My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and…

Part One

The order cut straight through the clink of cutlery and the hiss of the stovetop like a thrown knife.

“Alara,” Alex called from the sofa, not looking up from his phone, “bring me some tea. Now.”

I had both hands submerged in the dishwater, wrist-deep in suds and garlic-slick plates. I paused, flexed my fingers against the heat, and inhaled. “Hold on. I’m doing the dishes.”

“What?” His tone sharpened, incredulous, as if I’d announced the laws of gravity no longer applied in our living room. “Stop that and bring me the tea—quickly. Can’t you follow simple orders?”

I let the suds slide off my knuckles in slow, deliberate rivers and turned toward the kettle. Before I could set it on the burner, a second voice—deeper, lacquered in sugar—floated over from the living room.

“Actually,” Mrs. Whitmore said, tapping crumbs from a plate she’d foraged from the back of the refrigerator, “make it sweet coffee. Turkish style. The good kind.”

She said “good” like “obedient.” She always did.

I glanced at the mountain of plates, at the dishrag drooping over the sink like a spent flag. “There are so many—”

“Leave them for later,” she trilled, slicing a fork through the stolen cake. “Just do what we say.”

“Useless wife,” Alex said without looking up, and the words landed with the flat sound of a palm slap.

I know people who can recite their life stories as if they were stitched neatly across the back of a sampler. Mine had frayed in more than one place, threads pulled by other hands, names knotted by other people’s preferences. My name is Alara. I am twenty-eight years old. I am a working mother. I am married. I live in a house that is not mine, that sits on land that feels like someone else’s rule. I have a son—four years old—whose laugh is the only sound that reliably reminds me who I am.

We live in Alex’s parents’ home now—a decision announced by Alex as if he were reading a weather report: inevitable, inconvenient, unchangeable. It was supposed to be “for a while,” in the soft fog of grief after my father-in-law’s death. “My mother needs us,” Alex said. “We’ll all pitch in.” I had believed him. I had wanted to believe him. In the months that followed, I learned that grief and control can wear the same perfume.

The earliest months were a blur of casseroles and respectability. Then the casseroles stopped, and the demands remained. Cooking. Cleaning. Working the front register at my family’s coffee shop on Main twelve hours a day because winter makes people believe caffeine is a coat. My efforts, met with nothing but scorn. Meals left untouched, or “corrected” with salt and commentary.

“The stir-fry is so half-hearted,” Mrs. Whitmore would scold, pushing grains of rice around her plate like little failures. “Make it from scratch. The right way. Not this… busywoman’s version.”

“I’m busy and can only make simple things most nights,” I’d say, each time trying to keep my voice as level as a countertop.

“That’s why I hate backtalk,” she’d snap, and the conversation always ended where it began—her voice filling up the room, mine finding ways to use less space.

Once, when exhaustion knocked my patience loose, I dared to say, “Why don’t you cook, then? You’re a good cook, right?”

She looked at me over the rim of her water glass with the kind of pity that’s actually contempt. “Why would I do housework when you’re here?”

There are only so many times you can fold yourself in half for someone else before your spine remembers it has a job. The cruelty escalated—first enlarged to fill the day, then refined into something worse: a deliberate silence. There is nothing quite like the vacuum created when someone lives in your house and pretends you do not.

We stayed like that for five years. Alex turned thirty-five. I turned thirty-three. Our son grew tall enough to reach the light switch and learned how to spell his name and ask for “more stories,” and the atmosphere in the house never once shifted to something like warmth. Mrs. Whitmore, sixty-three and gleaming, seemed to draw energy from the chill she invented.

I would come home from the coffee shop—flour dusted down my arms, the smell of espresso stitched into my hair—and start to cook just to keep from thinking. That night it was mapo tofu steaming in a clay pot, crispy fried chicken draining on a rack, bell peppers and pork stir-frying with onions until the color of the room changed. I carried the plates to the table and sat down and for a second remembered what a family is supposed to sound like when it eats.

