Part 1 of 2

The fluorescent lights of the hospital room hummed, casting a thin, antiseptic glow over everything. I was nineteen and hollowed out by thirty hours of labor, when the nurse tucked a warm, squirming bundle against my chest. He was perfect—ten tiny fingers, ten tiny toes, a full head of dark hair and skin the color of warm caramel. My heart did that dangerous thing they warn you about in parenting books, the free‑fall inside your ribcage that feels like joy and terror and oxygen deprivation all at once.

“Hi,” I whispered, because anything louder would have shaken me apart. “Hi, Eli.”

The door opened with a practiced knock that didn’t wait for permission. My mother, Penelope, stepped in, forty‑seven and immaculate even in a hospital corridor. Her blonde hair was slicked into a severe bun; her lipstick sat precisely within the borders of her mouth. She crossed to the bassinet, eyes skimming over Eli, then me, then back to him.

“He’s quite dark, isn’t he?” she said—polite voice, knife edge.

I pulled the thin blanket higher around him. “He’s got my hair, Mom. And Archer’s nose.”

“Archer is white,” she said, still not looking at me. “Our family is white.”

The words should have bounced off sense—my father was Black, I am biracial, the math isn’t calculus—but I was split open and sleep‑starved and her voice has always found the soft places to press.

“He can’t be yours. Not with skin like that.”

The air left the room like someone had opened a window to space. I tucked Eli closer and my arms shook. The nurse made a careful retreat, closing the door so gently it didn’t latch.

“Mom,” I said, and it came out a rasp. “What are you saying?”

“You know exactly what I’m saying, Vivian.” Blue eyes sharp as copier glass. “You were careless. And now you’re lying.”

For a second I thought I might drop my son. I wanted to scream that genetics aren’t loyalty tests, that her own grandchild was proof of a history she pretends not to have. But all I did was hold him tighter, shield him with my body from a gaze that felt like a winter draft.

Home was worse.

Her house—the one she insists is ours—has always been curated within an inch of its life: white hydrangeas in glass cylinders, coffee table art books no one opens, a bowl of green apples that seem never to ripen or rot. That first week back, Eli’s cries threaded through the rooms and Penelope’s silences grew a second skin. Every floorboard creak felt loaded. Every closed door settled like a judgement.

She didn’t fight me. She never does directly. She called cousins on the house phone and practiced pity like a monologue loud enough for me to hear in the nursery. “It’s just been so difficult,” she sighed into the receiver. “Vivian’s confused. Poor thing. She doesn’t know who the father is.”

The group chats I used to live inside blinked themselves dim. Invitations evaporated. The messages that did come were weaponized sympathy: We’re praying for you. Sometimes these things happen. God has a plan. My son had colic, my stitches burned, and shame—hers, not mine—swept through our family like a rumor with perfect timing.

Archer lasted three visits. Then there was a family emergency, then a double shift, then silence. His name stopped lighting up my phone. Eli cooed at the ceiling fan while I learned how to fall asleep in ten‑minute shards.

I am not sure when the exhaustion hardened into resolve. Maybe it was the day I passed the nursery and heard my mother’s whisper outside his door—“This… this is shame”—the words hitting the paint like mildew. Maybe it was one of the nights when Eli wouldn’t let my body go, and I watched the sky lighten thread by thread and realized no one was coming to rescue us but me.

I ordered a DNA kit at three in the morning with the kind of steady hands I wish I’d had when I was eighteen.

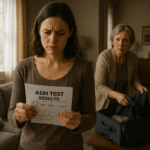

The first envelope arrived two weeks later. I swabbed my cheek, then Eli’s, carefully—no milk on the swab, no stray fibers. I filled in forms, tapped out our names as if the act itself could anchor us to truth. When the results came, the envelope was thick, officious. I was ready to take it to her and say, Read. See. Stop.

She came down the stairs while I was still skimming the summary. I slid the packet beneath a stack of magazines. She picked them up, at random, with the same careless precision she applies to everything that isn’t a mirror.

The branded envelope slipped, white against white. She clocked the logo, the return address, me.

She didn’t open it.

She crushed it in one manicured hand, walked to the stainless‑steel trash can, and let it fall. The hollow clatter at the bottom of the bin was weirdly loud.

“Those things are silly,” she said, brushing her palms together as if she’d dusted a shelf. “Anyone can buy them online.”

