My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately

Part One

My name is Ellie Lewis. I’m twenty-seven, a stay-at-home wife in my third year of marriage to the boy I once doodled in the margins of my geometry notebook—Easton (“East” to everyone who’s known him since freshman year). If you’d asked me a month ago to summarize us, I would’ve used easy words: steady, affectionate, ordinary in the good way. We never had drama. We never had to survive anything that required capital letters. We married our high-school friendship and wore it like a favorite hoodie.

“Take care. See you later,” he called that morning, the way he always did—keys in one hand, thermos in the other, tie askew because he prefers almost put together to fussy.

“Will you be working late today, too?” I asked, wiping a ring of water from the counter with the heel of my hand.

“Yeah,” he said, without the guilt he used to add to the admission. “My boss invited me out for drinks, so I’ll be late. Don’t wait up—go ahead and sleep.”

We have a system. He works; I run the house as if the house were my full-time job. It isn’t a philosophy so much as the story we fell into: I like laundry done right; he likes to be able to say “my wife makes the best soup on earth” without adding that he chops the onions. I vacuumed. I cleaned the bathrooms. I changed the sheets. I hummed along to the playlist I built in college and tried not to think about how, for the third week in a row, “drinks with the boss” fell on the last Thursday of the month, the same day East had ceremonially moved money around on his banking app while I was stirring pasta.

When I got to his study, the door was ajar. It is never ajar. “You don’t need to clean my study,” he’s said since the first week we moved in. “Work stuff. I can’t find anything if it gets moved.” It has always been his room, in the way couples sometimes draw circles around one part of the map and write mine on it in invisible ink.

I hadn’t been in there in months. The room smelled like stale coffee and whatever cologne he bought after his promotion last fall. Papers draped the desk like fabric. A file drawer refused to close because someone had introduced too many folders to it with a kind of blind optimism. A sweater he wore when he stayed up late hung over the back of his chair like it had tried to leave and given up.

He told me he “tidied” every Sunday. He did not.

How does he find anything? I thought, not resentfully—protectively. Systems are how busy people show love to their future selves. I made a deal with myself to only reset things that would not risk rearranging his brain. Coffee mugs to sink. Pens corralled. Receipts stacked. I worked across the desk like a tide, and that’s how I found it—a red planner I had never seen before, the kind with a stitched spine and thick pages that make your pen behave.

I don’t go through his things.

That’s the part I told myself while my hand flipped it open.

A photograph slid out and landed face down by my forearm. My fingertips were a heartbeat ahead of my thoughts and turned it over.

Easton, in a shirt I had never seen, the sleeves rolled the way he used to roll them to flirt with me, holding a baby with that instinctive caution men of any age use with new life. And against his shoulder, the face of a woman I recognized because recognition, when it hurts, is a full-body experience: Claire. High-school Claire. My three-years-in-the-same-class literally-never-his-type Claire. The girl who signed my yearbook We’ll laugh about this in ten and then never called.

The photo was lit soft the way churches light everything. The woman wore white. The baby wore white. East wore the look of a man who has just been handed the shape of his future.

Christening, I thought, tasting the word and hating the taste. My chest tightened so fast it felt like a joke.

Whose child? Why is he holding him like that? Why is she—why is she there? Why didn’t I know?

The planner was a map once you recognized the country: dates scrawled with outings and firsts. Scattered among “team dinner” and “site visit,” lunches on Fridays that weren’t Fridays until I looked at the way the ink bled and realized someone had written on Saturday to look like Thursday. Claire + E — park, C+E — OB appt, [child’s name] 6 mo shot. Pages tipped forward like dominoes, knocking denial into the past.

At the very back, tucked into a brown envelope that tasted like metal when I licked it open, a Second Act: a divorce petition, filled in everywhere but the part where the pen commits to the lie.

I stared at it until the language on the page stopped being letters and started being hiss. He had filled out the form. He had signed his name the way he signs for packages when the delivery guy asks if anyone is home. He had not told me because telling me would have made it real. He had a planner for a life, and I was not in it.