“Bring me the mayo,” Alex said into his phone, and for a half breath I imagined he was talking to someone else. No. He looked at me because he always looked at me for the things he thought did not matter.

“Sure,” I said quietly, passed the squeeze bottle across, and watched his thumb hover over a clip on his screen.

It was weird, the thing that snapped. Not the plate. Not the chair. A thread. A tiny one, somewhere between the ribs. It broke with the clean, painless pop of a string on an instrument that had been tuned too tightly for too long.

We had barely laid our chopsticks down when she said it.

“Clean the toilet,” Mrs. Whitmore announced, as if we were discussing tomorrow’s weather. “Now.”

“What?” The word leapt out of my mouth before I could pull it back.

“Now,” she repeated, tipping her plate so the last fleck of tofu slid into the trash with a wet sound. “It smells.”

“We’re eating,” I said. “Don’t say that. It’s—” I searched for a word that would both satisfy my anger and meet the house’s approval. “Nasty.”

“Nasty like your heart,” she said, smiling a little.

Alex put his phone down finally and looked at me as if I were a smear he’d just noticed on a window. “Apologize to my mother.”

“No,” I said, and the word didn’t even taste like courage this time. It just tasted like the next thing that needed saying.

Voices rose. His. Hers. Somewhere in there I snorted, “If you want the toilet cleaned so urgently, there is nothing wrong with your hands,” and Elaine—Mrs. Whitmore—knocked her chair back in a burst of offended choreography. “You don’t talk to me like that in my house.”

Something settled. Not anger—anger is heat and speed. Something colder. Clarifying.

“I’m not having this conversation,” I said, and left the table.

In my room, the quiet spread itself on the bed like a sheet. I pulled my laptop from under a stack of coloring books and invoices. I typed “download divorce papers” into a search bar and didn’t allow myself to think about what I was untying.

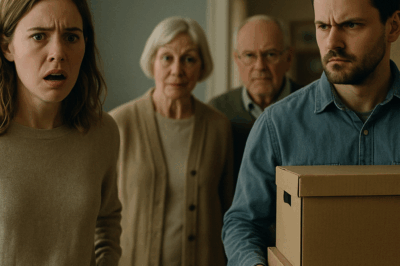

They printed with a sound that didn’t belong in a house at war. I signed where my name belonged and left blank the places that didn’t. I walked back into the kitchen where Mrs. Whitmore had resumed her seat in as offended a posture as she could manage, and Alex had returned to his glowering scroll.

I put the pages on the table like a tray and used the flat of my hand to push them across the wood with a sound that made both of them look up.

“I’m filing these,” I said.

Alex blinked. The smirk—the one he used when he wanted to make me feel twelve—fell down his face like paint left in the rain. “You’re what?”

“Divorce,” I said, and the word didn’t even wobble. “I’m done.”

Silence is an instrument. You can play it. I used it then the way a choirmaster lifts his hand to hold a note. Alex reached for the papers with a laugh and, finding my name in the right places, did not laugh again.

The house reacted like a wound. The days that followed were a carousel of cold shoulders and hot words. A slammed cabinet here. A little sabotage there. Eggs I’d bought and labeled “for me and Eli” used up for a cake I was told I wasn’t welcome to try. And yet—there was something new. It was not joy. It was not relief. But I could feel an unfamiliar muscle along my willpower, and when I flexed it, the room did not change shape around me. I changed shape.

One night, Mrs. Whitmore peered at the dinner I’d set on the table—his favorite, our son’s favorite—like it had personally insulted her.

“You call this food? Even a child cooks better.”

“Eat up, sweetheart,” I told my son, and it felt good to watch him enjoy something I made with the stubborn grace of who I am. “I made your favorite tonight.”

“Playing the perfect mother now, are we?” Alex drawled. “What a joke.”

“I’m trying to make a nice dinner for our son,” I said.

Elaine snorted. “Don’t act high and mighty. You’re a burden in this house.”

