My In-Laws Invaded My Dream Home — So I Arranged A Special Delivery That Made Them Permanent…

Part One

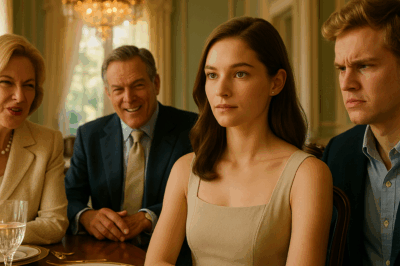

The two suitcases were the kind you buy when you’ve decided the laws of physics don’t apply to you—hard-sided, glossy, rolling quietly enough to seem polite while swallowing a lifetime. They squatted in our foyer like newel posts, their edges nearly flush with the bench I had hunted down at the antique market and refinished myself, one varnished Sunday at a time. Glenn’s booming sports commentary shook the glass in the transoms, and there was my mother-in-law Sandra in my kitchen wearing my apron and the smile she saved for people she intended to steamroll.

“Hope you don’t mind,” she said, as if the sentence were a formality and not theater. “We thought we’d stay a few nights. Glenn’s back is acting up again, and it’s just easier not to drive back and forth.”

Behind her, a pot on my stove was steaming fragrantly. I would discover later she had boiled the good wooden spoon because she thought it “looked dusty.”

“A few nights,” I repeated. It came out bright, too bright, as if my vocal cords had chosen a register reserved for small talk and Christmas lights. The grocery bag cut crescents into my palm. I put the bag down on the bench because that’s what the bench was there for, and this was my house, and people who belong in their own lives set down their bags.

“Nolan said it was totally fine,” she added, and handed me my own colander.

My name is Olivia. I’m 34 and a UX designer, which means I spend my working hours listening to people say how they want to do a thing, watching how they actually do a thing, and designing for the truth. It turns out the same muscles work at home. The truth was this: I had spent three years designing a life I could breathe in, picking tile like punctuation and light fixtures that made morning look like a held note. I had picked an extra room for yoga and meditation that Sandra called “that empty space” until she decided her “scrapbooking projects” needed a flat surface.

In the beginning, I told myself it was lovely that they wanted to see our house. That it was love that made them arrive every Sunday with a pie and a pile of critiques disguised as contribution. “Oh, you prefer fresh garlic?” she would say breezily, as if she were commenting on the weather and not setting up a cross-examination. “We always used powder. It’s so… consistent.” Glenn would skip past my Spotify playlist to land on The Game no one else in the room was watching, then ask me to turn it up because “the commentators mumble these days.”

If I lined that year up now end to end, it would look like a series of very small, very polite concessions. The first time they “napped” in the guest room, leaving the duvet at an angle that made my eye twitch. The second time Nolan called up the stairs to ask why I was “making a thing” about a pile of Sandra’s trial-sized shampoos lined up on my windowsill like a parade. The third time I went to Target on a Sunday night and bought a set of towels I knew I would keep in a cupboard marked GUESTS because I’d cracked the door open and kept my spine straight like a railing and still walked into the room to find Sandra drying her hair with the towel my grandmother had embroidered my name on when I turned thirteen.

The first time I tried to say so, it was a Wednesday, which is a terrible day to demand a change because you don’t have the armor of the weekend and you do have the fatigue of the middle. We were side by side at the kitchen island, chopping bell peppers for fajitas. Nolan measured sour cream into one of our wedding bowls and said without looking up, “They’re just… easy, Liv. You know? Low-maintenance.”

“Easy for you,” I said, because UX had taught me to say the true thing in as few clicks as possible. “Not easy when you’re the one cooking and performing and having your knife technique evaluated.”

He laughed. “They mean well. Come on, you’re overthinking it.”

I overthink by training and by temperament. It keeps planes in the air and interfaces from breaking and marriages from slipping into assumptions. I wanted to say all of that. I wanted to say: It is overthinking that made our tile layout perfect, that kept me from sending our blueprint to the wrong inspector, that means your clients keep telling their friends your firm made their dream house a house they could actually live in. I wanted to say: Overthinking is the love language of people who may not be allowed any other. Instead, I sliced bell peppers with even strokes and said “Okay,” because—God help me—some part of me still believed that if I bent just one more time, the people standing on me might notice they were standing on a person.

