My Mom Refused to Believe My Son Was Mine — 6 DNA Tests Later, She Started Packing Her Bags

Part 1

The fluorescent lights of the hospital room hummed, casting a thin, antiseptic glow over everything. I was nineteen and hollowed out by thirty hours of labor, when the nurse tucked a warm, squirming bundle against my chest. He was perfect—ten tiny fingers, ten tiny toes, a full head of dark hair and skin the color of warm caramel. My heart did that dangerous thing they warn you about in parenting books, the free‑fall inside your ribcage that feels like joy and terror and oxygen deprivation all at once.

“Hi,” I whispered, because anything louder would have shaken me apart. “Hi, Eli.”

The door opened with a practiced knock that didn’t wait for permission. My mother, Penelope, stepped in, forty‑seven and immaculate even in a hospital corridor. Her blonde hair was slicked into a severe bun; her lipstick sat precisely within the borders of her mouth. She crossed to the bassinet, eyes skimming over Eli, then me, then back to him.

“He’s quite dark, isn’t he?” she said—polite voice, knife edge.

I pulled the thin blanket higher around him. “He’s got my hair, Mom. And Archer’s nose.”

“Archer is white,” she said, still not looking at me. “Our family is white.”

The words should have bounced off sense—my father was Black, I am biracial, the math isn’t calculus—but I was split open and sleep‑starved and her voice has always found the soft places to press.

“He can’t be yours. Not with skin like that.”

The air left the room like someone had opened a window to space. I tucked Eli closer and my arms shook. The nurse made a careful retreat, closing the door so gently it didn’t latch.

“Mom,” I said, and it came out a rasp. “What are you saying?”

“You know exactly what I’m saying, Vivian.” Blue eyes sharp as copier glass. “You were careless. And now you’re lying.”

For a second I thought I might drop my son. I wanted to scream that genetics aren’t loyalty tests, that her own grandchild was proof of a history she pretends not to have. But all I did was hold him tighter, shield him with my body from a gaze that felt like a winter draft.

Home was worse.

Her house—the one she insists is ours—has always been curated within an inch of its life: white hydrangeas in glass cylinders, coffee table art books no one opens, a bowl of green apples that seem never to ripen or rot. That first week back, Eli’s cries threaded through the rooms and Penelope’s silences grew a second skin. Every floorboard creak felt loaded. Every closed door settled like a judgement.

She didn’t fight me. She never does directly. She called cousins on the house phone and practiced pity like a monologue loud enough for me to hear in the nursery. “It’s just been so difficult,” she sighed into the receiver. “Vivian’s confused. Poor thing. She doesn’t know who the father is.”

The group chats I used to live inside blinked themselves dim. Invitations evaporated. The messages that did come were weaponized sympathy: We’re praying for you. Sometimes these things happen. God has a plan. My son had colic, my stitches burned, and shame—hers, not mine—swept through our family like a rumor with perfect timing.

Archer lasted three visits. Then there was a family emergency, then a double shift, then silence. His name stopped lighting up my phone. Eli cooed at the ceiling fan while I learned how to fall asleep in ten‑minute shards.

I am not sure when the exhaustion hardened into resolve. Maybe it was the day I passed the nursery and heard my mother’s whisper outside his door—“This… this is shame”—the words hitting the paint like mildew. Maybe it was one of the nights when Eli wouldn’t let my body go, and I watched the sky lighten thread by thread and realized no one was coming to rescue us but me.

I ordered a DNA kit at three in the morning with the kind of steady hands I wish I’d had when I was eighteen.

The first envelope arrived two weeks later. I swabbed my cheek, then Eli’s, carefully—no milk on the swab, no stray fibers. I filled in forms, tapped out our names as if the act itself could anchor us to truth. When the results came, the envelope was thick, officious. I was ready to take it to her and say, Read. See. Stop.

She came down the stairs while I was still skimming the summary. I slid the packet beneath a stack of magazines. She picked them up, at random, with the same careless precision she applies to everything that isn’t a mirror.

The branded envelope slipped, white against white. She clocked the logo, the return address, me.

She didn’t open it.

She crushed it in one manicured hand, walked to the stainless‑steel trash can, and let it fall. The hollow clatter at the bottom of the bin was weirdly loud.

“Those things are silly,” she said, brushing her palms together as if she’d dusted a shelf. “Anyone can buy them online.”

It wasn’t dismissal. It was contempt—for evidence, for me, for a grandson she refused to see. That sound in the trash can was a door locking in my head.

Fine. Not one test. Six.

I used the money I’d been saving for a community college summer class I don’t even remember wanting and turned our kitchen table into a lab bench. AncestryDNA, 23andMe, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, LivingDNA, and an academic lab Archer’s cousin had used once for a paternity dispute—I ordered all of them. I tracked shipping like people track storms. I logged every barcode number, photographed every vial in Eli’s hand because the ritual made me feel competent.

The results trickled in. One by one, the same chorus, different phrasing: parent‑child match. 50% shared DNA. Ethiopian and West African components evident in both mother and child. Family networks threaded between us like kintsugi—the gold fill in the breaks.

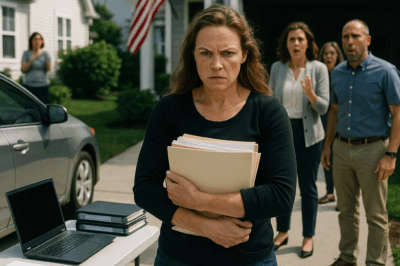

I built a binder because paper is proof in houses like my mother’s. White spine, clear sleeve, tabbed sections. I labeled it ELI’S TRUTH because I wanted to see the words every time I opened it. Screenshots, PDFs, certified copies arriving with raised seals, a log of the dates she called me confused to people who used to babysit me for free. I printed more than I needed, because a part of me knew that eventually evidence would have to exist beyond my word.

When I placed the Ancestry report on her nightstand, right next to her reading glasses and the monogrammed hand lotion she buys in bulk, she didn’t even sit down.

“Science gets things wrong,” she said, and did not pick it up.

She walked around the binder like it was a spill on the rug. And still—still—I felt the smallest, most dangerous impulse to convince her. So I did what I should have done from the beginning. I stopped trying to win her. I started documenting her.

And, at night, I wrote to my son.

The journal is green, college‑ruled, the cheap kind with flimsy cardboard covers. I kept it in the sock drawer under Eli’s onesies because it felt like a hiding place a story might trust. For Eli, I wrote on the first page. For when you’re curious or angry or both. For when you need to know that love is not the same thing as telling the truth, but the truth helps love breathe. I wrote what she said, and how it felt, and what time the light hit his face and made his hair look like a halo we didn’t ask for.

The attic box was an accident and an inevitability.

I went looking for the pastel blanket she saved from when I was a baby, the one she likes to mention whenever someone says she doesn’t have a sentimental bone in her body. The storage closet has the pull‑down stairs folded against the ceiling like a secret. A draft breathed dust onto my face when I tugged the cord. Up there, light slanted through a grime‑webbed window and turned everything sepia. I found Christmas decorations and a broken humidifier, a box of letters tied with ribbon—performative nostalgia—and, shoved back against the rafters, a carton so heavy it scraped my palms. DO NOT OPEN, someone had written across the lid in thick black marker a lifetime ago.

The twine had gone crisp with age and snapped under my fingers. I opened the lid and something ancient—paper, perfume, and denial—rose out and wrapped around my head.

Photos first, crisp at the edges and butter soft in the middle. A girl smiling like she didn’t know she’d practice not smiling for the rest of her life. Long dark hair, a messy joy in her posture, a face I knew like my own in a version I’d never met. Penelope. Next to her, arm around her waist, a Black man with crinkled eyes and a low, patient grin. Handsome in a way that made you look twice and then a third time to figure out why your chest was a little warm.

I flipped. The two of them on a stoop with paper cups, laughing mid‑motion. The two of them holding hands, nobody pretending they didn’t. The two of them with a little girl perched on his knee, braids slicked with oil, and my mother’s mouth replicated on a smaller face. I didn’t recognize the house. I recognized the feeling: the uncurated part of someone’s life.

Beneath the photographs: a birth certificate, folded and refolded until the creases threatened to give up. Penelope Marie Edwards. Date. Hospital. Mother: Clara Edwards. Father: Leonard Davis. My breath snagged.

Edwards. Not Quinn. Leonard Davis. Black. My grandfather.