It was so funny I almost smiled. “I have been supporting this household for years,” I said, mostly to myself. “I’m not worried about taking care of myself.”

A flicker in Alex’s eye. He knew. Of course he knew. Without my salary, the mortgage would hiccup. Without my small “extras,” his suits would hang on the back of a chair longer than look important. Without my tenacity, the house would revert to a mausoleum: all polish, no life.

They changed tactics. Insult. Ignore. Insult. Ignore. Flatter. Insult. The rhythm itself a bruise.

One afternoon, I passed the hallway and heard them in the living room, their voices hushed and urgent.

“She can’t leave us like this,” Alex hissed. “We need her money.”

“Don’t worry,” Mrs. Whitmore murmured back, and her voice lost all its powder and became steel. “We’ll make her life so miserable she won’t dare.”

I stood there with my palm on the doorframe and felt, for the first time in my life, that I was not alone in the room with them. I was in the room with the truth.

If they wanted war, I would not bring a wooden spoon to it. I would bring a ledger.

I met with a lawyer in a small office above a thrift store. Her name was Sana. She had the kind of smile that made people underestimate her and the kind of mind that made them regret it. “I want a divorce,” I said. “And I want to make sure they don’t get a penny more than the law requires.” Sana nodded. “You’ve been the sole breadwinner?” Yes. “We’ll use that,” she said. “We’ll use everything.”

I documented everything. The insults. The sudden “renovations” of my kitchen. The finances. The days I paid the light bill with tips from the coffee shop because Alex decided the house should invest in a cordless drill set. I recorded their threats with an app I’d been embarrassed to download until the first time my son asked, “Why is Grandma so mad?” and I realized embarrassment has no place in survival.

“You think you can just take our son and leave?” Alex challenged one night, when my bag was packed with documents and courage and a clean change of clothes for Eli. “How will you support him?”

“I’ve been supporting all of us,” I said. “I think I can manage one small boy and a cat.”

“You’re nothing without us,” Elaine said, and it was almost pity I felt then. Almost. But not quite.

I went to bed with a notepad and a pen and wrote down my life in a list: job, child, documents, apartment listings, lawyer, daycare. I slept through the night for the first time in months.

The Monday we filed, the house met the news with performative grief and real strategy. “Why don’t we forget all this nasty business,” Elaine said, leaning against the counter like a woman who had never ordered someone else to scrub a toilet mid-meal in her life. “We’re family.”

“Family doesn’t treat each other like this,” I said. “Family doesn’t use the word ‘useless’ like a dog whistle every time it wants breakfast.”

“You’ll regret this,” Alex said. “You can’t survive without me.”

I considered the words. They didn’t fit anywhere anymore. “Watch me,” I said, and turned back to the sink, because what is more powerful than refusing to let someone hold your attention any longer?

“Mom,” Eli whispered that night, his voice small and serious in the dark, “are we going to be okay?”

“We’re going to be wonderful,” I whispered back. “We’re going to be free.” And I meant it.

Part Two

The courtroom was beige. Beige carpet, beige walls, beige chairs that made even rage feel polite. We sat on opposite sides: the Whitmore duo—polish and piety—and me, with Sana beside me and a stack of copies so thick it looked like a pamphlet for a new country.

Alex’s lawyer started with a story: devoted husband, struggling family man, toxic daughter-in-law. It was a good story. I almost wished it were true. It would have made my life easier to explain. Mrs. Whitmore’s performance could have earned nominations. She dabbed at her eyes with a tissue that never once had to work for a living. “All I ever wanted was to be helpful,” she said, eyes streaming words and not tears. “But she… she was always so cruel to me.” Her voice cracked on “cruel” the way a carefully set stage crackles when someone kicks it too hard.

When it was my turn, the room shrank to my voice and the sound of paper sliding across a table.

