My mom convinced my boyfriend to marry my sister. She told him, “She’s stronger and a better fit for you.” I was crushed when I found out, so I moved away to start fresh. Years later, we reunited at a lavish party I hosted. And when they saw my husband, their faces went pale, because he was…

Part One

My mother has a way of making brutality sound like good advice.

“You’ll thank me one day,” she said, patting the back of my hand as if she hadn’t just detonated my life. “Some women are built for partners with ambition. Some women are…independent. There’s no shame in that, Sophia.”

Independent. It landed with a soft thud and a barbed tail, like every other word she stuffed with implication. Independent meant alone. Independent meant the girl in the corner of the family photos. Independent meant the computer on my lap at family gatherings, the degree my mother never learned to pronounce, the way she always said coding with a light cringe.

The day she told me Eli had chosen Amber, she served lemon squares and wore the color of serenity. She even smiled. “He came to me confused,” she said, smoothing napkins that didn’t need smoothing. “He’s going places, Fee. He needs someone who can stand the heat.”

“Amber?” I asked. My voice sounded wrong, far away. “You told my boyfriend to marry my sister.”

“Don’t be dramatic,” she said, which I’ve learned is what manipulators say when you call their cruelty by its name. “I simply helped him see the truth. She’s stronger. A better fit for his world.”

Eli didn’t meet my eyes at the door. He never did when he felt small, and he felt small a lot for a man with shoulders like a bank vault. “I’m sorry,” he mumbled. “It’s just…your mom made some good points. You’re so focused. You love your work. I need someone—”

“Who loves parties more than production schedules?” I finished for him, and for a moment I saw the boy he’d been, face open and desperate, waiting for someone to tell him what to be.

“It doesn’t have to be ugly,” he said.

“Then leave,” I said. I didn’t cry in front of either of them. I waited until they left, until the screen door clicked and my mother’s perfume evaporated from the hallway, until my father reappeared from whatever room he had hidden in. He opened his mouth and closed it again like a fish washed up in the wrong story.

“I’m moving out,” I told him. “I’ll send for the rest of my things.”

“You don’t have to go so far,” he said, eyes sliding past my face as if my pain was too bright to look at.

“I do,” I said. And then I did.

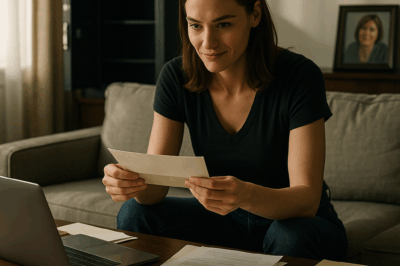

Starting over isn’t glamorous. It’s a mattress on the floor in an apartment so bare your keys echo when you drop them on the counter. It’s eating rice and eggs because you put everything else into the business you’re trying to will into existence. It’s the “Out of Office” reply no one ever sent you, the calendar you fill yourself with scraps of opportunity.

I traded east coast winters for a gray-blue city across the country where there were more cranes than clouds. In Seattle, no one knew the Thompson women. No one knew my mother’s smile or my sister’s laugh or the way their voices synced when they performed the duet of our family story. I changed my number. I sold my car. I carried the one photo I couldn’t throw away—a crooked snapshot of me at fourteen, grinning at a laptop with a cracked hinge as if it were a sunrise.

I built from what I knew. Technology is just organized empathy—understanding what people need and building something that meets that need with as little friction as possible. I put that sentence on my website because it sounded better than “I’m stubborn and broke but good at solving knots.” I did UX audits for bakers and law firms and a yoga teacher with lighting so bad it made enlightenment look like a rash. I designed e-commerce flows that didn’t punish people for wanting to give you money. I learned to brew strong coffee and make introductions and attend networking events without disintegrating.

I didn’t date. Men like Eli existed in every city, shiny and sure until you asked them to stand next to a woman who wouldn’t make herself smaller so they could grow. I chose invoices over intimacy. The women in my co-working space were my companions—Amberly who could sell glass to a window, Hoa who ran numbers like prayers, Lila who was building a platform for women-owned farms and taught me how to say no without apology. When I told them my story, they made the good faces—listening, not judging—and then they did what women do when one of us is gutted: they fed me, they emailed me leads, they said, “There’s better.”

I met my husband at a boring breakfast.

