My Husband’s New Wife Came to My Door With a Greedy Smirk. She Said, “We’re Here for Our Rightful Share of Your Father’s Estate. Move Out Immediately.” I Smiled as My Lawyer Walked in Behind Her…

Part One

The knock was the sort of polite, bodyguarded punctuation that precedes bad news. I wasn’t expecting anyone. We had been careful—my father and I had both been careful about most of the things people worry about once they become adult enough to manage property and grief. Still, there are always moments in life when the normal logic of privacy frays and someone else’s brass entitlement pushes inside.

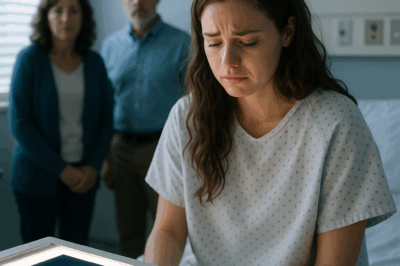

I opened the door and there she was, everything polished to a particular angle of confidence—red lipstick, a haircut that looked professionally perfected yesterday, shoes that clicked in a way that announced money. She had the look of someone who had rehearsed victory in mirrored bathrooms. Beside her, less composed and more pale, stood the man who had once told me I was his sky. With his jaw a little slack and his face the color of someone who’d grown tired of the role they’d chosen, he shuffled his feet as if asking permission to be forgiven and wishing, somehow, to be forgotten.

“We’re here for our rightful share of your father’s estate,” she said. The sentence was iced with sugar. “Move out immediately.” She pronounced the words like a verdict recited in the wrong court, as if the rightness of it could be conjured by saying it loud enough in front of my doorway.

My fingers curled against the doorframe not from fear but from a habit born of long nights where I taught myself restraint. If she had looked closely, she might have seen the quiet in my eyes—an absence of surprise and the small, private arithmetic that had been running in me for months. There had been, after all, a procession of tiny things that had led me to the moment: the perfume in his coat that had not been mine, the business trips that mapped onto moments when his phone went dark, the odd receipts for dinners at restaurants whose lights I knew by heart because he had once taken me there on an anniversary.

There was a time I would have bled quietly for him. Love, in the version I had tasted, asked for foolishly sustained loyalty, for the consumption of the self in the name of a person who promised to hold your center. After my father died and the house—our house—filled with schedules of mourners, gardeners, and lawyers, I had clung to him like a raft. I didn’t know I could drown in the proximity of a man who had one foot already outside our marriage.

I stepped aside. The motion was small and civilized. The woman—now his wife—brushed past the page of wallpaper and the brass bell on my wall and folded into the light of the parlor as though she owned the angle of the window. Her smirk widened when she thought I’d been stunned by the audacity. For a sliver of a second I thought she expected me to crumble in the modest theater of my home.

Then my lawyer emerged from the hallway behind me, tall and deliberately ordinary in a gray suit that somehow made him look both more dangerous and duller-than-danger. His name was Marcus, and I had hired him not out of drama but in the stripped practicality of someone who refused to gamble on the calamities other people could manufacture. He stepped forward with the slow, controlled gait of someone about to read an iron rule aloud.

“Mrs. Pell,” Marcus said, speaking first to her as if she were the defendant in a case she had barely considered, “I believe you are mistaken.” His tone was practiced and slow; the sound of it seemed to rearrange the room. Mrs. Pell blinked. Her husband gave a tight choked laugh that fell like a broken bell.

I have, over the last year, built a list in my head of what makes a person wealthy and what makes a person rich. Wealth is an account with many zeroes. Richness is a lattice of things: reputation, regard, and what people owe you when they call you by your name. That list had been instrumental. When my father—an architect who loved books and the smell of pewter and ink—was seized away by a late diagnosis, he had made his choices with the clarity that illness sometimes forces. He had not trusted that sentiment was a sufficient legal architecture for the people he loved. He had set up a trust. For months before he died, he had asked me to tour the papers, to understand the clauses that were written not to be cruel but to be careful.

He had insisted on an anti-contest clause in the trust: a standard provision in many estates that strips challengers of their inheritance if they contest the will and lose. He’d insisted on a spendthrift clause that would prevent anyone from pledging estate assets for loans, and he’d made me the primary beneficiary with a contingent remainder that favored no spouse but the line of his blood. He’d been meticulous. He had also been, in his later years, more suspicious than he had been in his robust middle age. “Money is an honest mirror,” he told me once, pushing his glasses higher. “Make sure it reflects the right face.”

