance in private dwellings. “If your mother-in-law had a doorbell camera and filmed your front step, that’s one thing,” a staff attorney told me. “But in a bedroom—” she shook her head, angry enough to spill her coffee. “People need a line.”

“Not just a line,” I said. “A fence you need a permit to move.”

We left the legislature that day and bought ourselves the dumbest celebration: two hot dogs from a cart whose owner called everyone boss. We ate them in the car, laughing because mustard shouldn’t ever feel like punctuation, and yet: there we were, spelled in joy.

Jessica moved to a city two states away. Sometimes grace looks like distance. She sent one more letter, not with an apology this time, but with a photograph: a child life specialist at a pediatrics unit where the walls were painted resplendent, where stuffed animals waited on carts like little nurses. I didn’t become a nurse, she wrote in looping script, but I found a way to borrow some of your courage. Thank you for not making me pay for the worst version of myself forever.

I pinned the letter inside Grace Notes, sticky-taped the edges because I knew we’d read it until it tried to escape.

In February, the hospital held its annual gala—the one that had become commentary rather than celebration last year. We debated skipping it. Then we bought thrift-store suits and told ourselves we’d leave if the napkins were the wrong kind of fancy.

I saw Margaret across the room. She wore navy—the same shade as the counselor’s carpet—and stood near the door like a person making sure she had an exit. She did not approach us. She made small talk with a volunteer coordinator and laughed at a joke that looked like it hurt. She didn’t throw wine. She didn’t even throw a glance.

Halfway through the speeches, the photographer came to our table. “Nurse Parker,” he said, patting his camera like a pet, “the foundation wants a picture of the people who built the new family room.” He gestured to a poster on an easel: THE SOPHIE SUITE in memory of a little girl whose mother wanted other parents to have a good chair to wait in.

James and I stood. Margaret stepped back to give the camera a clean shot. I looked at her in that small half-second and saw it: the mercy of being able to stand and not need to run. I inclined my head. She inclined hers. If a nod could be a treaty, it was.

By spring, the restraining order expired. We left it that way. You can file the paper again, but our fence now lived elsewhere: in calendars mediated by the counselor, in “no” spoken before a sentence grew teeth, in a reservoir of laughter that belonged to nobody’s edits.

We saw Margaret in public sometimes. Once at the farmer’s market, hands full of beets, swearing under her breath about dirt. She did not try to wipe mine on my apron. Once at the library, her voice at a volume appropriate for the space. “Your testimony,” she said in the biography aisle without a greeting, “helped a woman in my senior group. Her daughter-in-law thought she was losing her mind. It was a camera.” She swallowed. “They are… healing.” She looked at the carpet like it might hand her a better word.

“I’m glad,” I said. Then, because the counselor had insisted praise is not love but it can be a handrail, I added, “I hope you’re healing, too.”

She smiled, a small, strange twist like a seam being unpicked slowly but correctly. “I’m learning to drink my coffee black again,” she said. “Oat milk is for the young.”

“You’d be surprised,” I said, grinning.

On a Saturday in May, James and I hosted a backyard picnic for the unit. No donors in suits. Just scrubs and sandals and a toddler army. The sun slouched toward evening and the basil tried to climb a tomato cage, insubordinate as ever.

Linda climbed onto the porch step and clinked a glass with a spoon. “We rarely do speeches,” she said, “because people who work our hours get hives with anything that looks like tradition. But today we have cake and cake requires context.”

Laughter. Nurses require laughter like oxygen.

She looked at us, at the people holding paper plates, at the kids chalking rainbows onto the patio. “This year we’ve lost and saved and lost again. Some of us were under cameras. Some of us were the cameras for each other when we needed to be seen. I’m proud of that, and I’m proud of you.”

She gestured toward the house. “Also, your kitchen labels are a thing to behold. Who color-codes cumin?”

“I do,” I said. “Do you want it to elope with cinnamon? Because that’s how chaos happens.”

The cake was strawberry and ridiculous. It tasted like a truce with the world.

After everyone left, the yard looked like joy’s aftermath: plastic cups in the grass, a lone sock on the steps, a fresh crayon melted to the patio table in a rainbow smear. We cleaned up slowly, letting ordinary goodness replace what the year had taken.

James folded a lawn chair and tucked it into the garage. When he turned back, he leaned in the doorway a second and just watched me gather napkins. “You know,” he said, “when I think about all those months under a camera, I don’t remember what she wanted me to. I remember how you made this a home. With notes on bananas. With basil that refuses to behave.”

“We both did,” I said. “With coffee and oat milk.”

He laughed and kissed me, then nudged my shoulder. “Tomorrow I’m making pancakes.”

“With sprinkles?”

“With sprinkles,” he promised.

We went inside and locked the door out of habit and for the small child inside all of us who wants click sounds to mean safety. I slid the bolt and turned to him. He put his forehead to mine. “No more films,” he said.

“No more films,” I agreed.

Only a life, and the kind of silence that doesn’t hurt—one filled with breath, and basil, and the small un-filmed ways people choose each other every single day.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. CH2

The Silence Of My Parents Hurt Worse Than Her Words—They Let Her Crush Me. Part One The room was…

She laughed in my face, claiming i was never legally married to her son. CH2

She Laughed in My Face, Claiming I Was Never Legally Married to Her Son Part One When people talk…

Why do you hate your parents? CH2

Why Do You Hate Your Parents? My parents kicked me out for getting a job and not being able to…

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was Rich. CH2

The Day My Parents Kicked Me Out With A Suitcase… Was The Day The Lottery Hit. By Dawn, I Was…

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way. CH2

At Brunch, My Mom Smirked “You’re Lucky We Even Include You—Pity Goes A Long Way” Part One They chose…

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left. CH2

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left Part One In…

End of content

No more pages to load