At least that’s what it looked like on paper: a healthcare innovation summit at a hotel with carpet chosen by someone who feared joy. There were pastries so pretty they tasted like regret. I had a nametag and ninety minutes and a low-grade headache that had nothing to do with caffeine and everything to do with a calendar overfull of meetings that would not pay my rent.

The keynote went long. The panel moderator used three clichés and a pie chart with no labels. Then a man walked onto the stage who knew how to talk about complexity without making you feel stupid or sleepy. He spoke like a person who had built things and broken them and learned to separate ego from iteration. He talked about encryption as a promise instead of a cage and told a story about his grandmother carrying a paper chart across three clinics because nobody’s systems could speak the language of her breath.

He didn’t have the hair of a tech messiah or the swagger of a founder who had never been told no. He had kind eyes and a jacket he had not fidgeted with even once. When the Q&A started, I asked a question he seemed to like. After, he found me by the ice sculpture that was supposed to be a DNA helix and looked like a drunk barber pole.

“Sophia Thompson,” he said, reading my nametag with a smile. “I liked your question.”

“Adrian Calder,” I said, reading his with a name I recognized and did not place until later. “I liked your answer about designing for dignity.”

“Dignity is good UX,” he said. “You’d be surprised how often people are willing to trade the former for the illusion of the latter.”

We had coffee because there is no safer way to say “prove you’re not an idiot.” He asked what I built. I showed him screens and spreadsheets and a notebook full of ugly sketches. He laughed at my jokes. He listened until he understood and then pushed me to be braver. I asked about his company. He told me stories about hospital CEOs and nurses and a Florida clinic where a hurricane taught their servers how to drown.

He didn’t mention his last name. He didn’t have to. I googled him, and there it was: Calder Holdings, a Pacific Northwest empire that equaled “old money” to people like my mother who think class is something you can purchase if you smile hard enough. There were articles and litigation records and glossy profiles. There were family photos with uptight captions. There was an older brother who had inherited the majority share, and a younger one who made the gossip column.

I expected him to float. He did not. He asked for a second coffee and a copy of my rates. When I emailed my estimate, he responded faster than I responded to people I loved. We started with a pilot—me cleaning up a small product line’s onboarding. I doubled conversion. He sent a message with three words: “Let’s keep going.”

A friend of mine calls what happened after “the slow click.” Meetings stack. Trust grows. Jokes become shorthand. Your calendars begin to match on purpose, not by accident. One day you realize your hearing is tuned to one person in a crowded room. The slow click is safer than fireworks. It does not impress spectators. It builds structure.

We clicked.

He kissed me on a Wednesday after a meeting with a hospital board in Ballard. He had said something about the ethics of AI triage, and I had rolled my eyes at the CFO who wanted to Pennywise the problem, and in the elevator after he laughed in the relieved way of a man who knows you are on his side. When the doors opened, he didn’t move. Neither did I. He had the manners to ask and the confidence to know the answer.

I told him about my mother on a Sunday afternoon when it rained in that Seattle way that pretends it isn’t. We were sitting on the floor of my apartment with takeout containers and my laptop between us as we wrote out a logic tree for a broken patient portal. “My mother believes love is a resource with limited supply,” I said, “and my sister thinks other women’s lives are fitting rooms.” I did not say Eli’s name. I did not need to.

Adrian set his chopsticks down. “My father thought love was proof you could buy,” he said. “My mother thought it was a social contract. Family is a language we learn without agreeing to it.”

We did not fix each other. We did sit in the same room with both of our ghosts and pour them tea and say, “We’re busy. You’ll have to wait.” When he asked me to marry him, there was no kneeling, no choreographed embarrassment. There was a quiet morning on the water and a question asked like a promise: “Do you want to carry this with me?”

I said yes. We got married in a room full of people who had never once told me I was too much or too little. We built a company that made our lawyers nervous and our clients grateful. My mother called twice—once to tell me Amber had a new boyfriend who was “finally your caliber,” and once to say that my aunt’s gardenia bush had died as if this were a shared tragedy.

I saved her number as Silence.

