My Mom Laughed: “No Wonder You’re Still Single at 31” — She Had No Idea About My Secret Wedding…

Part One

The champagne flute shattered against Italian marble, golden liquid spreading like my mother’s shock across the pristine floor. Three years, she whispered, her perfectly manicured hand still suspended where the family photo had slipped through her fingers. But how could I explain that her cruelty had given me the greatest gift, a love she never deserved to witness?

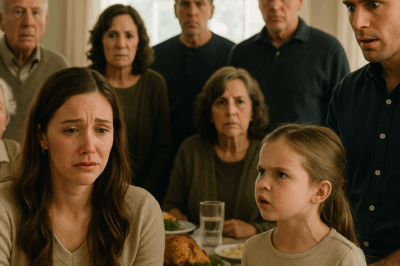

My name is Sophia, I’m thirty-one, and on that Thanksgiving evening, standing in my childhood home watching my mother’s face crumble, I felt the weight of every secret I had carried. The dining room still smelled of rosemary and judgment. The mahogany table was set for twelve with the good china my mother only used to impress people who mattered. I had never mattered. Not when I was seven and she forgot my school play. Not when I was sixteen and she missed my valedictorian speech. And certainly not when I was twenty-eight and fell in love with someone she would have called “beneath us.”

“Sophia is still single,” my mother had announced earlier that evening, not for the first time. She said it like a diagnosis—chronic, unfortunate, possibly contagious. My sister Victoria sat across from me, her surgeon husband’s arm draped possessively over her shoulders, their two perfect children playing quietly with iPads that cost more than my first car. My brother James and his beauty-queen wife held each other’s fingers as if their wholesomeness might lift them above the rest of us. And then there was me, the family’s favorite cautionary tale.

“You know,” Mom continued, sipping her wine with theatrical concern, “Mrs. Henderson’s daughter just married a federal judge. Harvard Law. They honeymooned in the Maldives.” She paused, letting the comparison sink in like a needle. “But I suppose not everyone can be that fortunate. Some people are just meant to… focus on their careers.”

The way she said careers made it sound like a consolation prize, as though my position as a creative director at one of Seattle’s top design firms was just a thing people did when no one wanted them. Aunt Patricia nodded sympathetically. “Don’t worry, dear. My hairdresser knows a nice accountant. Recently divorced, but only once.”

That’s when my mother laughed. That particular laugh she’d perfected over years of charity luncheons and country club verbenas. “No wonder you’re still single at thirty-one,” she said, gesturing at my simple black dress, the only one of mine that had ever appeared in family photos. “You don’t even try anymore. When I was your age, I’d already given your father three beautiful children.”

“Too picky,” Victoria chimed in softly enough to be cruel. “Too independent,” Aunt Patricia added, delighting in the chorus.

“Too happy,” I said.

Silence. Forks hovered midair. Even the children looked up from their screens.

“Actually,” I said, setting down my water glass with deliberate calm, “I’ve been married for three years. You just weren’t invited.”

The family photo—the one from Victoria’s wedding where I stood at the edge, a ghost on the periphery—slipped from my mother’s fingers. It hit the floor with a crack that split my carefully posed smile right down the middle.

“That’s impossible,” she breathed. “I would have known. Someone would have told me.”

I pulled out my phone, swiping to the photo I’d looked at a thousand times but never shown them. There we were: me in a simple white sundress, wildflowers in my hair, barefoot on a beach in Olympic National Park. Beside me, Marcus—his smile brighter than the setting sun behind us, his hand in mine, our matching white-gold bands catching the light.

“June fifteenth,” I said, passing the phone to my frozen father. “Three years ago. Sixty guests. People who actually love us.”

Victoria found her voice first. “You’re lying. This is some desperate attempt for attention.”

“His name is Marcus Chun,” I continued, watching my mother flinch at the surname. “He’s a pediatric nurse. Saves children’s lives every day. His parents own a restaurant in the International District—the one you called ‘ethnic’ when you drove past it. They catered our wedding. Best dim sum you’ve never tasted.”