There were letters beneath that, tied with ribbon the way people tie up hope. The handwriting was elegant, almost smugly so. Dates from the late sixties spilled into the seventies. The words passing and dangerous and safe appeared often enough that I stopped and pressed my fingers into the carpet to ground myself in something that wasn’t ink.

At the bottom sat a small, leather‑bound diary. I shouldn’t have read it. I did. My mother’s hand, younger and more rounded at the edges, poured across the pages in careful curls. She wrote about Leonard, about the way he listened and how his laugh came out of him without checking itself first. She wrote—and here the pen dug deeper into the paper—about Clara, about keeping secrets to hold onto respectability, about the easy doors whiteness opened, about train tickets and names and new lives that start with lies because you’re told that’s the price of safety.

Between pages, brittle and waiting, a letter in a different hand. The script was stiff, the tone not. If they find out, it’s over… You are a Quinn now. You are white. If they find out about Leonard, about them, it’s over. Signed: Clara.

We have a word in our family for the way Penelope moves through rooms: composure. Holding the letter, I realized the better word is performance.

At the very bottom, under postcard stacks stamped in places I’ve never been, a Polaroid slid into my lap. I almost missed it; time had curled it into itself. I flattened it gently with my palm. A bus in the background—Greyhound, destination window flickering Celler County, GA—and in front of it, a very young Penelope, seventeen at most, her hair long and her hand at the small of her back like she’d been walking all day. Her belly rounded beneath a loose dress. Pregnant. My mother has always told me she met my father in college. Married at twenty‑one. Baby at twenty‑two. I was nineteen, holding proof that timeline was made of smoke.

I checked the baby monitor in my pocket. Eli slept in a soft, wheezy rhythm that untied and retied my spine. Celler County, Georgia. I’d never heard of it.

I put everything back in order, the way a thief would who intends to steal again.

Her family is a web. I called a strand.

Delilah Davis—forty‑four, my mother’s estranged cousin—lived somewhere two towns over if the old directory in my grandmother’s desk could be trusted. The number miraculously still worked.

“Hello?” Cautious, but not cold.

“Hi.” My voice came out too soft. I cleared it. “My name is Vivian Quinn. I’m Penelope’s daughter.”

Silence, then a small, rueful laugh. “Well. That’s a surprise.” A beat. “What can I do for you, Vivian?”

“I found some things,” I said, and in the mirror over the console table I watched myself decide not to apologize for it. “A birth certificate. Letters. Pictures. A name: Leonard Davis.”

A sigh that sounded like someone letting a secret out of a tight dress. “So she finally told you.”

“She didn’t,” I said. “I found it.”

“Then good for you.” A pause like a blessing. “Yes. Leonard is—was—your grandfather. My uncle. Clara’s husband. It was an open secret with us. Your mother… she wanted a different life. Clara pushed her toward passing—called it safety. We called it shame.”

“And Celler County, Georgia?” I asked, the Polaroid burning a square against my thigh.

“She stayed with an aunt there for a while,” Delilah said. “Seventeen. Eighteen. Came back with a new name and a plan. I didn’t ask questions. People got disowned for less.” The sound she made wasn’t quite a laugh. “What are you looking for, honey?”

“Truth,” I said. “Enough of it that my son doesn’t grow up inside somebody else’s hiding.”

Delilah’s voice softened. “Then you’re already doing better than most of us.” She hesitated. “Your father… I don’t know those details. Only that there were always gaps in the story big enough to drive a bus through.”

We spoke for forty minutes. She told me about Leonard’s hands, about the way he could fix radios and fences and the hurt in a person’s shoulders without making you feel observed. She told me about Clara’s fear, about how fear turns into rules and rules turn into cages if you let them sit long enough. When we hung up, I sat at the kitchen table and stared at Eli’s bottle drying on the rack and decided that if my mother loved cages, she could keep hers. My son was going to have air.

The plan came together like all good plans do—slowly, then all at once.

I borrowed a high‑resolution scanner from a friend in the design department at the community college. I spent nights digitizing everything I’d found: the photos, the letter from Clara, the birth certificate with its raised seal, the Polaroid’s grain. I adjusted contrast carefully and let the scratches remain; truth shouldn’t look brand new. I built a timeline on clean white paper: Penelope Marie Edwards, born 1976. Leonard Davis, Black. Clara Edwards, white. Polaroid, circa 1993. Celler County, GA. Name change. Marriage to David Quinn, 1997. Eli born, 2024. Six DNA tests.

I re‑printed the lab reports. I made a separate section for screenshots of text chains and group chat whispers my cousin Amy forwarded me from the family’s private threads—We’re keeping Vivian in prayer. Penelope says the baby…—with dates and timestamps and the names blurred enough to be decent and clear enough to be undeniable.

I bought a brick of manila envelopes and a brand‑new black pen. On each front I wrote the name of a person my mother cared about impressing: Aunt Jennifer (the let’s not get into that collector), Uncle Steve and his wife, the cousins who stopped liking photos of Eli’s toes after the first week, the neighbor who prays for everyone else’s soul at book club. I tailored the contents to the audience. For the stubborn, more documents. For the curious, more photographs. For the kind, the timeline and one picture of Eli with a note: Meet your cousin.

I didn’t include a letter from me. I wanted the evidence to speak in the voice my mother hears best—cold, official, irrefutable.

I mailed them from three different post offices over two days. It felt criminal and righteous. It felt like making a thing real by putting it into the world.

The first replies came fast.

Vivian, what is this? from a cousin who once brought me a prom corsage because my date forgot.

Is this… true? from Aunt Jennifer, the text blinking and then followed by another: Please call me.

From a number I didn’t have saved—I always wondered about your granddad. She never let me talk about him. I’m sorry, sweetheart.

A handful were pure fury: How could you do this to your mother? And one or two were exactly what I expected from the people who think silence is class: nothing at all.

Through all of it, Penelope moved like a woman in a museum, careful not to brush against the art.

Until the envelope with her name on it slid through our mail slot.

I was making formula while Eli flapped his hands at his mobile. She picked up the stack of bills and catalogs, thumbed them into order, and froze. Penelope Davis Quinn in my hand on the front. For a second, I thought she’d rip it up the way she did the first test.

She didn’t.

She opened it. She slid out the contents, slow as if they might bite. The restored photograph sat on top: Penelope at twenty with Leonard Davis at her side, both of them bright with a happiness that had never been allowed to age properly.

All the muscles in her face stopped doing what they’d been trained to do. Her mouth parted. Her eyes glassed over. The color left and returned to her cheeks in one tide.

She put the photo back in the envelope like a person handling a loaded weapon and left the kitchen without speaking.

I didn’t follow. For the first time since I was a kid, I understood how she uses silence. And I decided to use it better.

That night, Eli slept hard, mouth open, fists loose. At midnight, I heard the soft mechanics of a life uprooting itself: a suitcase hinge, drawers sliding, the barely‑there thud of shoes placed carefully in a line. I got up and cracked my door. The light in her room was on. She moved methodically, folding, choosing, not looking in the mirror.

I closed my door and leaned my forehead against the wood and let the strangest feeling wash over me: grief for a woman who chose a lie so entirely she thought it was oxygen. Then anger welled up to meet it and the two canceled each other out like a math problem that ends in zero. What was left was a steadiness I hadn’t known in months.

In the morning, her phone screamed itself hoarse on the kitchen island. She didn’t answer. Messages stacked in the notifications window—Call me. This can’t be real. Penelope? She moved past them and into her room and came out with a suitcase and a tote bag. She didn’t glance at Eli in his bassinet. She didn’t look at me.

At the door, her hand paused on the knob. She turned her head, just enough to catch me in her periphery. For the first time in my life, her eyes held nothing I could use—not anger, not triumph, not even disdain. Just a blankness like a stage after the audience goes home.

She walked out.

The latch clicked. The house exhaled for the first time in months.

My cousin Amy knocked five minutes later, as if we’d rehearsed the timing. She had a baby blanket in her hands, homemade and too bright. She didn’t ask about the envelopes. She didn’t ask where Penelope went. She stepped around the suitcase tracks on the entryway tile and went straight to Eli, who woke, blinking, and offered her a slow, gummy smile. She picked him up with the gentleness of somebody who understands breakable things.

“She’s really gone,” Amy said, not quite a question.

“She is,” I said. My voice surprised me by not shaking.

Part of me wanted an ending with fanfare—apologies pressed like flowers between the pages of regret, a confession at family dinner, some public, cinematic collapse of a facade. What I got was quieter and meaner and more honest: a woman who had spent her life performing whiteness making an exit in the only way she knew how—without saying the line she was never going to say.