My hands shook the way hands shake when your body remembers it was built to run from tigers.

If you had asked me a day before what I would do if I found a photo like that, I would’ve given you an answer that smelled like patience. “Talk,” I would’ve said. “There’s always a story with people. There must be something, some explanation, some…” The part of me that learned cheer at eight years old still loves a pep talk.

The part that opened the planner was done rooting for the wrong team.

He came home later, exuberant with the boyish energy that only breaks the surface when men think they have outsmarted the inevitable. “I’m home! God, I’m beat,” he announced to the house, which did not applaud.

“Welcome back,” I said, and I hate that my voice still carried the percentage of love I had spent three years pouring onto his dinner plate.

“You’re awake?” He sounded delighted in a way that made me remember I used to love being the reason he did. “The boss got blitzed. Wouldn’t stop making me stay. Kept insisting I drink with him.” He laughed like he wanted me to laugh too.

“Did you really go out with your boss?” I asked. I kept my tone flat because people hear exaggerated worry and rise to the bait.

“Yeah—why?” He tried to look wounded. “You don’t trust me?” He said it the way men rely on questions to make you defend yourself and forget to look behind them.

“It just seems hard on you is all,” I said lightly. “Always working late.”

“Well, as long as you understand,” he said, rewinding himself to his favorite script. “Oh—this month. I’ve been invited on an overnight golf trip on the 23rd and 24th. Boss thing. Career thing. Take care of the house.”

“Overnight with your boss,” I repeated. The numbers unveiled themselves like a magic trick I knew the secret to. His planner had a heart around 23 & 24 — first amusement park trip.

He smiled the smile of a man who has convinced himself he is not lying because he has done it in stages. “You’ve met him—Campbell. The guy I was drinking with today. Nothing like what you’re thinking.”

“Okay,” I said, because okay is sometimes a scalpel.

“Why are you weird?” he asked. “You’re usually all ‘have fun’ and ‘get that promotion.’ It’s important for my career. It makes it easier for us, you know?” He touched my hair. “You’ll forgive me, right?”

“There’s nothing to forgive,” I said. “Don’t worry about me. Go and enjoy yourself.”

He beamed, patted my head—my head—like I was a dog he’d taught a new trick. “I’ll bring you back a souvenir. You’ll like it.”

“I’ll prepare a surprise,” I said.

“I can’t wait,” he said. And for once, he told the truth.

For a month I performed the part of the wife I had been, then I learned the lines for the woman I was going to be. I cleaned his coffee rings. I cooked dinners I plated beautifully enough to photograph. I kissed him when he left in the morning. I asked about his day at night. I told myself to memorize the curve of every ordinary moment because I was about to end them without letting bitterness make them ugly.

On the morning he left, he slung a golf bag over his shoulder with all the theater of an amateur actor in a community play. I kissed the air two inches from his cheek and waited until I heard the elevator reach the lobby before I let myself laugh out loud. Then I did what I had been choreographing: packed the suitcase he never looked inside, slipped my passport into the pocket of the tote where I keep receipts, loaded the trunk, and locked the door as if I were going to the grocery store. I drove to the courthouse on Maple, where the clerks pretend your life is not ending by chatting about shoe sales. I submitted the divorce form, adding the date next to a signature that did not belong to me.

I left a note on the dining table that said Surprise because I am, even when betrayed, someone who enjoys a narrative arc.

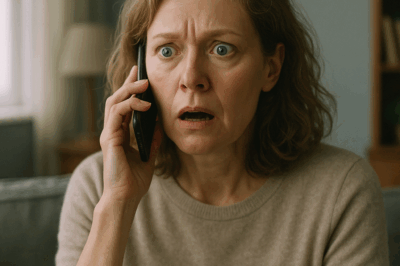

He called two days later, voice pitched high with a panic that sounded almost like grief. “Ellie? Where are you? What happened to the house? What the—” He made a sound like he had stepped into a room where the furniture was not where he remembered it.