“I have been the primary earner for this household for three years,” I said. “I paid the mortgage. I paid the utilities. I buy the groceries. I have emails requesting that basic repairs be done and receipts showing that I did them myself when there was no response. I have a recording in which Mrs. Whitmore orders me to clean the toilet while we are eating dinner—a small example of a daily barrage of orders designed not to maintain a home but to assert dominance. I have the transcript of my husband referring to me as a ‘useless wife’ while I paid the bill on my phone.”

“Objection,” Alex’s lawyer said without conviction.

“Overruled,” the judge said, and his voice sounded like maybe it had known a mother-in-law once.

I slid text messages across the table—Alex’s lack of apologies in black and white, Elaine’s insults in full color. I slid bank statements. I slid daycare invoices. I slid screenshots of calendar overlaps that suggested “business trip” and “girls’ weekend” did a little more than overlap.

“Support,” I said, looking at Alex, “is more than saying ‘give me mayo’ with please attached. It is action. And your actions have made a mother out of only one of us.”

Sana saved her coup for last. She clicked the screen alive. The first photo was just enough to make a man lean forward. The second was enough to make him lean back. Photographs. Hotel records. The handwriting of two people who thought discretion was a luxury and not a requirement. Alex’s affair sketched itself in the air like a courtroom sketch artist with a bad attitude and a good memory.

There were murmurs. Some of them were sympathy. Some of them were satisfaction. Mrs. Whitmore inhaled like a woman who has just realized the camera has not always been her friend. Sana did not make the judge wait long to learn the second half.

“Your Honor,” she said mildly, “we will be entering into evidence copies of correspondence between Mrs. Whitmore and Mr. Harwood.”

“Who is Mr. Harwood?” the judge asked.

“Our neighbor,” I said, because if the truth is going to jump, you might as well bend your knees.

Photos. More emails. Mrs. Whitmore’s elegant signature next to an apology about how “last night was too close—my daughter-in-law nearly caught us.” A shot of them leaving a hotel so a second camera could pick them up from a different angle. There are a dozen small humiliations in an affair, but the one in a courtroom that belongs to a woman who called you useless while she used your house as a set for her hypocrisy has a special flavor.

“You invaded our privacy,” Mrs. Whitmore hissed across the aisle, her actress’s mask finally slipping. “You vile little—”

“No,” I said. “I exposed the truth.”

The judge called for order. Then he delivered a verdict so clean it made Mrs. Whitmore sway.

Sole custody. Fair division of assets. A clearly defined support structure based not on the fantasy they’d tried to sell of his competence, but the reality of mine. The judge looked at me and said, “You’ve been carrying it. You may put it down.”

Outside, Eli ran to me in two giant four-year-old steps, his face freckled with concentration. “We did it, Mom,” he said, and it was not triumph in his voice. It was relief. It was space making itself in his lungs.

“Yes,” I said, bending to him, breathing him in like the only sky that matters. “We did.”

News travels. Alex and Mrs. Whitmore had built their lives out of the things people say when they want to impress other people, and now those same people said other things in different voices. The coffee shop buzzed with harmless gossip and careful suggestions. My father looked at me like a man who had always known I was capable of this and allowed me to arrive there on my own.

One afternoon, Mrs. Harwood—who used to drop off pecan pies and pick up town secrets—walked into the coffee shop with her hand gripping the strap of her purse like a lifeline. “I heard,” she said. “All of it.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, meaning not apology but empathy.

“I filed,” she said. “He’s out. And I’m suing her for alienation of affection.” She said it like someone taking back a sentence halfway through finishing it.

“Good,” I said. “I’m proud of you.”

I bumped into Alex on Main two weeks later. He was a reduced version of himself—smaller, not for lack of food, but for lack of swagger. “Amelia,” he said, and the word came out with effort. “Can we—”

“There’s nothing to talk about,” I said. Not out of cruelty. Out of mercy—for him, for me.

“I’m sorry,” he said, and in the pause between the two words there was a hiss of truth. “I depended on you. I… I didn’t see it.”

“You didn’t want to see it,” I said, and then set down the stone I had been carrying since the night of the tea.