It wasn’t dismissal. It was contempt—for evidence, for me, for a grandson she refused to see. That sound in the trash can was a door locking in my head.

Fine. Not one test. Six.

I used the money I’d been saving for a community college summer class I don’t even remember wanting and turned our kitchen table into a lab bench. AncestryDNA, 23andMe, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA, LivingDNA, and an academic lab Archer’s cousin had used once for a paternity dispute—I ordered all of them. I tracked shipping like people track storms. I logged every barcode number, photographed every vial in Eli’s hand because the ritual made me feel competent.

The results trickled in. One by one, the same chorus, different phrasing: parent‑child match. 50% shared DNA. Ethiopian and West African components evident in both mother and child. Family networks threaded between us like kintsugi—the gold fill in the breaks.

I built a binder because paper is proof in houses like my mother’s. White spine, clear sleeve, tabbed sections. I labeled it ELI’S TRUTH because I wanted to see the words every time I opened it. Screenshots, PDFs, certified copies arriving with raised seals, a log of the dates she called me confused to people who used to babysit me for free. I printed more than I needed, because a part of me knew that eventually evidence would have to exist beyond my word.

When I placed the Ancestry report on her nightstand, right next to her reading glasses and the monogrammed hand lotion she buys in bulk, she didn’t even sit down.

“Science gets things wrong,” she said, and did not pick it up.

She walked around the binder like it was a spill on the rug. And still—still—I felt the smallest, most dangerous impulse to convince her. So I did what I should have done from the beginning. I stopped trying to win her. I started documenting her.

And, at night, I wrote to my son.

The journal is green, college‑ruled, the cheap kind with flimsy cardboard covers. I kept it in the sock drawer under Eli’s onesies because it felt like a hiding place a story might trust. For Eli, I wrote on the first page. For when you’re curious or angry or both. For when you need to know that love is not the same thing as telling the truth, but the truth helps love breathe. I wrote what she said, and how it felt, and what time the light hit his face and made his hair look like a halo we didn’t ask for.

The attic box was an accident and an inevitability.

I went looking for the pastel blanket she saved from when I was a baby, the one she likes to mention whenever someone says she doesn’t have a sentimental bone in her body. The storage closet has the pull‑down stairs folded against the ceiling like a secret. A draft breathed dust onto my face when I tugged the cord. Up there, light slanted through a grime‑webbed window and turned everything sepia. I found Christmas decorations and a broken humidifier, a box of letters tied with ribbon—performative nostalgia—and, shoved back against the rafters, a carton so heavy it scraped my palms. DO NOT OPEN, someone had written across the lid in thick black marker a lifetime ago.

The twine had gone crisp with age and snapped under my fingers. I opened the lid and something ancient—paper, perfume, and denial—rose out and wrapped around my head.

Photos first, crisp at the edges and butter soft in the middle. A girl smiling like she didn’t know she’d practice not smiling for the rest of her life. Long dark hair, a messy joy in her posture, a face I knew like my own in a version I’d never met. Penelope. Next to her, arm around her waist, a Black man with crinkled eyes and a low, patient grin. Handsome in a way that made you look twice and then a third time to figure out why your chest was a little warm.

I flipped. The two of them on a stoop with paper cups, laughing mid‑motion. The two of them holding hands, nobody pretending they didn’t. The two of them with a little girl perched on his knee, braids slicked with oil, and my mother’s mouth replicated on a smaller face. I didn’t recognize the house. I recognized the feeling: the uncurated part of someone’s life.

Beneath the photographs: a birth certificate, folded and refolded until the creases threatened to give up. Penelope Marie Edwards. Date. Hospital. Mother: Clara Edwards. Father: Leonard Davis. My breath snagged.

Edwards. Not Quinn. Leonard Davis. Black. My grandfather.

There were letters beneath that, tied with ribbon the way people tie up hope. The handwriting was elegant, almost smugly so. Dates from the late sixties spilled into the seventies. The words passing and dangerous and safe appeared often enough that I stopped and pressed my fingers into the carpet to ground myself in something that wasn’t ink.

At the bottom sat a small, leather‑bound diary. I shouldn’t have read it. I did. My mother’s hand, younger and more rounded at the edges, poured across the pages in careful curls. She wrote about Leonard, about the way he listened and how his laugh came out of him without checking itself first. She wrote—and here the pen dug deeper into the paper—about Clara, about keeping secrets to hold onto respectability, about the easy doors whiteness opened, about train tickets and names and new lives that start with lies because you’re told that’s the price of safety.