“Didn’t I tell you?” I said. “I prepared a surprise.”

“What are you talking about? Your clothes are gone. Your books. Your… everything. It looks like—like I live here alone.”

“That’s right,” I said. “You will.”

“What?”

“You wanted to live alone,” I said. “With Claire. With the baby.”

Silence is an art form. He had not learned it.

“You… didn’t go golfing with your boss, did you?” I asked, kindly, because kindness can be shaped to fit. “How was the amusement park? Did you watch the parade? Did you buy a balloon?”

“You—You looked in my study,” he stammered, like the end of his sentence had run off without him.

“It was a mess,” I said. “I thought I was helping.”

“You had no right.”

“You had a baby with my classmate,” I said. “We can have a PhD panel about rights, if you like. Or we can admit that we are out of the part of the story where that matters.”

He tried indignation. “You promised not to clean my study.”

“You promised fidelity,” I said.

He made a strangled sound. “We—We can talk about this.”

“There’s nothing to talk about,” I said, amazed at how true the words felt inside my mouth. “I filed. We’re no longer married. I let your parents know. They’ll call you.”

“My parents?” His voice cracked like a teenager’s. “You told my mom and dad?”

“Of course. We were spouses. Now we aren’t. People who will ask me questions I don’t want to answer anymore deserve answers they can get from someone else.” I paused. “Also, I assumed they’d like to know they’re grandparents.”

He made a noise like he had been hit with a pillow and the shame was worse than the pain.

“Good luck,” I said, and hung up, because mercy and boundaries share a border.

His parents have always been stricter than the weather. His father believes in duty the way religious men believe in ritual. “Do not burden others,” he would say, when East was late to something. “Consider people’s feelings.” I used to love him for it. I used to think I would be the one to make sure East remembered it when he forgot.

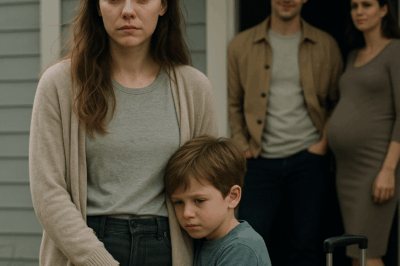

We met at their house the next day not because I wanted to, but because they asked me to, and my own parents raised me to be a person who does not dodge obligation when it belongs to her. The room smelled like furniture polish and lemon. East sat in a chair like a man who had been told to sit in this chair and not that one. His mother had ironed his shirt, a thing she does when she feels useless.

“Explain,” his father said, the way men with authority pronounce verbs.

East cleared his throat. “Two years ago, at our high-school reunion…” He glanced at me, as if asking me to rescue him. I stared at the print of a sailboat above the mantle because I did not trust my face not to tell the story for me. “Claire came up to me. I didn’t talk to her in high school—she was Ellie’s friend. She said she’d always admired me.” He looked embarrassed saying it out loud. “She asked for my number. I said no, at first. We started seeing each other sometimes. I thought it was… it was nothing.”

He lifted his eyes. “She called me one day and said she was pregnant. Five weeks. Said she and her husband hadn’t been… intimate. Said the baby was mine.”

“And then?” his father asked, bored of the parts where intentions buy you nothing.

“She said she was divorcing him. She wanted me to divorce Ellie. She said if I didn’t ‘take responsibility’ she’d tell everyone.” He swallowed. “I panicked. I told her I’d figure it out. I started the paperwork. I didn’t know how to… how to say it to Ellie.”

“You were going to show me a fake dossier of my own cheating,” I said. I pulled an envelope from my bag the way magicians pull rabbits: not surprised because I had always intended to do it. “Receipts. Business cards. Photos of me having lunch with my coworker three times in the same month. Did you think you invented framing?”

He stared at the envelope as if it were a mousetrap. “I… I thought… if you thought you had ruined the marriage, you wouldn’t want anything.”

“You didn’t want to pay alimony,” I said.

