My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career

Part One

They were a tidy sort of family when it suited them—neat faces at Christmas, measured smiles at graduations, the sort of group photos that could have been airbrushed right out of a catalog. I used to think those photos told the whole story: two parents who’d tried, three children who’d somehow stayed connected. In the frame, everyone looked content. In the small moments between the frames, things were messier.

My name is Euphemia Brennan. People call me Fi. I make a living diagnosing risk and building order out of chaos. It’s what you do when you spend your twenties learning how to read numbers and human patterns in the same breath: you learn to trust structure. You learn to make contingency plans. I did my internships in the cavernous, fluorescent world of investment banking, learned to speak in figures and projected returns, and then, after years of work and a stubborn streak that often masqueraded as simple stubbornness, I launched a fund with partners who liked my instinct and were willing to back it with capital. People in my circles said things like “tactically brilliant” and “has an ice vein in the right places.” The kind of language that makes one accept a five-year-old birthday party invitation with a practiced smile and a private exhaustion.

And then there was Daphne. She is older than me by three years. She was our family’s weather—always predicting thunder clouds when none were on the horizon for anyone else. You could say the house favored her; it often did, though not through any discreet conspiracy. My mother, Pat, has always been particularly tender with fragility. She calls it compassion; sometimes it felt to me like a magnifying glass that amplified any sadness that tilted in Daphne’s direction.

Daphne was, from the beginning, a good story to tell. When she failed calculus in high school, she was “fragile.” When she dropped out of a community college course, she was “finding herself.” Whatever misfortune happened in her orbit, my parents rearranged the furniture of the household to accommodate it. If a man left her, someone would pick up the pieces. If a landlord turned stormy, someone would hand over their credit card. Love in that household often meant supply, not confrontation.

I grew up trying to be worth somebody’s worry in a different way: I made lists and checked them off. I studied late into the night, did internships, sent thank-you notes, and the map of my life slowly filled with colleges and job offers like a city planting new streets. I thought—naively—that if I built everything carefully and held it up to the light, the family would gather around it and admire the view. Pride is an odd, human currency; sometimes it circulates freely, and sometimes people with it hoard it.

When I was first promoted at twenty-five, the family’s reaction was the textbook of polite confusion. “Isn’t that a lot of hours?” my mother asked over mashed potatoes, glancing at my résumé like it might disfigure the silverware. “You can’t be too busy, Fi. Family still matters.” I learned to smile and say the things you say to keep dinner comfortable. It was easier than being the fist in the room.

The trouble started in small accelerations. Daphne married, divorced, remarried in a way that made hush fall over Christmas cards. Babies came and left fathers the way autumn sheds leaves. She moved back in with Mom more than she left, and my mother, who had once seemed like a moral anchor, began to function as a kind of soft institution for Daphne’s needs: storage of clothes, a holding pattern for tantrums, the place where grievances were aired like linens, admonished, ironed, put back out.

I loved Daphne in those years with a sibling’s complicated tenderness—protective yet exhausted. She could look at the world as if it had broken her personally. Once, when she confided that someone had snubbed her at a playdate (a capital sin in her eyes), our mother canceled her afternoon plans and carried casseroles to that house in a fury of offended maternal protectiveness. My presence, a piece of the modern world with its suits and its cold coffee and its relentless travel schedule, became abrasive. I remember the exact tone of one Sunday afternoon—my mother clasping her hands like a prayer, her eyes on Daphne, and saying, almost apologetically, “Fi, try not to bring up work. Daphne gets anxious about it.” The message was clear: shine elsewhere, dim here.

You learn to accept many indignities if they’re gentle and consistent. But there was a red thread in the same fabric: in front of visitors, Daphne’s fragility was a story to be told, and I, with my promotions and articles, furnished the antagonist. If I came into the house with a new coat or a mention of a business trip, it wasn’t an achievement in their telling. It became currency to show someone where they lacked, to say, by comparison, “Look at how lucky Fi is. Look at what she has.”

Two years passed in this rhythm. I tried to keep things even. I bought my nieces hand-carved night-stands from London, the sort of odd, thoughtful gift that felt like doing something right. At a cousin’s birthday, Daphne told me I was “splashing money in people’s faces.” At another event my father tried to talk to me about a tax problem in a tone that suggested I should be grateful to be included in the household’s fiscal weirdness.

Then came the Thanksgiving I remember from the doorway.

