My husband to mistress: “Can’t wait to ditch the child support and run away with you”

Part One

I didn’t hear the clatter of cutlery, the muted jazz drifting from the ceiling speakers, or the waiter who’d been standing at my elbow for a full ten seconds with a bottle of pinot. All I could hear were seven words I’d never unhear:

“Can’t wait to ditch the child support and run away with you.”

At first I assumed the voice belonged to some awful stranger, the kind whose private life spills out too loudly in public. But the deep, confident, practiced murmur belonged to my husband. Grant. And the echoing corridor between the Evergreen Bistro’s restrooms gave me nowhere to hide from it.

“Just a few more months,” he said into his phone. “We’ll be free, baby. Eighteen is a beautiful number.”

He chuckled. My ears rang. My hands went cold and slick at the same time. In the mirror above the hallway credenza, a woman blinked back at me, perfectly made up for what was supposed to be a small family celebration—my son’s eighteenth birthday—her lipstick still neat because the shock hadn’t reached her mouth yet.

I stepped back into the dining room on autopilot, my face already rehearsing a normal I didn’t feel. The Evergreen was all soft wood and softer light; every table held a small glass vase of white ranunculus that tonight reminded me of funerals. Eli sat grinning at our booth, talking a mile a minute about an admissions email and a physics scholarship, his voice bright and wide as June. Grant, for his part, slid into the booth a moment after me, eyes cast down as his thumbs flew across his screen, a secret smile tugging the corner of his mouth like a hooked fish.

To New Beginnings, Eli said when the waiter poured our glasses. “To the best parents a guy could ask for.”

“To New Beginnings,” I echoed. And for the first time in my life, I meant something different than everyone else.

I shifted the square gift box in my handbag—the limited-edition Hublot I’d saved for for months, bought because I still wanted to believe in who Grant had promised to be. A soft, absurd urge rose to hurl it at him. Instead, under the table, I slipped out my phone and typed six words to the only person I trusted to read between the lines:

Urgent. Need discreet meeting. Marcus. Please.

When the check arrived, Grant paid without looking up, slid a wad of bills into the leather folder like he was over-tipping the truth. In the valet line, he kissed Eli’s head and said he’d meet us at home. “Conference call,” he murmured. The phone chirped in his palm like a trained animal.

In the car, I gripped the steering wheel and breathed until the blur at the edges of my vision narrowed back into the rainy Portland night. I’d spent years explaining away absences: late showings, emergency closings, “traffic on 26 is a nightmare.” I had held the long-term as our new normal, told myself that a high-flying real estate career came with late dinners and crumpled pocket squares and a bed that always felt as if someone had just left it. I had raised a son, paid a mortgage, and fixed a blistered roof while holding a marriage together with willpower and calendar alerts.

Apparently, I had been holding a façade.

The following afternoon I sat in Marcus Wright’s office, a room that smelled faintly of leather and competence. He had been a family friend since college—an old debate teammate of Grant’s who’d kept the better parts of himself. His walls displayed framed verdicts and a photograph of his daughters at the Oregon coast, hair alive with wind.

“Tell me everything,” he said gently.

I did. I told him about the birthday dinner, the overheard phone call, the flickers of a thousand small betrayals that now snapped into a discernible constellation. How long had the constellation been there, and I simply refused to draw the lines?

“Lorraine,” he said when I finished, “I can tell you this much already: you are not powerless, and you’re not alone.”

I swallowed hard at the edge in my own voice. “I don’t even know where to start.”

Marcus slid a legal pad across the desk. “First, we gather facts. Quietly. We build a timeline. We find the money. We protect Eli. We don’t tip our hand until you’re ready.”

He asked for bank statements, credit card accounts, titles and deeds, tax returns. I produced a teetering sheaf from my tote bag. I’d always kept our finances tidy—because someone had to—but I had never dug with suspicion. His pen scratched quickly, his questions even and precise.

“When did you last see statements from the brokerage?” he asked.

“Last spring,” I admitted. “Grant said he switched platforms.”