So I bent. When they showed up at the door with a pie and then with three meals they would “store in our freezer for convenience,” and then with a list of errands they “just couldn’t get to,” I cleared shelf space and calendar space and the space in my head that separates your thoughts from the soundtrack of other people’s needs. When they began to use our guest room “so Glenn’s back can rest” and their voices trickled under our bedroom door late at night like radio static, I smiled so hard my molars ached. When Glenn opened our office door without knocking to ask where the HDMI cable was while I was on a call with a client who pays for prototypes like people used to pay for diamonds, I said, “Bottom left drawer,” and hung up my mouth afterward like a picture I wasn’t sure I liked anymore.

The suitcases were the line drawn with wheels on. Sandra in my robe was the Post-it note stuck on my life that said: you failed to set a boundary. This was not a breach. It was an outcome.

“Nolan said it was totally fine,” Sandra had said, and the thing was: I believed her. If you don’t design the experience you want, someone else will design it for you.

That night, in the dark, with Glenn’s laughter seeping through drywall, I turned over, took my phone from the nightstand, and texted Rebecca.

Do you still have that guest room?

Her reply came back like a lifeline tossed from a friend who keeps rope by the back door. Always. Bring wine. Bring nothing. Just bring yourself.

I did not run. I did not pack a suitcase as large as my offense. I did not slam a door. The next morning I made Nolan’s coffee exactly the way he liked it—extra hot, splash of oat, pinch of cinnamon because he read one article about antioxidants in 2018 and decided cinnamon was his personality—and left it on the counter beside a small envelope that said only, Nolan.

Inside was one note, handwritten because permanence had begun to feel like a thing I could not find on a screen. I’m going to check on my aunt in Portland. She fell and broke her wrist. I’ll be gone a few days. If you need space, now you have it.

I packed a backpack and my laptop and my grandmother’s embroidered towel because Sandra had announced she was “helping with the wash” and I didn’t honestly trust her not to decide “grandma craft” would be better in the rag basket. I kissed Nolan’s cheek, and he said without looking up from his phone, “Drive safe, babe.”

Rebecca’s guest room smelled like laundry and eucalyptus and the kind of quiet you only recognize if yours has been taken. We ate pasta too late and sat on her balcony with our bare feet on cold metal and talked about redesigning a life the way you redesign a product: identify the pain points, find the pattern of failure, prototype boundaries.

“Make it complicated,” she said when I offered all the reasons I should probably go back and be reasonable. “You’ve been the one simplifying everything for everyone for a year. Complexity is justice.”

“End users don’t like complexity,” I said. Suddenly we were both laughing so hard my eyes watered. “I’m not the product manager of my marriage,” I added when I could breathe. “I’m a person.”

“Then stop scoping this like a feature and treat it like a launch,” she said. “Plan for user adoption. Set the metrics you care about. And for the love of all that is ergonomic, do not let them A/B test your spine.”

This is the thing about good friends: they will turn your own metaphors against you for your own good.

She had an idea that made me put down my wine and pull out my laptop. It involved her brother, who owned a moving company that prided itself on white-glove delivery and the sort of discretion that keeps people in old houses from having to learn new street names. It involved, too, the land laws that quietly shape our lives: who is on the title and who is not, who can sign for a repair and who has to ask, who gets to choose the setting of a story. Nolan’s firm had argued, when we closed, that it would be “simpler” if the mortgage were joint and the deed were not. Simpler, in that specific mouth, had meant traditional. Traditional had meant: power that looks a lot like old furniture.

“We’re going to do a special delivery,” Rebecca said, voice low like plotting in a spy movie. “We’re going to help them move in.”

“Into what?” I asked.

“Into your life,” she said sweetly. “On paper.”

“Be serious.”

“I am.” She put her finger on my list of pain points and tapped the one called uninvited residency. “They are squatting in your space. You need to formalize it on your terms and then make the terms impossible.”

“What does that even mean?”

“It means we deliver them what they think they want and configure it so they have to take it somewhere else.”

I looked at her and saw, in her eyes, the woman who had talked a landlord into replacing the entire complex’s plumbing by finding the code that said they had to if the water failed for more than 24 hours. I looked at my phone and saw a text from Nolan that said, We’re thinking we’ll have them stay through the weekend. Easier than packing twice. When I looked up, my decision had a shape.

The next morning, I called Rebecca’s brother, and he started laughing before I finished the sentence. “Oh, I’ve done this one,” he said when I told him the front-end story. “Not with in-laws. With a band’s sound guy. He woke up in Fresno.”

“Please do not kidnap my in-laws,” I said. “Also, don’t let them know it’s from me.”

“I’m a professional,” he said, which was inarguably true.

