My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings.

Part One

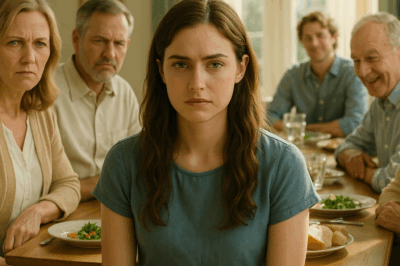

At our reception, my mother-in-law made the toast you’re not supposed to come back from.

She stood beneath a chandelier as wide as a small planet, the crystals turning champagne light into a thousand tiny knives. The band’s pianist actually stopped mid-arpeggio when she clinked her glass, and two hundred of our guests—my engineers in loaner tuxedos, my product lead who arrived late and harried from a production incident, my co-founder Elena with her feral smile—rotated as one to face the woman whose approval I had stopped applying for months ago.

“I’m just so grateful my son found someone to take care of him financially,” Linda said.

It was the tone more than the words. If you know that tone, you know the sting; if you don’t, God bless your lucky bones. She delivered the line with the performative lightness of someone who believes humor is a shield against later accountability. People laughed. People always laugh when they’re not sure if they’re supposed to be offended.

Frank, my father-in-law, lifted his coupe like a gavel. “Here’s to our new daughter-in-law,” he added, grin like a mall Santa who’s done too many shifts. “The lucky gold-digger who hit the jackpot.”

Jason, my brand-new husband, tittered. It was the thin, anxious laugh of a man who wants the nuclear device on the table to be a candle. He put his hand on the small of my back, gentle pressure as if he could pat the humiliation down.

I lifted my own glass and smiled with all my teeth. If they had been the type to notice such things, Linda and Frank might have seen it wasn’t the kind of smile a woman makes when she’s been rescued. It was the expression of someone taking a measurement.

Everyone at table three—my people—had the look of an orchestra about to go on when the lights fail. Elena caught my eye. Not yet, she mouthed. The plan wasn’t ready yet.

Six months earlier, when Jason proposed under paper lanterns on a beach where the tide came in like a round of applause, Linda hugged me and whispered, “You’re lucky, dear. He’s a good provider.” At our engagement party—the one I offered to fully fund on a rooftop with a decent caterer—she canceled my venue deposit while I was still on the call with the florist and moved the whole thing to her church basement with folding chairs and a grocery sheet cake she would later praise herself for “pulling together.” Her particular genius was to frame her control as a gift.

The first dinner with his parents, in their dining room that was the exact color of their social aspirations, went the way such dinners go when men who watch financial news on mute try to understand what a fintech platform is. I said I was building a payment-processing system; Frank waved it away. “Playing with computers,” he said, tender as a slap. “Support his real career.” Jason’s “real career” was a perfectly respectable middle-management job at an insurance firm where ideas went to be embalmed in memos.

I was twenty-nine, my company, Apex, had just closed a round that valued us north of eight figures, and my personal net worth—on paper, at least, as startup wealth always is—would have made their “sophisticated” brokerage statement look like a middle-school checking account. But I didn’t show them any of that because I had already learned the single hard lesson women learn when they are the thunder and the world thinks they should be rain: you don’t convince people you’re a storm by showing them your cloud formation. You convince them by changing the weather.

The night of the toast, Elena waited until Linda had finished performing gratitude and until Jason had stopped vibrating, then drifted over to our table like smoke from a candle that refuses to go out. “They’re still with Sterling?” she asked, low, as if we were discussing a family diagnosis near the hors d’oeuvre table.

I already knew the answer. Two weeks earlier, over pot roast and a bottle of wine they bought on sale, Frank had waved a tidy folder of quarterly statements in front of me like a maître d’ with a reservation book. “Sterling Financial Group,” he said, like a magician revealing the second card you’ve already seen. “Old school. None of this app nonsense.” He offered to “teach” me about real money management, the way men sometimes offer water to women they’ve just watched climb out of a well.

“Two point three million,” Linda had said, with the theatrical interest of someone checking on a soufflé in an oven window. “That’s real money, Megan.”

Real money. Real wealth. Real, real, real. The family used the word as a cudgel and a cologne.

Elena had called me the next morning. “Do you have any feelings about the words hostile and takeover?” she asked, cheerful as a child with a new slingshot.

We met for coffee at our usual hole-in-the-wall, a place with chipped mugs and a barista who called everyone babe and their dogs angels. Elena slid a slim folder across the table. The logo on the front: Sterling Financial Group. Inside: charts like blood pressure dropping, client satisfaction curves like a ski slope, operational costs like a bathtub filling with lukewarm stale bathwater.