So when Marcus handed Mrs. Pell a packet of crisp, single-spaced pages and slid them open with the little knife-sharp sound of someone who had been preparing an argument for a long time, the woman’s smile began to fissure. “This estate is legally protected,” Marcus said. “It is bound to my client exclusively. Neither you nor your husband holds any legal right to it. In fact, we have already received sworn affidavits exposing several fraudulent statements your former husband made during the divorce proceedings.”

I realized she had thought herself an entitlement in a world that confuses audacity with ownership. She had expected argument and bargaining where there was none to be had. Instead she got legal language that functioned like a forcefield.

The rest was like watching a paper house meet rain. Mrs. Pell forced her jaw into another rehearsed expression. Her new husband, the man whose hands I knew and whose fingerprints used to be the only ones I trusted on my shoulder, said something about fairness, about shared life, about how we had once been a family even if we were not now. Marcus listened, his face slow to betray feeling. He asked for one clarification and then said, flatly, “The anti-contest clause applies, and your husband, by attempting to assert access to assets through misrepresentation, stands to forfeit any gain. We are prepared to pursue damages for the fraudulent statements in the divorce. You would be advised to leave.”

Their smirks died. But the woman tried to find a new weapon—pity or moral accusation. “You—you’re kicking us out? He needs a place,” she snapped. “This house has parts that are shared. You can’t just keep everything because you feel slighted.” She used the accusatory “you” as if ownership could be declared by noise.

“What you lack is standing,” Marcus said. “What you propose is a contrivance. Leave. Or we file today.” He folded his papers, neat as if folding a map back to the place where the trail ends. The pallor in her face was a small gift to my quiet pride. She turned, one shoe catching at the threshold, and left with her husband trailing, their departure soundlessly urgent—an exit stage-left designed by shame. I closed the door gently after them.

Silence settled over the house like a clean blanket. It felt, absurdly, like a triumph—one I had not permitted myself to seek. For years I had loved a man who had kept his pleasure in a narrow hand. We had ordinary fights; we had ordinary reconciliations. The thing I had misread: he was not a man who kept a map of commitment. He was a man who collected comforts and traded them when something shinier promised less resistance. When he had moved out—quieter than the divorce papers—he had thought that my grief would be a soft economy to exploit.

I walked through my father’s study, the room that had defined him: the settled leather chair under the south window, the map pins in a frame of places he had fielded his hands over, the little plaster models of bridges he had once said were the honest architecture of a life. He had taught me patience—in the way a person teaches by example rather than sermon; his own version of fortitude had been to finish a difficult drawing, not to tell people about how bracing he could be when the weather turned.

My patience had become a plan. I had not snapped in anger at the first sight of the perfume on his coat, but I had done the far more boring and far more effective thing: I had called a lawyer. I had read. I had lined facts and receipts and small betrayals into a file. There is a particular kind of revenge that feels like a polite ledger—paper, ink, procedure—rather than a scene. That night, I stood in my father’s study and listened to the house breathing, and it felt, for once, like my house rather than a memory.

What Mrs. Pell did not know—and perhaps what none of them had calculated—was that my father’s estate was never an appetizing pie to be carved by the loudest claimant. He had been deliberate. He had been a man who counted what he loved and then arranged legal structures to preserve those things. When you are the named beneficiary and you have an attorney who knows the law’s muscle, the sudden arrival of someone who thinks entitlement is a currency becomes an interesting display rather than a threat.

After that day there was, predictably, the paperwork that followed confrontation. Her smirk had been replaced by the kind of desperation that looks almost childlike when it’s not dressed up in false confidence. Lawyers wrote letters. They asked for beastly things. “We demand mediation,” one of their lawyers wrote. “We insist upon equitable distribution,” another insisted. Marcus replied in the same steady cadence that had unseated her at my door. He filed motions to dismiss their claims and gave notice of the pending suit for fraudulent misrepresentation.

In the quiet that followed, I walked the house like someone relearning a map. I found things my father had left in drawers: an old letter with ink so pale it looked like memory, a pair of pressed stems from a bouquet he had once given my mother. Grief and relief are not opposites; they are handholds on the same cliff. I allowed myself a small pleasure: a cup of tea brewed not in the haste of coping but with the patience of someone who knows how to wait.

That night, alone in my father’s study, I thought about all the little calculations that people skip when they think of love as that hot, immediate thing. They often forget that love, to survive, needs something dull and bureaucratic: trust agreements, joint accounts, prenuptial clarity. Those things are not romantic. They are necessary. They are the scaffolding behind an outwardly tender human thing. My father’s documents had been that scaffolding. My lawyer had been the hands who knew how to hold onto it.