We set a date for the special delivery, which is a thing his company actually offers: move-in services for senior clients where the movers unpack, plug in lamps, hang the good mirror, and put the slippers beside the right side of the bed. We set a second date two days later that would involve me and a lawyer and a notary and a phrase I had never thought I would use in my marriage: separation agreement.

The last piece required a house. Not mine. Not theirs. Somewhere between an apology and a boundary. It turns out Charleston has a whole market of small houses that dream of being bigger and could settle for being enough. When you’ve spent a year with people explaining why a thing that only affects you should be their decision, buying a house in an afternoon feels like therapy.

I found a two-bedroom on a street fifteen minutes away from us that had a screened porch and a yard crying out for a bench. It smelled like mildew and old decisions. It had good bones; you could tell by the way the hallway light hit the baseboards. The owner was a nurse moving to be closer to her daughter in Asheville. She liked that I liked the metal mailbox that still said HELMS in stick-on letters. She liked that I said porch like a person who knew the difference between sit and linger. We closed in ten days because I had a down payment and a reason, and lenders love a reason with bullet points and a UX designer’s signature, neat and even.

While Nolan ate brunches and Glenn used my den like a sports bar and Sandra arranged my spices by her astrological chart, Rebecca and I arranged the rest: utilities started, a cleaning crew, a handyman to fix the leak under the sink and hang a grab bar in the shower, a neighbor named Miss Ruth who agreed to be the person who knocked if a trash can stayed at the curb too long. I bought a mattress that felt like a hug and towels that would not carry anyone’s history. I bought spices and put labels on them that said Basil and not BASIL. I called a company that installs small ramps and white-glove delivered one to the back step.

We scheduled the moving truck for 9 a.m. on a Thursday because people are their least theatrical in the morning. Rebecca’s brother printed a work order that said in bold letters: MOVE-IN DELIVERY: GLENN & SANDRA RADFORD — NEW RESIDENCE, 912 SILVER HILL LANE. He put a sticker on each box that said RADFORD — MASTER BEDROOM and RADFORD — KITCHEN and RADFORD — DEN. People do what paper tells them they are. We just made the paper tell the truth we needed.

I left Nolan the envelope that night. I kissed his cheek and whispered, “I’ve missed you,” because I had, even if the man I missed was from ten months ago. He turned his face toward mine and said, “You smell like peppermint,” because he is a builder and notices finishes. I drove to Rebecca’s and slept like a person whose house had stopped talking in a stranger’s voice.

At 9:06 a.m. Sandra opened my front door with my apron on and said, “Can I help you?”

“Move-in delivery,” the lead mover said, cheerfully professional. “Radford, right?”

“Yes,” she chirped, because the story that calls you queen is easier to agree with than the one that calls you guest.

They brought in two boxes of kitchen things from a house I had, frankly, never seen them use properly. They carried up a recliner that matched nothing but Glenn. They placed a box on my yoga mat that said CRAFTS and had a glitter glue leak blossoming through the cardboard like shame. Then the lead mover consulted his manifest and said, “Ma’am, this way,” and escorted Sandra to his truck like a royal procession, down the walk, past the bench I had found in a store that also sells antique doorknobs, to the curb where a second truck idled.

Glenn shuffled out in slippers and asked, loudly, “They deliver recliners now?”

“They deliver everything now,” the mover said. He smiled, and Sandra smiled back because she likes a world where she is catered to. He offered her the passenger seat. “It’s a white-glove day,” he said. “You’re not lifting a thing.”

“Where are we going?” she asked, finally.

“To your new residence, ma’am,” he said, and if he kept his voice gentle, it was because he is a better actor than most in-laws.

I would hear later that Glenn got in without an argument because he fully believed the entire world was arranged for his convenience. That Nolan came home at noon to find the couch gone and the television unplugged and a note on the counter that said: Special delivery — please call dispatch if you have any questions. That Sandra called him from the porch of 912 Silver Hill Lane in tears and joy and confusion because the movers had literally put her slippers by the bed and that made it real. That Glenn slept that night in the recliner with the remote clipped to a lanyard the way his doctor had told him to do months ago.

I did not answer Nolan’s first call. Or the second. On the third, I picked up and said, “Hi.”

“What did you do?” he asked, not even trying for hello.

“I executed a move-in,” I said, and then waited because silence makes people fill in the blank with the thing they don’t want to say.

“You moved my parents into a— into a— is that a duplex? What is this?”

“It’s a two-bedroom half a mile from a grocery store and three doors down from Miss Ruth, who will be your mother’s friend within a week,” I said. “It’s a house. It is theirs while they act like adults. It’s not lashed to my living room.”