“Of course he did,” Marcus murmured. “We’ll subpoena the rest if we need to.”

“What about Eli?” I asked. “He’s eighteen next week. At what point does the law stop caring if his father does?”

Marcus leaned back, steepling his fingers. “Eighteen changes the child support equation, yes. But it doesn’t erase your rights—spousal support, division of assets, reimbursement for any community funds he’s—how shall we say—reallocated. And it doesn’t erase moral responsibility. As a practical matter, we can secure college expenses in writing. We can also keep custody off the battlefield; he’s essentially grown.”

I exhaled a breath I hadn’t realized I was saving for someone else’s verdict. “I’m not trying to burn it all down,” I said. “I just don’t want him to get to walk away from his mess like it’s a cocktail party he got bored of.”

“Which is precisely why you’re here,” Marcus said. “You came before you confronted him. That’s the difference between catharsis and strategy.”

When I told Eli that evening, the world tilted in his eyes first, then flared. “He said what?” he choked. “Ditch the child support? He said that out loud?”

“Keep your voice down,” I murmured, pressing a mug of chamomile into his hands. “Walls are gossipers.”

“He always told me I was his reason for everything,” Eli said, knuckles white against the ceramic. He rarely cried; stubbornness was our shared language. Tonight, his face worked, and then settled into a new shape of determination. “What do you need me to do?”

“You need to be eighteen and finish physics,” I said. “You need to win that scholarship and go be brilliant far away from this.”

“I can do both,” he insisted. “Dad has a trail. People know things. Assistants. Loan officers. That receptionist who can’t stand him. Let me ask questions.”

I hesitated. The protective part of me wanted to shepherd him into a kind of sunlight beyond all this. But the other part—the one that understood that agency heals—nodded. “No confrontations,” I said. “No drama. You are an honor student, not a private eye. And if anything feels dangerous, you stop, and you tell me.”

“As long as we make him pay,” Eli said through his teeth.

“We make him answer,” I corrected. “Even better.”

The weeks that followed unfolded with the cold clarity of a plan sliding into place. I met with Marcus twice a week. Eli worked his quiet charm on the periphery of Grant’s world—the ash-haired office manager at Silverline Realty who had ordered lunch for Grant and “Clara” for three years (“She always left a note with hearts,” the woman said into her napkin), the bartender at the Riverlight who called Grant “Thursday-night whiskey-and-vows,” the treasurer at Grant’s golf club who’d seen wire transfers to accounts in the Caymans. Eli compiled names; I compiled receipts. Together we built a portrait in paper.

There were hotel folios—same suite number, different cities. There were jewelry charges in a style I’d never wear. There were plane tickets for one attached to texts that implied a second ticket bought in cash. There were gaps where our joint brokerage should have been.

There was also Eli’s graduation cap and gown hanging from the bedroom door, the red tassel punching through my chest every time I walked by. He won the scholarship he had targeted since sophomore year, and the acceptance email made him laugh out loud in the quiet kitchen. The sound shook something loose in me that had been stuck for years.

We decided to do the thing I had never imagined myself capable of: invite Grant over for a birthday dinner he would never forget and finally set the match to his paper life. Marcus insisted on being there. Eli insisted on being there. I insisted on wine.

I cooked what he liked—absurd as that seemed in the moment—lemon rosemary chicken, fingerling potatoes, asparagus with a hint of char. It steadied my hands to do familiar things. I wore a dress that made me stand taller. In the mirror, I practiced looking like someone who couldn’t be unmade by someone else’s shallow plans.

The doorbell rang. My spine went quiet and strong. I opened the door to find Grant on the step, handsome and careless in the way that always looked better from a distance, and beside him a woman with movie-star hair and the skittish eyes of an understudy. Clara. She had the sort of beauty that photographs well in the first week of an affair, and the sort that sours quickly under fluorescent light.

“Lorraine,” Grant said, leaning in to kiss my cheek as if he’d come home from work. “Clara’s been dying to meet Eli.”

“I bet she has,” I said pleasantly. “Come in.”