James pushed back from the table as if physically distancing himself from my audacity. “You kept this from us for three years. Your own family?”

“Family?” The word tasted metallic. “Was it family when Mom told me no man would want a woman who worked late? When you all took bets on whether I’d end up alone with cats? When Dad called me the ‘practice child’ and thanked God you two got it right?”

My father’s face flushed. “Sophia, that’s not—”

“Marcus proposed after six months,” I said over him, not loud, just determined. “In his parents’ restaurant, with his whole family cheering. His mother cried and called me her daughter. His father said he’d never seen Marcus so happy. His sister asked me to be her kids’ godmother before we even set a date. They didn’t care that I worked late. They celebrated it. They celebrated me.”

My mother stood slowly, gripping the table’s edge. “You married some nurse. Without telling us. Without asking.”

“Asking what?” I asked. “Permission? Blessing?” My laugh came out sharp. “When have you ever blessed anything I’ve done? When I graduated summa cum laude, you asked why I wasn’t dating. When I got promoted, you said successful women intimidate men. When I bought my condo, you worried I was ‘settling into spinsterhood.’”

“We only wanted what was best—” Aunt Patricia started.

“No,” I said. “You wanted what looked best. A doctor, a lawyer, someone from the club. Someone you could brag about at brunch.”

I stood, matching my mother’s height for once, meeting her eyes without blinking. “Marcus volunteers at free clinics on weekends. He reads to sick kids during his breaks. He learned to cook my grandmother’s recipes from that stained cookbook you threw away. He holds my hand during scary movies and brings me coffee in bed every Sunday. He sees me—actually sees me—not as a project to fix or a disappointment to manage, but as someone worth choosing every single day.”

Victoria’s husband shifted. “Still… three years of deception.”

“Deception?” I slipped my wedding ring from the chain I’d worn around my neck and slid it onto my hand. I hadn’t hidden it tonight to protect them. I’d hidden it to protect my moment. “The only deception was pretending you were the family I needed.”

Around the table, the tableau of my childhood remained intact: abundance laid out on polished wood, something essential missing. The old clock on the mantel ticked louder than any heartbeat. In spite of everything—the years of coldness, the little pities, the loud judgments—some part of me had come hoping for a life raft, a small confession of love misdirected. Instead, I felt the subtle click of a door closing inside me, the sound of courage, not bitterness.

“Why did you come?” James asked, genuine curiosity slipping through the practiced disapproval.

I held his gaze. “Because I’m pregnant. Twelve weeks. And I realized this baby deserves to know the truth about both sides of their family. Even the side that would have tried to ruin the happiest day of my life with conditions.”

My mother sank back down. “Pregnant.” The word came out strangled.

“Due in May,” I said. “Marcus painted the nursery last weekend—soft yellow with clouds on the ceiling. His mother’s knitting blankets. His father’s building a crib. They throw their arms around me every time they see me. Like I’m a gift.” My voice trembled then, not with fear but with something I hadn’t let myself feel in that house since I was little: longing.

“Do you know what that feels like?” I asked the room. “To be celebrated just for existing?”

Tears ran down my mother’s face, tracking through the powder and privilege. “We could have—”

“Would have what?” I asked, gentle but immovable. “Planned a wedding you could control? Invited people I don’t know? Made me wear your dress and your expectations? Told Marcus he was lucky to have me while whispering the opposite to your friends?”

I gathered my coat. The room blurred as much from the overhead lights as from the weight of all we hadn’t been. “His parents are having Thanksgiving tomorrow,” I said. “Twenty people crammed into their apartment, kids running everywhere, three languages in the air. Loud and messy and perfect. Marcus saved you all seats just in case. His mother makes extra food every year, hoping I’ll bring you. I always tell her you’re ‘busy.’ She doesn’t know the truth—that you’re not busy. You’re just broken.”