“You can’t just—”

“I can,” I said. “I did. And Nolan—” I chose my words like you choose tile you will see every day for a decade. “The movers were white-glove. Everything labeled. They are comfortable. Your mother can bake her terrible casseroles without using my grandmother’s towel. And you can come home to our house and hear yourself think.”

There was a long pause, the kind you can walk around in. “It’s… nice,” he said finally, as if the concession cost him a rib. “They said it’s nice.”

“They will thrive there,” I said. “Or they won’t. Either way, not in my foyer.”

That night I emailed him the separation agreement. The subject line was one word: Boundary. A UX designer knows the value of affordances. This paper made our next action obvious. I had crafted it with a lawyer who reads both code and subtext. It said, in plain language, who paid what and why. It listed the house I had, yes, put my name on alone because Nolan is a man who uses the words “I’ve got you” and thinks that means the land registry doesn’t matter. It said what happens when people don’t choose you. It said what happens when you choose yourself.

He called me the next morning and said, “You’re really doing this over a couple of weekends?”

“It was never a couple of weekends,” I said. “It was Sunday after Sunday after Sunday of being erased in my own house. I am drawing my shape again.”

“You want me to… what? Kick them out?”

“No,” I said. “Handle it.”

He did not. Not immediately. He tried to hold both ends of the rope and then discovered he was the rope. He called me to ask where I kept the vacuum bags and if lasagna could be burned on the inside and still safe. He sent a photo of a grocery cart filled with things his mother always bought and then asked, plaintively, “What do we eat?” He started sleeping on the couch because “your mother snores,” he texted, and then caught himself and wrote, “Despite earplugs.”

For two weeks I let him live in the house he had engineered without me. For two weeks he mowed the lawn alone and answered his parents’ questions and felt the fabric of our couch wear thinner under bodies that were not mine. For two weeks he did not hear me swallow my yes. Then he said the thing I had been rehearsing my answer to since the moment I changed the title on the deed.

“Maybe,” he said carefully, “maybe we should sell the house.”

“That’s up to you,” I said. “If you do, I have right of first refusal.” It was in the paperwork because I had learned the hard way to write down my value before someone tried to grade it on a curve. He did not ask what “first refusal” meant. He hired a realtor who took pictures of my living room with Glenn’s foot massager in the frame and Sandra’s Post-it notes on the spice rack that said “BASIL” and “DO NOT TOUCH.”

The listing went up and down in a month because you can sell even a haunted house fast if you price it ten percent below market. I did not buy it back. I had built a mental shed out back of myself and moved into it, and when you do that, you stop mistaking buildings for shelter.

The day the sale closed, I met Nolan at the coffee shop we had used to meet at when our only fight was whether we had enough in savings to buy nicer knives. He looked like a man who had found his way to the present tense through three rooms of his childhood.

“I’m sorry,” he said first, the way a person does when he has practiced it in front of a mirror.

“For what?” I asked, and made him say the long list so he’d hear it out loud.

“For not listening. For letting them turn our house into theirs. For the way I acted like being comfortable is a right reserved for me. For assuming you’d handle it because you always handle everything.”

“Do you know why I handle everything?” I asked.

“Because you don’t trust me to,” he said, and then winced because he realized he had just told the old story again.

“Because if I don’t, no one else does,” I said. “And because it’s easier than asking again.”

We sat with that. The barista called a name that wasn’t ours. A man in a suit tripped over the door mat and laughed too loudly. The city went on doing what cities do: making twelve kinds of noise and asking people to learn the difference between a siren and a saxophone.

“I signed the separation agreement,” he said finally, and pushed a copy across the table. His signature was neat. Builders have neat signatures because they are markers of responsibility.

I read it in three minutes because I had already read it in the dark when Rebecca slid it across her kitchen table with the gravity of a surgeon. I nodded. It was fair. It said I would keep what I had built. It said he would pay for what he had promised to pay for. It said that if we tried again, it would be with a piece of paper that spelled out how we would behave, not who owned who.

“We can try,” he said, and for the first time in months he did not look at his phone during a sentence. “But not if it means going back.”

“Try what?” I asked.

He swallowed. “Us. With a door nobody else has a key to.”

“You’ll have to tell them the door is closed,” I said.

He nodded. “I already did.”

There was a kindness in the way he said it that made me consider making room again. Then he said, “They’re living in the little house. Glenn wants to build a deck,” and that made me smile in spite of myself, and that was enough for a first step.

