My MIL: “Enjoying the evening, dear? A true woman’s joy is in motherhood!”

Part One

The fork slipped from my fingers and pinged against the rim of the plate.

Patricia didn’t flinch. She held her wine glass aloft and smiled the way people smile in magazine ads—wide, fixed, and empty. “To my son, Ethan, and his wife, Jolene, on their third anniversary,” she sang, the chandelier lighting her pearls with a theatrical twinkle. “May your union continue to be blessed.”

The room went obediently quiet. Uncles and cousins and neighbors sat with polite half-smiles as if on cue. The table glowed with polished mahogany, hand-cut crystal, cloth napkins the color of late roses, but I felt the gleam of it all as a glare. I found Ethan’s hand under the table. He squeezed. He didn’t hear the barb.

“Thank you, Mother,” he said, all dimples and good breeding. “We appreciate you hosting this lovely dinner.”

“Yes,” I added, because the script demanded it. “It’s been wonderful.”

Patricia’s eyes stayed on me. “Jolene dear,” she drawled, “you seem a little tense. Is everything quite all right?”

“Of course,” I said, moving a napkin with more care than a napkin demands. “Just enjoying the evening. As any wife would.”

“I certainly hope so.” Her mouth made a sympathetic shape that never reached her eyes. “Raising a family is such a rewarding experience. No woman’s life is truly complete without it.”

Forks stopped halfway to mouths. Under the table, Ethan’s hand was still reassuringly on mine. Above it, the air curdled.

We had been trying for a year. There were ovulation kits in our bathroom drawer, appointments already behind and ahead of us, a body that had become a timetable and a hope and a stranger. We’d kept it private, not because shame had entered the room, but because grief prefers dim light. Patricia had just thrown the blinds open.

“I think we’ve had enough wine for one evening,” I said through a smile, pushing back from the table. I caught Ethan’s eye and tilted my head toward the door. “Shall we be excused?”

He stood, obedient and relieved. “Of course,” he said. “Thank you again for dinner, Mother.”

We said our polite goodbyes, got into the car, and did small talk all the way home like two people in a play about not-saying.

Twenty minutes later, in the safe ugliness of our apartment kitchen—linoleum with a scrape from an appliance delivery, a magnet shaped like a banana on the fridge—I turned on him.

“Did you really not hear her?” I asked, voice steadier than I expected from rage. “She implied I’m failing as a woman because we haven’t gotten pregnant yet. She applauded our marriage with one hand and slapped me with the other.”

He sighed and hung his suit jacket on a chair he knew didn’t like the weight of jackets. “You know how she can be. She’s… dramatic.”

“Dramatic?” I laughed and didn’t recognize the sound. “She has repeatedly insulted me, implied I’m defective, and tonight chose to do it in front of thirty-seven people and a chandelier. Dramatic is fainting in a parking lot. This is cruelty.”

He lifted his hands in the universal gesture of men caught between the woman they love and the woman who taught them their last name. “Maybe her choice of words wasn’t the best,” he conceded. “But you know how important family is to her. She’s old-fashioned.”

“Old-fashioned,” I repeated, tasting the euphemism. “Like polio.”

He gave me the look he gives students who write things in emails they will regret. “Jolene—”

“Ethan,” I said. “I won’t let her decide what the women in this family are for.” I meant it quietly. I meant it like weather.

He kissed my forehead and went to draw a bath. He had always been good at immediate comforts. I had to become good at something else.

Patricia arrived without warning the next day, arms full of options. “At your age,” she trilled, dropping onto our couch as if it were hers, “you can’t be too careful about these things. I’ve spoken to my gynecologist. He’s the best in the state. His secretary will pencil you in.”

“We have a doctor,” I said, putting the kettle on because boiling water makes fights feel civilized. “We’re exploring our options.”

“Exploring,” she tutted. “My dear, you’re not hiking. This is the future of our family’s legacy.”