Between pages, brittle and waiting, a letter in a different hand. The script was stiff, the tone not. If they find out, it’s over… You are a Quinn now. You are white. If they find out about Leonard, about them, it’s over. Signed: Clara.

We have a word in our family for the way Penelope moves through rooms: composure. Holding the letter, I realized the better word is performance.

At the very bottom, under postcard stacks stamped in places I’ve never been, a Polaroid slid into my lap. I almost missed it; time had curled it into itself. I flattened it gently with my palm. A bus in the background—Greyhound, destination window flickering Celler County, GA—and in front of it, a very young Penelope, seventeen at most, her hair long and her hand at the small of her back like she’d been walking all day. Her belly rounded beneath a loose dress. Pregnant. My mother has always told me she met my father in college. Married at twenty‑one. Baby at twenty‑two. I was nineteen, holding proof that timeline was made of smoke.

I checked the baby monitor in my pocket. Eli slept in a soft, wheezy rhythm that untied and retied my spine. Celler County, Georgia. I’d never heard of it.

I put everything back in order, the way a thief would who intends to steal again.

Her family is a web. I called a strand.

Delilah Davis—forty‑four, my mother’s estranged cousin—lived somewhere two towns over if the old directory in my grandmother’s desk could be trusted. The number miraculously still worked.

“Hello?” Cautious, but not cold.

“Hi.” My voice came out too soft. I cleared it. “My name is Vivian Quinn. I’m Penelope’s daughter.”

Silence, then a small, rueful laugh. “Well. That’s a surprise.” A beat. “What can I do for you, Vivian?”

“I found some things,” I said, and in the mirror over the console table I watched myself decide not to apologize for it. “A birth certificate. Letters. Pictures. A name: Leonard Davis.”

A sigh that sounded like someone letting a secret out of a tight dress. “So she finally told you.”

“She didn’t,” I said. “I found it.”

“Then good for you.” A pause like a blessing. “Yes. Leonard is—was—your grandfather. My uncle. Clara’s husband. It was an open secret with us. Your mother… she wanted a different life. Clara pushed her toward passing—called it safety. We called it shame.”

“And Celler County, Georgia?” I asked, the Polaroid burning a square against my thigh.

“She stayed with an aunt there for a while,” Delilah said. “Seventeen. Eighteen. Came back with a new name and a plan. I didn’t ask questions. People got disowned for less.” The sound she made wasn’t quite a laugh. “What are you looking for, honey?”

“Truth,” I said. “Enough of it that my son doesn’t grow up inside somebody else’s hiding.”

Delilah’s voice softened. “Then you’re already doing better than most of us.” She hesitated. “Your father… I don’t know those details. Only that there were always gaps in the story big enough to drive a bus through.”

We spoke for forty minutes. She told me about Leonard’s hands, about the way he could fix radios and fences and the hurt in a person’s shoulders without making you feel observed. She told me about Clara’s fear, about how fear turns into rules and rules turn into cages if you let them sit long enough. When we hung up, I sat at the kitchen table and stared at Eli’s bottle drying on the rack and decided that if my mother loved cages, she could keep hers. My son was going to have air.

The plan came together like all good plans do—slowly, then all at once.

I borrowed a high‑resolution scanner from a friend in the design department at the community college. I spent nights digitizing everything I’d found: the photos, the letter from Clara, the birth certificate with its raised seal, the Polaroid’s grain. I adjusted contrast carefully and let the scratches remain; truth shouldn’t look brand new. I built a timeline on clean white paper: Penelope Marie Edwards, born 1976. Leonard Davis, Black. Clara Edwards, white. Polaroid, circa 1993. Celler County, GA. Name change. Marriage to David Quinn, 1997. Eli born, 2024. Six DNA tests.

I re‑printed the lab reports. I made a separate section for screenshots of text chains and group chat whispers my cousin Amy forwarded me from the family’s private threads—We’re keeping Vivian in prayer. Penelope says the baby…—with dates and timestamps and the names blurred enough to be decent and clear enough to be undeniable.