The worst encounter came at the grocery store. I was choosing tomatoes and thinking about basil when I felt a presence and the temperature shifted like a door had been opened.

“You did this to me,” Mrs. Whitmore breathed as she passed, not pausing, not looking up.

“No,” I said, picking up the basil. “You did this to yourself.”

I did not feel triumphant. I did not feel vindicated. I felt like a woman who had finally completed a job that had been on her list for five years, and was ready to cross it off and write: Find joy. Learn to rest. Teach Eli to make pancakes that actually flip.

There is a particular kind of peace that belongs to a kitchen no longer policed. I moved us into a small apartment above the coffee shop—two bedrooms, tall windows, a kitchen whose cabinets closed without argument. In the mornings, I would carry Eli downstairs in his pajamas and let him sit on the counter and stir batter while I tried—and failed—not to put too many chocolate chips in. He would lick the spoon when he thought I wasn’t looking and then we would laugh because he has never done anything in his life he wasn’t willing to do twice.

On Saturdays, we would go to the park and feed stale bread to the ducks and he would ask big questions the way only children can ask them.

“Why did Grandma not be nice?” he asked once, head tilted, eyes earnest.

“Some people don’t know how to love the right way,” I said. “So we teach them by loving them from far away.”

He nodded gravely, as if I had handed him a new word. In a way, I had.

Months passed and the noise finally dropped to a hum. The coffee shop flourished—Sana started sending her interns in for caffeine and perspective; Mrs. Harwood hosted knitting nights that were more like community therapy; my father experimented with cardamom in the cinnamon rolls and discovered happiness is a spice blend.

On a midwinter night, I turned the key in the coffee shop’s lock and reached for Eli’s hand. He looked up at the sky, which was performing its soft orange-to-pink trick above the shopfronts.

“Look, Mama,” he said, delighted, “the sky is brushing its teeth.”

“It is,” I said, laughing. “It’s getting ready for bed.”

We walked home slow. The cold made our breath look like ghosts and then like dragons and then like smoke signals. Above us, the streetlights came on one by one, unafraid.

At our door, I paused. I thought of the night I pressed my palm on the cool divorce papers to slide them across to a man who believed my opinion didn’t matter. I thought of the morning a woman told me to clean a toilet while we were eating. I thought of all the small resistances it takes to build one large life.

“You ready for spaghetti night?” I asked Eli.

“With meatballs,” he said, as if we were negotiating international peace.

“With meatballs,” I promised.

We went inside. The door shut. The lock clicked. The world made its gentle sounds—the rinse of water in the sink, the hum of the fridge, the whisper of a boy’s feet skittering over tile.

This is how it ends, I thought—not with a dramatic last word shouted in a courtroom, not with a neighbor’s scandal. With a woman who has decided to stop living in rooms where she is invisible. With a child who knows what peace sounds like. With a kitchen that belongs to only our hands.

Justice had looked like a gavel. Liberation looked like basil and tomatoes. Revenge—if it could be called that at all—looked like living well. And at the table, as Eli stabbed at a meatball with the ferocity of a four-year-old, I raised my glass to the future and drank.

END!

News

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house. CH2

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house Part One “Did you really think…

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: ‘Move in with My Parents or Divorce!’. CH2

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: “Move in with My Parents or Divorce!” Part One The…

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything. CH2

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything Part One The worst…

My Daughter Called Me a Lazy Stay-at-Home Mom, So I Revealed My Secret Business Empire. CH2

My Daughter Called Me a Lazy Stay-at-Home Mom, So I Revealed My Secret Business Empire Part One I never planned…

Fiancé Stolen by My Sister—But I Was the One Smiling. CH2

Fiancé Stolen by My Sister—But I Was the One Smiling Part One The day my sister told me she was…

As he swung his belt, our daughter stood firm: “No more hurting mommy!”. CH2

As he swung his belt, our daughter stood firm: “No more hurting mommy!” Part One The first time Nathan hung…

End of content

No more pages to load