We sat. We toasted “To New Beginnings,” which now tasted less like irony and more like an invocation. Marcus rose from the living room chair and joined us at the table. Grant’s smile froze.

“What’s he doing here?” he asked.

“Dessert,” I said. “He brought something sweet.”

I set the heavy folder on the table and opened it like a ceremony.

“Let’s begin with your corporate card,” I said, laying out the pages. “I’ve highlighted the hotels. Look how consistent you are with your room preferences. It’s almost sweet.”

Grant went pale under his tan. “This is—Lorraine, I can—”

I put one finger down on the jewelry receipt. “Don’t insult me by pretending I can’t read.”

Clara’s mascara made two gray-black comets toward her jaw. “I didn’t—he said—you told me you were separated—”

“Oh, Clara,” I said softly, too tired to even be unkind. “You believed a man on the phone who sells other people stainless-steel kitchens for a living.”

Grant pressed his palms flat on the table—the pose of a man pretending to be the reasonable party in a doomed negotiation. “Can we do this without an audience?”

“That depends,” Marcus said, his tone pleasant as rain. “Would you like to explain the offshore transfers privately as well? Or the emails you dictated to your assistant back when Clara still signed her name with a heart? How about the line you so enjoyed at the bistro about ‘ditching child support’?”

Grant’s mouth opened and closed once, twice. He looked at Eli, perhaps expecting solidarity from shared DNA. Eli picked up a page and read aloud: “July 12, Riverlight Hotel, Suite 704, two nights. July 28, Riverlight Hotel, Suite 704, two nights. August 11, Riverlight Hotel, Suite 704, two nights. August 25…”

“Enough,” Grant whispered.

“We will stop,” Marcus said, sliding the rest of the pages back together, “when you agree to the following: a rapid, uncontested divorce; a division of assets commensurate with your contributions versus Lorraine’s; coverage of Eli’s remaining expenses; and a confidentiality clause that protects you from the public spectacle your conduct would inspire.”

Grant stared at the tablecloth as if counting its threads. Under it, his feet twitched like a runner on a starting block who finally, begrudgingly, realizes he’s been aiming the wrong direction.

“Or,” Marcus continued, “we can take this to court and attach every receipt. Given the evidence—and the dates—no judge will care about your late-breaking midlife epiphany about ‘being happy.’”

“Don’t do this,” Grant said to me, and for a flicker his voice was almost the boy I’d married—hopeful enough to break something, earnest enough to make me hate my own softness. “We can—Lorraine, I’m sorry. I lost my way. Let me fix this.”

“Fix?” My voice was calm and steady, but for a new reason now: the phase where women apologize for being angry had finally passed for me. “Fix the part where you planned to run away from your life on my son’s birthday? Fix the part where you used our money on hotel shampoos and room service chocolate? Fix the cabin you built for two in your head? I don’t want your belated remorse, Grant. I want my life back.”

Clara let out a small, keening sound that wasn’t pretty at all. For the first time, she looked like a person rather than a plot device. I felt a flash of something complicated and surprising for her—a kind of pity you feel for a deadly animal that doesn’t know why it keeps running into glass.

Grant’s shoulders collapsed an inch. Eli leaned forward, knotted his hands together on the table the way I do when I am determined not to shake. He had brought his nearly grown-up face to this dinner to see that an adult can break and survive. I owed him the ending where his mother does not blink.

“Sign,” I said.

Marcus slid the papers and a pen across the table. Grant stared at the signature line as if it were a cliff edge. Then, like a man who has been falling for longer than he realized, he stopped resisting gravity and signed. Clara began to cry in earnest. Eli exhaled so quietly I felt it more than heard it.

“Thank you,” I said to Marcus when the front door finally closed behind our guests. “For everything.”

“You did the hard part,” he said. “You told the truth out loud.”

After he left, I washed the wineglasses one by one, the soothing banality of hot water and soap a counter-spell to the last two hours. Eli took over after a minute and pressed me down into a chair, then crouched and wrapped his long arms around me.