I bought a brick of manila envelopes and a brand‑new black pen. On each front I wrote the name of a person my mother cared about impressing: Aunt Jennifer (the let’s not get into that collector), Uncle Steve and his wife, the cousins who stopped liking photos of Eli’s toes after the first week, the neighbor who prays for everyone else’s soul at book club. I tailored the contents to the audience. For the stubborn, more documents. For the curious, more photographs. For the kind, the timeline and one picture of Eli with a note: Meet your cousin.

I didn’t include a letter from me. I wanted the evidence to speak in the voice my mother hears best—cold, official, irrefutable.

I mailed them from three different post offices over two days. It felt criminal and righteous. It felt like making a thing real by putting it into the world.

The first replies came fast.

Vivian, what is this? from a cousin who once brought me a prom corsage because my date forgot.

Is this… true? from Aunt Jennifer, the text blinking and then followed by another: Please call me.

From a number I didn’t have saved—I always wondered about your granddad. She never let me talk about him. I’m sorry, sweetheart.

A handful were pure fury: How could you do this to your mother? And one or two were exactly what I expected from the people who think silence is class: nothing at all.

Through all of it, Penelope moved like a woman in a museum, careful not to brush against the art.

Until the envelope with her name on it slid through our mail slot.

I was making formula while Eli flapped his hands at his mobile. She picked up the stack of bills and catalogs, thumbed them into order, and froze. Penelope Davis Quinn in my hand on the front. For a second, I thought she’d rip it up the way she did the first test.

She didn’t.

She opened it. She slid out the contents, slow as if they might bite. The restored photograph sat on top: Penelope at twenty with Leonard Davis at her side, both of them bright with a happiness that had never been allowed to age properly.

All the muscles in her face stopped doing what they’d been trained to do. Her mouth parted. Her eyes glassed over. The color left and returned to her cheeks in one tide.

She put the photo back in the envelope like a person handling a loaded weapon and left the kitchen without speaking.

I didn’t follow. For the first time since I was a kid, I understood how she uses silence. And I decided to use it better.

That night, Eli slept hard, mouth open, fists loose. At midnight, I heard the soft mechanics of a life uprooting itself: a suitcase hinge, drawers sliding, the barely‑there thud of shoes placed carefully in a line. I got up and cracked my door. The light in her room was on. She moved methodically, folding, choosing, not looking in the mirror.

I closed my door and leaned my forehead against the wood and let the strangest feeling wash over me: grief for a woman who chose a lie so entirely she thought it was oxygen. Then anger welled up to meet it and the two canceled each other out like a math problem that ends in zero. What was left was a steadiness I hadn’t known in months.

In the morning, her phone screamed itself hoarse on the kitchen island. She didn’t answer. Messages stacked in the notifications window—Call me. This can’t be real. Penelope? She moved past them and into her room and came out with a suitcase and a tote bag. She didn’t glance at Eli in his bassinet. She didn’t look at me.

At the door, her hand paused on the knob. She turned her head, just enough to catch me in her periphery. For the first time in my life, her eyes held nothing I could use—not anger, not triumph, not even disdain. Just a blankness like a stage after the audience goes home.

She walked out.

The latch clicked. The house exhaled for the first time in months.

My cousin Amy knocked five minutes later, as if we’d rehearsed the timing. She had a baby blanket in her hands, homemade and too bright. She didn’t ask about the envelopes. She didn’t ask where Penelope went. She stepped around the suitcase tracks on the entryway tile and went straight to Eli, who woke, blinking, and offered her a slow, gummy smile. She picked him up with the gentleness of somebody who understands breakable things.

“She’s really gone,” Amy said, not quite a question.

“She is,” I said. My voice surprised me by not shaking.

Part of me wanted an ending with fanfare—apologies pressed like flowers between the pages of regret, a confession at family dinner, some public, cinematic collapse of a facade. What I got was quieter and meaner and more honest: a woman who had spent her life performing whiteness making an exit in the only way she knew how—without saying the line she was never going to say.

I put water on for coffee. The kettle began to hum. Eli grabbed Amy’s necklace and held it like a talisman. My phone pinged and pinged and pinged. I let it.

I had a binder on the table. I had a box in the attic whose contents had stopped being secrets and started being history. I had a son who would grow up knowing exactly which parts of him came from who. I had questions left—a bus, a county in Georgia, a father whose name might not be the one on my birth certificate.

I had time.