We didn’t buy a new house. We rented a townhouse with a balcony that got morning light and a view of a tree the internet can’t name, and that felt correct. We made dinner in a kitchen where we bought the cheapest set of knives as penance and then upgraded to knives that would not punish carrots. The yoga room happened like a recommitment: small, clean, with a mat that did not have glitter on it.

Sandra texted once, months later, a message with an exclamation point that tried to rewrite history. “Coffee?” it said. “Just us girls!” I deleted it because you do not pour coffee into a crack you have finally sealed. Glenn never texted. He mowed the tiny lawn at 912 Silver Hill Lane and waved at Miss Ruth, who told him he was cutting it too short and he did not argue because Miss Ruth’s stare is stronger than mine ever was.

Sometimes, when I pass their street, I slow down and look at the bench I put under the dogwood and feel eleven feelings at once, like a chord that doesn’t resolve. And sometimes I park around the corner and sit on the bench myself and text Rebecca a photo of my shoes on my own feet and she sends back a string of heart emojis as if to say: look what you nailed.

I tell people, now, if they ask and if they seem like they will not weaponize the knowledge, that my special delivery was not punishment. It was a mirror. I ordered white-glove service and gave my in-laws a house of their own because I needed to test whether they were capable of living in it. They were. Which meant what we had been doing in mine had been something else entirely.

The paper made it permanent. The move-in made it real. The boundary made me a person again.

If you’ve read this far, you might be waiting for the moral. My job trained me to think there’s always one, even when you hide it in a modal and hope no one bothers to click Learn more. Here’s mine: You can’t design other people. You can design your life. Sometimes that looks like a gentle delivery at 9 a.m. with boxes labeled by room. Sometimes it looks like a document with a line for a signature and a pen that has good weight in the hand. Sometimes it looks like leaving a house you painted yourself and walking into an apartment with nothing on the walls and breathing for the first time in months and realizing the quiet is not emptiness. It’s space.

It’s yours.

Part Two

The first Sunday without a knock felt like waking up on a school day and remembering summer had started. The silence had a temperature—cool like tile in the morning, kind to bare feet. I made pancakes because I could, because nobody would “helpfully” rearrange the bowls or “accidentally” set the oven to broil and then say ovens are so confusing these days.

I was halfway through stacking strawberries into a smiley face—because I am my grandmother’s granddaughter and we dress food up when life undresses us—when a familiar truck eased against the curb. Nolan got out carrying his toolbox like a passport he wasn’t sure would get him through customs.

“You forgot your coffee mug,” he said, holding up the one that says Design is how it works in Helvetica because our house is that kind of house, or it used to be. He smiled, then let it fall. “Do you have fifteen minutes?”

The thing about two people who have known each other since “oat milk” was a punchline is that you don’t just have fifteen minutes. You have the first day you met and the time the power went out and you played Scrabble by candlelight and the afternoon you both cried on the kitchen floor because the backsplash grout was the wrong shade and it felt like a metaphor. But I nodded and led him to the balcony because our balcony has no ghosts.

“I signed,” he said, and slid his copy of the separation agreement across the little table. He had fixed a crooked outlet in our townhouse on Friday, and the faceplate gleamed like a small apology.

“I know,” I said. “I got the countersign.”

“I went to look at a two-bedroom off Rutledge,” he said, eyes on his hands. “I made an offer on a project in Summerville. I started a spreadsheet of pros and cons of rugs, which I realize is both growth and a cry for help.”

“Nolan.” I said his name like a punctuation mark. “What do you want?”

He took a breath and looked right at me. “I want to do it differently. I will mess up. I will think a boundary is a door I can stand in until you walk around me. I will tell my mother no and then call you and ask you what to do with the silence. But I want to try without asking you to go back.”

My job, when done well, turns desires into flows. “Okay,” I said. “Pilot program. Six weeks. No unscheduled visitors. We share a calendar and a grocery list and a rule: we do not solve problems at midnight. And—this one is non-negotiable—we go to therapy. You solo. Me solo. Then together. Two sessions a month minimum.”

He nodded with the solemnity of a man accepting a building code. “And Sundays?” he asked quietly.

“Not theirs,” I said. “I am reclaiming Sunday. If we feel generous in month three, we can assign them a Wednesday.”

He barked a laugh, surprised. “A Wednesday,” he echoed. “You’re punishing them with the most boring day.”

“I am giving them what they gave me,” I said. “The middle.”

He stayed for pancakes. He washed the plates. He didn’t comment on the strawberries.