A week later, when the first motion was filed, I sat in Marcus’s office and watched the document as if it were a photograph of some violent moment. He walked me through the motions: the alleged fraudulent statements in the husband’s divorce filing; the timeline of misrepresentations about property ownership; the request for punitive damages under the statute that penalizes litigation that misleads the court. It was all very legalese and precise. It felt powerful, like the careful throw of a net around the thing that had tried to slip away.

“People confuse not caring with not knowing,” Marcus said. “He thought you wouldn’t fight. He thought you’d be humiliated into silence. What he didn’t account for is that you are good with lists—and, it seems, you’re good with endurance.”

I smiled because it was true. I had been good at lists long before my father taught me how to lay bricks. Lists turned into plans, and plans turned into things I could use.

But a legal victory is not the same as closure, and I knew that the weekend at my father’s house would be filled with calls and whispers. People are curious animals. They like to place themselves at the center of other people’s stories. Gossip arrived in polite packets—neighbors asking how I was, cousins pressing their grief into the shape of concern for propriety. I answered the calls in small measures and then, with the ungraceful dignity of a woman who was feeling something like a new horizon, I set to work on doing the practical tasks that grief leaves in its wake: sorting papers, calling accountants, planning for the charity fund my father had wanted to start in his village.

That week, I met my old husband only once more, in a setting that was mercifully public: the parlor for a scheduled exchange of documents. He arrived with his new wife, who now looked drawn at the edges as though all the smile practice in front of mirrors had drained her expression. They had hired a lawyer in the hopes that noise could fashion something that looked like entitlement. Marcus had prepared a concise, cold file. The exchange went exactly as one would imagine: the short, brittle pleasantries that people use when they have nothing to say and want the sound of being polite to get them out of the room quickly.

He tried one small tactic. In front of my file cabinet—an oak treasury of things that belonged to my father—he said, low and unnecessarily intimate, “You always did like to keep things. Don’t you think some things are better shared?” I looked up and the sentence felt like the scraping of a fork on a plate. “Some things,” I said, “are not objects. Some things are intentions. My father tried to protect his intentions from people who couldn’t keep them. If you think there is some right you hold, those motions are recorded and available to the court.” He looked down at his feet. The look was not quite shame; it was the look of someone who had traded in the currency of being liked for the immediate pleasures of being desired.

That night, the house felt like a place with a future rather than the wreck of a memory. I made tea again and sat in my father’s chair, and for the first time in months I was not trying to be small. I was making a list.

Part Two

Lawsuits are not cinematic, at least not the way movies make them seem. There are depositions—morning-after conference calls, stacks of exhibits and email chains that reveal the quiet erosion of a marriage. There are motions to compel discovery and affidavits and spreadsheets showing where money goes. My father, who had been an architect, had always loved line items. He thought the world should be as orderly as a drawing. After he passed, I found myself writing legal responses with a kind of pleasure that belonged to someone who likes to make things precise.

The husband, in his filings, had claimed that parts of the estate should be equitably distributed because of the “long partnership” they had shared. The new wife, in emails that read like morning affirmations set to work, demanded an accounting and an immediate move-out notice. It takes only a certain kind of arrogance to confuse friendship and obligation with legal ownership, and arrogance is one of those feelings that makes people believe their own worst myths.

When the trial began, I sat in a wooden chair in a courtroom that smelled faintly of polish and old coffee. The room hummed with procedural quiet. Mrs. Pell sat on the opposing bench with her husband. Their faces were more fragile than I remembered. Lawyers from both sides performed their roles: a complex choreography of objections and exhibits, a battling of testimony that was as much about human motives as about money and property.

The day the judge ruled, I felt the old gravity of our lives sitting on his bench like an old coat. He read the law in a voice that suggested he had been given many sorts of human mess to wrangle. He read the trust. He noted the anti-contest clause that would penalize an unsuccessful claimant by stripping them of any right to the estate. He pointed out that the husband’s divorce filings had included statements inconsistent with the facts he had provided during discovery and that several documents appeared to have been altered or misrepresented.

“Where evidence of material misrepresentation is shown,” the judge said, “the court may impose remedies that include punitive damages when litigation is used as an instrument of fraud.”

It was legal music, not melodramatic, but the effect was the same: an unmasking. He granted summary judgment against the husband on the claim for equitable relief, meaning the attempted claim failed without further trial because there was no legal basis to proceed. He further gave the plaintiff—me—permission to pursue damages for the misrepresentations. The court ordered sanctions. It was not a dramatic fortune, but the moral order it represented was loud.

Mrs. Pell and her husband had to pay for the legal costs they had incurred through their own litigation. The punitive damages, while not designed to lavish me with money, were designed to make the calculus of their action unpleasant enough to deter games of entitlement. In one of those small, sweet legal flourishes Marcus had arranged, the court also granted me a declarative statement of my title, clearing the house of any claim so that their attempt to siege it legally would fail forever.