Part 2 of 2

Penelope didn’t send a new address. She didn’t leave a note. The only proof she’d been a mother in our house—beyond the tasteful fruit bowl and the silent rooms—was the divot a suitcase wheel left in the foyer rug and the dent in the trash can where the first DNA report had landed like a verdict.

For a week, the doorbell kept churning out people who didn’t know what to do with their hands. Aunt Jennifer arrived with a ham like it was currency for absolution. Uncle Steve stood on the porch, hat in hand, and whispered that he’d always suspected something but suspicion isn’t the same as courage. My phone bloomed apologies and defenses, confessions that used the word complicated like a bandage.

Amy came every afternoon and took Eli outside to watch the leaves shiver. He had learned to giggle—an honest, surprised sound that cracked my chest open in the gentlest way—and his laughter made our fence look less like a boundary and more like a trellis.

At night, when he finally gave in to sleep, I opened my binder and my journal and the scanned folder labeled ATTIC — RESTORED. I looked at the Polaroid again, the bus window stuttering Celler County, GA, and my mother’s hand on the small of her back like she was steadying more than her body. The picture made a noise in my head I couldn’t ignore. Whatever else I had excavated, this was a fault line running under my own name.

Delilah answered on the second ring.

“Do you know who lives in Celler County now?” I asked, no preamble left in me. “Aunts. Anyone who’d remember that time.”

“Some of us,” she said slowly. “My mama’s cousin, Bernice—she’d have been your grandmother’s age. There’s a pastor’s wife who keeps records like they mean something. What are you thinking, Vivian?”

“I’m thinking,” I said, looking at Eli’s soft profile on the baby monitor, “that the story I was given doesn’t balance out.”

We drove down on a Wednesday that had the decency to be clear. I packed too much—diapers, wipes, an extra outfit, two bottles, a backup pacifier for the backup pacifier—and Amy laughed and then didn’t, because she recognized packing like that: a hedge against the suddenness of life.

The highway unspooled. Fields replaced billboards. Celler County turned out to be less a destination than an accumulation of smaller nouns—gas stations, porches with swings, a courthouse whose clock had given up keeping time, a diner that smelled like bacon and disappointment.

Bernice’s house sat under a pecan tree like it had been born there. She opened the door with her shoulders squared and her mouth already grim. Then she saw Eli’s eyes and something in her face loosened two notches.

“Lord,” she said, and her voice softened, “you’ve got Leonard’s look.” She turned that softened gaze on me. “And you’ve got his stubborn.”

We sat at her kitchen table and drank sweet tea that made my teeth ache and sifted forty years out of a Tupperware bin. Church programs with names circled. A newspaper clipping yellow as toast about a bus accident outside town. A photograph of Clara at a bake sale, smile stitched a little too tight. And—carefully, like it might be wrapped in glass—Bernice slid me a picture I didn’t know how to take.

Penelope sat on a sofa upholstered in a floral so busy it could hide stains and sins. Her hair was loose for once. Her belly—mine once—was round beneath a borrowed dress. Next to her, a boy not much older than her own seventeen or eighteen. He had the kind of beauty that gets boys into trouble and then out again: open face, shy smile, a steadiness you’d miss if you didn’t know to look for it. His hand hovered an inch above her knee like both a promise and a permission request.

On the back, in Clara’s scolding cursive: P. with M. — absolutely not.

“Marcus?” I said it like a test.

Bernice’s nod was a small benediction. “Marcus Lee.”

“Is he—?” The question snagged. My throat had been waiting for it.

“Gone,” she said gently. “Car wreck, winter of ’97. Black ice on Highway 12. He’d moved up to Atlanta to work at a garage. Came down to visit his mama and didn’t make it back.”

I pressed a hand to my chest like I was catching something falling through me. “My mother always said she met David in college,” I said. “Married quick. Then me.”

“Because it was quicker,” Bernice said, not unkind, “than telling the truth.”

She reached for another folder, this one slimmer. A church record book, the leather cracked. Pastors wives keep better books than pastors; everyone knows that. Inside, a page handwritten in neat blue ink:

Edwards, Penelope Marie — confession of faith, 1993 (with child). Referred to aunt, M. Pearson. Left for Atlanta, spring 1994. Returned summer 1997. Married David Quinn in August. Child born October—Vivian Marie.

My birth certificate says October. The marriage license says August. The math, for once, was not metaphor.