I had driven six hours, because I always drove. The road between my life and my family was negotiable by car; by heart it wasn’t. I arrived with a dish wrapped in foil and a suitcase of clothes. I expected the kind of ferocious warmth that families can sometimes manage when they run low on logic and reach for ritual. Instead I found my mother at the front door, hand on the knob like a sentry.

“You’re not welcome here,” she said flatly, blocking my path with an authority calibrated to end conversation.

I stood in the mud of a New England autumn and looked at her. For a while all my words collected like rain in a gutter. “Pat, I told you I’d be here. It’s Thanksgiving.”

She didn’t falter. “I told you not to come. Daphne needs space right now. Your presence is triggering for her.”

I remember the way the words felt like a physical pressure in my chest—as if someone had put a lid on a kettle. “Everyone else is in there,” I said. “They’re fine.”

“They don’t upset her the way you do,” she replied, voice tight. “You don’t understand the toll this takes. She cries for days after you visit. She needs this.”

At that moment a dozen different responses rose in my throat, games of logic and humiliation. But none of them made a sound. My mother had made a decision that would be tidy for her conscience: make me an absence rather than confront her daughter’s problem. It was a small, neat solution. Exile by decree.

I stayed in a hotel that night and ate room-service turkey alone. The house’s lights burned like someone else’s life. My phone died with no one calling except Damian, who texted, “Sorry, sis. Mom’s doing what’s best. Maybe Christmas?” and a string of heart emojis that read like a plea. That was my first major measure of cruelty: it’s one thing to be excluded, and another to watch everyone adjust to the idea of your nonexistence without a second thought.

People at work call it resilience. People who don’t get the rest of your life call it stoicism. I felt both and neither. I kept working. I kept meeting numbers, attending dinners where the menu was a metaphor and the waves of conversation rose and fell like financial markets. I started a second fund. I watched my bank account swell in quiet increments, as if money could measure self-worth. It didn’t. There were awards and dinners—Faces and Forbes and panels—and as I stood at podiums and took questions about scaling teams and risk mitigation, I’d sometimes imagine my mother watching from a quiet room with the kind of pride that loves objectivity but spurns the subject.

Two years passed in this shrunken arrangement. Birthdays blurred into conference calls. My mother sent postcards sometimes, with awkward messages: “Thinking of you,” “We miss you,” “Hope you’re well.” I found those notes in my apartment and I shredded them on the subway, then in the dizzying evening I felt guilty and cried for ten minutes in a public bathroom. You can do all these things at once in this life: keep your funds afloat and bleed quietly into the sink.

People, as I have noticed through years of looking at patterns, have a soft spot for a crisis. When the crisis arrives the village gathers; when the grief is habitual the village wanders off, exhausted. For Daphne, the public calamity arrived one gray Tuesday morning when the news feed lit up with the words “Welfare Fraud” and a photograph of her, hair scraped back, eyes like two small marbles. The government had found irregularities. Names. Returns. A shadow-accounting of life.

At first I refused to believe it. The idea that a person we’d cushioned, mothered, mended, could be spinning a web of lies that stretched into federal departments felt absurd—like finding a crack in a perfectly glazed teacup. Yet the proof soon stacked: checks to addresses that didn’t exist; receipts that didn’t reconcile; testimonies from caseworkers that read like a novel of incredulity. She had been collecting benefits under multiple names and claiming children for households in which the children were not present. The total was astronomical—over a million dollars, the reports said. The word “scheme” leaked into televised reports like a bad odor.

The first time I saw her face on the evening news, my stomach dropped like a stone. There was no performative anguish—no rehearsed claim of innocence or careful staging of charity. There was a photograph, then a caption, and then my life contracted into a tiny, efficient column of responses. My assistant called and asked if I’d be offering a comment. I declined. This was not my circus.

The family who’d chosen to speak for Daphne for years suddenly had to speak about her criminality. My mother, who had been so fierce in defense of her daughter’s fragility, called, and the sound of her voice made the floor tilt. “Fi,” she said quick, with that panic that has a particular nasal edge. “We need you. Can you come? The house—there’s been a raid. They’re asking about tax returns.” There was a hammered rest of the word “please” in there, like someone trying to pry open a stuck jar.

I remember staring at the phone, the quiet lobby outside my building, the rain pinpricking the cab windows. Memories unfurled like lamps: the day I flew home with a wooden toy for a nephew and got accused of “showing off;” the Thanksgiving in a hotel room; the notes in my hand that said “We miss you” like something left at an unswept altar.