I put water on for coffee. The kettle began to hum. Eli grabbed Amy’s necklace and held it like a talisman. My phone pinged and pinged and pinged. I let it.

I had a binder on the table. I had a box in the attic whose contents had stopped being secrets and started being history. I had a son who would grow up knowing exactly which parts of him came from who. I had questions left—a bus, a county in Georgia, a father whose name might not be the one on my birth certificate.

I had time.

Part 2

Penelope didn’t send a new address. She didn’t leave a note. The only proof she’d been a mother in our house—beyond the tasteful fruit bowl and the silent rooms—was the divot a suitcase wheel left in the foyer rug and the dent in the trash can where the first DNA report had landed like a verdict.

For a week, the doorbell kept churning out people who didn’t know what to do with their hands. Aunt Jennifer arrived with a ham like it was currency for absolution. Uncle Steve stood on the porch, hat in hand, and whispered that he’d always suspected something but suspicion isn’t the same as courage. My phone bloomed apologies and defenses, confessions that used the word complicated like a bandage.

Amy came every afternoon and took Eli outside to watch the leaves shiver. He had learned to giggle—an honest, surprised sound that cracked my chest open in the gentlest way—and his laughter made our fence look less like a boundary and more like a trellis.

At night, when he finally gave in to sleep, I opened my binder and my journal and the scanned folder labeled ATTIC — RESTORED. I looked at the Polaroid again, the bus window stuttering Celler County, GA, and my mother’s hand on the small of her back like she was steadying more than her body. The picture made a noise in my head I couldn’t ignore. Whatever else I had excavated, this was a fault line running under my own name.

Delilah answered on the second ring.

“Do you know who lives in Celler County now?” I asked, no preamble left in me. “Aunts. Anyone who’d remember that time.”

“Some of us,” she said slowly. “My mama’s cousin, Bernice—she’d have been your grandmother’s age. There’s a pastor’s wife who keeps records like they mean something. What are you thinking, Vivian?”

“I’m thinking,” I said, looking at Eli’s soft profile on the baby monitor, “that the story I was given doesn’t balance out.”

We drove down on a Wednesday that had the decency to be clear. I packed too much—diapers, wipes, an extra outfit, two bottles, a backup pacifier for the backup pacifier—and Amy laughed and then didn’t, because she recognized packing like that: a hedge against the suddenness of life.

The highway unspooled. Fields replaced billboards. Celler County turned out to be less a destination than an accumulation of smaller nouns—gas stations, porches with swings, a courthouse whose clock had given up keeping time, a diner that smelled like bacon and disappointment.

Bernice’s house sat under a pecan tree like it had been born there. She opened the door with her shoulders squared and her mouth already grim. Then she saw Eli’s eyes and something in her face loosened two notches.

“Lord,” she said, and her voice softened, “you’ve got Leonard’s look.” She turned that softened gaze on me. “And you’ve got his stubborn.”

We sat at her kitchen table and drank sweet tea that made my teeth ache and sifted forty years out of a Tupperware bin. Church programs with names circled. A newspaper clipping yellow as toast about a bus accident outside town. A photograph of Clara at a bake sale, smile stitched a little too tight. And—carefully, like it might be wrapped in glass—Bernice slid me a picture I didn’t know how to take.

Penelope sat on a sofa upholstered in a floral so busy it could hide stains and sins. Her hair was loose for once. Her belly—mine once—was round beneath a borrowed dress. Next to her, a boy not much older than her own seventeen or eighteen. He had the kind of beauty that gets boys into trouble and then out again: open face, shy smile, a steadiness you’d miss if you didn’t know to look for it. His hand hovered an inch above her knee like both a promise and a permission request.

On the back, in Clara’s scolding cursive: P. with M. — absolutely not.

“Marcus?” I said it like a test.

Bernice’s nod was a small benediction. “Marcus Lee.”

“Is he—?” The question snagged. My throat had been waiting for it.

“Gone,” she said gently. “Car wreck, winter of ’97. Black ice on Highway 12. He’d moved up to Atlanta to work at a garage. Came down to visit his mama and didn’t make it back.”

I pressed a hand to my chest like I was catching something falling through me. “My mother always said she met David in college,” I said. “Married quick. Then me.”

“Because it was quicker,” Bernice said, not unkind, “than telling the truth.”

She reached for another folder, this one slimmer. A church record book, the leather cracked. Pastors wives keep better books than pastors; everyone knows that. Inside, a page handwritten in neat blue ink:

Edwards, Penelope Marie — confession of faith, 1993 (with child). Referred to aunt, M. Pearson. Left for Atlanta, spring 1994. Returned summer 1997. Married David Quinn in August. Child born October—Vivian Marie.

My birth certificate says October. The marriage license says August. The math, for once, was not metaphor.

Amy had gone quiet beside me. Eli, in her lap, gnawed on her knuckle like it was a teething ring he trusted more than rubber.

“Did David know?” I asked the air, because Bernice could only give me paper.

“Men like David,” Bernice said, fingertips smoothing nothing on the table, “know what they love and what they don’t. He loved your mama’s ambition and the way she fit into a room where deals were made. He didn’t love questions with long answers.”

The courthouse was a square of brick and resignation. The clerk raised eyebrows at my request and then, maybe in defiance of the way the world looks at girls with babies, went to fetch the archived records anyway. We left with copies—a marriage license, notarized, with a date that made my stomach drop and then settle, a hospital record from a prenatal clinic just outside Celler County listing patient: Penelope E. and, handwritten in the margin, father unknown.

Driving back, Eli slept the way babies do when the car tells them a story: steady and repetitive and humming. Amy traced her finger along the marriage license, her nail catching on the raised seal.

“What are you going to do?” she asked.

“Keep writing,” I said. “And tell him everything when he asks.” I glanced in the rearview at the curve of Eli’s cheek. “And decide what to do with the name ‘Quinn.’”

The family blew apart and came together along lines I didn’t predict.

Aunt Jennifer, who had always liked seating charts more than conversations, showed up with lasagnas and offers to drive me to the pediatrician. Uncle Steve sent me the number of a lawyer “in case you want to get some things on paper.” Three cousins I hadn’t seen since I was twelve texted pictures of their grandkids and said, He’s beautiful. We were wrong. Amy’s mother called to apologize and ended up crying for the better part of fifteen minutes, not only for me but for the girl she’d been who chose silence because it seemed like loyalty.

The other side did what the other side always does. Silence. Averted eyes at the grocery store. One email that used the word unseemly in a paragraph so tight with righteous grammar it squeaked.

It turned out relief could be a kind of grief. I missed the simpler stories even as I was glad to have set them on fire. I missed the idea of a mother who would have defended me at the hospital—who would have said my grandson without looking for the nearest mirror. Missing the idea didn’t bring back the woman. It just made the quiet around her absence more honest.

Delilah called to check in and ended up telling me about Leonard’s hands—how he repaired radios by listening before he ever touched a wire. “He could hear where the static was thickest,” she said. “Then he’d start there.” I wrote that down in the journal under a heading I didn’t know I’d been creating: What I Want Eli to Know About the Men He Comes From.

I added Marcus to that list. What I had: a photograph, a name, a winter road. What I imagined: the way he looked at my mother in that picture—like someone whose love had not yet been turned into a liability.

And because I believed in symmetry, I texted David Quinn.

I know, I wrote. I have records. If you ever want to talk about the truth instead of the performance, I will meet you where you are. I won’t pretend for you. I will be kind if you can, too. He read it. Two pulsing dots. Then nothing. It felt less like rejection than like muscle memory—his, not mine.

I didn’t expect Penelope to come back to the house. She doesn’t repeat scenes unless she’s certain of her lines. She texted once, two weeks out:

Please stop sending things to my friends. This is humiliating.

I typed and deleted three replies before I settled on the only one that felt like it belonged to the person I’m trying to become.

Truth humiliates lies. Not people. I won’t send anything else. The truth is traveling on its own now.

She didn’t answer. But three days after Eli turned seven months and learned how to clap for himself, she sent a second message.

I’m in Celler County. I need you to come. Church on Miller Street. Tomorrow, 2 p.m.

I called Delilah. She sighed the sigh of a woman who has played every role in a family drama and is tired of the costume changes. “Go,” she said. “Take your baby. Wear shoes you can stand in for a while.”

The church looked like every Southern church that’s ever taught more than it admitted—white paint, steps that needed repair, a kitchen that could produce a funeral spread on an hour’s notice. The sanctuary was empty except for the soft drone of the air conditioner and a woman at the piano playing chords that didn’t want to be hymns.