Amy had gone quiet beside me. Eli, in her lap, gnawed on her knuckle like it was a teething ring he trusted more than rubber.

“Did David know?” I asked the air, because Bernice could only give me paper.

“Men like David,” Bernice said, fingertips smoothing nothing on the table, “know what they love and what they don’t. He loved your mama’s ambition and the way she fit into a room where deals were made. He didn’t love questions with long answers.”

The courthouse was a square of brick and resignation. The clerk raised eyebrows at my request and then, maybe in defiance of the way the world looks at girls with babies, went to fetch the archived records anyway. We left with copies—a marriage license, notarized, with a date that made my stomach drop and then settle, a hospital record from a prenatal clinic just outside Celler County listing patient: Penelope E. and, handwritten in the margin, father unknown.

Driving back, Eli slept the way babies do when the car tells them a story: steady and repetitive and humming. Amy traced her finger along the marriage license, her nail catching on the raised seal.

“What are you going to do?” she asked.

“Keep writing,” I said. “And tell him everything when he asks.” I glanced in the rearview at the curve of Eli’s cheek. “And decide what to do with the name ‘Quinn.’”

The family blew apart and came together along lines I didn’t predict.

Aunt Jennifer, who had always liked seating charts more than conversations, showed up with lasagnas and offers to drive me to the pediatrician. Uncle Steve sent me the number of a lawyer “in case you want to get some things on paper.” Three cousins I hadn’t seen since I was twelve texted pictures of their grandkids and said, He’s beautiful. We were wrong. Amy’s mother called to apologize and ended up crying for the better part of fifteen minutes, not only for me but for the girl she’d been who chose silence because it seemed like loyalty.

The other side did what the other side always does. Silence. Averted eyes at the grocery store. One email that used the word unseemly in a paragraph so tight with righteous grammar it squeaked.

It turned out relief could be a kind of grief. I missed the simpler stories even as I was glad to have set them on fire. I missed the idea of a mother who would have defended me at the hospital—who would have said my grandson without looking for the nearest mirror. Missing the idea didn’t bring back the woman. It just made the quiet around her absence more honest.

Delilah called to check in and ended up telling me about Leonard’s hands—how he repaired radios by listening before he ever touched a wire. “He could hear where the static was thickest,” she said. “Then he’d start there.” I wrote that down in the journal under a heading I didn’t know I’d been creating: What I Want Eli to Know About the Men He Comes From.

I added Marcus to that list. What I had: a photograph, a name, a winter road. What I imagined: the way he looked at my mother in that picture—like someone whose love had not yet been turned into a liability.

And because I believed in symmetry, I texted David Quinn.

I know, I wrote. I have records. If you ever want to talk about the truth instead of the performance, I will meet you where you are. I won’t pretend for you. I will be kind if you can, too. He read it. Two pulsing dots. Then nothing. It felt less like rejection than like muscle memory—his, not mine.

I didn’t expect Penelope to come back to the house. She doesn’t repeat scenes unless she’s certain of her lines. She texted once, two weeks out:

Please stop sending things to my friends. This is humiliating.

I typed and deleted three replies before I settled on the only one that felt like it belonged to the person I’m trying to become.

Truth humiliates lies. Not people. I won’t send anything else. The truth is traveling on its own now.

She didn’t answer. But three days after Eli turned seven months and learned how to clap for himself, she sent a second message.

I’m in Celler County. I need you to come. Church on Miller Street. Tomorrow, 2 p.m.

I called Delilah. She sighed the sigh of a woman who has played every role in a family drama and is tired of the costume changes. “Go,” she said. “Take your baby. Wear shoes you can stand in for a while.”

The church looked like every Southern church that’s ever taught more than it admitted—white paint, steps that needed repair, a kitchen that could produce a funeral spread on an hour’s notice. The sanctuary was empty except for the soft drone of the air conditioner and a woman at the piano playing chords that didn’t want to be hymns.

Penelope sat three pews from the back. She had aged ten years in two weeks. Not in the way makeup can fix. In the way that happens when a person drops a mask and the face underneath hasn’t known air in decades.

She turned as if she’d heard the thought. Her eyes swept Eli, then me, then the binder under my arm. She flinched at the binder like it was a weapon. Maybe it was.

“Thank you for coming,” she said. Her voice was fine china in a sink.