I did not go. I had rehearsed a refusal for weeks now, in the calm quiet that comes when you realize you’re not being given back your dignity. I sat on my couch and drafted a reply to my mother that used the language my industry had taught me—sentence forms like frameworks, references to responsibilities and legal counsel, a note that said, plainly, “Mom, I cannot help.”

In the days that followed, the story unravelled in spectacular slow motion. Daphne was indicted. The hearings were footage-heavy and humiliating. She was charged with fraud—systematic and grievous. The scale of the theft made it news, made the sort of gossip that travels like tumbleweed between the local courthouse and the supermarket. My mother’s name got dragged like a net. She had been asked about how such a thing could happen under her roof; she had to explain the patterns and lapses. Their savings were depleted covering legal fees. My father withdrew from phone calls that once had lots of love in them until the words were skeletal. Damian—my twin—called once, voice thin and shamefaced, to say they were sorry and needed help.

There was a small, fierce point of satisfaction I will be honest about—the kind of moral arithmetic that people think is mean until they are on the receiving end. The family who had exiled me because I reminded them—through success—of what they lacked, now had to live with the consequences of their choosing. I felt something like vindication. The night the indictment came down I poured myself a large glass of wine and watched the news. It felt oddly like watching a bad weather report; you know storms happen but rarely are you pleased to see a wall of water crest.

But vindication is a narrow thing. It doesn’t warm you; it sharpens you. It doesn’t bring back two Thanksgivings alone in hotel rooms. It doesn’t return a childhood. I allowed myself the rare indulgence of satisfaction, then closed the laptop and got back to work.

They asked for help. They asked me to come. They asked me to forgive. My mother sent letters—actual envelopes, handwriting like a map of regret. She wrote: “Euphemia, I was wrong. I see now that I chose the story I wanted to believe rather than the truth. Please come. We need you.” I read it three times. It sat like a hot coal in my palm. Words are cheap; absence can be more costly.

I did not ignore them out of hatred. I measured instead. How do you raise a hand to pull someone out of a pit when they had built it and pushed you aside? My answer was that I would not be the people’s depository again. I would be generous, on my terms, to the things that aligned with my values. I returned a letter explaining as carefully as if I were making a contractual offer: I would provide funds for a lawyer on the condition that it be transparent; I would contribute to the children’s education but only under circumstances that would not allow the money to vanish into a sieve of excuses; I would not give a single penny to an adult who had chosen a path of deceit. I signed with my initials and sent it by tracked mail.

My mother replied with a single sentence on a cheap paper napkin one night—“It’s not about money, Fi. It’s about family.” But in their world, family had meant something different: limited to presence in a room, not to moral reciprocity. They had wanted me physically in the living room as a talisman of success while tolerating Daphne’s long pattern of deception. My presence had been an emblem; their forgiveness, I realized, was a symbolic currency they were out of.

In many ways, the story could have ended there: dramatic exit, financial admonition, mutual exiling. But life is not a tidy script. There was a turning point that carried me further than mere retribution.

Part Two

After the indictment, a peculiar, slow collapse happened. The house that had once been an anchor became a physics experiment in loss. Legal fees ate up savings like moths on wool. Mom sold the house as an effort to consolidate assets, a transaction that made the neighbors shake their heads and pass by with slow sympathy. Daphne went to trial. She was found guilty and sentenced to several years. The spectacle of her mugshot—eyes flat, cheeks flushed with the flush of being seen—was the kind of public humiliation that novels sometimes reserve for villains; to us, she was merely human, and that made the fall much more tragic than any plotline.

My mother’s calls became less certain. She who had once stood at the door in a crisp cardigan declaring me unwelcome now left voicemails with trembling consonants. She had, in her own way, been a footnote in the book of Daphne’s choices: enabler, perhaps, but not the author.

There is a point in almost any falling kingdom where the people inside start to look for someone to blame other than the king—they look outward. That’s where I drew the line. Damian, who had once advised compromise as if a truce was the same thing as truth, came to my office with a folder and dark eyes. He wanted help. He was asking for practical things—advice on how to reorder accounts, contact information for a bankruptcy attorney, ways to secure guardianship for the children while his sister served time. He said the words, “We made mistakes,” as if confession could be currency. Again, I measured.