Three years later, in a glass-walled hall filled with people my mother would have practiced lying to, I hosted a party that wasn’t a party so much as a strategy. The Calder Foundation wanted something splashy to announce a new fund earmarked for women-led tech companies in healthcare. I wanted a place to celebrate a cohort of founders who didn’t have time to chase men down golf courses. The venue had ceilings high enough to make bankers whisper and acoustics good enough that you didn’t have to shout to be heard. There were canapés that would make my grandmother weep and a string quartet because I am a cliché and also because Debussy makes people say yes to grants.

We called it the Illuminate Gala because people like events with verbs. It was the kind of night my mother collects magazine clippings about. It was also the first time in a decade she had called me and asked for an invitation.

“Your sister heard about it,” she said, softness coating the sentence like icing disguising a dry cake. “It would mean so much to her to see you. And to me.”

“You can come,” I said. “Bring the people you love.” I did not say their names. I did not plan which smiles I would wear. I did select a dress that made me walk taller.

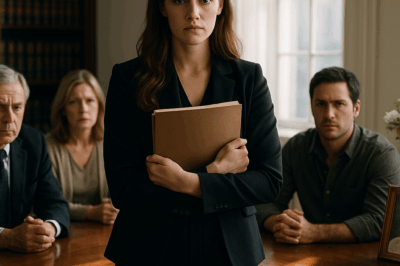

When they entered—my mother in expensive soft colors, my sister in a dress she would have stolen if she couldn’t buy it, Eli at her elbow wearing the expression of a man who just realized his high school reunion was televised—they pretended it was any other party. They complimented the lighting. My mother air-kissed generous donors as if she were the reason we stood in a hall that contained more net worth than my hometown.

Then Adrian walked onto the stage, and the Calder crest glowed on the screen behind him, and they went pale in a way you can’t fake.

My mother whispered it before she could stop herself. “Calder.”

“Good evening,” my husband said into a room that had hushed for him and would have hushed even if his last name had been ordinary. “Thank you for trusting us with your ideas, your money, your stories. Tonight, we’re putting our weight behind women who build bridges in systems designed for gates.”

He spoke in that steady way that made men in navy suits nod and women with product teams lean forward. I watched my mother watch him the way a tourist watches a lion and wonders if their guide lied. I watched Amber stare at his hand, searching for a ring she had not noticed before, thrashing mentally through the names of people she had meant to meet and failed to. I watched Eli do the math that men learn young: how many zeros, how many nods, how many doors.

I waited until the strings began to play again and the donors turned to their next prey. Then I gathered them.

“Mother,” I said. “Amber. Eli.”

My mother’s smile was a precision instrument. “You’ve done shockingly well for yourself,” she said. “Your husband—”

“Is Adrian,” I said simply, watching recognition bloom fully in their faces, “and more than that, he is the majority owner of the firm that holds the mortgage on your new house.”

They didn’t know that part. It wasn’t malice that made me say it. It was context. It was an axis shift you can hear.

Amber closed her mouth because she realized it was open. Eli looked like the wind had changed and he hadn’t dressed correctly. My mother’s hand tightened on her clutch until her knuckles showed white. “I had no idea,” she said. Honesty or performance? With her, the line dissolves.

“You didn’t ask,” I said. “You told me who I was and assumed I would stay there forever.”

“You married into this,” she said, recovering, her voice edged with a familiar contempt. “That’s not the same as building it.”

“Mother,” I said, and years dropped into the space between us like stones into a well. “Look around.”

The room hummed with women whose slides had once been cut from decks to make space for male egos. Founders who coded at three a.m. and pitched at nine and fired a vendor at noon when he called them sweetie. There were unrepentant napkin-sketchers and spreadsheet sorcerers and shy geniuses flanked by louder friends. Adrian, in a conversation of laughter and shaking hands, half-turned to find me with that small tilt, the one that says I am a fixed point.

“Did you bring Eli to show him what he lost?” I asked softly. “Or to see what you did?”

“He made his choice,” my mother snapped.

“No,” I said. “You made it for him. For both of us.”

Eli finally found his voice. “Sophia, I—”

“You broke my heart,” I said politely, because this was my party and I was not going to swear in Calder Hall. “And then you mistook my silence for consent. We were young. You were weak. I was, too. My mother likes to collect weaknesses and spend them. I’m not mad at you anymore.” It was almost true. “I’m busy.”

He swallowed. “You look…happy.”