Penelope sat three pews from the back. She had aged ten years in two weeks. Not in the way makeup can fix. In the way that happens when a person drops a mask and the face underneath hasn’t known air in decades.

She turned as if she’d heard the thought. Her eyes swept Eli, then me, then the binder under my arm. She flinched at the binder like it was a weapon. Maybe it was.

“Thank you for coming,” she said. Her voice was fine china in a sink.

I didn’t sit. “Why here?”

She gestured, a tiny irritable flick of her wrist. “Clara was married here. So was my aunt. So was—” She closed her eyes. “They keep records.”

“And confessions.”

A flare of the old heat. Then it guttered. “I came to… look.” She glanced toward a wall lined with framed black‑and‑white photographs of people smiling in ways that meant it. “I wanted to see what I—what we—threw away.”

Amy, who had come and was now making faces at Eli that made him kick his feet hard enough to thump the pew, cleared her throat in a way that meant I’m here if you need to step away. I nodded without looking.

“I found Marcus,” I said. “On paper. In a photograph. On a highway.”

Penelope’s mouth compressed. “He wasn’t—” She stopped, and in the space where the lie would have once unfurled, another kind of sentence assembled itself. “He was kind,” she said, like she was at the far end of a tunnel speaking into a can attached to a string. “He would have married me here. He asked. Clara said I would break our necks on that choice.”

“And David?”

She swallowed. “He liked that I could be what he needed. He never asked about dates. I never offered them.” She looked at Eli, then away, the motion abrupt. “I thought I was keeping us safe.”

I let the words sit between us until they stopped performing and started sounding like breath. “Safe from what?”

“The look people give you,” she said, and for the first time in my life I heard the girl inside her speaking straight through her. “The look you learn to anticipate so you can beat it to your own face. The way doors close quietly. The way ‘no’ gets said without lips moving.” She laughed, and the sound cut. “And then I became the person doing the looking.”

There it was. Not apology. Not yet. But a mapping.

“The thing about safety,” I said, “is that if the price is your soul, you’re just renting a nicer cage.”

She winced. “I know,” she said. “Now.”

We sat. Eli reached for the air and grabbed a dust mote. I took a breath that traveled all the way to my feet. “Here’s what’s going to happen,” I said, because for once the plan didn’t feel like a threat but like a path. “I’m changing my name. Not all the way. Eli and I are going to be Davis‑Quinn. We are not deleting the parts of us that don’t fit your mother’s letter.”

Penelope closed her eyes as if I had poured cold water over her head. “All right.”

“You are going to tell your friends—your bridge club, your charity board—that you lied. To them. About me. About yourself.” I didn’t raise my voice. I let the words do the heavy lifting. “If you choose not to, I will not correct the record for you again. Silence is expensive. You can pay for it if you want to. I won’t.”

She flinched, but she nodded—the smallest, truest nod I’ve ever seen her make.

“And,” I said, and here the part of me that is my father’s daughter, my grandfather’s granddaughter, steadied my mouth, “when Eli is old enough to ask you why you tried to make him a mistake, you will tell him about Leonard. And Marcus. And Clara. And the cost of being the kind of woman people reward. And you will ask him what he needs from you then. Not what you need from him.”

Her hands had been folded in her lap this whole time. She opened them as if they ached. “Will you ever forgive me?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said, and the honesty shamed nobody. “I know I will keep Eli safe from the part of you that confuses love with erasure. I know I will build a family around him that tells the truth even when it sits like a stone in the mouth. I know if you want to be in that family, you will have to practice a new language.”

We left it there. Not a reconciliation. An agreement to stop pretending we were at war about the small thing when the real thing was enormous.

Outside, the air was bright and ordinary. Amy loaded Eli into his car seat while I leaned my head against the warm roof and let my bones rest for the first time since the hospital’s humming lights.

“Do you feel better?” she asked.

“I feel… accurate,” I said, and somehow that was better than better.

The weeks turned into a pattern that made sense. I enrolled in classes that would push me toward the degree I’d delayed. I filed the paperwork for our name change and cried in the car after the clerk stamped it because a stamp should not feel like a sacrament, and yet. Aunt Jennifer learned how to fold a stroller in under ten seconds and strutted around the farmer’s market like she was newly elected mayor. Delilah mailed me a recipe card in Clara’s hand for a sweet potato pie that used too much nutmeg, and I decided to make it anyway because history isn’t improved by skipping the parts that make your tongue tingle.

David Quinn emailed two sentences the day the county paper ran a small notice about the name change in a bureaucratic column nobody reads unless they’re getting married or sued.

I did know. I’m sorry. I’m sorry in the way a person is when being sorry doesn’t fix anything. It wasn’t nothing. I printed it and filed it under For Eli — When He Asks About David.

Penelope didn’t come back to the house. She sent a postcard from a coastal town with a picture of a lighthouse trying its best. On the back: I told them. It was not dramatic. It was not gracious. It was true. — P. It wasn’t an apology. It was the only thing she had that resembled one. I put it in the binder because the binder had stopped being a dossier and started being an archive. And archives are just a way of saying, we were here, and this is what we carried, and this is how we put it down.

On Eli’s eight‑month day, we stood in a park with grass like the color green meant it. Amy took a picture of us under a tree—his fist full of my collar, my smile not pinned in place but rising from somewhere actual. I sent the photo to Delilah and Aunt Jennifer and, after another minute of choosing, to Penelope. She replied with a single line that surprised me by not making me angry.

He looks like everyone we come from.

“Yes,” I texted back. Just that.

Before I slept that night, I opened the green journal and wrote across a clean page:

Eli,

Here is what I know now that I didn’t know when you were born under lights that hummed like bees.

You come from a line of people who learned how to be smaller to survive. Some of them got so good at it they mistook the shape they’d made for who they were. Some of them—Leonard with his listening hands, Marcus with his kind eyes, Delilah with her calling things by their names—left the door open for air. We are going to stand in that doorway and let the truth move through us, even when it raises goosebumps. Especially then.

Your skin is not a question. Your name is not an apology. Your joy is not a debate. When people forget that, we will remind them. When we forget, we will forgive ourselves and correct course.

I will tell you the story of how your grandmother packed a suitcase instead of unpacking a lie. I will tell you the story of how she came back, not as a mother exactly, but as a woman trying to learn a new language in a mouth that had only practiced silence. If she keeps learning, we will keep letting her take the next lesson. If she stops, we will not be her chalkboard.

When you are old enough, I will take you to a small church on a street named for a man who probably owned other men once, and we will stand in front of a wall of photographs and you will see faces that look like yours and mine in different ratios. I will say their names out loud so that the room knows what to do with us. You will clap for yourself the way you do now, wildly impressed by the miracle of your own hands. I will not tell you to quiet down.

You were the truth that blew our house open. You were also the reason the light finally got in.

—Mom (Davis‑Quinn)

I tucked the journal back under the onesies like it belonged to both places—what’s written and what’s worn. The house was quiet in the way that means rest, not restraint.

Before I turned off the lamp, I slid the binder one shelf higher. It didn’t need to be within reach anymore. Not because the world had changed its mind about who we are, but because I had. Truth would sit on that shelf like a book we knew by heart. We wouldn’t have to clutch it to our chest every time we walked from one room to another. That’s the thing about telling the truth long enough: eventually, it starts telling you back.

And when I finally slept, I dreamed not of fluorescent lights or garbage cans or buses, but of a little boy clapping for himself under a broad, forgiving sky.

Part 3

The first time Eli called me “Mom Davis-Quinn,” he was two and a half and just wanted a snack.

“Mom Davis-Kwin,” he said from the floor, cheeks sticky with yogurt, “more crackers.”

He’d heard the full name at the DMV, when I’d balanced him on my hip while they took the worst photo of me known to humankind. The woman behind the counter had handed me my new ID with a bored, “Vivian Marie Davis-Quinn?” and Eli, human tape recorder, had pocketed the syllables like treasure.

I looked down at him now, at the way his eyebrow crinkled when he was serious, at the caramel tone of his skin against the cheap apartment carpet, and felt a pulse of something I hadn’t had in a long time: correctness.

“Sure, kid,” I said. “But you can just call me Mom. The government already gave me the long name.”

The apartment we lived in then was small and loud; you could hear the neighbors’ arguments come through the vents like extra channels on a TV. It was also ours. The lease had both our names on it—mine typed, his scribbled in crayon at the bottom because he insisted on signing too. Amy had helped me move. Aunt Jennifer had contributed dishes. Delilah, after one look at the building’s cracked staircase and Eli’s unsteady run, had mailed me a baby gate rated for the apocalypse.

