My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration

Part One

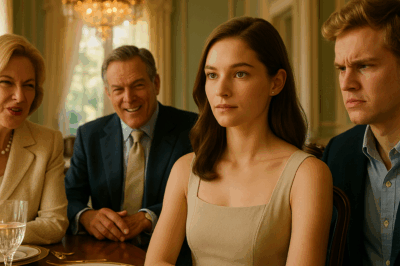

When my mother raised her crystal flute at the Raleigh Convention Center and said, “To the daughter who deserves it all,” the room swelled the way a room does when it longs to be part of someone else’s beautiful story. Two hundred people—judges and partners and men whose ties cost more than my rent—lifted their glasses and turned their faces toward my sister, soaking in her reflected light.

I did what I had been trained to do since childhood: I smiled small, swallowed a feeling that could have been pride if it didn’t hurt so much, and tried to choose a face that would not ruin anyone’s evening. From my spot at a satellite table near the freestanding coat rack—distant cousins, a neighbor who remembered me as a toddler, a senior partner’s wife who kept calling me Christy—I could see the head table like a stage. My sister, Willow, sat in the middle beneath a canopy of white roses, her silk dress catching every warm beam a lighting tech could coax from the rig. On her right was her husband, Jonathan Wood, Raleigh’s favorite son of the year: a thirty-five-year-old founder with a post-IPO smile and parents who collected museum wings the way other people collected Christmas ornaments. On Willow’s left, a fraction closer than etiquette allowed, sat David Marshall—firm partner, rainmaker, rumor with cheekbones.

My mother—Diane Parker, fifty-six and, in certain circles, a verb—held the microphone like a weapon she preferred to a blade. “Nothing rivals a mother’s joy in her child’s triumph,” she said, glancing at Jonathan’s parents as if their approval were oxygen. “From Duke’s top honors to the youngest partnership in Raleigh’s finest firm—my daughter has conquered every challenge. With the perfect partnerships, her empire is unstoppable. To the daughter who deserves it all.”

The applause that followed could have been mistaken for weather.

I’m Crystal Parker. I’m thirty. I make a living designing identities for companies that don’t know who they are yet and reminding them that a logo can’t fix a lie. In our family, “solid” isn’t a compliment; it’s dismissal with good manners. I grew up three years behind Willow in a house where success was a spotlight with exactly one bulb. My father, Edward, fifty-nine, kept most of his feelings shelved neatly next to his ethics textbooks; when my mother performed love like a victory lap for my sister, he would sometimes lean across a table to tell me the ribs were good or that he liked the way I’d drawn the tree on my homework, as if his tenderness should be smuggled.

The pattern was as reliable as a metronome. When Willow brought home certificates, my mother turned them into wall décor. When I brought home art, she filed it. At sixteen, my sister got a convertible with a bow; I got a secondhand laptop that I was grateful for and used to design half the student council’s flyers. Willow’s Duke Law graduation was a ballroom; my UNC design degree was a diner and a mother who kept checking the weather as if it could change in time for her to notice me.

If you had asked any of the people in that convention center to describe our family, they would have called us close-knit or impressive or the kind of people who know how to throw a party and mean it. They wouldn’t have known that my mother had chosen her speechwriter months ago—a woman named Lisa Bennett whose daughter had an unblemished LinkedIn and a name that fit well in my mother’s mouth—and that my contribution to the evening, beyond the fresh hell of the seating assignments, was to proof the signage for typos because “you’re good with words, dear.” They wouldn’t have known that when I asked if I could design the event’s visual identity, Willow smiled in a way that didn’t touch her eyes and said, “We’ve hired a professional firm for that. You stick to the small stuff.”

And they certainly wouldn’t have known what I had seen in the months leading up to this night. The way my mother steered Jonathan away from David whenever the men drifted toward each other at cocktail parties. The way Willow’s texts coming in at odd hours had shifted from the frantic joy of a woman making her own luck to the brittle vigilance of someone who had learned to call the chessboard “love.” The way my father started drinking his first bourbon before the sun went down.

Here is the thing about being overlooked: you either learn to see everything or you learn to stop seeing at all. I chose the former. So when Willow made a toast at my father’s fifty-ninth—“To the man who taught me never to take no for an answer”—and brushed David’s cufflink when she handed him the mic for his speech, I took my phone into the hallway and stared at a beige carpet until I could breathe again. When I passed the small conference room outside the ballroom and saw Willow and David pressed to either side of a cream curtain, their heads tilted toward each other, their laughter too careful, I did what my work had taught me to do: I opened the voice memo app and let thirty seconds of truth gather itself.