She opened a wicker basket lined with tissue paper as if she were releasing doves. Out came baby clothes in frills and shades of sugar: dresses with bows the size of Finn’s forearm, onesies embroidered with ducks, stuffed animals soft enough to bruise.

“Patricia, this is too much,” I said, and meant too much to bear. “You didn’t have to—”

“What did you expect us to do?” She smiled with tiny teeth. “Wait until you finally manage? Lord knows how long that could take at this rate.”

The barb found its wound with professional accuracy. I inhaled a gallon of steam from the kettle and willed myself into silence.

Ethan came home from work with his tie askew and a face that believed the day had ended. “Mother!” he said, delighted. “What a surprise. You shouldn’t have.”

“Nonsense, pumpkin,” she said, all softness with him. “A grandmother must take matters into her own hands.”

Later, in bed, I finally asked what had been clawing the inside of my mouth all night. “Are you really okay with how she treats me? With… this?” I waved a hand in the direction of the house at large, so many rooms still vibrating from her voice.

He froze with his shirt half off, a tableau of good intentions gone wrong. “She has a flair for the dramatic, yes, but she means well.”

“Means well?” I said. “No, Ethan. She wields well-meaning like a club.”

“Enough, Jolene.” His voice slapped the air. I looked at him, not at the man I loved, but at the boy who had been taught to clean up his mother’s messes rather than tell her to stop making them. “She is my mother. I won’t have you disrespect her.”

Something settled in me. It was heavy and had edges. “She’s been disrespecting me since the moment you put this ring on my finger. If you won’t make her stop, I will.”

He stared, speechless. I slept the sleep of women who are past the point of asking nicely.

Clarissa—and yes, I noticed that I had begun calling her by her name—upped her game.

At a Blackwood family dinner at the country club, in a room so large it made everyone smaller, she lifted her glass with ceremony and her voice with malice. “We’ve all been waiting so patiently,” she said, syrup pooling in her syllables, “for the joyous news that the next generation will finally arrive to carry on our proud family name.”

Silence pooled. She pouted. “Alas,” she sighed. “It seems some are simply unable to do their womanly duty.”

Chairs scraped loud enough to make the manager glance up. Someone gasped in delight for gossip and a few in shame for me.

“Mother,” Ethan said loudly and too late. “That’s enough.”

I stood. My mouth said, “Excuse me,” because that is what polite women say when they are leaving rooms that have just set them on fire.

I locked myself in a bathroom large enough to be rented as an apartment in our neighborhood and pressed my hands to the cool marble. How could she bring our grief—the thing we had held carefully and privately—into a room with people who would use it as salad conversation later? For how long would Ethan label her cruelty eccentricity? How long could I survive inside her “good intentions”?

When I walked back in, most people had read the room and left. Patricia had not learned how to read; it is rare she needs to. “There you are, dear,” she said, eyes glittering, voice a knife wrapped in gauze. “We were worried sick about you.”

“Enough,” I said. Patricia flinched. Ethan’s mouth opened. I closed it with a look. “I have swallowed your contempt for me too long, Patricia. And I will not do it again.”

She blinked. Recovering, she rose theatrically. “What on earth could you possibly—”

“This is your last warning,” I said evenly. “I will not be humiliated in public again. If you try, you will regret it.”

I walked out into the very rude gold-paned dusk. My hands shook all the way home. By the time I got there, they were steady again. I called my best friend.

“You can’t let her get away with this,” Rachel said, outrage sharp and loyal on my behalf. “If Ethan won’t intervene, you have to. You have to make it clear she cannot keep doing this without consequences.”

“What if I burn everything down,” I asked, because there is always collateral, always ember-scorched edges that never smooth out.

She didn’t hesitate. “Some houses are better rebuilt.”