We’d left my mother’s house a year after she walked out.

It wasn’t a dramatic eviction. There were no cops or slammed doors. There was just a slow realization that every time I stepped into a room, I was checking it for ghosts that hadn’t earned that kind of rent-free living. The tasteful hydrangeas, the echoing kitchen, the dented trash can—I could feel them watching me relearn how to breathe.

“You can stay,” Aunt Jennifer said when I announced we were leaving. “That’s your home too.”

“It’s a museum,” I said. “I need a place where I’m allowed to spill.”

The day we left, the house didn’t protest. No pictures fell off the wall in solidarity. The only sound was Eli’s delighted shriek when he realized boxes were apparently the world’s best hiding spots.

My name change had gone through three months before that, after a parade of forms and fees and one judge who double-checked and then triple-checked that I knew what I was asking.

“Most people are trying to get rid of names,” he’d said, peering over his glasses. “You’re adding one.”

“I’m not losing anything,” I told him. “Just… rebalancing.”

He’d stamped the form with a thud that felt like a gavel in a movie, and suddenly the paper world acknowledged what my bones already knew: I was not just a Quinn with the past air-brushed out. I was Davis-Quinn, carrying both halves whether anyone liked the symmetry or not.

Eli’s birth certificate took longer. Bureaucracy always does when it comes to children. But one afternoon, a new document arrived in the mail, his name rewritten with the hyphen, my name corrected in the “mother” field. I held it under the kitchen light and felt the tiniest click inside me, like a lock catching properly.

“Look, buddy,” I said, waving it at him. He was coloring on the floor, making all the trees purple.

He looked up. “Paper,” he said.

“Yes, but like, important paper,” I said.

He blinked. “Can I color on it?”

“Absolutely not.”

He shrugged and went back to his trees. It was the right response. I wanted his relationship to these documents to be casual, bordering on bored. I’d done the panic. He could do the living.

Spring came early that year, some bureaucratic confusion in the weather system. Amy stood in my doorway holding a garment bag like it contained contraband.

“Pack the diaper bag,” she said. “We’re going on a field trip.”

“To where?” I asked, already reaching for wipes and snacks.

“Church on Miller Street,” she said. “Bernice called. There’s a Davis family picnic. You’ve successfully outed everyone. Now you get potato salad.”

Celler County looked different in sunlight with Eli babbling to his stuffed elephant in the back seat. Less like a time capsule, more like a place that had kept going even when nobody wrote it into the family script.

The picnic was behind the church, under a stand of live oaks whose branches had seen more secrets than a confessional. Folding tables groaned under the weight of food: fried chicken, mac and cheese, three varieties of greens, deviled eggs arranged like a defensive line. Kids ran in loops, leaving streaks of dirt and laughter.

Bernice spotted us from across the yard and lifted her hand in a small wave. Her face creased into a smile that reached all the way up.

“There she is,” she said, pulling me into a hug that smelled like cornbread and hair oil. “And there he is.”

Eli, who had never met a stranger he couldn’t charm, reached for her earrings immediately. She laughed and took him, settling him on her hip like she’d done it a thousand times.

“You brought him,” she said to me, as if that was an act of grace.

“Of course I did,” I said. “He’s the one with the good genes.”

She snorted. “Don’t let the boy know that too early. He’ll be impossible.”

Delilah was there too, along with three other cousins I’d never met and two I vaguely remembered from childhood Christmases. There were photos of Leonard propped against a centerpiece like he was an honored guest: younger, older, in uniform, out of it. People went up and touched the frames the way Catholics make the sign of the cross.

“You have his eyes,” one aunt said, studying me like a puzzle piece that finally slipped into place. “Not just how they look. How they look at people. Like you’re listening even when you’re tired.”

“I am tired,” I said. “So that tracks.”

They wanted stories from me, which felt backwards at first. I was the one who’d come hungry for history. But as the afternoon unfolded, I understood. I was the bridge now—between the branch of the family that had been cut off and the one that had kept hanging on.

They listened as I told them about the hospital room lights, about my mother’s first words, about the six DNA tests and the binder and the attic. They winced and clucked and swore quietly in ways that would have made church ladies flinch.

“That woman always did love a performance,” Bernice said, shaking her head. “I just never thought she’d forget it was an act.”

“She’s trying to remember,” I said, surprising myself with the gentleness in it.

“You don’t see it?” Delilah asked. “You did that. You and that baby. Y’all turned the stage lights on.”

I watched Eli chase a bubble one of the older kids had blown. He toddled after it, arms out, face rapt. The bubble burst against his nose and he blinked, momentarily stunned, then laughed like the world had told him a joke.

I had turned on a light, yes. The shadows hadn’t vanished. But at least now we could see what we were tripping over.

We visited Leonard’s grave at dusk.

It was small, simple, the grass trimmed neatly around it. Someone had tucked a plastic flower into the ground near his name. I made a note to bring real ones next time.

Eli squatted beside the stone and patted it like a dog. “Hi,” he said, because that’s what he says to everything: lamp, tree, shoe.

“Hey, Granddad,” I said, feeling ridiculous and then not. “You don’t know me, but I’ve been busy cleaning up some of your daughter’s mess.”

The wind rustled the leaves overhead, the cheap kind of metaphor movies love. I took it.

“I’m trying to do better with your great-grandson,” I went on. “Trying not to teach him how to disappear.”

Delilah stood a few paces back, giving us space like a curtain call audience. “He loved a stubborn woman,” she said softly. “Clara, Penelope, his sisters. Drove him crazy. Made him proud.”

“I’m honored to continue the tradition,” I said.

On the drive home, Eli finally fell asleep, mouth open, cheeks flushed with sun and sugar. Amy dozed in the passenger seat with her sunglasses crooked on her head. The highway slid under us like a moving walkway in some airport between lives.

I thought of my mother somewhere on that same axis—driving back and forth between the name she chose and the one she’d been given, between the truth and the story she’d sold. I didn’t know where she’d land. For the first time, I also knew it wasn’t solely my job to make sure she landed upright.

At home, I tucked Eli into bed and stood in the doorway watching him breathe. The apartment was quiet in a way that felt earned. My binder sat on the bookshelf, now wedged between a cookbook and a sociology textbook, the spine labeled in my neatest handwriting: FAMILY: FACTS.

The green journal lived on the nightstand.

I pulled it out and wrote:

Today, you ate three deviled eggs and half a drumstick and met a dozen people who claim you proudly. You said “bubbles” for the first time, except it came out “buh-bohs,” which I think is better. You stood on your great-grandfather’s name and didn’t know you were standing on a line someone tried to erase. I cried in a bathroom that smelled like a hundred potlucks and nobody asked me to stop.

You are not saving us, Eli. That’s not your job. But you did walk in like a siren and made it impossible for us to keep sleeping through the fire alarm.

Love,

Mom

Part 4

The first time someone assumed I was Eli’s nanny, he was four and I was too tired to be polite.

We were at the park near our apartment, the one with the creaky swings and the slide that smelled faintly of last summer’s sunscreen. Eli was on the monkey bars, hanging upside down like gravity was an optional suggestion.

A woman in athleisure approached, pushing a stroller that cost more than my first car. She had the kind of casual tan that comes from vacations, not genetics. She stopped near me, eyes on Eli.

“He’s adorable,” she said. “Where do you nanny out of?”

I blinked. “Excuse me?”

“The family you work for,” she clarified. “Do they live in the complex? We’re looking for someone. You seem great with him.”

I felt my jaw tighten. I did a quick mental inventory: my hair pulled back, yesterday’s jeans, a faded T-shirt with my community college’s logo. Eli, brown and bright. Me, brown and bright. It wasn’t the first time strangers had misfiled us. It had never stopped stinging.

“I work for Eli’s mom,” I said, letting the words slide out.

“Perfect,” she said. “Is she taking on any new families?”

“I have no idea,” I said. “You’d have to ask her. She’s at the grocery store. I’m filling in.” I raised my voice. “Hey, Eli!”

He flipped clumsily and dropped to the ground. “Yeah, Mom?” he called.

The woman’s eyes widened. “Oh,” she said. “I just—he doesn’t…”

“Look like a cliché?” I said. “I know. Wild.”

Color crept up her neck. “I didn’t mean—”

“I’m sure you didn’t,” I said. “But he hears what’s implied, even if you don’t say it. So maybe next time, lead with ‘He’s adorable’ and leave it there.”