I didn’t go to the celebration at the convention center planning to set anyone on fire. I went with my low-heeled shoes and my faith that I could last one more night without becoming the kind of woman who made a fool of herself in front of busy men. I took my seat with distant family and a woman who wanted me to guess which judge had left his wife, and I watched my mother lift her glass and say, “To the daughter who deserves it all,” and I felt something I had been swallowing since I could say the word sister drag itself back up my throat until it took the air my lungs were trying to use.

“I have something to say,” I heard myself tell the room.

The murmur that followed was almost tender. The microphone arrived in my hand with a weight that startled me.

“I’ve watched Willow win at everything since we were children,” I began. A hundred faces arranged themselves into what they thought was empathy. “From debate trophies our mother polished until you could use them to see your future, to the Duke degree we celebrated for months, she has mastered the art of getting what she wants.”

Beside my sister, my mother’s mouth flickered with the first hint of alarm. Lisa Bennett sat still in a silver dress, her speech in her lap, her usefulness evaporating.

“What amazes me most is her philosophy on success,” I said. “She once told me, ‘Partnerships—business or marriage—are just deals. Trust is for fools when power is on the line.’”

Someone in the second row made a sound people make when they realize they forgot where the exits are. Jonathan turned his head toward Willow like he had misheard something in a language he thought he spoke.

“You’ve given her everything,” I told him. “Your network. Your name. Your patience. But some deals come with costs hidden from those who trust the most.”

“Crystal,” my mother hissed from the middle of the room. “Sit down. This isn’t your moment.”

“Then make it mine,” Jonathan said to her. “Let her finish.”

I lifted my glass—a prop I had not needed all evening—and said, “To Willow’s triumph. May the truth behind it shine as brightly as her crown.” I turned the glass in my hand and saw David’s reflection jump. He had flinched.

There are two parts to any good reveal: the words and the timing. I had both. As the applause turned choppy and thin, I slid my phone from my clutch and hit send on the message I had built like a small, discreet bomb: screenshots of Willow’s texts with my mother, outlining how to leverage Jonathan’s contacts for a five-million-dollar deal; the photo of my mother’s tidy handwriting on a legal pad that read, Wine with Judge R.—ask for his nephew’s firm to get a seat at the table; and that thirty-second hallway video, the one where Willow said, “Keep him out of it; his circles will only slow us down,” and David said, “After the papers sign.”

I sent the bundle to Jonathan. To his parents. To my father. To three senior partners who had known Willow since she debated in a navy blazer with sleeves too long for her arms. I had also slipped the tech assistant fifty dollars and a smile during setup to make sure the projector would be ready to “fix a loop issue” exactly when I said so.

The DJ called for cake. The towering confection rolled in on a cart draped like a parade float. My mother corralled the photographer. “Angles that show the crowd,” she said. “Angles that show the family.”

Willow lifted the knife. Her hand shook once. Jonathan reached to steady it. The room sighed like it had forgiven me for my interruption because sugar and spectacle restore order.

Phones vibrated and birds took flight—one sound after another, like the overture to a production nobody had paid for. Jonathan looked down at his screen. The color left his face in a clean line.

“What the hell,” he said, too softly for the room and loud enough for Willow. He turned to her and held his phone up like a mirror.

My father’s phone chimed. He put down his glass. I watched my mother’s mouth whisper No three times without making a sound.

The projector blinked to life with all the innocence of a machine doing what it was asked to do. The screen above the stage flickered—one second, two—and there we were in the grainy hallway footage I had titled for me: my sister’s hand on David’s sleeve, their heads bent together like conspirators in a play. Keep him out of it; his circles will only slow us down. After the papers sign.

The sound that rose from the crowd was not laughter and not a gasp. It was the noise a room makes when it drops the glass it had been holding and watches it break in slow motion.

“This can’t be,” Jonathan said, voice losing vowels, face losing grace. “Tell me this is fake.”

“It’s a hack,” my mother hissed, already turning to the closest senior partner with a script she could sell. “Anyone can doctor a video.”

“Ask her to show you her phone,” I said. There are choices I regret in my life. That sentence is not one of them.

Jonathan did not wait for permission. He opened the side door Willow had used earlier to slip off for lipstick, found David in the small room off the ballroom with his tie in his pocket and the color of a man who had lost his best bluff, and hauled them both back by the collars of their suits.

“Explain,” he said, holding his phone up so the room could see the blue and gray confession of months. “Explain using the word respect if you can find it.”

Willow’s mouth did the thing a mouth does when it is excellent at arguing and has just realized arguing is a bad plan. “It’s taken out of context,” she said. “I—this is—Crystal is—”

“Showing me,” Jonathan said. He took his ring off the way you take off something that has burned you and placed it on the table with a sound that became a sentence. “We’re done.”

“Jonathan,” Willow said, reaching. He stepped back. David reached for her hand and then thought better of it and looked for his tie instead.