I reached the door and paused. Behind me, the breath of the room didn’t change. “You want to know the saddest part?” I said without turning. “When Marcus proposed, the first thing he said wasn’t ‘I love you’ or ‘Marry me.’ It was: ‘You don’t need their approval, Soph. You never did.’ And he was right.”

“Sophia, please,” my father said, his voice finally unsure. “Let’s discuss this rationally.”

“There’s nothing to discuss,” I said. “You can choose to accept that I chose love over your approval, or you can keep that photo on the floor with all your other broken things. I’m done apologizing for being happy.”

My hand tightened on the knob.

“Will you…” my mother asked, each word costing her something, “will you send pictures of the baby?”

I looked back at her—the woman who spent my entire life measuring me against a yardstick she’d bought at an expensive store. Marcus would say yes, I thought, and the softness of that realization surprised me. “Marcus would say yes,” I said aloud. “He believes people can change. He sees the best in everyone—even families that don’t deserve it. It’s one of a million reasons I married him.”

I pulled a card from my purse and set it on the hall table with a steady hand. “Our address. Do with it what you want.”

The November air outside was sharp and clean. I sat in my car with the engine off, phone in my lap, fingers hovering over Marcus’s name longer than necessary, the way you sometimes hold onto a moment before you let it carry you forward.

Coming home, I typed. Bring Biscuit to the door. I need maximum waggly therapy.

Already waiting, he replied. Your mom’s hot chocolate ready. Extra marshmallows. You’re brave, baby.

As I pulled into our apartment complex—a quirky mid-century building whose creaky floors and odd angles had charmed me the first day—I saw them in the window: Marcus holding Biscuit, both faces pressed against the glass, our two small lighthouses in the storm. I parked crooked and ran. He met me at the door, pulling me into his arms while Biscuit spun himself into a furry cyclone around our ankles.

“How did it go?” he murmured into my hair.

“About as expected,” I said into his chest. “But I told them everything.”

He pulled back to look at me, his thumbs warm against my cheeks, wiping tears I hadn’t realized were falling. “And?”

“And I’m home,” I said. “Where I belong.”

He kissed me then, right there in the doorway with the neighbors probably watching, and I thought about my mother’s dropped photo—how sometimes things have to shatter before you can see what really matters.

“Come on,” he said, taking my hand. “Let me tell you what my mom said when I called her about tomorrow. She’s making extra dumplings just in case your family comes. She says hope costs nothing but means everything.”

I laughed—really laughed—for the first time all evening. “Your mother’s an optimist.”

“She’s right, though,” he said, resting his palm on my belly. “Hope does cost nothing. Your family just never learned how to afford it.”

That night, surrounded by our chosen life—the photos from our real wedding covering every surface, Biscuit’s toys scattered on the floor my mother would have called beneath us, Marcus’s scrubs draped over the chair because he saves lives while she saves face—I stopped paying the price for someone else’s love. Real love—the kind that celebrates your victories and cushions your falls, that builds cribs and knits blankets and makes extra dumplings “just in case”—that love doesn’t cost a thing. It just requires showing up as yourself and finding people who think that’s more than enough.

Three years ago, on a beach with sixty people who understood, I married someone who knew I was worth celebrating in secret until I was ready to stop hiding in public. Tonight I finally was. Tomorrow I’d tell his family about the baby. Next week we’d argue over names and whether “little Biscuit” was acceptable for either gender. Next month, we’d find out which. And maybe—just maybe—my mother would find our address card and choose hope over habit. But even if she didn’t, I had already found my family. They were waiting for me at home with extra marshmallows and endless love.

Part Two

Thanksgiving at the Chuns’ felt like stepping into a story I’d once read as a child and assumed was fiction: doors that opened before you knocked, voices that layered instead of competed, warmth that came from people rather than thermostats. Marcus’s parents, Min and Hana, lived in a third-floor walk-up in a building that smelled faintly of sesame oil, garlic, and wood polish. When we arrived, Min was leaning out the kitchen doorway in a flour-dusted apron, calling something in Mandarin to a cousin while Hana wrapped scallion pancakes on the dining table like a magician pulling rabbits from a hat.