I remember that afternoon as a narrow, clear thing. The judge’s gavels are not fireworks. They are more like the snap of a seam. But when he concluded, I sat very still and felt the seams settle. The husband left the court like someone who had been partly dismantled. The new wife walked out with a look of clientally-provided dignity—one that seemed to shrink in the presence of finality.

The aftermath was not theatrical. There were, instead, practical consequences. The husband, who had expected the marital dissolution to be an exercise in efficiency, found himself in a strange economic place. Having been the kind of person who enjoyed the indulgences of an easy life paid by a comfort he had not himself always banked, he discovered a sudden shortage of tolerance when the bills came home to him. He had pushed his money around to make room for a new life; the court required him to pay the costs of a suit he had no right to bring.

Mrs. Pell vanished from our neighborhood for a long while. News travels—small town and large alike—and people who had known us both watched and whispered as two people who had assumed entitlement learned the brittle truths about claims that are not founded in law. They seemed to feel shame in the presence of consequence. Shame, in those moments, is a social luxury many people cannot afford for long; it was instructive to watch as it colored them.

But the legal victory was not the closing of the story. True endings are quieter. They arrive like small dawns rather than headlines. I settled into life the way someone learns to read in a new language: awkward at first, then gradually fluent. The house was not a museum dedicated to the past; it became a place that contained memories and also the practical things of living. I set up the charitable fund my father had wanted—he’d spoken about it with the fervor of someone who believed in the gentle economy of help. We started a small fellowship for architecture students from his hometown, the kind of work that made him happy when he was alive. The fund was modest but real. It had my father’s name on it and, for the first time since his funeral, that name felt like a living thing instead of a memory.

Devon—quiet, contrite, often embarrassed by his mother’s soaring aggression—began to visit more regularly. He apologized in ways that were more hands than words. He brought over coffee and stayed to help with broken stoves and with Lily’s science fair. He was not exactly the person I would have chosen for a partner—he was too much like the man who had once been my husband—but he was decent in an unshowy way. We had a strange, slow friendship that felt useful. He needed to learn that people hurt by other people’s mistakes deserve a life that is not defined by the misfortune of others.

What really settled my attention was an unexpected letter from Mrs. Pell. It arrived on a gray morning in an envelope with a shaky script. She wrote, in a tone that attempted both apology and explanation, about grief and the strange hunger it had made inside her. She said she’d gone to therapy. She admitted to being angry in ways she could not control. She asked a simple question: could she come and see Lily once, in a supervised setting? Her letter smelled faintly of personal perfume and fear.

I stared at the letter for a long time. There is a sort of theatrical satisfaction we sometimes imagine in revenge—watching the villain reduced to apology and watching the hero take a higher road. Real life is messier. I had no cinematic desire to see her shamed. I had, at that point, shed any nostalgic love for the man who had left. He was no longer the center of the story and my life had achieved its own axis of being that did not need his light. So I asked Marcus to hold the letter. He kept it in the file and suggested we might respond only if the court allowed supervised contact.

Months later, the court did allow one supervised visit. Jenny—Mrs. Pell—arrived at the community center where we met. She hovered with the kind of caution that looked a lot like fear. She had lost the sharpness of the smirk; what remained was a soft, tentative person. She apologized quietly and then, under supervision and through the filter of a social worker’s neutral voice, she spoke to Lily about memories of Daniel. We watched from a distance while the social worker measured tone and boundaries. There was no reunion, no big moment, and no sweeping closing scene. For Lily, it was a kind of small test: there are people in the world who are complicated, and some of them will be able to be civil in small tastes. She accepted the candy Mrs. Pell brought and then politely refused to go home with her.

Within a year, Jenny faded out of our everyday life. She kept some of the structure of therapy and sometimes wrote vague emails that Marcus forwarded without comment into his file at my request. The law had done its job: it had set a boundary and enforced it, and that allowed us to breath. My father had arranged his estate with the kind of unromantic kindness that saved more than money—it saved the peace to live. For that I will always be grateful.

In the months and years that followed, I discovered how much both sorrow and joy are practical things. They require beds, meals, money, childcare, friends who will come at midnight, and lawyers who know what to look for in ink. I found again the capacity to be light. Lily grew, as children do, into a small person who had taste on how a sandwich should be layered and who liked to argue about the world’s most important things: why ants march in lines, whether dragons preferred caramel or chocolate. She kept our life perishable and bright.