You can set a boundary in words without believing it in your body, like how you can tack a sticky note that says Don’t forget carrots and still come home with parsnips and regret. My body needed to learn yes again.

Sandra tried the porch route on day ten. She arrived with a pie and the expression of a woman who imagines herself delivering grace. I opened the door but not the lock.

“Oh, Liv,” she trilled, hands full. “I brought—”

“Please text before dropping by,” I said through the gap, voice level. “We aren’t accepting unscheduled visits.”

“It’s just a pie,” she said, wounded.

“It’s a policy,” I said, and the word surprised even me with how good it felt in my throat.

She squinted, as if trying to read fine print on my face. “You don’t have to be cruel.”

“No,” I said. “I don’t.” Then I texted Nolan and told him his mother had pie on my step. He came and escorted both pie and mother to 912 Silver Hill Lane. Miss Ruth texted me thirty minutes later: Now that’s a nice porch. Pie looked dry. I gave them my whipped cream recipe.

The beauty of a small city is that your life becomes a series of short stories told in grocery store aisles. The cashier who has pierced ears and a degree in sociology told me she’d seen Glenn at the hardware store buying felt pads to put on chair legs “like a gentleman,” and it was the softest sentence I’d heard in months. A week later, Miss Ruth put a folded piece of paper in my hand while we waited out a late spring rain under the awning at Beans & Leaves. It was a copy of a letter, printed on fancy paper and stamped in one corner with an actual seal.

WELCOME HOME PACKAGE — 912 SILVER HILL LANE

The letter wasn’t from me. It was from a trust, which is to say from a mechanism that exists so people can rest. It said, in lawyerly language softened by a paragraph of plain words I insisted on, that the house on Silver Hill Lane was not a staging area. It was a home. It laid out terms: pay the utilities on time (the trust would auto-debit for six months while they got sorted); keep the yard trimmed (the ramp installers had a list of reputable mowers); no extended guests (we defined “extended” like two UX designers: with examples). It also included a grocery card to the small market three blocks away and a maintenance subscription that covered two free handyman visits a year because pride gets loud when the sink starts dripping.

I did not write their names on the deed. I did something better: a life estate. It gives you the dignity of permanence without asking a daughter to fund a monument to her own erasure. If they took care of the house, it would take care of them. If they didn’t, they had the right to complain to Miss Ruth, who does not suffer fools in cul-de-sacs.

The letter arrived in a white-glove envelope, delivered by the same crew that had put their slippers by their bed. Sandra called, breathless, and left a voicemail I did not have to listen to because I already knew what she would say: “You didn’t have to.” Some sentences are a mirror. They reflect what you are not seeing.

Glenn came to the townhouse two days later to fix a cabinet door he’d banged into a wall at 42. He knocked, which is a growth pattern, and handed me a mason jar full of screws like a peace offering. He looked smaller in my doorway, which is another way to say: I had become the correct size in my own life.

“We have our own trash day,” he said, apropos of nothing. “Guy waves at me. It’s a good route.”

“I’m glad,” I said, and I meant it. Then, because theories deserve data: “How’s the ramp?”

“Less tripping,” he said grudgingly, then looked at my kitchen like a man confessing a sin. “I left the TV volume at 28 last night,” he muttered. “Miss Ruth said 30 is for Stanley Cup.”

“Good policy,” I said.

He took out a folded piece of paper from his back pocket and held it out. It was from the hospital. A follow-up. He had actually gone to the appointment his doctor scheduled months ago and came home with instructions he’d read and underlined. This is what happens when you remove an audience. People stop performing and start participating.

Boundaries are boring once you respect them. After the initial drama, life settled into a rhythm that looked suspiciously like the one I had imagined when we were still picking tile. I went to work in a room that had a door nobody opened without knocking. I did yoga in a room that had nothing but my breath and a plant that refused to die. On Tuesday nights, Nolan came over for therapy homework and pasta. Sometimes we ate on my balcony and looked at the tree the internet still could not name and did not try to rename it out loud.

We went to a couples therapist who wore clogs and carried a stack of tissues like a prop she never used. She had us draw our relationship like a floor plan and then put sticky notes that said HISTORY and FAMILY and RESENTMENT on the parts that squeaked when we walked on them. Nolan labeled a wall PRIDE and then wrote under it in smaller letters I thought taking care of my parents meant making you take care of my parents. He cried once, quietly, and then wiped his face with the sleeve of his flannel because clogs-lady would not move the tissues fast enough to save him.