My mother found her voice. “We can fix this,” she said, as if the evening were a spreadsheet and she had found a typo. “We move the cake. We call the DJ. We—”

“You coached her to deceive me,” Jonathan said, his anger losing its polish. “You treated me like a business development strategy.”

My mother turned on me then, the old fury back and beautiful in its way. “You’ve destroyed your sister’s life out of jealousy.”

I took a breath so the words would come out clean. “No. I destroyed the lie. Your life did the rest.”

The room emptied itself the way rooms do when a person they thought they were supposed to admire becomes a cautionary tale. By the time the staff started cutting the cake—practical people doing practical work—the head table had learned how to be small.

I drove home through a Raleigh that looked sincere without lighting designers. I did not shake until I was in my kitchen with my shoes off and my hands around a glass of water. My therapist would later tell me that you cannot undo thirty years of swallowing spits of anger in one evening without nausea. “You’ll feel both proud and sick,” she said. “That’s your body remembering what boundaries taste like.”

For the first time in my life, something I did because of who I am—not because of who my mother needed me to be—had moved a room.

Part Two

The morning after, the Raleigh Journal replaced a profile of Willow with a photograph of a cake and called it “The Party Where Truth Was Dessert.” The reporter tried for clever and hit cruelty, but the story inside got almost everything right: youngest partner, carefully choreographed celebration, glitch in the production, a video nobody wants to see of themselves played above a cake they cannot cut.

Jonathan filed for divorce in a handful of days—the sort of clean cut that men with very good lawyers prefer. His petition didn’t rehearse moral philosophy. It listed attachments: texts, a video, a witness list that included a tech assistant with fifty extra dollars in his pocket. His parents issued a statement about valuing integrity, which is what people like them say when they’ve paid for it and still believe they own it.

Willow went to work at the firm on Monday morning and discovered that even people who like winning do not enjoy losing in public. She kept her job because money loves money, but the five-million-dollar contract her strategy had built collapsed under the weight of vendors who suddenly discovered scheduling conflicts and contacts who no longer returned calls. David grew difficult to find.

My mother called me the names she had saved for me since I was old enough to threaten the mirror. “Jealous.” “Petty.” “Ungrateful.” My voice mail filled with a chorus of her particular mastery: defending my sister as if the truth were an enemy we should all agree to kill. I blocked her not because I wanted to punish her but because there is a difference between forgiveness and exposure. You can forgive a person and still insist on fresh air.

My father knocked on my door with a canvas bag full of groceries I didn’t need and a sentence I did. “I failed you,” he said without rehearsal. “I let your mother make you small because I thought love meant peace. I was wrong.”

We sat at my tiny kitchen table with a bowl of apples between us like a prop from a play about the simple life people don’t actually choose. “You stood up,” I told him. “Now we see what that means.”

What it meant, that first week, was a suitcase in the back of his car and a new key on his ring. What it meant after that was a new apartment that smelled like paint and a lawyer whose office didn’t have carpet you could sink into. “Your mother’s world is built on control,” he said, hands wrapped around a mug of coffee like he was learning how to warm himself. “I can’t live in it anymore.”

My phone became a place for old cousins to become new friends and strangers to become brave. The internet loves a scandal; it loved ours for about forty-eight hours and then moved on. But the people who sent me messages at two in the morning were not there for gossip. They were there to tell me what it had cost them to stop being invisible to their mothers. I answered as many as I could without dissolving.

Work figured itself out in a way I didn’t expect. My boss, a woman who had started the agency in a garage that still smelled like oil, read the story and sent me a text that said: Do you need a day? Do you need two? Also, we need you to present to the city next week; can you come tell the truth about their logo the same way you did last night? I did. It went well. We won the contract. I made twice my rent in a bonus and used the money to buy a lamp that makes my apartment look like it can hold the kind of light that used to make me flinch.

Therapy helped. Dr. Susan Reed did not congratulate me for being brave so much as she congratulated me for stopping. “You don’t have to perform strength,” she said. “You can choose it. Some days you can also choose to stay on the couch and eat cereal for dinner. Both are allowed.” She helped me name things I had thought were weather: my mother’s condescension, the way Willow’s success had been used as a weapon against me, the way my father had chosen quiet over intervention until it cost him his marriage.

Jonathan’s mother called me. She had the voice of a woman who had learned to be gracious and decided not to resent it. “You saved my son,” she said simply. “You broke my heart a little, too. But you saved him.” I thanked her. It was more complicated than that. It was also exactly that simple.

Willow sent one email: You’ve always hated me. I hope you’re happy. I didn’t reply. I wanted to tell her I had never hated her, that I had hated the way my mother loved her like it was a victory over me, that I had hated the way we had been turned into a zero-sum game. But emails like that ask for a fight you cannot win.