Eli trotted over, oblivious to the adult weather. “Can I get ice cream at home?” he asked.

“You’ve already had half the playground,” I said. “Your odds are excellent.”

The woman muttered something that might have been an apology and rolled her stroller away, her leggings whispering against each other like dry leaves.

On the way home, Eli swung our joined hands. “Why was that lady’s face pink?” he asked.

“She realized she said something silly,” I said.

“Like when I call a dog a cat?” he asked.

“Kind of,” I said. “Except dogs don’t feel hurt when you do that. People do.”

He thought about it, his brow furrowing. “Did she hurt you?”

“A little,” I said, because I’d decided we weren’t doing the We’re Fine That Didn’t Hurt School of Emotional Denial. “But I can handle it. My job is to make sure people don’t hurt you on purpose. Or get away with it when they do.”

He nodded, satisfied, and launched into a story about a dragon who was allergic to fire.

The real test came a year later.

Kindergarten Family Day arrived like a pop quiz I hadn’t studied for.

The flyer in Eli’s backpack was cheerful to the point of aggression: FAMILY TREES! ALL FAMILIES WELCOME! COME SHARE YOUR ROOTS! The instructions were clear: “Help your child make a family tree poster. Bring photos or drawings. Be ready to talk about your relatives!”

I looked at the calendar and then at the bookshelf where the binder waited. The idea of handing my five-year-old a visual aid containing passing, paternity fraud, and three generations of shame seemed… excessive.

I brought it up with his teacher, Ms. Harper, at pickup.

“Some families have… complicated trees,” I said, doing my best to sound casual. “Like, more forest than diagram.”

She nodded, her silver curls bobbing. “We try to keep it broad,” she said. “The point is to help the kids understand they come from somewhere. However you define family is fine. Pets count. Friends count. If a relative is a sore subject, skip them. This isn’t therapy. It’s glue sticks.”

I laughed. “Okay. I can do glue sticks.”

At home, I pulled out a poster board and sat cross-legged with Eli at the coffee table.

“Who do you want on your tree?” I asked.

He frowned in concentration. “You. Me. Auntie Amy. Aunt Jennifer. Aunt Deli—Delaila. Uncle Steve. That funny guy with the hat—”

“Cousin Reggie,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said. “And… Grandma Pen.”

The marker paused in my hand.

He’d met my mother exactly twice since the church on Miller Street. Once, she’d stopped by the apartment unannounced with a bag of high-end baby clothes Eli outgrew in a month. The second time was at his third birthday party, where she’d perched on a folding chair like it was a witness stand and watched other people hug him. She’d brought a quiet gift—a small wooden train set with his full name carved into the cars. The first time she’d ever written “Davis” without flinching.

“Do you want Grandma Pen on your tree?” I asked carefully. “Or are you putting her there because you think you’re supposed to?”

He thought about it for so long I almost prompted him again. Then: “She’s your mom,” he said. “So she should be… somewhere.” He squinted. “But maybe not near the trunk. Maybe in the branches.”

I did my best not to cry over the level of metaphor coming out of a five-year-old.

“Branches it is,” I said.

We spent the evening drawing circles and lines. Instead of names like “Mom” and “Dad,” we used roles he understood: Mom, Grandmas (Pen, Clara-Bernice in one circle because explaining Clara-versus-Bernice felt more grad-level), Granddad Leonard, Grandpa David (in parentheses, per my lawyer’s suggestion), Aunties, Cousins, Uncle Who Makes Loud Jokes.

For the roots, he wanted “God,” “trees,” and “pancakes.” I did not argue. In a family like ours, pancakes had done as much to hold people together as doctrine.

Two days before Family Day, my mother texted.

Eli asked if I could come, she wrote. I would like to. If you’ll allow it.

He’d mentioned it in passing over FaceTime, the way kids do when they unintentionally drop a grenade.

“Grandma, you should come see my tree,” he’d said, legs swinging off the couch. “I put you on a branch.”

Penelope had blinked rapidly and smiled too hard. “Is that so?” she’d said. “We’ll see, sweetheart.”

Now, the question sat in my messages like a test.

Amy rolled her eyes when I showed her. “She doesn’t deserve him,” she said.

“Maybe,” I said. “But he invited her. This is his story too now.”

“You’re really going to let her in that classroom?”

“I’m going to let her stand in the back and watch him claim people,” I said. “If she makes it about herself again, I’ll escort her out.”

“Like security at a concert,” Amy said, grinning. “I volunteer as backup.”

Family Day smelled like Elmer’s glue, anxiety, and juice boxes.

The classroom walls were a riot of construction paper and crayon. Tiny desks had been pushed into a horseshoe. On the back wall, the family trees were taped in filing-cabinet rows.

I saw ours before I saw her.

Eli had insisted on drawing everyone himself, so the poster looked like a hallucinogenic forest. My circle had curly hair that took up half the page. Leonard’s was just a beard and a smile. Penelope’s was a triangle dress and a straight line for a mouth.

“Accurate,” Amy murmured.

Parents milled about, murmuring. I recognized a few from the drop-off line. The athleisure nanny-job woman was there, which was the universe showing off its sense of humor.

Penelope stood near the doorway, in a navy dress that might have been black in other lighting. For the first time ever, she looked… underdressed. Her hair was looser than I’d ever seen it, strands escaping like a truth trying to get free. She clutched her purse like a flotation device.

“Hi,” I said. It came out less sharp than I’d expected.

“Hello,” she said. Her eyes flicked over my outfit—nice sweater, jeans without holes, sneakers—and didn’t flinch. Progress.

Eli barreled into her shins. “Grandma!” he yelled. “You came!”

Her knees nearly gave. She caught herself on a table, then crouched, putting herself on eye level with him.

“I did,” she said. Her voice wobbled. “I came to see your tree.”

He grabbed her hand and tugged her toward the wall. “Look,” he said, pointing. “You’re right here. On this branch. Not too high. Not too low.”

She stared at the lopsided circle with “Gma Pen” scrawled inside in red marker. For a second, I thought she might cry. Then she did something rarer: she laughed.

“Perfect,” she said. “That’s exactly where I should be.”

Ms. Harper clapped her hands for attention. “Okay, families!” she said. “We’re going to go around and let the kids tell us who’s on their tree.”

One by one, tiny humans stood up and narrated their posters.

“This is my mom and my other mom and my cat,” one girl said proudly.

“This is my dad and my grandma and my grandpa who lives in heaven,” a boy said. His father’s hand tightened on his shoulder.

When it was Eli’s turn, he bounced to the front of the room like the concept of anxiety had never been explained to him.

“This is my family,” he said, sweeping his arm like Vanna White. “This is my mom. She works and goes to school and makes pancakes and sometimes says bad words at the TV.”

Laughter rippled. I covered my face.

“This is my Auntie Amy and Aunt Jennifer and Aunt Deli—Dela—Lilah,” he continued, stabbing each circle. “They help with me. This is Grandpa Leonard. He’s dead but he’s still mine. This is Grandpa David. He’s alive but he doesn’t come over. This is Grandma Pen. She’s learning to talk different. This is my cousins and my friends and our neighbor Mr. Dan who lets me pet his dog.”

The room was quiet in a way I hadn’t expected. No nervous chuckles, no throat clears. Just listening.

“This is my roots,” Eli said, patting the bottom of the poster. “God and trees and pancakes.”

Ms. Harper blinked rapidly. “Thank you, Eli,” she said. “That was… thorough.”

As the other parents clapped, a woman near the back—athleisure mom—raised her hand.

“Ms. Harper?” she said. “Can I ask a question?”

Oh, good, I thought. Here we go.

“How did you get them to talk about their families like that?” she asked, her voice genuinely curious. “My parents never told me anything. We just had this… vague tree, and a lot of silence.”

Ms. Harper smiled. “You ask open questions,” she said. “And you don’t flinch at the answers. Kids can handle the truth better than we think. It’s usually the grown-ups who need to catch up.”

I felt Penelope shift beside me. She was standing closer than I’d realized, close enough that our sleeves brushed.

After the official part ended, we mingled. I braced for comments, but most were simple.

“I liked his roots,” one father said. “We might add pancakes to ours.”

“Your boy’s got a good sense of humor,” another mom said. “And vocabulary. ‘Learning to talk different’—I might steal that.”

At the snack table, someone knocked over a juice box. The red puddle spread toward a stack of napkins.

A little boy standing nearby pointed at Eli and said, matter-of-factly, “He’s brown like my dad.”

“Yes,” his mother said. “And you’re brown like your dad. And I’m pink like a shrimp. We’re all a little different. Cool, huh?”