“They’re leaking,” Elena said. She has never liked the word hemorrhaging; she thinks it gives cheap drama to something that should be handled with gauze and numbers. “Assets under management down thirty percent in eighteen months. Outdated investment strategies, fee structures you could file under malpractice if you were feeling spicy, and a CIO who still thinks bond ladders are a personality.”

“And my in-laws’ money,” I said, and if you could have measured the temperature of my voice, you would have known it dropped exactly to the degree of my resolve.

“Our money,” Elena corrected gently, tapping a spread that showed what Sterling could be under someone like us. “We buy them through Rodriguez Capital, we plug in Apex’s rails, we give their clients actual performance and transparency for once in their lives, and you get exactly one holiday where nobody calls you a gold-digger.”

The acquisition itself was less a siege than a hospice admission. Sterling’s board had been warming to the idea of surrender since before our engagement party. Elena’s capital gave them a comfortable place to put their shame. Our due diligence gave us the weeds we’d have to pull. The closing papers were the weight of a good coffee table book. I signed my name in a dozen places with the particular pleasure of someone drawing a line and calling it a boundary.

Two weeks after Jason and I said “I do” while Linda watched for fake tears like a bouncer checking IDs, I walked into the Marriott’s grand ballroom and watched his parents divide the room like they were playing Risk and the prize was other people’s admiration. Sterling’s annual client appreciation gala was the exact shade of pomp that fools mistake for permanence. There were soft cheeses with names pronounced incorrectly and a jazz trio faintly annoyed by their own professionalism. Elena arrived with three lawyers whose suits looked expensive in the way bridges look solid: you trust them because they are.

We had coordinated with the event coordinator earlier in the day. “A brief announcement before the performance review,” Elena had said, like a teacher asking to borrow five minutes at the assembly. He nodded quickly, like someone giddy at being backstage for once.

When his voice came over the microphone and asked for the room’s attention “for a small development,” you could feel the oxygen molecules decide they wanted in on the gossip. Elena stepped up to the podium, cool as a winter sunrise. She took five sentences to say what most men say in twenty, and by the time the fifth landed—“as of five o’clock today, Sterling Financial Group has been acquired by Rodriguez Capital Group in partnership with Apex Technology Solutions”—the floor was already moving under people’s feet.

Frank did that thing people do when the cruise ship turns and they have not widened their stance. He grabbed for a nearby chair back and made a noise that sounded like his cholesterol giving way. Linda froze like a deer who has realized the headlights are inside the house.

“I’d like to introduce your new CEO and majority owner,” Elena said, gesture as smooth as power. “Megan Chen.”

I took the steps to the podium slowly for once in my life. I have learned men of Frank’s era only respect two rhythms: thunder and funeral. I chose a measured march that felt like both.

“I want to assure every Sterling client that your accounts are secure,” I began. “We’ll conduct a comprehensive ninety-day review of every portfolio with the aim of aligning strategies to your actual goals and risk tolerance. For many of you, that will mean restructuring. For some of you, that will mean fewer Las Vegas trips disguised as conferences.”

A laugh rose, relieved and nervous. It told me where we could push.

“Effective immediately,” I continued, “any underperforming, mis-aligned, or fee-bloated strategies are frozen pending review. Communication with clients will be respectful, timely, and transparent. That includes family members.”

I didn’t look at Frank when I said it, but you didn’t need to; the room did it for me. Linda grabbed his forearm like she was preventing a fall. To be fair to physics, she was.

We had intentionally structured the deal to trigger a standard review hold on large withdrawals. If you’ve ever managed panicking money, you know that ninety days is less about paper than human temperature. We didn’t need to trap anyone; we needed to prevent self-harm. It also had the delightful side effect of taking Frank’s favorite tool—anger-as-bludgeon—out of his hand for a quarter.

Within twenty-four hours, the Seattle Business Journal had put my face next to the words surprise takeover and turnaround play. By week’s end, the state financial regulator announced a review of Sterling’s previous management practices in the capable monotone of people who use words like findings and consent order for a living. We offered our full cooperation, not because we were saints, but because we were grown-ups.

Sterling’s clients began sending emails that read like exhalations. “Finally,” one wrote, “someone who answers a message with something other than a brochure.” A widow called to tell me she’d cried when she saw her new statement organized in a way that made sense to people who hadn’t made finance their personality. She had never had a woman explain dollar-cost averaging to her without making her feel nine years old.

And Linda? She called my assistant at 7:03 a.m. like she was ordering a latte at a drive-thru. “Put my son-in-law on,” she said. My assistant, a queer twenty-something who has dealt with worse at his first job moving appliances, put her on hold and slid me a post-it that said, Emergency Enraged White Lady with a doodle of a dragon.

I took the call. “All client communications will go through the portal,” I said, the kind of sentence that infuriates people who think the rules are for other people. “Any request for distribution above normal monthly income during the ninety-day review must be documented with use case and signed by both account holders.”