I went back, not out of pity but because I have always believed in the utility of certain duties. Human beings require scaffolding to remain upright; sometimes scaffolding is not the same thing as surrender. I met them in a lawyer’s office. I arranged for a trust for the children’s education that required oversight and accountability. I insisted that any agreement be iron-clad, with audits and trustees and reporting lines. I insisted that contributions be made through intermediaries with clear purposes. They balked—they wanted a single check, something easy and ceremonial. “No,” I said. “Ceremony has its place. So does responsibility.”

It took months of negotiation and shame and paperwork. My mother lost much and learned a different kind of humility. She started to work at a grocery store, that small, honest labor that brings in slow steady returns and strips away the pretense of entitlement. She came to my city a few times for court dates. Once, when I saw her in the courthouse corridor, she looked older, smaller, and her eyes met mine with something raw and unadorned. “Fi,” she whispered. “I was so stupid. I thought love meant sheltering. I see now I was enabling a lie.”

“Then let’s repair,” I said. Repair is not the same thing as returning to old patterns. Repair requires labor, and repayments with interest.

Daphne’s sentence was severe for reasons both practical and moral. She had taken money meant for the truly needy. The men and women who worked in state offices and charities had to witness that betrayal. She was convicted, and the system closed over her like a door. I have never been to a prison yard, but, through the routine of visits and letters that seeped through legal channels, I met the new reality that was my sister’s life: letters with shaky script, admissions that read like a ledger of regret.

When she finally wrote to me, the letter arrived in the winter like a thin bird. “Fi,” she began, “I did terrible things. I thought I was protecting my family. I thought I was clever.” Her words were jagged and honest. I replied not with the hot rage I had once carried like a blade but with a structure: three pages that said if she was willing to accept responsibility, to repair what she could, to enter treatment and counseling, I would assist with educational funds for the children and support for the family’s reconstitution. If she wanted to weep and do nothing, I would not fuel what had been a machine for excuses.

The months that followed were slow and sometimes ugly. There were court hearings about restitution, civil suits, and then the practical dismantling of the family capital: homes sold, possessions scattered, the private economy displaced. There were nights when news trucks gathered like vultures, and my mother, once a person who loved the spotlight of being right, now avoided it like a room that suddenly smelled of rot. She started to come to terms with the difference between love and capitulation.

Through all this there was a thread in my life I did not expect—the possibility of chosen family. I had colleagues who were not colleagues but friends who would arrange dinners by saying, “Fi is in town. We’ll have a little thing.” There was a woman at the fund, Veronica, who came over with lasagna and said in that frank way only close friends do, “You don’t deserve this, but you didn’t need to be the hero nobody asked for. You could be the sister you kept, instead.” She introduced me to people who loved structure and contributed warmth: men and women who were messy and human and could accept generosity without weaponizing it.

A curious thing about surviving is that the more robust your outer life becomes, the less you hunger for the validation of those who once set the table. I found delight in the small rituals of my own home: the way a pot can simmer properly, the exact tilt of the hand when you pour olive oil into a pan. Those things became dearer than the applause of a room that had once excluded me.

The family implosion continued on other fronts. My father, who had been conflict-avoidant his whole life, retired early in disgrace and started to volunteer at a library. He discovered that arranging books had the same gentleness as reconciling with sons. Colin, the peacekeeper, moved across the country and found a kind of contentment that is earned in exile: neighbors who made him soup, a job that asked for calm and hands. Damian tried to knit the family together and occasionally succeeded; more often he failed and then learned a new humility in the attempt.

The question that few people asked—and which I had to answer for myself—was whether forgiveness was optional or obligatory. Every culture has a catechism about family. The one I grew up with said: you show up, no matter what. But showing up, I learned, can sometimes mean passing on the path of a liar and enabling a crime.

When Daphne was released, four years later, she came back to a different landscape. Mom had a small apartment. Dad lived in a studio. The old house had been sold after repossession hearings. Daphne had letters and a new rhythm of resignation. The first time she walked into my kitchen after it had been all but impossible, she cried like someone who had been bereaved not of a person but of a life. I did not jump to embrace her. I sat her down and asked about the children. She spoke about them in terms that were fierce; she loved them with a passion I acknowledged. But love without accountability is a dangerous thing.

We met in a neutral place at first: a café that had a windowsill long enough for three mugs. She apologized with a slow, human sorry that had grown from humiliation into a kind of contrition. I listened. I watched a woman who had once been a dramatic presence shrink into the thinness of a person who had learned the limits of performance.

“Fi,” she said in a voice that was a paper-thin thing. “I have nothing to ask for except…if you have room for me once I’m trying. If you can accept that I am trying to rebuild, I would like that.”