My own therapist and I worked on a different drawing. A blueprint of myself, the doorways I had widened until they were thresholds people camped under. The windows I had thrown open in case someone wanted to come in without ringing. We put in a lock on the back gate and a bell on the front and planted a row of hedges that did not scream defense so much as design. We made a Sunday box in my calendar and put nothing in it on purpose, then watched my body learn how to rest again. The first Sunday I lay on the rug and stared at the ceiling fan and realized it was silent because nobody was stomping down the hall, I cried. Then I laughed, because healing is nonsense and verbs get slippery when you are making a self.

Sandra tried three more times. Once with a text so long my phone made it smaller to fit: Coffee? Just us girls! I miss you. Once with a plié around Nolan, inviting him to her house for “Sunday dinner like old times,” a phrase that made my skin crawl because old times are not always good times; sometimes they are a set you have to break down with a crowbar. Once with a box of “keepsakes” from Nolan’s childhood that contained more of Sandra than of him. I deleted the first without answering. Nolan declined the second and sent a photo of his therapy homework instead. For the last, we dropped the box off at 912 Silver Hill and Miss Ruth texted me later: Put the pictures on a shelf. Told her: looks better there than in somebody else’s living room. She nodded. Mark it down: growth.

On a Tuesday in June, the weather gave us a storm the weatherman tried to name. Rain knocked at our townhouse like a persistent cousin, and just before midnight, my phone buzzed with Miss Ruth’s name.

911? she wrote first, which is how older people use texting to test urgency. Then, Glenn fell. Ambulance on the way. Sandra is… Sandra. Help?

You can detest a dynamic and still show up when a person bleeds. I threw on shoes and a raincoat and beat the ambulance by two minutes. Glenn lay on the floor, grimacing like a man whose body had just remembered how much weight it has to carry. Sandra was walking in circles with a dishcloth, weeping and narrating her weeping.

“It’s not broken,” the EMT said after prodding. “Probably a bad sprain. We’ll take him for X-rays.”

Sandra looked at me over his shoulder, mascara in two clean lines like streetlights in a wet windshield. “I’m not… good at this,” she said in a voice I had never heard from her, small like a child admitting to a stolen candy.

“I know,” I said, and handed her a bottle of water and a paper bag for her “things,” which turned out to be earrings and pride. Then I rode in the front of the ambulance because all those Sundays in my kitchen had taught me where the potholes were.

In the ER at 1:12 a.m., Glenn reached out toward Nolan—who had arrived wild-eyed and soaked—and patted the air like he was trying to find a light switch. “I’m okay,” he muttered. “Tell her to stop crying,” and it would have been funny if it weren’t a whole marriage in a single sentence. Sandra stopped mid-weeping to glare at him, then caught herself and laughed, wet and short. Growth, marked again.

“I appreciate you coming,” she said to me later in that gray corridor air where even the vending machine looks exhausted. “I know I’ve been…”

“Loud,” I supplied. “Rude. Entitled. Cruel.”

She blinked. “I was going to say… not my best self.” Then, quieter, “The way my mother was with me.”

There it was. The blueprint nobody had drawn for her. I nodded. “It stops where you put the wall,” I said.

“Walls,” she said, lip twitching. “You and your walls.”

“Design,” I said, and cracked a smile.

We got Glenn home and settled and I went back to my townhouse in a car that hummed a song I didn’t recognize because my brain was still two blocks behind. I lay in bed and stared at the ceiling and thought about my bench under the dogwood at 912 and how sanded wood can forgive a dent if you run your hand over it enough times.

A week after the ER, an envelope arrived at 912 Silver Hill. Miss Ruth texted me a photo of it because she takes her job as street archivist seriously. Recorder of Deeds — Charleston County. Inside was a copy of the filed life estate. Permanent, with conditions. A thin, serious letter that made something in my ribs unclench because permanence, when selected, is a kindness.

“Why did you do this?” Sandra asked on the phone that night, her voice careful. No trills. No chemical smile. “The ramp. The grocery card. The… everything. After everything.”

“Because I have to live inside myself,” I said. “And I want it to be a place with good light.”

She exhaled. “I don’t know how to say I’m sorry without you thinking I’m manipulating you.”

“Try it on a Wednesday,” I said. “Low stakes. Nobody likes Wednesdays.”

She laughed, a real sound. “Wednesday at two,” she said. “I’ll practice.”