“You’re here!” Hana cried, abandoning the pancakes to cup my face in her small, strong hands. “Aiya, you’re glowing. Pregnancy suits you. Marcus, move, move. Let her sit.” She smacked her son’s arm affectionately and led me to the head of the table as if I were emissary and queen.

“Where is your family?” Min asked, not with accusation, but with the concern of someone who assumes love is a matter of logistics.

“They’re… considering,” I said, which felt both true and kind.

“Then we eat first,” Hana declared, as though the sequence of eating and forgiving had been established by some benevolent deity who never worried about seating charts.

The Chuns’ apartment held twenty-four that day and could have held more. Children zigzagged between the legs of aunties and uncles while a cousin balanced a tray of steaming dumplings perilously close to someone’s resting shoulder. Cantonese swerved into Mandarin which swerved into English and then back again while I let the music of it burrow into some hollow that years of polite silence at my parents’ table had carved.

“Tell us your news,” Hana said, when plates were already (impossibly) both empty and full again. “Min and I only pretended to be surprised yesterday when Marcus called. We suspected the way you kept falling asleep on our couch after two bites of dinner.”

I felt a laugh spill out like a shaken soda. “May,” I said, and Min actually slapped the table, eyes wet. Hana counted on her fingers, muttering zodiac signs under her breath as if calculating the baby’s fortune.

“Rabbit,” she declared, triumphant.

“That was last year, Ma,” Marcus said, choking on a dumpling. “This one’s a dragon.”

“Good,” Hana decided. “Strong. Stubborn. Like mother.” She winked at me, and for the first time, I liked being called stubborn.

After lunch, we cleared the table with the choreographed chaos of people who have always made room for one more. I washed dishes while an aunt told me, in the kindest way, that my wrists were too fragile for scrubbing and shooed me to the sofa. Min pulled out a photo album—the kind with sticky plastic that makes small tearing sounds as pages turn—and pointed at a girl who looked like Marcus in long hair and a dress, her front tooth missing, her grin uncontained. “My sister,” he said softly. “She died when I was nineteen. She would have loved you.”

“I would have loved her,” I said, and meant it.

By early evening, when the babies had finally surrendered to sleep and the teenagers had clustered on the floor to watch something funny and rude, Hana came back from the kitchen with a small box wrapped in gold paper.

“For you,” she said. “For when you tell your mother again, properly.”

“I already told her,” I said, rubbing the crease where worry had lived. “She dropped a photo on the floor and asked for pictures of the baby.”

Hana nodded as if she’d expected that. “Then this is for when you are ready to tell her you forgive her. Not now,” she added quickly, raising a hand as my mouth opened to protest. “Later. After you remember that forgiveness is a gift you give yourself, not someone else.”

“Ma’s gotten philosophical in her old age,” Marcus whispered, and Hana smacked him again lightly, a punctuation of love.

At home, we put the box on the mantel next to a driftwood frame that held our wedding photo and a Polaroid of Biscuit mid-air, ears like paper airplanes, his face the personification of joy.

“Hana’s right,” Marcus said later, when we were cocooned under blankets on our too-small couch, a Hallmark movie doing its earnest best to sell a storyline we didn’t need. “Forgiveness isn’t an apology’s reward.”

“I’m not there yet,” I said, pressing my cheek to his shoulder. “But I’m not nowhere.”

“Not nowhere,” he agreed. “That’s a lot of somewhere.”

December came with pineapple buns from the bakery on Jackson and with a card in my mailbox with my mother’s handwriting on the front. Inside was a photo of the three of us—me, age four, missing a shoe; Victoria, perfect posture even then; James, a baby attempting to escape our mother’s lap—and a note that said: I don’t understand. I am trying. —M.