The husband—my former husband—suffered consequences beyond the court. He had made choices that uprooted his life: the marriage that he thought would be an upgrade soured under the weight of instability; the new wife left him when the legal and financial realities caught up. He was no longer the man who had been my safe place; he had become, in many people’s eyes, someone who made selfish choices and then had to live amid them. It was not cruelty; it was consequence.

I did not gloat. Gloating brings its own small bitterness. Instead, I allowed the small pleasures of ordinary days to reassert themselves: the sound of Lily laughing, the smell of toast in the morning, the hum of the radiator in winter. I went back to work part-time at the small gallery that wanted to preserve my father’s legacy in the way that real people tend to do: through a practical, small-handed intervention. We mounted an exhibit once a year in his name for students, and the fellowship grew slowly but honestly. I met people at receptions who loved architecture and who spoke with polite reverence about the small economies of care.

Once, in a moment that surprised me, my former husband called. He had sold his car and was living in a small apartment by the river. He told me in a voice that had been honed by time and trouble that he was sorry. That sound—two syllables of contrition—would once have been a bait. Now it was simply a fact in a conversation. I listened and then explained, without heat, that words were a beginning but not a currency. People are allowed redemption, and sometimes redemption looks like small, repeated acts of repair, not grand declarations.

The finality of the story is not a dramatic tableau. It is rather a string of small endpoints that become the seams of a new life. Jenny did not return to our home as a welcomed visitor. The husband lived with what he had chosen. Lily went to school and learned how to interrupt adults with the fierce joy of a child. Devon and I grew into the steady, practical friends one becomes when life requires the sort of care that is given without strings—he dropped by with casseroles when I was sick; I helped him fix the leaky roof. Marcus, who had once been an instrument of legal action, became a quiet presence at small dinner parties, the sort of person whose company was reliable rather than sensational.

One evening, years after the day the red lipstick smile appeared at my door, I stood in my father’s study and watched Lily practice on a small, imperfect keyboard. She had inherited not his pencil-hand but his love of making things that stood up: little towers of books, models of paper bridges, things that would remain. I thought of the way life had a way of rearranging pain into order and the things that survive the longest are the quietly deliberate actions: signatures on trusts, the making of a charitable fund, the installation of a good lawyer in one’s life. That is not romance. It is survival. It is grace.

I never wished for her small triumphant smirk to be crushed theatrically. I merely wanted justice and the right to sleep in a house that belonged to my father’s intentions and to raise my child without the terror of being unmoored. The law granted me that space. My father, in the small, exacting way that made him the man he was, had planned for it. I honored him by protecting what he had intended: not just money, but the trust of his name and the stability to build something new.

The last scene I will describe is small and precise. It was afternoon light filtering through the study as Lily and I closed the shutters together. She turned and hugged my leg as children do—fast, precise, like a punctuation mark. I looked at her and said, quiet and glad, “We’re home.” She grinned and then returned to building a bridge out of old envelopes. Outside, the street had the ordinary hum of people living, going to the store and returning. Life, which had once been abruptly excavated from under my feet, had been rebuilt with small, unglamorous care.

In the end, the woman who had come to my door with a smirk had left with a lesson: that entitlement unbacked by law is only a bravado, and that the careful architecture of intention—documents, counsel, patience—could render even the boldest greed into nothing more than a brief, unattractive footnote in a life one intended to protect. I smiled then because the world had rearranged itself into something steadier. My lawyer closed his briefcase and said, with a quiet satisfaction that was almost human, “She stayed away.” I poured a cup of tea, and together, on a small, ordinary evening, my daughter and I lived in the house that had been my father’s and now, by design, mine to steward. The door remained closed to those who wanted possession instead of love.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Parents Said My Headaches Were ‘Attention Seeking ‘ The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden. CH2

Parents Said My Headaches Were “Attention Seeking.” The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden PART 1 The migraines started…

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything. CH2

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything Part One The slap arrived with…

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing. CH2

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing Part One Stop. Stop, stop—you’re…

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career. CH2

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career Part One They…

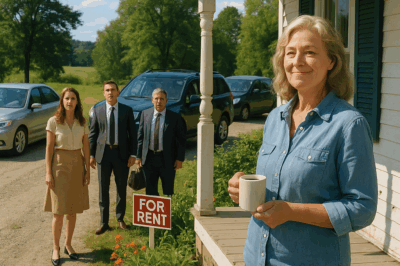

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour… CH2

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour, I’ll be there…

MY BROTHER BROKE MY RIBS. MOM WHISPERED, “STAY QUIET -HE HAS A FUTURE.” BUT MY DOCTOR DIDN’T… CH2

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She…

End of content

No more pages to load