I didn’t sit. “Why here?”

She gestured, a tiny irritable flick of her wrist. “Clara was married here. So was my aunt. So was—” She closed her eyes. “They keep records.”

“And confessions.”

A flare of the old heat. Then it guttered. “I came to… look.” She glanced toward a wall lined with framed black‑and‑white photographs of people smiling in ways that meant it. “I wanted to see what I—what we—threw away.”

Amy, who had come and was now making faces at Eli that made him kick his feet hard enough to thump the pew, cleared her throat in a way that meant I’m here if you need to step away. I nodded without looking.

“I found Marcus,” I said. “On paper. In a photograph. On a highway.”

Penelope’s mouth compressed. “He wasn’t—” She stopped, and in the space where the lie would have once unfurled, another kind of sentence assembled itself. “He was kind,” she said, like she was at the far end of a tunnel speaking into a can attached to a string. “He would have married me here. He asked. Clara said I would break our necks on that choice.”

“And David?”

She swallowed. “He liked that I could be what he needed. He never asked about dates. I never offered them.” She looked at Eli, then away, the motion abrupt. “I thought I was keeping us safe.”

I let the words sit between us until they stopped performing and started sounding like breath. “Safe from what?”

“The look people give you,” she said, and for the first time in my life I heard the girl inside her speaking straight through her. “The look you learn to anticipate so you can beat it to your own face. The way doors close quietly. The way ‘no’ gets said without lips moving.” She laughed, and the sound cut. “And then I became the person doing the looking.”

There it was. Not apology. Not yet. But a mapping.

“The thing about safety,” I said, “is that if the price is your soul, you’re just renting a nicer cage.”

She winced. “I know,” she said. “Now.”

We sat. Eli reached for the air and grabbed a dust mote. I took a breath that traveled all the way to my feet. “Here’s what’s going to happen,” I said, because for once the plan didn’t feel like a threat but like a path. “I’m changing my name. Not all the way. Eli and I are going to be Davis‑Quinn. We are not deleting the parts of us that don’t fit your mother’s letter.”

Penelope closed her eyes as if I had poured cold water over her head. “All right.”

“You are going to tell your friends—your bridge club, your charity board—that you lied. To them. About me. About yourself.” I didn’t raise my voice. I let the words do the heavy lifting. “If you choose not to, I will not correct the record for you again. Silence is expensive. You can pay for it if you want to. I won’t.”

She flinched, but she nodded—the smallest, truest nod I’ve ever seen her make.

“And,” I said, and here the part of me that is my father’s daughter, my grandfather’s granddaughter, steadied my mouth, “when Eli is old enough to ask you why you tried to make him a mistake, you will tell him about Leonard. And Marcus. And Clara. And the cost of being the kind of woman people reward. And you will ask him what he needs from you then. Not what you need from him.”

Her hands had been folded in her lap this whole time. She opened them as if they ached. “Will you ever forgive me?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said, and the honesty shamed nobody. “I know I will keep Eli safe from the part of you that confuses love with erasure. I know I will build a family around him that tells the truth even when it sits like a stone in the mouth. I know if you want to be in that family, you will have to practice a new language.”

We left it there. Not a reconciliation. An agreement to stop pretending we were at war about the small thing when the real thing was enormous.

Outside, the air was bright and ordinary. Amy loaded Eli into his car seat while I leaned my head against the warm roof and let my bones rest for the first time since the hospital’s humming lights.

“Do you feel better?” she asked.

“I feel… accurate,” I said, and somehow that was better than better.

The weeks turned into a pattern that made sense. I enrolled in classes that would push me toward the degree I’d delayed. I filed the paperwork for our name change and cried in the car after the clerk stamped it because a stamp should not feel like a sacrament, and yet. Aunt Jennifer learned how to fold a stroller in under ten seconds and strutted around the farmer’s market like she was newly elected mayor. Delilah mailed me a recipe card in Clara’s hand for a sweet potato pie that used too much nutmeg, and I decided to make it anyway because history isn’t improved by skipping the parts that make your tongue tingle.

David Quinn emailed two sentences the day the county paper ran a small notice about the name change in a bureaucratic column nobody reads unless they’re getting married or sued.

I did know. I’m sorry. I’m sorry in the way a person is when being sorry doesn’t fix anything. It wasn’t nothing. I printed it and filed it under For Eli — When He Asks About David.