I stared at it for a long time. The old me would have read “trying” as “not enough” and discarded it the way she had discarded so many almost-apologies. The new me—new not because of marriage or pregnancy but because of marrow—put it on the fridge with a magnet shaped like a dumpling and texted Marcus: Small thaw. No earthquakes.

We drafted a message together, me deleting and rewriting, him holding the edges so my words didn’t shake: Thank you for the card. We’re doing well. The baby is healthy. If you want to try again, there’s a community holiday dinner at the Chuns’ church. Loud. Free. Welcoming. No speeches. You could come. No pressure. We pressed send and went to the grocery store and argued sweetly over pomegranates as if we had not just let something risky into the room.

She came.

She stood outside the church basement in a camel coat, the one from Paris that she never wore to our house because she didn’t want Biscuit’s hair on it. For a long moment, she didn’t move. Then Hana saw her and lit up as though someone had given her a new daughter as a surprise. “Come,” Hana said, looping her arm through my mother’s before my mother could decide whether to be proud or mortified. “We need more hands.”

My mother spent the next forty minutes in an apron, learning to fold dumplings from people who had never heard of the club and would not care if they had. The first one she folded looked like a wet envelope. The fifth one looked like a dumpling. She made eye contact with me for the first time that night when Biscuit licked her ankle and she hissed, “Oh for heaven’s sake,” and then laughed at herself for hissing. I handed her a towel. She took it.

During cleanup, she hovered near the door again, hand on her coat like it might explode if she put it on too quickly. “That child,” she said awkwardly, gesturing with her chin toward a girl in glitter sneakers and a tutu who had run the entire evening like a marathon, “she’s… spirited.”

“Like her mother,” I said, and Marcus said “and like mine” and Hana said “and like me” and the three of us laughed, not at her but around her, a circle big enough for a person to step into if she wanted.

“I brought something,” she blurted, as though afraid she might lose the courage to continue if she did not say it fast enough. She reached into her bag and took out a small white box with a gold ribbon. Inside, nestled in tissue, lay a knitted sweater—soft yellow, clouds stitched across the chest. The clouds were slightly crooked, one of them looking like a cauliflower, the other like a sheep.

“I started it when you were born,” she said, eyes fixed on a point somewhere near the radiator. “It was supposed to be for your first child. I forgot. No. I didn’t forget. I resented you for not being faster. That’s ugly to say. But bitterness is ugly. I found it last week, half-done. I finished it.”

The room didn’t spin. The baby didn’t kick just then. Heaven didn’t open and anoint the sweater with absolution. But a thread inside me loosened in a way that felt less like unraveling and more like being able to breathe.

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it with an ache I had been avoiding.

Hana took the sweater, turned it over like a quality inspector at a boutique, and said, “You learned mattress stitch,” which made my mother stand straighter than any praise I’d ever watched her receive at a luncheon.

We walked my mother to her car together. She hugged Hana awkwardly, Marcus sturdily, and me lightly, as if testing the weight of a new bridge. “Send a picture,” she said, “when… when you feel like it.” It was progress. Not promise, but progress.

The day our daughter was born, the city was wrapped in a soft drizzle that made everything seem gentler. Labor went like a song you know you’re strong enough to carry—hard and holy, relentless and ridiculous. Marcus counted my breaths and told bad jokes. Hana sat on the plastic chair and prayed in Mandarin so fast her words became a blanket. Min brought a thermos of congee and yelled at a resident for putting a chart on my bed like I was a table.

When they put our child on my chest—a person and a miracle and a burrito all at once—I thought: Oh, so this is what love looks like when it is small enough to hold and big enough to flood a life.

We named her Juniper Mei, and everything else in the world rearranged itself to make space for the fact of her.

Marcus texted my mother a single photo: my hair a mess, my face wet, Juniper squawking like a dignitary denied more honors, Marcus’s hand visible like a promise. She’s here. She’s healthy. Sophia is a warrior.