“We’re okay, Mom,” he whispered into my shoulder. “We are so okay.”

I believed him.

We left for Italy two weeks later, the papers filed and the ink dry enough to not smear. Tuscany is a cliché until it becomes your life for a little while—the hills more a color than a shape, the town squares blooming with elderly men arguing about nothing in particular, the afternoons that taste like rosemary and heat and the sudden relief of shade.

On the terrace of our little rented villa, Eli and I played endless games of gin rummy with gelato spoons and talked about what to pack for his dorm room and whether he thought in math the way I think in sentences. I slept ten hours a night. I read an entire novel in a hammock while bees made the lavender hum. Grant’s lawyer sent the final decree; Marcus forwarded it with a note that read simply Onward.

By the third week, the altered horizon inside me felt less like a violation and more like my own design. My life had not exploded; it had unfolded a different direction. It is a trick of perspective: destruction from one angle, renovation from another.

On our last evening, Eli and I walked down into town for dinner, arm in arm. The cobblestones forced us to slow; all good things do eventually. In the piazza, a little girl chased pigeons and shrieked with joy when one lifted, comic and indignant. Somewhere, someone played a battered accordion and made it sound like a cathedral.

“Thank you,” Eli said suddenly.

“For what?”

“For not letting him rewrite our story,” he said. “For choosing us.”

“I always will,” I said, surprising neither of us.

He looked toward the restaurant at the far end of the square. “Come on,” he said, tugging my hand. “Your pistachio gelato is melting.”

We crossed the square. The church bell tolled the hour. A campus at the other end of the world waited patiently for my son to arrive. My own rooms waited in a quiet Oregon house that was mine again not just legally but spiritually. The last flakes of rage settled somewhere I could live with, like dust in a new room that I knew, finally, how to clean.

And when the waiter handed me a menu and called me Signora like I had always belonged there, I ordered without asking anyone else what they wanted.

Part Two

Back home, ordinary beauty met me at the door: the prickly welcome of a houseplant I’d managed not to kill, the dry, frank smell of wood and paper, a stack of mail that contained precisely nothing explosive. The silence felt real this time, not like empty space after a slammed door.

Marcus’s final email arrived with attachments like little flags of surrender. Grant had resigned from his company the previous week, “to focus on personal matters,” the press release said. The settlement read like justice measured out in dollars and signatures: 70 percent of marital assets to me, continued coverage of Eli’s college costs, an apology letter I would never be forced to read and never be able to forget. He moved out of the river house quietly. Clara’s Instagram turned the kind of private in which people still see but pretend not to.

I sold the Hublot.

The weeks that followed were not cinematic. There were no dramatic speeches at dawn or community standing ovations. There was me at my kitchen table with a yellow legal pad, writing lists of practical things that a new life requires: car maintenance, health insurance, a small herb garden for when the weather turned honest again. There was Eli packing damp-shouldered cardboard boxes for a dorm in another state and pretending he didn’t see me wipe a tear on my wrist. There were three afternoons spent changing every password on everything.

There was also the slow surprising bloom of capacity. With my brain freed from the contortion of rationalizing someone else’s absence, I could think about making something of my own. The math that had always snaked softly through my days—flows of people and time, input and output, optimization under constraint—pressed more urgently against the inside of my ribs.

Jasmine, who had never been wrong about any important thing in her life, said it plain: “You built a system that made other people rich. Build one for yourself now.”

I did. I called it Lighthouse. It started as a re-skin of the property-management platform I’d designed for Grant’s firm—rewritten from first principles both to honor my new lawyer’s advice and because it turns out a broken heart makes you an obsessive refactorer. I built the bones in six weeks of destructive joy and then called three other women who had been told “good girl” too often and “yes, CTO” too rarely. We rented a small office above a consignment shop that smelled like cedar and ambition and ordered used desks off Craigslist.

It felt like falling in love with the right person for once.