“I am,” I said. “Human, with days that crack at inconvenient places and nights where the baby won’t sleep and mornings that smell like coffee and possibility. Happy.”

My sister’s smile had stopped being a weapon and started being a mirror. I saw myself at twenty-two in her, a different kind of gullible. Affairs and influence had smudged her, but there was still a girl who had wanted to be loved when our mother had only taught us how to be impressive.

“Your husband,” Amber said, voice barely audible. “He’s—”

“He’s my partner,” I said. “In business and in breakfast and in the mess of raising a human who thinks sleep is oppressive. He is also the older brother of the man you married.”

There it was—the second wave of pale. Of course they knew the name Calder. Everyone with ambition in our coast cities does. But they had not traced “Adrian” to “older brother,” had not realized that the boy my mother had nudged into Amber’s life shared blood with the man who chose mine.

“You married—” Amber began, and then stopped. I saw it in her—the recalculation, the slow churning of a mind that has been used to manipulation realizing it has met a story that cannot be spun. I should have felt triumph. What I felt was a tired tenderness. We were both sisters in the story my mother wrote. I had escaped by erasing the page; she had underlined and underlined until the paper tore.

“Walk with me,” I said to her, surprising us both.

We stepped away from our mother and the donors and the way men in suits condescend when they want to be seen graciously. In the side gallery, a cascade of light poured down from a skylight, glancing off the glass of an installation that looked like a frozen rainstorm.

“How have you been?” I asked.

My sister’s face did a thing I’d never seen it do in public: it told the truth. “Tired,” she said. “And small. And angry.”

“Angry at me?” I asked, because I had been the eldest longer than I had been a person sometimes.

“Angry at myself,” she said. “And at mom. And at how easy it was to take what you built because she told me it was on sale.”

We stood there breathing under a rain of glass and found a thing we had not had since we were girls who hadn’t known yet that love could be conditional. We found the ability to sit with pain without turning it into a weapon or a performance.

“If you want to do something that belongs to you,” I said, “I’ll help you write the plan. But not if you are doing it to ‘prove’ something to her.”

She nodded, eyes wet in a way that did not threaten mascara. “I do,” she said. “Something that makes my hands tired and my head quiet.”

“There’s a bakery on Sixth,” I said. “Owned by a woman named June who needs a manager who can do schedules and scold men for touching the display with their bare hands. Start there. Learn how flour works. Learn the smell of morning. Learn how to go to bed because the bread won’t bake itself at four. Then we’ll talk.”

She laughed, brief and surprised. “You would help me.”

“You’re my sister,” I said. “Not my mother.”

When we returned to the hall, my mother had positioned herself next to a man from a bank with a name like a law firm. She looked up as we entered and I saw something I had never seen on her face—uncertainty. She knew the game we were playing now did not have the rules she had written.

I poured coffee for a philanthropist who wanted to fund the mentorship program and answered a dozen questions about security protocols and knew when to direct a famous actress with a checkbook toward a founder who would make her cry with a story that deserved tears. I watched Adrian watch me—gladness at eye crinkle level, pride at posture level, a wordless check-in across a room full of noise.

At midnight, when the string quartet packed their instruments and the men in suits slouched like dogs who had been very good for a very long time, he found me on the balcony. The lake was a patient sheet of black. The city beyond was teeth and promise.

“You were magnificent,” he said, kissing the top of my ear like a secret.

I leaned into him. The gold of the lights reflected off his cufflink, the one with the Calder crest that made men suck in their stomachs and women straighten their spines. I had not taken his last name because I needed it. I had taken it because we had both needed something that made our names mean less and our work mean more.

“Did you see their faces?” I asked, not gloating, simply assessing. “Did you see my mother’s?”

“I did,” he said. “I also saw your sister’s.”

“She wants to bake bread,” I said.

He smiled. “We need bread more than we need parties.”

At home later, when I washed my face and pinned my hair and slid between sheets that felt like forgiveness, my phone lit up with two messages. One—a text from a number saved as Silence: “I did what I had to do.” Old script. I turned the phone face down.

The other—a photo from my father: a thrift store paperback, worn and ridiculous, titled How to Say Sorry with the caption, “Page 32 is very good.” I laughed so hard I cried a little. I texted back a heart and a photo of my left hand with the little grooves from my wedding ring imprinted in my skin: proof of belonging that never chafed.