“We’ll take our money elsewhere,” Frank said in the background.

“You are of course free to transfer accounts at the conclusion of the review,” I said. “Our team can help you do that efficiently if you choose. Meanwhile, our fiduciary duty—”

“You’re not our daughter anymore,” Linda said, low, like the monster in a fairy tale telling the hero it knows her name.

“I was never your piggy bank,” I said, and hung up.

Part Two

Buying Sterling didn’t make the market kinder or the world less petty. It made me visible in rooms where men like Frank have not historically enjoyed seeing women like me appear on the shareholder register. It also meant I had to do the work. I have never been afraid of work.

We triaged the client book like a field hospital. Retirees sitting on aggressive growth funds inappropriate for their age and income needs were shifted into laddered bonds and well-diversified low-fee funds. Small business owners in “exclusive” alternative products that were exclusive of good sense were unwound with grace (and where applicable, a letter to the regulator). We cut fees where we could, explained fees where we couldn’t, and put our financial analyst who can make tax loss harvesting sound like a bedtime story on every call with clients who cried when they discovered they were allowed to understand their own money.

For my in-laws, it was arithmetic and then habit. Their monthly income dropped because the math finally got honest. The leased car went back to the dealership with the awkwardness of a promposal declined. The country club, whose salad bar had given Frank a sense of citizenry he mistook for citizenship, sent a letter that read like a breakup penned by someone who spells discretion with a flourish. The house went on the market. Linda cried on the front steps when someone called her property “cozy” in the listing and I did not comfort her because sometimes the kindness is letting people sit alone with the consequences of their choices.

Jason chose a lane after a period of wobbling that required more grace than I had to give and that he tried to borrow from me in late-night apologies that smelled like regret and bourbon. “You laughed,” I said finally, not as an accusation but as a fact. “You watched them take my dignity and you found it funny enough to breathe air into it.” He wept. He said he had been afraid. He said he had been raised in a house where going along was how you received love. That is not an excuse; it is an etiology. We went to counseling; he learned how to say to his parents, “No, that’s disrespectful,” without adding, “But she also—” We learned how to be a unit instead of a duet where one person plays the melody and the other person mimes.

The press did what press does: built a narrative arc with a villain (old bad finance), a protagonist (young scrappy tech), and a moral (diversify your leadership, for God’s sake). They used my face and Elena’s chin tilt to sell magazines for one news cycle. A month later, a bigger scandal elsewhere knocked us off the carousel. That was fine by me. I prefer being underestimated until there’s nothing left you can do about it.

In the third month of the review, the regulator mailed us a letter with findings in it. It was exactly what you would expect: stern, precise, with numbers that say someone had a yacht payment due without saying it. It required Sterling (now us) to make certain clients whole for fees charged on assets that should have been excluded, to update our disclosures, and to submit to an independent oversight audit for a period that would give Frank an ulcer if he even knew what oversight means in this context. We cut the checks without appealing; we corrected the errors like adults. The regulator expressed mild surprise and an unwilling smile when Elena sent a note thanking them for “helping us clean our own kitchen.”

There was a moment, in month four, when Linda tried to stage a comeback as an aggrieved philanthropist. She started an Instagram account for the charity auxiliary she had once attended as a means of networking and posted a photo of herself holding a folded flag in front of a nonprofit’s new office we had funded as part of Sterling’s required community reinvestment. The caption read, “Giving back even when some people take.” The comments were unkind. She deleted the post and took down the account. Somewhere in that humiliating feedback loop, a woman who had never needed quiet learned to occupy it.

And then the annual Sterling client event turned up on the calendar again like a test you’re old enough now not to study for because you’ve learned the subject. We didn’t call it a gala this time; we called it an annual report to the people whose money made our lights turn on. We served decent food and asked our analysts to present three case studies where honesty had cost clients fees and saved their retirements. We put the compliance head on stage and let him describe—in human terms—what a fiduciary duty means beyond a framed certificate in a hallway. We built a Q&A into the agenda before dessert and found that when you treat people like grown-ups, they ask better questions than any vice president ever has in a boardroom.

Linda and Frank arrived early, as if to change the seating chart. They stood near the coffee station and looked like a couple in a play where the set has been removed mid-scene. Frank spotted me and started to come over; Linda reached for his arm in reflex, then let it drop. He put his hands in his pockets like a boy.

“Megan,” he said, embarrassment and pride making a commodity of my name. “We need to talk about the distribution schedule.”

“We will,” I said, the way one says we’ll schedule dental cleanings and appendix removals—necessary, not urgent, the kind of thing a citizen does.

“I didn’t know,” he added, eyes on the buffet because he could not bear to put them on my face. “At the wedding, I didn’t—” He cleared his throat, a sound like sheets tearing. “We were wrong.”