I thought about the nights in a hotel room, the dinners alone, the letters shredded. I also thought about a child asking, once, at the bottom of a stair, “Why is Aunt Fi not in pictures?” The question had lodged like a fishhook. “If you are sorry,” I said, “then let your actions prove it. Show up to therapy. Pay restitution. Let the children know the truth. Help repair the accounts. I will help them directly in ways that cannot be intercepted.”

She agreed. Her first steps were clumsy and public. There were times when she would slip and cry and call me in the early morning and ask for advice on a bank transfer or to tell a story that might explain a missing payment. I answered sometimes, and I set boundaries always. The rules were simple: transparency, work, restitution. If she lied, the bridge would fall. If she honored the work, the bridge would be a place to pass things back and forth again.

My mother watched. She had aged in a way that made me ache; she was a woman whose moral compass had been compromised by love and who was now learning the cost of enabling. There was no easy redemption for her. She wrote me a last letter in which she said: “I see now that I was wrong. You were lonely and I abandoned you by making you smaller. I am sorry for that. I do not expect you to return to the way things were. I only ask one thing—that you know I was wrong.”

I forgave her, in the modest way you forgive when you are not saying you will forget. We started to visit each other in small increments. I would bring a pie. She would bring an awkward casserole. The awkwardness was honest, which made it, unexpectedly, more durable.

What surprised me most in the aftermath was not how the family fell apart, but how I found new families in my chosen life—friends who celebrated wins, a partner named Gregory who loved my stubbornness and hated the injustice of what my family had done, colleagues who called in the middle of the night because they had some ridiculous idea about improving the world. I built a life where my success was a tool to create the conditions I valued—supporting women founders, funding scholarships, making room for other people to shine. My funds began to invest in companies that normalized domestic care labor, that made it possible for parents to keep careers and children to grow without the economic constant of sacrifice.

There were days when I woke up with an ache that felt like missing an appendix. The family photo albums looked like mockeries because they had all the people who were in them and had nowhere to put me. But the ache softened. Loss is something that time arranges into territories that can be visited like landscapes; you mark the boundaries and you continue to live.

One crisp spring afternoon, when my lavender had finally settled into a happy neighbor with the bees, my daughter—one of Daphne’s children, grown and sturdy and not entirely unspoiled—came to my office with an acceptance letter clutched to her chest. “Aunt Fi,” she said, voice high with joy. “I got into a program I love.” She wanted to move to a city where opportunities were not a legend. I wrote her a check and then called her mother and told her to teach the girl how to make a strong pot roast. That night, I sat on the balcony and thought about the strange ring of consequence.

The legal system had a shape to it: you pay debts, serve time, sometimes try to reenter the world. There is no magical unmaking. My sister had spent years spinning a fragile narrative in which the world owed her compassion, and the world, in its slow machinery, had demanded an account. The family who had sheltered her had to pay too: for mortgage payments, legal fees, loss of reputation. Their choices had led to consequences that were not intuitively distributed; they were messy as life always is. I had a ring of clean counters in my kitchen and an office that hummed with the sound of other people’s trust. I had a quiet soul and a hard-earned sense of what I would accept and what I would not.

Sometimes people ask if I regret my firmness—if keeping the door shut for two years while the family unraveled felt cruel. My answer now is stable and strange. I do not regret the boundary because boundaries are the framework for healthy relationships. If you give yourself to people who will exploit you and then expect you to maintain the show, you will lose more than you can count. Setting the boundary did not give me joy; it gave me the possibility for a life uncoerced. It gave me the power to say yes on my terms and no on my terms. That is not cruelty. That is something that looks a lot like survival.

When Daphne came home, we met perhaps the way strangers do who share a hard history. She scraped at the layers of shame and constructed a new set of rituals—sober visits, therapy, restitution payments. They were small at first, then larger. At her first family dinner after she had worked a year with a counselor, her eyes were clearer. She looked at the children and read them a book; she had a kind of tentative joy I recognized as trying. Not all stories knit back together; some remain frayed. Ours was reweaving.

And my mother? She learned to say “I was wrong” without a pile of words after it. Those three words fell out of her mouth like seeds that took time to grow. She worked odd jobs. She learned the routine of a day where your dignity is now your own wage. It was humbling, and there was an unglamorous grace in it. I attended some of her small theatrical community events because she started volunteering at the library’s reading hour and the old woman who once balked at my life now licensed joy again in small, domestic ways.