Somewhere, Eli was deciding whether to keep playing the part he’d auditioned for in my mother’s theater. Somewhere, my mother was deciding how much power she had in a world where her currency no longer worked. Somewhere, my sister was looking up bakery supply wholesalers.

I lay there listening to my husband breathe and thought about the thing the therapist had told me that I’d put in my pocket like a coin for later. We spend a long time thinking a door is a wall until someone puts a doorknob in your hand. The hard part isn’t opening it. The hard part is stepping through and not turning around to keep explaining why that room was unlivable.

If you ask me what happened to me now, I will say this: my mother convinced my boyfriend to marry my sister. She told him my sister was stronger and a better fit. I was devastated. I moved away. I built something. Years later, I hosted a party to shine lights on women who build. They came. They saw my husband. Their faces went pale, because he was the man my mother had always wanted my sister to marry, the one she thought only she could acquire, the one she had underestimated because he had never needed her smile.

He was Adrian Calder—the older brother of the man they chose over me, the majority owner of the business they genuflected to, and my partner in a life they had no keys to.

And me? I served coffee and wrote checks and rocked a baby in a hallway while a founder pitched a solution that would save women’s lives. I kissed my husband and my sister’s flour-smudged cheek and the top of my father’s head the week he finally said, “I was wrong,” like it weighed something.

I looked around the rooms I had built with my hands and my stubborn and my heart, and I thought, not “I won,” because that’s a game with too few chairs and too many losers, but “I am here.” Which is the only victory that lasts.

Part Two

The morning after the gala tasted like the end of a thunderstorm—ozone and quiet. Calder Hall had been stripped of its light and music; the flowers had found new homes in hospital lobbies and community centers. I woke to a houseful of empty glasses and the kind of tired you earn, not the kind that defeats you.

Adrian brought coffee with honey, the way I pretend is medicinal. “I liked your speech,” he said, leaning on the doorframe. “Especially the part where you casually notified your mother that the bank owns her kitchen.”

“That was petty,” I said into the mug.

“That was context,” he corrected, and I loved him more for the difference.

My phone hummed itself toward the edge of my nightstand. Two dozen messages—investors, founders, three journalists. One from my father: Proud of you. The music was nice. Two from Zoe, both screaming in emoji. And a text from an unknown number I hadn’t saved but recognized anyway: You could have told me who he was.

I stared at the little gray speech bubble and watched it go away. My mother hadn’t learned how to apologize in words. She learned how to blame by implication.

By noon, the first headline had landed: THE CALDER FUND BACKS WOMEN WHO BUILD. They used photos where I looked taller than I am. There was a paragraph in the third column about the “surprise appearance” of my family. Then there were the photos I hadn’t anticipated—my mother’s controlled expression at half-mast, Amber’s smile in free fall, Eli adjusting a tie he wasn’t wearing.

I wasn’t interested in their humiliation. You can’t build a life on somebody else’s shame; the foundation cracks. But I also wasn’t going to sand down what happened in that room for anyone’s comfort. There’s a difference between revenge and accountability. One tastes like sugar that melts. The other is fiber; it stays with you and makes you stronger.

The calls started two days later. My mother, then a family friend, then an aunt I liked in theory. There was hand-wringing in triplicate about “impressions.” I didn’t pick up. Accountability doesn’t schedule follow-ups.

Amber texted the third day: Do you really know a woman named June who sells out of cinnamon rolls by nine a.m.?

Sixth and Vine. Tell her Sophia sent you, but don’t say my last name. She charges more if she knows there’s a story attached.

A minute later: She told me to come back at four a.m. tomorrow. Is that a joke?

June’s punch clock is the sunrise, Am.

She sent a skull emoji. A few hours after that, a photo arrived: a hand, my sister’s, dusted in flour, a tiny blister forming where a wooden spoon rubs wrong. There was something like pride in the way her fingers curled around a measuring cup.

The week turned practical. Foundation grants require paperwork regardless of the poetry on gala napkins. I spent three days with a team evaluating a women-led company that had figured out how to reduce imaging appointment wait times in rural clinics without adding a single employee. Adrian ran to the corner for soup when I forgot to stand up. He didn’t ask; he left it where my eyes would fall on it when they finally did.