Lighthouse did not change the world. It changed ours, which was enough. It signed its first paying client in a month and broke even in three. At our first team lunch, we ordered Thai food and typed with napkins tucked into our collars, laughing like women at a sleepover. The bank account grew a small, even, respectable line. Every time I paid an invoice to another woman, something in me that had been stuck since my twenties clicked another notch into place.

The day Eli left for college, I drove him to the airport at four in the morning because that is the hour you choose when letting go feels sacred. He hugged me with those long arms he’d grown when I wasn’t looking, and I smelled a future in his hair that wouldn’t require me to hold it steady for him. “Text me when you land,” I said, then shook my head. “No. Don’t text me while you’re landing. Text me when you’re done landing.”

He laughed, rolled his eyes the way a good son does so his mother knows she’s silly and loved, picked up his bag, and did not look back because that is how bravery works sometimes. My heart broke and healed in one motion—like the rib that has to reset around a clean cut.

When I got home, the house felt briefly like a too-large coat. I made coffee and took it to the back step. Neighbors’ sprinklers ticked like patient clocks. The early light lay flat and wide, the way mornings do when you’re not rushing anyone to first period.

My phone buzzed. It was a number I hadn’t saved because sometimes the person you were with becomes the person you write “unknown number” over in your head.

“Lorraine,” Grant said when I answered. “I…wondered if you’d—if we could—”

“You don’t sound like a man who knows what he’s calling for,” I said, not unkindly.

He let out a breath. “I wanted to apologize. Not the legal apology. The human one.”

“Okay,” I said.

“I was cruel,” he said. “And selfish. And arrogant. I let work become a god and you became altar supplies. I told myself stories I knew weren’t true because the truth made me feel small.”

I listened to the heat pop on the sidewalk. “Thank you,” I said. “That’s the apology.”

He laughed once, without humor. “You don’t have anything you want to say back?”

“I have so much I could say,” I said. “I have a book’s worth. But I’m choosing what I say to myself instead.”

He was silent for a moment. “Eli?”

“Is fine,” I said. “Because I am.”

“Good,” he said, and I believed he meant it. We hung up.

It is a particular relief to accept that closure is sometimes simply the door that closes, quietly, at the end of the hall.

A year to the day after that dinner at Evergreen, Marcus and Jasmine conspired to throw us a small non-party at Evergreen’s upstairs room. The group consisted of four women who kept our company alive on nothing but Ruby on Rails and iced coffee, Marcus with a bottle of something celebratory, and Eli on FaceTime propped against a candle so we could all pretend he’d come home for the weekend.

Jasmine toasted first. “To the woman who rebuilt her life from the bottom up,” she said, eyes bright, smile easy. “And to the son who learned from her that love is a verb not a promise.”

“To a lawyer who knows when to be a friend,” I added.

“To gelato in foreign cities,” Eli said from the phone, grinning.

“To a future with no surveillance of anyone else’s napkin,” I said last, earning half a dozen laughs.

When the glasses had emptied and the night thinned to the hour when even restaurants get sleepy, I walked home along the river because some things are worth moving slowly for. The city leaned against the water like a person finally allowed to rest. The lights dragged long bright fingernails across the surface. It was unseasonably warm; a man in a t-shirt jogged past me with headphones like small moons. On the Hawthorne, cyclists rattled like coins in a good pocket.

At the corner of my street, I paused and looked up at the window that was mine. The Tupperware I’d left on the ledge after repotting the basil had blown over; I would pick it up in the morning. I could see the edge of the new bookshelf in the front room, books in stacks that only I would ever have to justify. On the kitchen table, a manila folder sat with Lighthouse’s federal trademark application signed and ready to mail.

People ask sometimes—when you start over this publicly, strangers feel it’s their business—whether I would do anything differently. I always give the same answer because it is the truest thing I know: I would have listened sooner. Not to him. To myself. The little voice that said nothing about the way I was living felt like me. The bigger voice that demanded I keep breathing smaller to make someone else bigger—that voice had practiced so long I mistook it for truth.

Now, when I hear a voice, I ask it who it’s trying to save.