“Yeah,” the boy said, and reached for a cookie.

No drama. No self-consciousness. Just a normalization so smooth it made my chest ache.

When things finally thinned out, Penelope and I found ourselves alone near the window, watching Eli and Ms. Harper clean up glue caps.

“You let him put David on there,” she said quietly.

“He’s part of the story,” I said. “Even if he doesn’t act like it.”

She nodded. “And me.”

“And you,” I said. “Exactly where he placed you.”

She exhaled. “When he said I’m learning to talk different…” She trailed off.

“You are,” I said. “He noticed. That’s his way of saying he’s watching.”

“I don’t deserve his grace,” she murmured.

“Probably not,” I said. “But he’s five. He’s giving it anyway. Your job is not to squeeze it until it turns into something else.”

She smiled, faint and painful. “You don’t pull punches, do you?”

“Not with people who can take them,” I said.

She reached into her bag and pulled out a small envelope.

“I brought something,” she said. “From Celler County. For your binder.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Our binder, now?”

She huffed a laugh. “Don’t push it.”

Inside the envelope was a photocopy of an old church bulletin. On the back, in Clara’s handwriting, a recipe for the sweet potato pie I’d already massacred once. Beneath that, in younger, wobblier script—Penelope’s—my mother had written at seventeen: I will be brave. Then someone—Clara?—had crossed out brave and written smart.

“I found it in the records room,” Penelope said. “I remembered you telling me about the pie. And I thought… maybe you deserved the first version, not the edited one.”

I stared at the words. Brave underlined, the ink pressed deep.

“Thank you,” I said. It was not absolution. It was accurate.

That night, after Eli went to bed smelling like washable paint and ham, I slid the bulletin into the binder. Then I pulled out the journal and wrote:

Today, you told a room full of people that your grandma is learning to talk different. You mercifully did not mention my TV vocabulary. You put dead and distant family on the same level. You rooted yourself in carbohydrates. Your grandmother brought you a piece of her past with the wrong word scratched out and the right one underneath. I think that qualifies as extra credit.

Love,

Mom

Part 5

When Eli turned sixteen, he took my car keys and my breath away in the same month.

He grew fast, all at once, the way boys do when their bones decide they’re tired of being modest. One minute he was my monkey-bar kid; the next he was standing at the fridge, the top of his head level with the freezer, asking if we had more milk in a voice that had dropped an octave overnight.

“You’re enormous,” I said, squinting at him like the right angle would make him shrink back down.

“Thanks?” he said.

He passed his driver’s test on the first try. When the DMV employee handed him his license, she grinned. “Freedom,” she said.

He rolled his eyes. “For me, maybe,” he said. “My mom just got a lifetime subscription to anxiety.”

She looked at me. I shrugged. “He’s not wrong.”

That summer, the house was different.

We’d moved again when Eli was ten, into a small bungalow with peeling paint and a yard that needed more love than I had time for. It had three bedrooms and a porch swing and floors that groaned like an old man in need of coffee. It had cracks and quirks and a mortgage in my name. It was the opposite of my mother’s museum, and I adored it.

The binder lived on a higher shelf now, shifted over to make room for Eli’s stack of graphic novels and the SAT prep book he pretended not to read. The green journal had been filled and replaced twice; its successors were blue and red, an accidental flag of feelings.

Penelope came by on Sundays.

Not every Sunday—that would have been too predictable for her. But often enough that the path from her car to our porch had worn a conceptual groove. She’d sit with Eli on the swing, and they’d talk about school, music, the podcast he liked where people told stories about history without falling asleep. Sometimes she’d bring clippings from newspapers about civil rights cases; sometimes she’d bring nothing but herself.

She had remarried, briefly, to a man from her church who liked his shirts starched and his worldview simple. That ended when he suggested Eli call him “Granddad.” She’d told him, in the living room, with Eli in the next room and me in the kitchen pretending not to listen, that titles were earned. He’d left with his shoes in his hand, which felt metaphorically correct.

“You are not allowed to tell him I defended you,” she said afterward, pouring herself tea with shaking hands.

“I am absolutely allowed,” I said. “I might make a scrapbook.”

“She’ll explode,” she muttered.

She didn’t. That’s the thing about people who think they’ll shatter if they change; sometimes they bend instead.

One evening in July, when the cicadas were doing their overwrought orchestra thing and Eli was out with friends pretending they weren’t all terrified of merging onto the highway for the first time, I heard a noise from his room that wasn’t usual.

He’d left his door half-open. The lamp was on. I knocked gently on the frame.

“You good?” I asked, expecting to find him on his laptop or asleep at a weird angle.

Instead, I found him sitting cross-legged on the floor, the green journal—the original one—open in his lap. The binder lay next to him, splayed like a sunburst of documents.

My heart did a complicated move in my chest.

“How long have you known about those?” I asked.

“Since I could reach that shelf,” he said, not looking up. “You’re tall. Your shelves are short.”

“Fair,” I said, stepping in. “Do you want privacy, or do you want company?”

He considered. “Company,” he said. “I think.”

I sat down across from him, crossing my legs the way you do when you really commit to a conversation.

He tapped the journal. “You write like a therapist,” he said.

“I write like someone who couldn’t afford one,” I said.

He huffed a laugh. “You wrote about everything,” he said. “The hospital. Grandma. The DNA tests. The bus picture. Celler County. Marcus. Leonard. David.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I didn’t want you finding out from someone who weaponized it. Or from a half-assed family legend.”

He flipped carefully to a page he’d dog-eared.

“You wrote this when I was eight months,” he said. “About taking me to the church and not telling me to be quiet.”

“I remember,” I said. “You drooled on the hymnals.”

“I still do,” he said.

We sat there for a minute, the bugs outside doing their best impression of static.

“How do you feel?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Weirdly… not shocked?” he said. “Like, I always knew there were gaps. I just didn’t know what shape they were.”

“That tracks,” I said. “Kids always know when adults are skipping pages. They just don’t know which ones.”

He traced the edge of a DNA report with his finger. “Grandpa Leonard,” he said. “He never got to meet you.”

“No,” I said. “But he shows up anyway. In stories. In your face when you’re concentrating. In the way you listened to that kid in your class when his parents were divorcing and everyone else changed the subject.”

“Stalker,” he said.

“I pay attention,” I said. “It’s my job.”

He shifted his focus to another stack. “Marcus,” he said. “Do you think he’s…?”

“My biological father?” I finished for him. “Probably. The paperwork points in that direction.”

“Have you ever wanted to… I don’t know. Find his grave? Talk to his mom?”

“I talked to Bernice,” I said. “And some others. His mom passed a few years back. I’ve visited his grave. Once with you, when you were little. You tried to eat an acorn.”

“I still might,” he said. Then, more serious: “David knew?”

“He knew enough,” I said. “He chose not to look too closely. That’s its own kind of answer.”

“How angry are you?” he asked. “At him. At Grandma.”

Somewhere in the next room, the fridge kicked on, a low mechanical hum.

“It depends on the day,” I said honestly. “Part of me is furious. Part of me is tired. Part of me is grateful they at least gave me you, even if the delivery system was messy as hell. That part feels like a traitor sometimes.”

He nodded, chewing on his lip. “I’m mad,” he said. “On your behalf. And kind of on mine, even though I wasn’t… there yet.”

“Valid,” I said.

“I also…” He sighed, exasperated with himself. “I also feel bad for Grandma. Which is annoying.”

“Welcome to the complicated club,” I said. “We have T-shirts. They all say ‘It’s Not That Simple.’”

“You raised me around her anyway,” he said. “After everything.”

“I raised you around the parts of her that were willing to learn,” I said. “I kept you away from the parts that weren’t. At least, I tried to.”

He nodded slowly.

“Do you regret that?” he asked.

I thought about Sunday porch swings, about the way Penelope’s hand shook the first time she told him, in halting language, that she had been wrong to say what she’d said in the hospital.

“I don’t,” I said. “Because if I had cut her out completely, you’d have grown up wondering what you were missing. This way, you’ve seen her try. You’ve also seen her fail. That’s more data. You get to decide where she lands in your tree.”

He smiled faintly. “Still a branch,” he said. “Not the trunk. Maybe a strong branch now. Maybe with a birdhouse.”

“I’ll allow it,” I said.

He picked up one of the DNA test printouts and squinted at the percentages.

“So, I’m…” He rattled off the ancestries: West African, Ethiopian, Irish, English, “and like four percent Scandinavian, which explains nothing because I hate the cold.”