On Thursday, my father called. “Your mother has been…quiet,” he said, as if that word alone might undam a river. “She keeps washing the good glasses.”

“How’s her hand?” I asked. My mother’s hand had a way of finding tactic and theater.

“She’s not broken,” he said, with a small humor that let me laugh. “Amber called this morning—sounded…different. Flour does that.”

“Flour?” I asked.

“She found the kind of work that doesn’t clap for you while you’re doing it,” he said, and I put a little extra sugar in my coffee without being sure why.

He cleared his throat. “Sophia, there’s a thing at the small art museum—remember the place where you stared at that Calder mobile for an hour in seventh grade? They have a lecture on modernist design Saturday. Want to meet me there?”

I did not remember his noticing the hour. “I’ll fly out Friday night,” I said.

He was already seated when I arrived, and the room smelled like old velvet and cleverness. The speaker talked about balance, about how it requires not stasis but motion in place. You find stability by moving around, not by freezing. My father didn’t look at me while the presenter spoke, which is how some men apologize—their eyes showing they’ve stayed.

We ate soup in the café after; he let me order for both of us and didn’t complain about the kale. “I’m thinking about selling the house,” he said, spoon suspended over porcelain. “Too big. Too many corners that know my secrets.”

“Do you need help?” I asked, which is different from “I’ll fix it.”

“I need your permission to not ask your mother,” he said dryly. “But I have it regardless.”

“You don’t need my permission to live your life, Dad.”

“Then consider this notice,” he said. “I’m taking a class on Tuesday nights. They make you weld.”

“Does Mom know that?” I asked.

“She thinks we’re in therapy,” he said, and then he grinned like a boy who just put a frog in his pocket.

We walked the length of the exhibit afterward. There was, indeed, a Calder mobile—a different one than the one in my memory, but with the same impossible grace. My father tilted his head the way men tilt at birds and art. “He made balance out of imbalance,” he said. “Huh.”

“Huh,” I said.

The first time Eli came to my office, security phoned in a whisper like he was smuggling me news of a comet. “There’s a Mr. Eli Hart waiting in reception. He doesn’t have an appointment.”

“I’m not a bank,” I said. “And he’s not a meteor.”

I let him sit while I finished a call. When I walked into the glass box we call a conference room because our board likes the word, he stood too quickly and knocked his knee on the table. He still had those shoulders; he’d grown into them in that way men do when they lose things they thought were permanent.

“Sophia,” he said, and I watched him put my married name somewhere he didn’t like. “I…wanted to say two things. I’m sorry and I need a favor, and you can choose the order.”

“You’re not getting to the second if the first is currency,” I said. “But you can say it, and then we can both go eat lunch like adults.”

“I’m sorry,” he said, this time without theater. “I let someone else narrate my life to me. I participated. That’s on me. Not your mother.”

“Both can be true,” I said. “You were weak. She was cruel.”

He nodded as if that balanced something inside him. “I’m leaving Boston,” he said. “It’s not…tenable. I have an offer here—in Seattle—from King Street Health. They want me to run a small product line. I heard you’ve been working in that space. I thought… I thought I should tell you before you read it somewhere else.”

“For a moment, the girl in me—the one who had wept at a rest stop—pressed a hand against my ribs. “Okay,” I said to the woman I am. “Welcome to my city. It doesn’t owe you anything, and neither do I.”

“I know,” he said, and his voice matched his face for once. “I’m not asking you to owe me. I can’t fix what I broke.”

“You don’t get to fix it,” I said. “You can live with it. Sometimes that’s the better medicine.”

A week later, I ran into him at the market on Sunday morning. He was comparing asparagus like it had insulted him; the woman at his side had hair like fat cotton and a baby strapped to her chest with a cloth that said in a thousand languages: I am busy keeping a tiny person alive, please make your decisions quickly. He smiled in a way that was smaller and realer. I smiled back with the version I keep for old friends who don’t get to be new ones again. It was enough.

Amber sent photos that didn’t need captions. A scoreboard scribbled in chalk: Pre-dawn: 5/6/7. Her nails, which had learned to say “work” in half-moons of flour. A loaf that would drive a reasonable human to poetry. I sent back practical magic. A spreadsheet template to track supplier costs. A link to a wholesale buyers group. The name of a landlord who didn’t hide fees in the shadows between clauses.