He flinched. His mother made a small noise like a teapot catching fire.

“I never wanted to leave you,” East blurted. “Not really. I—Seeing the baby—I thought maybe… but then I thought of you and—” He looked at me the way he used to look at the math test he hadn’t studied for: desperately, as if wanting the answer were the same thing as having it.

“If you had loved me,” I said, because soft truth is the kind of weapon that doesn’t explode but renders a person unable to hold anything, “you would have told me. You would not have made a folder called proof and filled it with a story where I am the villain and you are the hero.”

He opened his mouth and closed it. Color did weird things on his face.

I turned to his father because the man in the chair across from me had once told me I was the kind of woman he had hoped his son would deserve. “Child support,” I said, “is a separate line item from alimony. He will pay both.”

His father nodded as if a ledger were involved—which, in a way, it was. “You will make this right,” he told his son. “Some of our names mean something. Remember that yours was given to you by people who expected you to honor it.”

East sagged. “What do you want?” he asked me, as if I might say something like forgive me.

“An apology,” I said. He blinked. “And forty thousand dollars.”

He did the math in the air, then lost hold of the numbers. “Forty—? There’s no way—”

“Two years,” I said. “A child with another woman. A planned betrayal. False evidence. Forty is the beginning of the conversation. It could easily have been more.”

“I have a baby,” he said weakly. “How am I supposed to—”

“Help him,” his mother hissed at me, the way she hisses at recipes that do not come together the way the photo promised. “You never had children. You don’t understand.”

“I understand that you do not get to use baby as an eraser,” I said. “I understand that a man who lies to his wife and then tries to make her pay for his lie is not a man who should be trusted with a calculator. I understand that if the math is hard, he can figure it out with the woman he chose, not the one he betrayed.”

His father’s mouth flattened. “Pay it,” he said. “Or consider yourself no longer connected to this family in ways that matter.”

It is amazing how quickly a person can decide to be an adult when his childhood is at stake. East nodded. He signed the letter my lawyer had typed. He avoided my eyes. He didn’t pick up the envelope with his name on it. I took a breath I had been holding for a month.

There was one more thing I had to do that day, not because it was legally necessary but because some stories deserve footnotes that teach them how not to repeat. I called Claire on the walk home, the way you call a number you should delete before you memorize it by accident.

“You ruined everything,” she said, in lieu of hello. “He told me you know. He told me you’re demanding money.”

“You ruined your own marriage when you made choices with a person who had already made vows,” I said, in the calm tone I learned in an office where deadlines conspire with egos. “I am asking you to pay the share of the damage you caused. Alimony is not a tip. It’s not optional. You knew he was married, and then you threatened him with a baby. If you wanted a family, you could have built one without stealing from mine.”

“I have a child,” she said, on the word as if it were a magic spell.

“That child needs diapers and pediatricians and school,” I said. “Those are separate line items from the consequences of your behavior. You wanted him. You used a baby to pressure him. Now use your ingenuity to figure out how to live with what you did.”

“You don’t even know what it’s like to be a mother,” she snapped.

“I know what it’s like to see my future stolen,” I said. “I know what it’s like to not sleep because the person next to you is lying. I know what it’s like to be told to pick up the pieces of someone else’s mess and be grateful for the exercise. Pay the alimony or I’ll see you in court and ask for more. Your choice.”

She hung up. My lawyer called three days later to say a small first payment had landed. I put the money into an account labeled For the version of me who makes good choices because humor outruns bitterness if you let it wear better shoes.

Months went by. I moved into a sun-struck apartment on the other side of the park, one without a study and without doors that close on secrets. I started sleeping with both pillows, because I no longer had to pretend I liked the flat one. I went to the grocery store and bought olives without worrying he would think they were a waste. I found work at a design firm so fast I wondered if I’m fine is sometimes the tonic we need to remember we built ourselves.