Penelope didn’t come back to the house. She sent a postcard from a coastal town with a picture of a lighthouse trying its best. On the back: I told them. It was not dramatic. It was not gracious. It was true. — P. It wasn’t an apology. It was the only thing she had that resembled one. I put it in the binder because the binder had stopped being a dossier and started being an archive. And archives are just a way of saying, we were here, and this is what we carried, and this is how we put it down.

On Eli’s eight‑month day, we stood in a park with grass like the color green meant it. Amy took a picture of us under a tree—his fist full of my collar, my smile not pinned in place but rising from somewhere actual. I sent the photo to Delilah and Aunt Jennifer and, after another minute of choosing, to Penelope. She replied with a single line that surprised me by not making me angry.

He looks like everyone we come from.

“Yes,” I texted back. Just that.

Before I slept that night, I opened the green journal and wrote across a clean page:

Eli,

Here is what I know now that I didn’t know when you were born under lights that hummed like bees.

You come from a line of people who learned how to be smaller to survive. Some of them got so good at it they mistook the shape they’d made for who they were. Some of them—Leonard with his listening hands, Marcus with his kind eyes, Delilah with her calling things by their names—left the door open for air. We are going to stand in that doorway and let the truth move through us, even when it raises goosebumps. Especially then.

Your skin is not a question. Your name is not an apology. Your joy is not a debate. When people forget that, we will remind them. When we forget, we will forgive ourselves and correct course.

I will tell you the story of how your grandmother packed a suitcase instead of unpacking a lie. I will tell you the story of how she came back, not as a mother exactly, but as a woman trying to learn a new language in a mouth that had only practiced silence. If she keeps learning, we will keep letting her take the next lesson. If she stops, we will not be her chalkboard.

When you are old enough, I will take you to a small church on a street named for a man who probably owned other men once, and we will stand in front of a wall of photographs and you will see faces that look like yours and mine in different ratios. I will say their names out loud so that the room knows what to do with us. You will clap for yourself the way you do now, wildly impressed by the miracle of your own hands. I will not tell you to quiet down.

You were the truth that blew our house open. You were also the reason the light finally got in.

—Mom (Davis‑Quinn)

I tucked the journal back under the onesies like it belonged to both places—what’s written and what’s worn. The house was quiet in the way that means rest, not restraint.

Before I turned off the lamp, I slid the binder one shelf higher. It didn’t need to be within reach anymore. Not because the world had changed its mind about who we are, but because I had. Truth would sit on that shelf like a book we knew by heart. We wouldn’t have to clutch it to our chest every time we walked from one room to another. That’s the thing about telling the truth long enough: eventually, it starts telling you back.

And when I finally slept, I dreamed not of fluorescent lights or garbage cans or buses, but of a little boy clapping for himself under a broad, forgiving sky.

END!

News

They Charged Me Rent While My Brother Lived Free—Then I Bought a House in Cash

They Charged Me Rent While My Brother Lived Free—Then I Bought a House in Cash Part One The envelope slid…

Fox News host Jesse Watters reveals which Hollywood star cursed him out in an airport lounge

Fox News host Jesse Watters says a chance encounter with actor Shia LaBeouf in 2019 turned ugly when the Hollywood…

When Late Night’s Avengers Unite – A Historic Moment on The Late Show!

Late-night television just had its most iconic crossover ever. Jimmy Fallon, Seth Meyers, John Oliver, and Jon Stewart all appeared…

While Stephen Colbert drained up to $50 million annually from CBS with his woke comedy crusade, Sydney Sweeney simply wore a pair of jeans—and added $200 million in market value to American Eagle. Turns out, silence in denim is more profitable than shouting in a suit.

Stephen Colbert’s Costly Comedy vs. Sydney Sweeney’s Profitable Simplicity Recent financial reports draw a sharp contrast between two very different…

Greg Gutfeld Crashes Late-Night TV: Fallon’s Riskiest Guest Yet?

Brace yourselves — Greg Gutfeld is coming to The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, and insiders say it might just…

“This Is Who He Really Is!” — ABC News Anchor Suspended After Karoline Leavitt Exposes Shocking Comment — And the 14-Word Reply That Left Millions Stunned

He thought it was just a private post. It took just one screenshot. One broadcast. And one fearless woman who…

End of content

No more pages to load