She once called at four in the afternoon and cried because a man with a portfolio and a meaningful scarf had told her registering her bakery as “artisanal” required a guild membership he could help her with for a fee equal to a month of rent. “He called me sweetheart,” she said. “I think he thought I’d show him the cash register.”

“Make him a croissant with salt,” I said. “Then he’ll know what honest men do with women who underestimate us.”

She laughed. And then, that night: I did what you said. I told him my register works only for customers who pay with humility. He left. June gave me half a smile. I feel…taller?

“This is how it happens,” I texted. “You do a thing with your name on it, and then you do the next thing.”

A month later, she sent a photo that was not for Instagram. Our mother behind the counter, hair scraped into a utilitarian knot, hands sweeping stray flour into her palms like an apology. My heart did a thing I had not prepared it for.

She showed up in heels, Amber wrote. June put an apron on her and told her bread doesn’t care about designer. Mom tried to tell a customer they couldn’t pay with coins. June said, “Diane, money is money.” Mom didn’t leave. She stood there for six hours and didn’t talk to anyone about anyone else’s business. At the end she said her back hurt and she could see why I like it. I don’t know who this person is.

“Motion in place,” I wrote back, thinking of Calder and balance. “Don’t trust it yet. But don’t reject it just because it’s strange.”

My father got sicker in waves. He had not been a man who needed help; his body made him one. We flew back and forth until I could have navigated the aisle blindfolded. I sat with him in the afternoons and read him the news and learned which jokes still worked when pain is metric. He wanted stories. Not about my mother. About how a company gets made out of a notebook and insomnia. About how our daughter calls all dogs “sir” and our son thinks airplanes are birds with jobs.

The last time I saw him, he said, “You married well,” with the ancient meaning, not the dinner-party one. “And he married well,” he added, which made me cry in a way I had not cried for years.

“I forgive you,” I said, and it wasn’t a proclamation or a prize I was handing over. It was a description of the room we were sitting in—two people with a thousand days between them choosing to set down luggage you can’t carry into the next place.

He died like a man who had put his papers in order and left a note on the desk: “This is where I keep the wrenches.”

We buried him under a maple that will be spectacular in October. My mother wore navy and did not perform. She cried in the polite New England way people cry when they think emotion is contagious. Amber held one of my children and did not hand him back. After, we went to the bakery and ate bread without talking much. It was good.

The following spring, the Calder Foundation asked me to host the Illuminate Gala again. “We want the women we funded to feel like they live in a city that cares beyond headlines,” the director said. “Also the donors need to be reminded that they’re buying a seat, not a piece of anyone’s soul.”

The second Illuminate was louder. Women who had been nervous last year owned the room this time. Someone wore sequins unapologetically layered with a hoodie that said PAIN. PIVOT. LAUNCH. I gave a speech Adrian called “more dangerous” and my mother would have called “aggressive,” which is why I did it twice.

We catered the dessert from a bakery on Sixth. A woman named June arrived with her hair in a scarf and her hands clean despite her insistence they never are. She brought a tray of something Amber had invented—chocolate bread with espresso glaze and salt that found your gums in a way that made you swear fidelity. My mother arrived and walked by the dessert table without comment. That alone was a miracle worthy of a plaque.

I saw Eli before he saw me. He was wearing a suit that fit this time and a posture that didn’t beg. He was with a woman who laughed easily. He raised a hand in a small salute. I returned it. This is how adults end stories—without light cues and strings, with civility that costs less than bitterness.

When it was time for the check presentation and the founders stood in a row that looked like a jazz band—improvisational, precise, more fun than certain men thought women were allowed to be—I looked at my mother. She stood with her hands around a program instead of someone’s wrist. She looked…still. And then she did a thing I would have bet against—she came to stand shoulder to shoulder with June.

“Oh,” she said, looking at Amber’s dessert. “People like salt now.”

“People like the truth,” June said without turning her head. “Sugar is too easy.”

My mother nodded, a labor. “I wanted to say…” She stopped, recalibrated, started again. “I don’t have the language you two were born with. I only had the one my mother left me. I used it like it was the only way to say love. It wasn’t.” She glanced at me then at the floor. “I’m late to this language. I’m not fluent. I want to be.”

“Flour helps,” June said. She is not big on hugs.