“That’s the anxiety,” I said. “It’s not ethnic. It’s modern.”

He smirked. “I have… a lot of people,” he said. “In me.”

“You do,” I said. “And around you. Don’t forget around you.”

He glanced up. “Would you be mad if I wanted to… organize some kind of… I don’t know… reunion? Bring all the parts together. Quinns. Davises. Lees. Anyone who’s willing to be in the same room with potato salad and not weaponize it.”

My heart did that dangerous falling thing again, the one from the hospital, the free-fall that means trust.

“I would not be mad,” I said. “I would be incredibly nosy. And I would volunteer to make name tags.”

He grinned. “You can be in charge of the binder presentation.”

“Oh no,” I said. “This is your show. I’ll bring it. You hold it.”

We set a date for the end of August, when people could still claim summer but weren’t quite ready to surrender to school. We rented the park shelter a few blocks from the house, the one big enough to hold thirty people and their grudges.

Inviting people turned out to be the bravest part.

We started with the easy ones. Bernice and Delilah said yes so fast it felt like they’d been waiting for this exact invitation for decades. Aunt Jennifer texted THREE HEART EMOJIS and asked if she could bring her famous ambrosia salad, which everyone hated and everyone expected. Uncle Steve said he’d man the grill if nobody minded the steaks a little too well done.

Amy’s mother, who had once told my pregnant belly at nineteen that she’d “pray I learned my lesson,” replied with: I have a lot to atone for. I’ll bring deviled eggs.

We sent an invitation to David Quinn.

Eli wrote that one.

Dear David (Grandpa?),

We’ve never really talked. I know who you are and I know some things are messy. I’m having a family picnic. All branches are invited. You don’t have to come. But you can.

If you do, I’d like to know what you love. Like, about life. Not about yourself.

You don’t have to answer any tough questions that day. You just have to show up.

From,

Eli (Davis-Quinn)

He sent it as an email and dropped a hard copy in the mail, because he said paper felt harder to ignore.

We also—because the point was the whole tree—included Penelope on the planning thread.

She responded with logistics first: I can bring ice. And plates. And a donation to cover the shelter fee. Then, an hour later: I’ll also bring my humility, which is newer and might get in the way.

The day of the picnic, the sky cooperated.

The air was hot but not hostile. The park grass was patchy in places, lush in others, like a metaphor for us I decided not to overuse. The shelter filled slowly.

Leonard’s side arrived first, a wave of cousins and uncles and aunties and kids whose names I had to write down twice before they stuck. The Quinn side filtered in more tentatively, like they’d RSVP’d to the wrong party and were waiting for someone to tell them so. They wore their Sunday casual—pressed polos, capri pants—with the hesitancy of people not sure if comfort was allowed.

Penelope showed up five minutes early, which for her was the clearest sign of commitment I could imagine. She wore linen pants and a loose shirt, her hair in braids for the first time since I’d been a child. She held a bag of ice and a container of store-bought cookies.

“I didn’t bake,” she said. “I didn’t think this was the day for experiments.”

“You’re here,” I said. “That’s enough.”

She nodded, eyes scanning the shelter. When she spotted Bernice, an entire missile of history, she flinched and straightened simultaneously.

Bernice made the first move. She walked over, arms open, and pulled Penelope into a hug so firm and brief it didn’t pretend to erase anything. When she pulled back, she touched her cheek.

“Look at you,” she said. “Still trying to be a statue. Loosen up, child. You’re among witnesses, not judges.”

“I don’t know how,” Penelope murmured.

“You learn,” Bernice said. “Like a language.”

Penelope laughed, ragged. “That phrase is haunting me,” she said, glancing at me.

“It’s your syllabus,” I said.

David came.

I almost didn’t recognize him at first. Years had softened his jaw and thickened his waist. His hair had gone salt-and-pepper in a way that would read as distinguished if you didn’t know the history tucked between those strands.

He stood at the edge of the group, hands shoved in his pockets, looking like a man who’d arrived at a movie halfway through and wasn’t sure if he should stay.

Eli spotted him before I did. He walked over slowly, calmly, like he’d practiced this in his head.

“Hi,” he said. “You must be David.”

David cleared his throat. “I am,” he said. “You must be Eli.”

“I am,” Eli said. “We agree on something already.”

David laughed, startled. “You look like your mom,” he said. “And like… some people I’ve never had the courage to meet.”

“You’re meeting them now,” Eli said. “There’s potato salad. That usually helps.”

They stood there for a moment, the hardened points of three decades floating between them.

“I’m sorry,” David said finally, voice so low I barely heard it. “To both of you. I took the coward’s way out. I let your mom carry things I should have at least helped hold.”

Eli nodded. “Thank you,” he said. “That doesn’t fix it. But it’s a better beginning than pretending.”

“Can I—” David swallowed. “Can I watch from the sidelines? Today. And maybe, if I don’t screw it up, move a little closer next time?”

“That’s up to Mom,” Eli said, turning to me.

I sighed. “You always put me on the policy committee,” I said.

“You’re good at rules,” he said. “The kind that aren’t cages.”

I looked at David. At his hands, twitching slightly at his sides. At the way his shoulders were squared not in defense but in decision.

“You can be here today,” I said. “You can bring dessert next time. Beyond that is… contingent.”

“Contingent?” Eli repeated. “You really are pre-law.”

“I watch a lot of TV,” I said.

The afternoon unfolded in a series of small, miraculous normalities.

Kids played tag between picnic tables. Someone started a spades game and the trash talk got loud. Leonard’s cousin Reggie told an embarrassing story about me chasing a neighbor boy with a stick when I was six, which Eli found hilarious and I found slanderous. Aunt Jennifer’s ambrosia salad sat untouched until Penelope took a scoop in solidarity and grimaced her way through it.

At one point, a little girl with Penelope’s eyes and Leonard’s nose tugged on Eli’s sleeve.

“Are we really cousins?” she asked.

Eli looked around at the cluster of faces—light, dark, freckled, lined—and then at his own hands.

“Yeah,” he said. “All of us. It’s confusing and cool.”

“Cool,” she said, accepting it immediately the way kids do. “You wanna race?”

“Always,” he said, and they took off.

As the sun started to slip, I gathered everyone for a photo.

“Okay,” I said, clapping my hands. “Tall people in back, kids up front, complicated feelings wherever you can fit them.”

People laughed and shuffled into place. Bernice stood near the center, anchoring. Penelope hovered at the edge until Eli grabbed her hand and pulled her in. David stood two people away from me, which felt appropriately proportional. Amy and Aunt Jennifer flanked me like parentheses.

When we’d all squeezed into the frame, I handed my phone to Ms. Harper, who had shown up because apparently the universe liked full-circle moments.

“On three,” she said. “One, two, three—”

We didn’t say cheese.

We said, at Eli’s insistence, “Truth!”

The shutter clicked.

Later, when the tables were cleared and the grill was cold and people had dispersed, leaving behind only a few stray napkins and the echo of laughter, I sat on the park bench with Penelope.

She watched Eli throw a football with a cousin, his body loose and confident in a way that made me both proud and terrified.

“You did this,” she said quietly.

“We did this,” I corrected. “All of us who stopped pretending the old story was working.”

She nodded. “I was so afraid the truth would take everything from me,” she said. “Status. Friends. The story I told myself about who I was.”

“Did it?” I asked.

“It took some,” she said. “The ones that needed to be taken. The rest…” She gestured at the park. “The rest feels… lighter.”

“That’s how you know it’s working,” I said. “When breathing gets easier.”

She smiled, just a little. “Do you forgive me?” she asked again, softer than the first time, less like a demand and more like a genuine request.

I thought about hospital lights and garbage cans. About attic dust and bus tickets. About an envelope that made her pack a suitcase, and another at a kindergarten picnic that she’d opened with her own hands. About Sunday porch swings and Family Day and the way she’d taken a scoop of ambrosia salad to keep someone from feeling alone in their culinary crime.

“I don’t know that forgiveness is a one-and-done thing,” I said. “I think it’s… cumulative. Today adds points. Some days subtract them. Overall? We’re in the black.”

She exhaled a laugh. “Trust you to turn it into an accounting metaphor.”

“I passed stats on the second try,” I said. “I’m using it.”

She reached over and squeezed my hand, once, briefly. It wasn’t the gesture of a woman who thought she owned me. It was the gesture of someone grateful to be allowed a seat on the bench.

That night, after the last dish was washed and Eli had collapsed on the couch halfway through a movie, I pulled up the photo on my phone.

We filled the frame.