One Saturday, carrying oranges and a bunch of tulips because I’m a woman who writes her own symbols, I saw June—East’s mother—by the tomatoes. She saw me and hesitated, the way you hesitate when you want to say something kind but have spent a decade practicing criticism.

“I heard,” she said finally, tipping her head to the side in a gesture that made her look more like East than I was prepared for. “About… what happened afterward.”

“I prefer the future tense,” I said, because I am sometimes smug when I have survived something.

“They were going to marry,” she said, in the tone of someone reporting the weather out of habit. “But it turns out that baby…” She took a breath that said she had had to practice the sentence. “Isn’t his. She had a test. He had a test. He confronted her. She confessed. The child looks like her ex-husband. He was fooled. He says he was fooled. It doesn’t matter. He cheated. He lies. He is learning. The courts will… decide what they decide.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, and was not lying. “He’ll survive this and become something I won’t know.”

She nodded, as if I had given her permission to be a mother who does not take pain personally. “Be happy,” she said shortly. “Since he made you unhappy. Do it so thoroughly he can feel it if we mention your name.”

“I intend to,” I said, and she smiled the kind of smile a woman gives another woman in the produce aisle when both of them know that pain and joy have the same destination if you walk long enough toward the light.

The tulips were more red than the photo in the catalogue had suggested. I took them home and cut the stems at an angle and put them on the table next to the letter from my lawyer that said Paid in a line item beside a man’s name I no longer said out loud. I made myself a sandwich with olives in it and laughed because I could.

The study door in my old apartment probably stays closed now. I don’t know. I don’t care. I walk past the block where we used to live sometimes on my way to the bus because I am a person who refuses to let a street become a ghost. I don’t hurry. I don’t slow down. I am not grateful, and I am not angry. I’m simply not there anymore.

Part Two

You can measure the end of a marriage in things as small as teaspoons and as large as court transcripts. The emotions that arrive afterward are not orderly. Some days, relief is the first thing you feel when you open your eyes; other days, the idea that you lived with a man who thought evidence was a gift makes you so tired you eat cereal for dinner and call it a victory.

I built a life that did not require me to forgive him to keep moving.

Mornings were the easiest: coffee on the balcony; a neighbor’s dog who decided I belonged to him and brought me a slobbered-on tennis ball; emails with words like deliverables and scope; a walk to the florist because I am trying to be a woman who buys herself flowers without a reason. Afternoons had a rhythm—work, laundry, water the plant whose leaf names I learned like poetry. Evenings became mine again. The TV asked me nothing; the book on my nightstand asked me to remember that language can rebuild things you thought were rubble.

I am not noble enough to say I never think about East. I hope I am honest enough to say that when I do, it is a thought like a bird that notices a window and veers away.

Twice a month, my lawyer texted me confirmation of a deposit. It felt like a metronome for a song I didn’t write but was still forced to dance to. I moved the money without looking at the numbers. I indexed my future in small acts of autonomy—baking a cake on a Wednesday for no reason; taking a class that taught me how to use a drill so I would stop being afraid of holes in walls; saying no to a brunch because sleep wanted me more than mimosas did.

Claire paid, too, after a long phone call full of excuses that would have made better stand-up if I hadn’t been standing. “We’re paying for a baby,” she said too loudly.

“You’re paying for a decision,” I said quietly. “The baby is not an excuse. It is a person. Teach it how to live with consequences by demonstrating how consequences work.”

She hung up on me. Sometimes justice doesn’t look like a gavel—it looks like a number in a bank account made of Vanessa-in-accounts-payable-at-her-desk sincerity.

Then came the day at the grocery store, the way stories about karmic rebalancing always come on days when you think you are over the genre. June (his mother) told me the child wasn’t his—they believed it, then they tested it. “He’s in hell,” she said, and I almost said aren’t we all, but the produce section is not the place to practice philosophy.

“I hope he gets the help he needs,” I said, and meant it, because I will not spend my life feeding the part of me that survives on other people’s misfortune. He is a man who wanted a story with himself as a hero. He wrote one. He cast a baby in it who wasn’t his. The credits will roll without me.