The first visitor to arrive who was not medically required to be there was my mother. She stopped two steps inside the room and made a sound like a person who had left something heavy by the curb and discovered someone else had turned it into art. She approached the bassinet the way you approach a sleeping animal you want to trust you. Juniper snuffled and sneezed. My mother laughed—one small unpretty sound that was better than any of her practiced ones.

“May I?” she asked, and I nodded because boundaries are a fence you can also hang a gate in.

She washed her hands longer than necessary. She picked up my daughter with elbows like question marks and then remembered how to uncurl them into exclamation points. She whispered nonsense that sounded like apology and worship and fear and math. When Juniper farted with the confidence of a CEO, my mother startled and then burst out laughing in a way I had never seen, head thrown back, mouth open, eyes closed. Laughing like a girl.

She stayed for twenty minutes. She left before sentiment could become performance. On her way out, she pressed the cloud sweater into the bassinet, then stopped and pulled it back, then set it in the bassinet again like a ritual.

“I mailed the address card to myself,” she said in the doorway without turning around. “So I wouldn’t lose it.”

“Good,” I said. “It’s a good address.”

Juniper turned us into new people slowly—like water on rock, patient and unstoppable. Marcus learned diaper origami. I learned to nap with one eye open. Biscuit learned that humans sometimes shriek at 3 a.m. for reasons unrelated to fireworks.

The first month, my mother texted photographs of cloud-colored yarn and YouTube links to baby massage techniques and nothing else. I sent back pictures of Juniper’s yawns and my destroyed ponytail and—once, spontaneously—one of Marcus asleep on the floor with the baby on his chest, both of them drooling. She responded with a heart, then corrected it: “A heart feels glib. That looks like peace.”

One day in May, a large box appeared on our doorstep. Inside was a baby rocker that could have launched a small satellite. The note said: From your father, who still doesn’t have the words. We put it together that night while we ate cold noodles out of the container and argue-flirted over the tiny allen wrench. When we set Juniper in and it swayed, she blinked like a monarch tasting freedom. I texted a video to my father. He responded with a thumbs-up and then, after ten minutes, sent another text: Saw the video 37 times before I figured out how to reply. Your mother says I should say it’s nice. It’s nice. I cried and laughed in equal measure.

Victoria hovered for a while. She sent a green-bubble text: Our kids don’t need more cousins. I ached for a sister who wasn’t a competition. I set my phone face down and went back to changing a diaper that had ambitions beyond its station.

James delivered a casserole that contained too much onion and too much sincerity and said, “I’m learning how to be a brother who doesn’t get a medal for being baseline decent.” “Keep learning,” I said, and hugged him longer than the joke deserved.

Aunt Patricia came over wearing a fully sequined cardigan and taught me a trick for getting baby poop out of muslin. “Club soda,” she said, “and secrets.” She kissed my temple and whispered, “I always liked you best,” which was not true but also not false.

By autumn, my mother could spend an entire hour at our apartment without rearranging a blanket. She had been practicing not exerting control the way some people practice scales—that is, daily, with resignation and hope. She brought food sometimes—not the theater of a roast but Tupperwares of congee, carefully labeled: rice thicker for cold days, thinner for fever, ginger for tummy, no ginger for rash.

One evening, as she washed bottles at our sink like a person paying penance with dish soap, she looked over her shoulder and said, “I don’t know how to be a grandmother without being a tyrant.”

“Practice,” I said, handing her a towel. “Start small. Ask to hold, don’t just take. Compliment the mess. Bring oat milk.”

She snorted. “Don’t push it.”

We laughed, and in the spaces between our laughter, forgiveness snuck closer, a cat who had decided our house was worth visiting again.

It happened one Saturday at the park when Juniper was ten months old and had decided walking was for people who didn’t own knees. We were sprawled on a blanket with snacks that would become sand and sand that would become snacks. My mother arrived late on purpose, so she didn’t have to say she was trying. She sat next to me and didn’t critique the way I wore my hair.