Amber wiped her hands on her apron and kissed my mother’s cheek. “We start at four,” she said. “You’re not allowed to wear heels.”

The donors were confused and charmed. The room felt possible.

At midnight, after the band played a song it knew we hadn’t asked for and the last guest left with their tote bag and their altered sense of what can be done with collective money, I went out onto the terrace with a plastic cup of very good champagne. The lake did its impression of a meditation app. Adrian put his jacket around my shoulders even though it was barely cold. He has a practical streak I would follow into anywhere.

My mother came out. She did not dramatize her entrance. “I told Eli once that ambition is a house with a draft,” she said. “I think I was talking about myself.”

“She’ll get cold in a draft,” I said.

She almost laughed. “I did.”

We stood like women who are trying to make their bodies describe apologies without asking the other woman to do anything with it but notice. After a long minute, she said, “You could have married him.” She nodded toward the ballroom where Adrian was listening to a founder explain a product she loved. “You didn’t pick him because of anything I taught you. You didn’t pick him to prove a point. You picked him because he sees you when you walk into a room.”

“Yes,” I said.

“I wanted to pick your life for you because I did not trust you with it,” she said, and there was no honey in the sentence. It broke something and healed something at the same time. “I was wrong.”

“Thank you,” I said. People overuse those words; here they were the exact size. “That doesn’t give you a key back into every room. You know that.”

“I do,” she said. She turned to go and then looked back, a late addendum catching on her tongue. “You are…a better mother than me. I see that. I’m relieved.”

“You taught me what not to do,” I said. It sounds cruel unless you’ve spent your life deciding whether to be honest or polite and finally learned how to be both. “That’s a gift I chose not to return.”

She went back inside. I finished my champagne. Adrian came out and kissed the place my skull meets my neck. “You okay?” he said.

“I’m…”

“Motion in place?” he offered.

“Balanced by moving,” I said, and he laughed because he’s the kind of man who remembers what you say when you’re showing him something that matters.

We danced then, just us, no strings, no floor-swept gowns, no audience. It looked like swaying. It felt like Europe.

Later, in our kitchen with our shoes off and the house pretending it wasn’t expensive, I opened a drawer and took out the photo of me at fourteen with the crooked laptop. Our daughter toddled in with a wooden spoon like a scepter. Our son followed with the serious face he uses when he organizes toy cars by imagined horsepower.

“Want a story?” I asked them. They nodded, a coordinated tyranny. “Okay,” I said. “Once there was a girl who thought her value came one way and then found out there were a thousand ways to be valuable.”

“Did she fight a dragon?” my son asked hopefully.

“She learned how to tell a dragon from a shadow,” I said.

“Did she win?” our daughter asked. She is impatient with process.

“She found a door she didn’t know was a door and walked through,” I said. “And then she built a porch on the other side so other people could rest when they found their own doors.”

“More,” they said.

“Tomorrow,” I said, and kissed their heads because that is how you end a day you earned.

When I finally turned off the kitchen light, I thought about my mother’s face when Adrian said his name into a microphone and made a room lean forward. I thought about Eli at the market kneeling to show a toddler what good asparagus looks like. I thought about Amber at a sink at four in the morning learning to love the quiet after a loaf goes into the oven. I thought about my father at his welding class, sparks like brief stars from a tool that forces metal to bond.

There are betrayals that break you open in ways that feel like ending. Sometimes they are beginnings dressed as endings, rude midwives to a life you would not have had the courage to choose. One day you host a party in a hall that belonged to other people for generations, and you understand that legacy is a thing you make, not a thing you inherit.

And if your mother shows up and finally learns to wash dishes without commentary, you let her. You hand her a towel. You say, “Thank you.” You do not give her the keys. You keep building.

The look on their faces when they saw my husband? It was shock and calculation and recognition. But what turned them pale wasn’t the name. It was the realization that names don’t matter the way they thought they did. That I hadn’t married up or out or back. I had married right.

That’s the part no one can orchestrate for you. You have to choose it. And when you do, the room changes whether your mother approves or not.

END!

News

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside. ch2

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside Part…

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… ch2

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… Part One…

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… ch2

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… Part One…

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… ch2

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… Part One…

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back. ch2

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back Part One The morning sunlight poured through…

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door. ch2

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load