There is a particular quiet to a house that wasn’t empty before and is now. You can call it loneliness if you like. I call it room.

In that room I made a list of rules for the version of me who appears whenever I forget what I learned:

-

Never mistake a closed door for privacy. You are allowed to knock. You are allowed to ask. You are allowed to insist on being let in.

Do not build a life solely in reaction to other people’s choices. Choose.

If ever the future does not include someone who claimed to love you, believe that this omission is either mercy or a sign.

By spring I had stopped being surprised by the ways I was okay. I stopped giving myself points for not crying. I stopped apologizing for being fine at inconvenient times. I went to a concert alone and cried there because the lights were too beautiful. I learned to roast a chicken in a way that made my apartment smell like competence.

I wrote to my high-school friend, the one who introduced me to East at lunch when we were sixteen and said you both owe me forever the night of our wedding. I told her the whole story because the past deserved a better ending. She wrote back and said Claire always wanted what wasn’t hers. I am sorry you were what she wanted.

Forgiveness is a hobby some people adopt because it makes them feel like saints. I am not a saint. I am a woman who knows resentment is a poor landlord. I have forgiven East enough that if he walks into the café where I sometimes buy a cookie, I do not leave. I have forgiven Claire enough that I hope she becomes a better mother because she learned the hard way that deception is not a foundation.

This is the part where I tell you what happened to everyone because closure is an intoxicant and I refuse to pretend otherwise.

East: Paid the alimony. Paid the lawyer. Paid the child support he thought would buy him absolution until the envelope on a Tuesday morning told him he’d financed a lie. He moved to a rental that smelled like old fried onions and learned that regret looks like a drawer full of unpaid bills. He calls his father more. He says I’m sorry to his mother like it is a language he didn’t know he had to learn. He will be okay if he decides to be.

Claire: Discovered the limits of narrative control when DNA refused to obey plot. She kept the job she was going to quit because money does not arrive on the wings of a man’s intentions. She mothers the baby who did not benefit from her scheme. She pays me every month, and sometimes I imagine that the money vanishes from her account before she can press confirm, like conscience does. I hope she teaches her child not to repeat this, only because the world is hard enough without inherited deceit.

His parents: They send me a card at Christmas that says only Wishing you peace, and sometimes, if the handwriting is messy, thank you. I do not answer because we understand each other in ways that do not require stamps.

Me: I work. I sleep. I love my own company in a way that makes it easier to believe I will eventually love someone else’s again. I am not looking; I am scanning. I do not date men who turn their phones face down on tables. I do not date men whose eyes close when they say the word hard. I do not date men who think secrets are romance.

I file this last part because it matters: another woman might have opened the planner and chosen confrontation before exit. Another woman might have stayed for the apology and left for the relapse. Another woman might have burned the house down. I gathered my things and left a note that said Surprise because I am that kind of woman. My revenge was not an explosion. It was administrative—swift, tidy, and written in legal ink.

When the tulips in my kitchen wilted, I did not mourn them. I learned how to trim the stems and keep the water clean. They lasted longer than I expected. I will buy more next week, regardless of whether anyone else sees them. That is what this is, now: the practice of creating beauty even though no one has promised it to me.

If the past calls, I do not answer. If the future knocks, I do not hide. And if anyone asks me what I did when I found my husband’s other life sitting in the study like a heart I wasn’t allowed to see, I will tell them the truth:

I opened the door. I looked. I believed what I saw. I filed the papers. I made coffee. I went on.

I put a vase of red tulips on my new table. I wrote a new planner that had only one paragraph on every page. It read:

Choose yourself.

END!

News

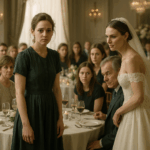

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls ‘Help with the Funeral!’ Me – ‘My MIL died 3 years ago’. CH2

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls “Help with the Funeral!” Me — “My MIL died 3 years ago.” Part…

End of content

No more pages to load