The apology was a folded thing. He didn’t know how to festoon it. He didn’t need to. Some doors you open into a room where the furniture is already arranged. “Thank you,” I said, because grace was cheaper than rage right then, and I am competent in both currencies. “Let’s make sure your money lasts as long as you do.”

He nodded and retreated, his relief so palpable I almost wished him a slice of the decent cake.

As the months turned and the world remained indifferent to my private war, Sterling under new management did what we had promised: grew, steadied, sorted. Our assets climbed to seventy-five, then eighty, then ninety million, not because we chased, but because we explained. Old men in beige shoes sat in our conference rooms and signed papers that made their granddaughters’ college dreams less brittle. Women who had been told for thirty years they weren’t “the money person” emailed us with questions and, over time, stopped prefacing them with apologies. A teacher sent a note with a photograph attached of their kitchen table and their retirement binder and wrote, “For the first time, I can see my life in numbers. Thank you.”

Jason and I moved into a smaller house than Linda would have approved of: two bedrooms, good bones, backyard with a fig tree that does not care about your net worth. We had dinner with Elena every Wednesday and instituted a family rule: nobody apologizes for work during soup. On Sundays we drove to the lake and watched families who know nothing of fiduciary duty throw bread to ducks that do not invest.

One Tuesday afternoon, Linda showed up at Sterling’s lobby with a pie. It was the kind of pie someone brings when they’re making an effort but the crust is made from magazine recipes and prayer. “For your staff,” she said to the receptionist, not loudly enough to be noticed by anyone who would think it performative. She looked smaller. She was not wearing jewelry, and the bag on her arm was a sensible canvas tote meant for groceries, not war. “I… we… the condo has a community room,” she said to me when I came out to shake her hand like she was a client. “They asked me to host a financial literacy group. I told them I knew a place that could help.” She handed me a list of names in careful script.

We built a Tuesday series, starting with “What Is in an Account Statement?” and ending with “How to Tell Your Adult Children ‘No’ without Saying ‘We’ll See’.” Linda sat in the back the first three sessions and then at week four asked a question about required minimum distributions that made our junior advisor grin because she’d just made that slide better. Frank came to one class and tried to argue with a chart; he lost gracefully and brought donuts the next week.

It took a year for me to believe the new shape might hold. It took two for the rumor mill to stop using our names as seasoning, the way people do when their dinners are bland. It took three for my father-in-law to use the phrase my daughter-in-law’s firm without choking on it. It took four for me to stop flinching every time someone toasted. On our fifth anniversary, Elena raised her glass in my kitchen—low light, no chandeliers, a chandelier would have looked ridiculous in that room—and said, “To the day an insult turned into an acquisition.”

Jason looked at me over his mug and tilted it in a way that felt like a vow. I thought of Linda’s first toast and of my measured walk to the podium and of the moment a widow cried over a statement she could finally read. I thought of how many people think a door is a destination. Sometimes it is just the frame you install around yourself and then step through because you built the room on the other side.

After dessert, I checked the client portal the way other people check their kids sleeping. A new message glowed: Just wanted to say thank you. I never thought I would enjoy reading an account statement. It makes me feel like a person, not a mark. I typed back, That’s the goal. Welcome to the adults’ table.

On quiet mornings, I still run the route that skirts the lake. Sometimes I see Linda on a park bench with a notebook, writing things she needs to remember before they leave her. She always waves. Sometimes we sit for a minute and talk about pies and about how much less expensive it is to be decent than people think. Sometimes she says nothing at all, and we look at the water as if it remembers what it is to be left in the rain.

The thing about being called a gold-digger is that you learn to hear the untuned notes in other people’s songs. The day you stop dancing to it is the day they realize they don’t know your steps. I did not buy Sterling to control my in-laws. I bought it because I could make it better. I made it better because people deserved it. The fact that in being better it also contained my revenge is the kind of poetry even Frank, eventually, learned to applaud.

When people ask me for advice in rooms with bad lighting and good coffee, I tell them this: strategy is just patience wearing steel-toed shoes. Let them call you names while you finish your homework. Let them joke while you witness. Let them toast while you sign. And when the microphone comes to you, use all your teeth when you smile and speak in declarative sentences. Then go to work. The work will be the explanation and the ending and the epilogue you get to write.

And if, someday, someone raises a glass to call you lucky, raise yours back, higher, and say, “To all the luck I made.”

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

I Paid $8,600 To Help My SISTER Move Abroad. Then MOM Texted “You Don’t Count As Family”. CH2

My Parents Said: “I Paid $8,600 To Help My SISTER Move Abroad. Then MOM Texted ‘You Don’t Count As Family’”…

End of content

No more pages to load