Part Two

That night I did a bad thing for a good reason. I combed through old emails for the insults that looked innocuous to people outside the marriage but had been bruises inside it. I slid my phone into a clutch at dinners with her and hit record, capturing the way she shaded her cruelty as motherly concern. I found accusers eager to testify in whisper if not in court: a nanny fired for refusing to force-feed a toddler, a housekeeper who had been told to retrieve “evidence” from our bathroom trash. I met, carefully and in secret, with Patricia’s sister, Sarah, who had endured decades of cruelty less gilded because they were within the family. She handed me a folded piece of paper she had scooped from a therapist’s trash. I read the sentence four times: Difficulty empathizing with others; persistent need to control. It looked like a weather report anyone who had known Patricia could write.

I knew I was trespassing. I did it anyway.

Maya—Ethan’s cousin—came with me the afternoon we set up the audio. “Now?” she mouthed across the table at the gala when the emcee announced Patricia’s closing remarks, plasma screens behind him pulsing with the Blackwood family crest.

“Now,” I mouthed back, and tapped the app.

“…that ungrateful freeloader needs to get off her ass for once and earn her keep around here,” Patricia’s voice snarled—to the room, to herself (how often had she muttered it in our kitchen?)—not over my shoulder as usual but from the ceiling.

Heads snapped up. A hundred pearls clutched their chests. Patricia froze on stage, her smile shattering, her hand tightening on the mic like it might become a sword.

“If she can’t get pregnant soon, she’s out on the street,” came the next clip, my face displayed ten-feet tall behind her, and then Maya’s—Patricia’s insult red-lined into the air, the day she had commented on her post-partum body now made public.

People gasped the way they do at movies when the monster finally appears and isn’t as glamorous as they expected.

A string of Patricia’s own therapy highlights followed—opinions she had thought private now sprawled across screens in a font that felt like indictment: Loathing of weakness. Contempt for those “beneath” her. Belief that she is the only one fit to decide family matters. Patricia screamed “No” into a room that had stopped being hers. Sarah threw her wine in her face with a casualness that looked like years relieved.

By the time security cut the sound and the hotel turned on the ugly lights and tried to herd moneyed people into taxis, the deed was not only done, it was memorized. The country club revoked her membership by brunch. Patrons pulled out of charity boards on which she had performed generosity. Atlanta’s elites had their new obsession; we had our quiet.

“Do you feel better?” Ethan asked, after the smoke, after our fight, after his father’s threats, after people had moved from shock to fascination to avoidance—the way they always do.

“No,” I said, honest as the floor. “But I feel free.”

He came to my apartment weeks later, the old defeat still smudged on him and something else under it—new, raw, unpracticed. “I should have stopped her a long time ago,” he said without preamble. “I should have said something the first time she called you—not your name.” He looked at me, and for the first time I recognized a man who had seen the infection and understood the cure would burn. “If I fight now, will you let me?”

“We don’t know if there’s an ‘us’ to fight for,” I said, because that needed saying and because my anger had to be given a chair and a plate if we were going to eat in the same room again. “But if there is, you will fight beside me. You will not hand me the sword and point me at your mother. You will stand with me with both hands on the hilt.”

He nodded, and I watched him mean it.

We did not return to the house that smelled like her. We made a new one—the kind of home that measures success in minor miracles. In the mornings, Ethan learned to make coffee without apology. In the afternoons, he called Finn and asked about drawings no one criticized. At night, when memories came in like mice, we set traps together—the humane kind that carry things outside.

We met with a counselor who said less than most people we had paid to talk and whose silences made us say more. We learned that healing is not victory; it is practice. We learned how to call each other back into rooms without shame. We learned how to hang pictures on nails that do not enter the wall like weapons.

At Thanksgiving, I took Finn to an exhibit downtown. He sat on a bench and drew strangers for an hour without commenting on their flaws. I watched his face soften into something like concentration and thought, We are winning.

Patricia tried to regain her footing. She called newspapers. She threatened lawsuits. She wrote me a letter that began Dearest Jolene and ended with a paragraph in which she didn’t use the word sorry once. I put the letter in the shredder while humming the song my mother hummed when cleaning up after me because messes are what kitchens are for.