The house I had grown up in became my mother’s museum—empty rooms staged for people who stopped coming. The Barton Street house where my father moved filled with things that belonged to him because he had chosen them: a secondhand couch that did not have plastic on it; a cheap coffee machine that whistled like old cartoons. He bought a dog because he had wanted one for thirty years; he named it Lucky because the world still needs jokes.

At some point in those first months, I realized I was not performing being alive anymore. I was just… living. I made playlists that included songs that did not impress anyone. I learned to make arroz con pollo from a YouTube video and then made it four more times until my hands remembered it. I bought a plant that needed me once a week instead of twice a day. When people asked me to do favors at work that the junior designer could have done, I said, “No,” and then said, “Because,” and watched my colleagues learn faster without my quiet competence cushioning them.

Six months later, I cooked dinner for six in my apartment. My father came with Lucky and a pot of chili that smelled like he used to smell when he came home from work and dropped his briefcase on the floor on a Friday as a promise. Two friends from the agency came with a bottle of wine that I did not drink and a cake I did not eat but did cut for them because the world is bigger than my diagnosis. My cousin Tara brought a pie and a story about how she had told our aunt to stop calling her “the smart one” in a way that made her kids think their mother’s love was a competition.

“To Crystal,” my dad said, lifting his glass of water. “Who taught me that peace without truth is just quiet.”

I felt something unspool in my chest that might have been hope.

There are things that deserve to be told plainly, without choreography. My mother filed for divorce on the grounds that my father had betrayed her by choosing me. He said, “I chose honesty.” The judge, who did not know our family and did not need to, split their assets the way the law demands it. Lucky has a schedule and a bed in both places. My mother found new people to impress. Sometimes I see her name in a fundraiser invite and feel a flicker of the old panic and then remember I am allowed to sleep.

Willow stayed at her firm. She kept winning cases. You can be good at a thing that does not make you good. But she stopped coming to the family Fourth of July. At a holiday party I showed up at because Tara promised me it would be safe, I saw her across a room and we nodded at the same time. That was all. I don’t know if it was enough. It was what we had.

On the anniversary of the night I took a microphone and stuck a hand in the machinery of my mother’s favorite story, I woke up before the alarm and went for a run because I am a cliché who found moving her body helps her be a person. Raleigh looked like forgiveness. I don’t think it was. It was just a city, doing its job. But it made space for me in a way it hadn’t before. That’s something.

In the afternoon, I walked Lucky with my father and we passed the convention center. The glass doors reflected two people and a dog and not a single person with a plan for their children. My father said, “Do you regret it?”

I thought about cake and sugar and a hand on my shoulder and a voice that said, “Sit down, this isn’t your moment.” I thought about Jonathan’s ring glinting on a white tablecloth and my mother’s mouth forming the word family like a weapon. I thought about my sister’s face when she realized arguments couldn’t save her and my father’s voice when he said, “Crystal did what was right.” I thought about the messages at two a.m. from women who said they stood up the next morning because they saw me do it the night before.

“No,” I said. “I wish it had gone differently. But I don’t regret telling the truth.”

He nodded. “The worst parts of my life started with me not saying anything,” he said. “The best parts started when I did.”

Therapy has taught me endings are not fireworks; they are decisions repeated. So here are mine, small and daily, that make up the big one you probably came to the end to find: I do not answer numbers that hurt me. I do not build myself into a bridge for people who want to lay on me like a lounge chair. I design things that make sense and I ask to be paid what men are paid. I have dinner with my father on Thursdays. I do not go to my mother’s. I forgive my sister in increments based on evidence.

I have stopped waiting to be toasted.

In case you need it the way I did: you are allowed to stand up when someone gives a speech that erases you and say, “I have something to add.” You are allowed to time the truth for a moment when lies are the loudest so that people cannot pretend not to hear you. You are allowed to walk out of a room that shames you and build a life where honesty is not an interruption but a foundation.

At the convention center, my mother lifted her glass and said, “To the daughter who deserves it all.” A year later, my father lifted a different glass and said, “To the daughter who demanded the best of us.” I didn’t cry at either. I didn’t need to. I had already learned the thing the toast was trying to grant me: my worth didn’t require permission.

If you ever find yourself in a room where love is measured out like cut cake, stand up. You’ll shake. People will stare. The DJ might fumble. In that awkwardness, you will feel your life change shape beneath your feet. And then you will go home—to a small apartment or a big one, to a dog or a child or your own company—and you will make dinner, and you will sleep, and you will wake up to a world where the next thing you build will be yours.

That is not vengeance. That is freedom.

END!

News

My In-Laws Invaded My Dream Home — So I Arranged A Special Delivery That Made Them Permanent… CH2

My In-Laws Invaded My Dream Home — So I Arranged A Special Delivery That Made Them Permanent… Part One…

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was. CH2

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was… Part…

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… CH2

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… Part One The pen…

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… CH2

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… Part One The…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… CH2

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… Part One The…

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load