“I don’t understand many things,” she said, watching a toddler in a dinosaur hoodie attempt to share a stick. “But I understand this.” She nodded toward Marcus at the swings, hair ridiculous in the wind, voice an incantation of “up, down, up, down.”

“Understand what?” I asked, leaning back on my hands, sun warming my shoulders.

“That you chose a good man.”

I swallowed a lump that tasted like childhood. “I did.”

She angled her face toward me slightly, eyes hidden behind sunglasses that had seen more tears than I had allowed myself to suspect. “I didn’t know how to celebrate a daughter who didn’t look like me,” she said. “So I punished you for that. I’m sorry. Apologies don’t untie knots. But I can stop pulling.”

I let the quiet witness her words before I entrusted them to memory. “Here’s what I can offer,” I said softly. “You can be in our life if you can be in our life as it is. Loud. Mixed. Marshmallow-heavy. We will not edit ourselves to perform for the version of you who keeps score.”

She smiled, small and rare and real. “I am not good at math,” she said. “But I am learning to count dumplings.”

We took a new family photo that winter—our family, chosen and earned and expanded. In it, Marcus stands behind me, his hands on my shoulders. Biscuit sits in front like a small, alert potato. Juniper lunges out of frame because she is her own person. Behind us, Hana leans into Min, and my mother stands with her fingers hooked into the pocket of my coat as if she is anchoring herself not to an old version of me but to the present tense. My father smiles the careful smile of a man still surprised by joy but willing to risk it. James makes a face that will make us laugh for years. Victoria sends a text that says, Nice picture and then another that says, How do you make the baby’s hair do that? and then another that says, Fine. I’m coming over for dumplings. Progress never looks like a brochure, but it can look like extra chairs and an auntie counting clouds on a sweater to calm herself when the baby screams.

On our mantle, that new photo sits in a driftwood frame beside the one of us on the beach, the rings catching a sun my mother didn’t see and didn’t need to. The old photo from Victoria’s wedding—with my barely-there smile at the margins—stays hidden in a drawer not because I’m ashamed, but because some frames belong to the past.

Sometimes, in the late hours when the house is soft and Juniper squeaks in her sleep like a door that hasn’t decided whether to open, I pad to the kitchen for water and stop by the mantle. I touch the glass. I think of an address card placed on a hall table like a dare and a promise. I think of dumplings folded by hands that used to point instead.

I think of a laugh—my mother’s laugh—once weapon and now, occasionally, blessing.

The wedding my mother never attended was perfect precisely because she wasn’t there. But the life that followed, that she now steps into carefully, imperfectly, faithfully—dough under her nails, marshmallow on her coat, genuine curiosity in her eyes—that life is perfect in a way that invites rather than excludes.

Love did not ask me to shrink. It asked me to grow into myself and then make room for others to grow, too.

If our daughter ever asks why we kept our wedding a secret, I’ll tell her the truth: we protected the beginning of our story the way you shield a match in the wind. And when the flame was strong enough, we stopped shielding and started lighting other candles. Her grandmother’s was one of them. It took time. It took boundary and breath and extra dumplings. But in the end, even a house that smelled of rosemary and judgment could learn the scent of hope.

And hope, as Hana says, costs nothing—but when it arrives, it changes everything.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money’

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money,’ Brian Kilmeade passionately defended Erika Kirk on…

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent. CH2

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent Part One The rosemary lamb went…

BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions in his final statement and unexplained evidence have shocked the public: Is Robinson blaming someone else?….read more below

💥 BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions…

“I Stared At The Photo—My Son Did This?” — A Sheriff’s Father Breaks His Silence On Utah’s ALLEGED KILLER

At a $600,000 family home in Washington, Utah, a veteran lawman dialed the number no parent imagines: he turned in…

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire : Ava Raine, the daughter of Hollywood legend Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, has ignited one…

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale. CH2

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load