As for my own life, I kept the stubbornness that had brought me here and added a steadier measure of softness. I began to mentor young women in finance, not because I wanted applause but because I did not want someone else to show up in a room with their success and be pushed out. I invested in companies making childcare more affordable and workplace cultures that support families not by singling out the fragile but by creating equal structures. That felt like paying back the debt with interest.

In the quiet end of it all—the place where endings curl up like leaves—I found a small truth. Family is not simply the people who share your blood. It is also, and perhaps more importantly, the people who choose you in the messy business of life. You can be born into an account and still be overdrawn. You can choose, in the little acts, to be someone else’s refuge. I chose that for strangers, for friends, for nieces and nephews who asked me to bake a cake and not to be their judge. I chose, finally, to accept that my mother may have been wrong; I chose to accept her apology when it was honest. I chose to rebuild, cautiously, the house of us, brick by slow brick.

If you ask whether I had to lose two years to learn this, the answer is yes. The price of being whole again is sometimes measured in the absence of applause. The family who once made me small had to live the consequences of their choices. Daphne had to pay an enormous public price and then learn how to live with the private work of being accountable. My mother had to learn that kindness without truth is cruelty.

And me? I marched on. I kept my fund. I built scholarships. I made space. I let the life I had constructed be a place for others. When my mother, finally, sat at my table and asked me to teach her how to use a spreadsheet so she could balance a tiny household budget, I did it. We laughed at the first ridiculous formula she made. It was a small, bright triumph.

In the end, the question people often pose—would you dim your light so someone else wouldn’t be jealous?—has a clear answer for me now. I will not switch myself off so that someone else’s insecurity can be soothed. The only lights I am permitted to dim are those I choose to lower to make room for others to shine. If someone asks you to make yourself smaller for the sake of their comfort and the cost is your presence at a table, say no. If the ask is come together, do the hard work, pay the debts of complicity, then perhaps the table can be set again for supper.

The house is still a home now, noisy with different voices. Sometimes I go back for holidays. Daphne sits across from me and offers the occasional honest smile. My children—figurative and literal—run across the yard. My mother brings an awkward casserole. I chop the parsley. We have learned to tolerate the rough edges and to say, plainly, when something is not allowed. It is not the family I imagined in a neverland of perfect plates, but it is ours. It is honest.

The last time someone asked me, in a speech for a charity event, whether I believed people could change after hard falls, I said yes: people change if they have to, and if they choose to. I said also that sometimes the people who change do not come back to the same chair at the same table. They build new sets of rules. They learn to ask for help without weaponizing someone else’s success. If you hold your light careful and true, it will not burn anyone else out; it will illuminate a path where others can learn to set their own lamps upright.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

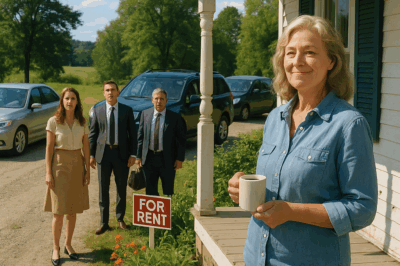

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour… CH2

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour, I’ll be there…

MY BROTHER BROKE MY RIBS. MOM WHISPERED, “STAY QUIET -HE HAS A FUTURE.” BUT MY DOCTOR DIDN’T… CH2

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She…

MY BROTHER-IN-LAW ASSAULTED ΜΕ- BLOODY FACE, DISLOCATED SHOULDER MY SISTER JUST SAID”YOU SHOULD… CH2

My brother-in-law assaulted me — bloody face, dislocated shoulder; my sister just said “You should’ve signed the mortgage.” All because…

Parents Lied To Me About The Day And Time Of Our Flight So That I Would Miss Our Trip To Hawaii… CH2

Parents Lied To Me About The Day And Time Of Our Flight So That I Would Miss Our Trip To…

Sick Wife Alone at Home, Husband Partying Abroad – ‘Get Better, I’m Busy’ → Trip Ends in Surprise. CH2

Sick Wife Alone at Home, Husband Partying Abroad — “Get Better, I’m Busy” → Trip Ends in Surprise Part…

My son and his wife kicked me out SIL said, ‘Live with us ‘ Me ‘Really !’ Unexpected ending. CH2

My son and his wife kicked me out SIL said, ‘Live with us ‘ Me ‘Really !’ Unexpected ending. Part…

End of content

No more pages to load