That winter, Eli came home with a girl who had a laugh like a bell and a major in something beautiful and unrealistic. He washed his own dishes without being asked, and I forgave him for not wiping the counters well. We made cinnamon rolls and burned the first batch. He hugged me at the stove like a child for a second and then pretended he hadn’t. I turned and hugged him back and pretended I hadn’t either.

On the first truly sunny day of spring, I planted rosemary in the little bed by the fence. Two streets over, someone’s new baby cried with admirable volume. The neighbor’s dog carried a stick that was absolutely too big and absolutely correct for his size. My phone buzzed with a new client inquiry. I wiped my hands on my jeans and answered. Work felt like the good kind of hard: the kind where you end the day pleasantly tired and believing that tomorrow will be an honest repeat.

In the mailbox that afternoon, I found a thin envelope with no return address and my name typed the old-fashioned way. Inside was a single sheet.

I never deserved you, it read in the precise, careful handwriting I’d once thought was charming. But I learned from you how to be braver with the truth. Thank you. —G.

I folded it back into its envelope and put it in the drawer where I keep translations of foreign recipes and the jewelry my grandmother wore on her wedding day. Not because I intended to read it again, but because it deserved not to be thrown away in a moment of performative freedom. The past shouldn’t be litter; it should be compost.

That night I sat on the back steps with a cup of tea and watched the color drain from the sky like a city-wide exhale. The rosemary breathed pepper into the damp air. A bicycle bell chimed two streets over. Somewhere, a couple fought quietly in a kitchen they would both love again in three days.

Grant’s words from that first awful night flashed across my mind—the way he had said “ditch the child support” like the phrase tasted exciting—and I realized that the line had lost all its power. It had been nothing more than a costume jewel in a bad script. The real story had turned on a different sentence altogether, the one I had finally given myself permission to say:

No.

No to the wrong kind of silence. No to the corrosive apology. No to the table that asked me to set it and then expected me not to eat. No to the life that required me to shrink to make someone else’s dream fit.

And yes—this is the important part—to the new sentences that followed: Yes to my work. Yes to my son’s laughter in another state. Yes to coffee on the back steps and code that works the first time and jasmine at the restaurant bar and Marcus’s dry humor and the smell of rosemary at dusk.

Because in the end, the story I tell myself is the only one I can be sure I get to write. And mine, as it turns out, is a love story after all—about a woman who chose herself, and a boy who learned from her that courage may break your heart but never your future.

The last light let go of the fence. I carried my empty cup inside, turned off the lamp, and left the window open so I could hear the night.

END!

News

Airport Security Dog Wouldn’t Stop Barking at a Pregnant Woman — Then Everyone Learned the Heartwarming Truth. ch2

The winter morning at Brighton International Airport had been humming along in its usual way — rolling suitcases clicking over the tile,…

“My Mommy Won’t Wake Up…” — The Cry at the Airport That Sent a K9 Officer Racing Against Time. CH2

The airport was unusually quiet that Sunday morning. Officer Janet Miller adjusted her duty belt as she and her K9…

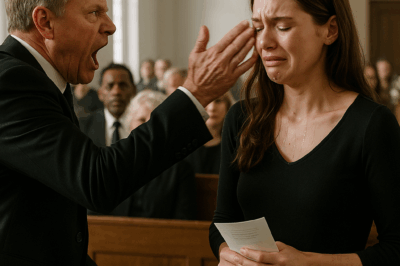

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”— So I Chose Revenge. CH2

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me and Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”—So I Chose Revenge Part…

My Brother Kicked Me Out After My Divorce, So I Prepared an Unexpected Surprise. ch2

Part 1: An Unexpected Betrayal I stood in my brother’s marble-floored foyer surrounded by moving boxes and the remnants of…

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

Jeanine Pirro and Tyrus Declare War on CBS, NBC, and ABC—With $2 Billion Backing, Fox News Makes Its Move. ch2

In a shocking move, Jeanine Pirro has declared war on CBS, NBC, and ABC, and she’s not doing it alone….

End of content

No more pages to load