When Douglas’s heart went quiet, I wore a dress that wouldn’t make Patricia comment and stood at a podium beside Ethan and said his father was the kind of man who fixed fences for neighbors he did not like and that is the definition of a neighbor. Patricia kept her sunglasses on for the eulogy and removed them for the cameras. We were both behaving. It passed for peace.

Months later, Finn came over for spaghetti. He twirled pasta and then set down his fork and looked at me over a mound of noodles. “I get it now,” he said, not smiling the way he had learned to do for adults but because he had figured out a thing in his own head. “You didn’t just fight her. You fought for us.”

“Always,” I said, because that truth is the only one that matters.

He nodded, satisfied. He picked up his fork. He ate. We talked about paintings and how to tell a teacher you want to do your own thing without making it a fight. We took the trash out. We stacked plates. We slept.

The invitation to the Ladies’ Society’s retreat arrived addressed to Mrs. Ethan Blackwood and thrown away unread. A second arrived addressed to me. I recycled it too, out of caution and habit. Another came from the Blackwood Foundation’s interim director, not asking for a donation this year but offering condolences. I sent a check to the art scholarship fund with “for people who cannot afford to wait for permission” in the memo line and then went to school early and put butcher paper on the tables because mess is what art is for.

On our fourth anniversary, Ethan and I sat in the park with a paper bag full of apple slices and watched a child build a fort out of leaves and pride. “I’m sorry,” he said again, this time not for the past but for all the futures in which I hadn’t been able to rest. “I know you aren’t a mother yet. I also know motherhood is not the only way to be a woman.”

“Thank you,” I said, because it was simple and sufficient.

“And I know,” he added, looking at the leaves and the light on them, “my mother’s joy is her business. Not yours.”

We threw apple cores to squirrels who ran with them into holes. We walked home. We made a sauce that took two hours and did not argue about the garlic. We called Finn and said, “Come eat,” and when he arrived, he rolled his eyes and then stepped into my hug anyway, and I could feel the angle of his shoulder as a place where something had been set down.

The night was ordinary. I went to bed without rehearsing anything. The house was quiet. If Patricia’s voice tried to enter it, we didn’t hear. We had made too much room for ourselves.

END!

News

I heard my husband and his son plotting against me: “Make sure the poison is untraceable”. CH2

I Heard My Husband and His Son Plotting Against Me: “Make Sure the Poison Is Untraceable” Part One I…

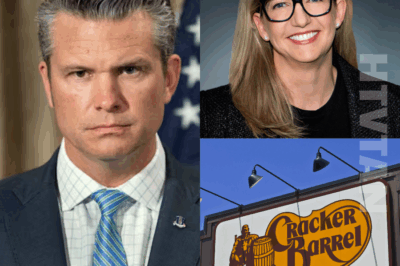

Fox’s Pete Hegseth Mocks Julie Felss Masino, Says Cracker Barrel’s Logo Change ‘Killed Tradition’ — Sparks Fierce Debate Over ‘Woke Branding’. CH2

On live television, Fox News host Pete Hegseth took a direct swipe at CEO Julie Felss Masino, claiming Cracker Barrel’s…

My sister betrayed me with my boyfriend, claiming “He deserves better than you!” CH2

My Sister Betrayed Me With My Boyfriend, Claiming “He Deserves Better Than You!” Part One You think you can…

I snuck into my son-in-law’s house to teach them a lesson, but what i left behind… CH2

I snuck into my son-in-law’s house to teach them a lesson, but what I left behind… Part One I didn’t…

CAN YOU BELIEVE IT? Before Becoming One of Fox News’ Hottest Anchors, Emily Compagno Lived a Double Life! CH2

Before making a name for herself as one of Fox News’ most recognizable faces, Emily Compagno was leading an incredible…

My mother-in-law announced she’s moving in: “It’s decided, dear, no fuss needed!”. CH2

My mother-in-law announced she’s moving in: “It’s decided, dear, no fuss needed!” Part One The fork slipped from my hand…

End of content

No more pages to load