Nolan and I did therapy like people do physical therapy: awkwardly, faithfully, with a lot of sighing and one or two curse words when the stretch hit scar tissue. We built a calendar and put two date nights on it, one no-phones, one yes-phones-because-life-is-what-it-is. He moved into a small apartment with floors that creaked and the humility to not fix them for the first six weeks. He cooked chicken he didn’t call my mother’s chicken and learned how to use my box grater without losing skin.

I kept my townhouse with the balcony and the plant that refused to die. I did yoga in the mornings and cried sometimes when a song I hadn’t remembered I loved came up on Spotify because healing is a long hallway with a dozen doors and some of them lead to memories you have to walk through to get to the kitchen.

In August, we went to 912 for lemonade. It was Miss Ruth’s idea. “Neighborhood watch,” she texted. “I watch. You neighbor.”

Sandra had made cookies that tasted like she’d finally found the right ratio of butter to apology. Glenn kept the TV volume at 24 because “Stanley Cup is the only exception,” and we sat on the porch and watched dragonflies make geometric patterns the way they do when the heat finally breaks. Nolan fixed a loose board on the step. He did not narrate his fixing. Sandra handed me a jar of her homemade pickles without a label that screamed PICKLES, and I took it without thinking about my spice rack.

“I started a book club,” she said out of nowhere. “At the church. We’re reading that one about boundaries. I thought it was going to be about fences,” she added, wry.

“How’s the ramp?” I asked Glenn, because small talk is love when you pick the right topics.

“Stops me from being a dummy,” he said gruffly. Then, after a beat, “I’m sorry, you know. About the… before. I don’t say this right.”

“You’re doing fine,” I said. “Wednesday-level fine.”

We laughed, all of us, and it felt like a rehearsal we might actually perform one day without freezing.

When the sun started to slide toward that version of yellow you can’t order but you try with paint swatches anyway, Nolan squeezed my hand, and Miss Ruth snapped a picture with a phone she claims to hate. It is, to this day, the only photo of me with my in-laws I keep on a surface I dust. Sandra’s hair looks like she stopped fighting it. Glenn’s eyes have a softness I haven’t seen since the first day he walked into our unfinished kitchen and saw the light hit the quartz and said, grudgingly, “You did good.” Nolan’s face looks like a man who learned how to carry something without asking someone else to hold it for him.

I look like a person who made a delivery and got a life.

I would like to tell you we moved back in together, that we took vows in our own living room where the light hits at five, that my yoga room now holds a crib because life made room for a future. That is not what happened. We did not rush the ending. We measured twice and cut once, like grown-ups. Nolan rented across town for a year that felt like three because time plays tricks when you are rebuilding. We dated. We set calendars. We said no, together, when Sandra tried Thanksgiving six weeks early and we said yes, together, to a Friday night movie that involved dragons and a bowl of popcorn big enough to rescue a drowning child.

A year to the day after the moving truck put their slippers by their bed, we stood in front of a deed office and signed papers on a house that was not restorative or aspirational but sober and right. We put both our names on it because there are some lessons you write into law. The house has a porch and two good trees that will fight the wind for us and a laundry room that does not require you to brush past anyone to get to it. It has a room that is mine and a room that is his and a third room we call The Room until life tells us what it wants.

We sent Sandra and Glenn a photo of us sitting on the new porch step, holding a key between two fingers like a ribbon. Sandra replied with a photo of Glenn holding a drill, captioned Volume 22. I wrote back, Good policy.

On the first Sunday in the new house, which is a sentence I no longer fear, I made pancakes again. I set strawberries aside, and when Nolan reached for them, I didn’t slap his hand away like a trope. I let him decorate one, badly, and we laughed and then ate them anyway. The door did not open without knocking. Nobody asked where the HDMI cable was. The air had a temperature I could not name, and that felt like the point.

And the bench under the dogwood at 912? Sometimes I still go. I sit with Miss Ruth and talk about trash day and seasons and how you can tell when a person means it. She brings lemonade. I bring cookies. Sandra walks over sometimes and sits for ten minutes and then plays with her keys and says she has to check the oven. Progress is boring and that is its virtue. Glenn waves from the porch and then goes inside, probably to watch something at an appropriate volume.

“No more special deliveries?” Rebecca asked last week when we boxed up her apartment because she had found a place with windows that look like sentences. I thought about it, and then I shook my head.

“No,” I said. “Unless we order a bench for the back garden.”

“White-glove?” she asked, mischief in her eyes.

“Always,” I said. “It’s how we live now.”

END!

News

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… CH2

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… Part One The pen…

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… CH2

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… Part One The…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… CH2

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… Part One The…

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… CH2

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… Part One The emergency room’s…

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

End of content

No more pages to load