My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!”

Part One

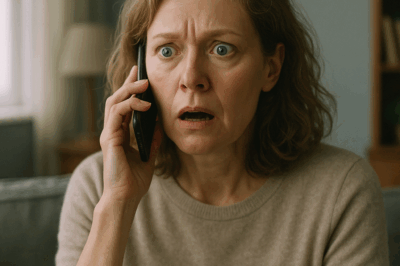

It was the kind of summer day that turns suit fabric into sandpaper. The AC in our office had given up making promises and was simply pushing warm air around. I’d finished my afternoon rounds, rolled my sleeves to my elbows, and was halfway through a progress report when the phone on my desk began to dance.

“Olivia.” The voice was a sob dragged across gravel. My mother-in-law. “Olivia—are you sitting? It’s—Liam—he—he had an accident.”

Everything in me went quiet, the way a house goes silent when the power trips. “What hospital?”

By the time I got there, the fluorescent lights had done to my face what they do to all faces—washed them of color and context. A nurse led me into a small, too-bright room where someone had painted a pastoral print on the far wall as if pretending the outside world were in here could help. Liam lay on the bed as still and composed as a statue, his lashes so dark against his skin they looked drawn on. My mother-in-law was hunched in a plastic chair, keening softly. My father-in-law stood behind her, his palm on her shoulder, staring at a spot on the floor that must have been the last place his dignity could stand.

“They said he—he pushed a boy out of the way at the crossing,” my father-in-law said, voice chipped. “The child was hurt. But not badly. He—” He gestured at Liam with the helplessness of a man who has always used his hands for fixing things and found them suddenly useless.

I sat. I reached out and touched Liam’s forearm. It was colder than forearms are supposed to be. I tried to fit the word accident around the shape of him and failed. My lungs took my breath like a toll.

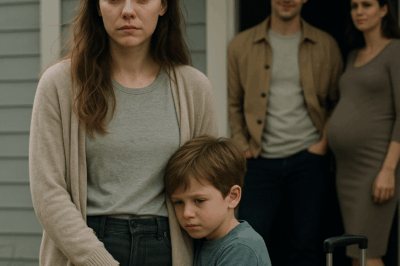

The days between the call and the funeral were a collection of tasks I didn’t know how to do but did anyway because doing is the only bridge over shock. I called people whose numbers I remembered because they had been on the fridge in a different apartment four years ago. I agreed to flower arrangements and music and said yes to sandwiches I wouldn’t eat. Liam’s colleagues sent messages full of adjectives—bright, reliable, decent. Old classmates texted headlines and emojis and then, when I didn’t respond, sent actual sentences, and eventually they showed up with the awkwardness shared grief demands: hugs that don’t know how long to last, silence that isn’t empty but isn’t full either.

As we stood in the cool hush of the funeral hall, people filed past with faces that had belonged to my twenties and had aged with mine: colleagues, a neighbor who used to borrow our drill, a coffee shop barista who remembered that Liam always asked for the extra stamp on his loyalty card if I wasn’t with him. My mother-in-law, who is normally sunshine personified—shopping trips, soups on your porch when you sniffle, jokes told badly but with gusto—looked like she had been erased and redrawn.

The service itself was simple because he had been simple in the best ways: a short eulogy, a favorite song (the one he’d turned up too loud in the kitchen while cooking on Sundays until I laughed and made him turn it down), the kind of memories you can only offer when the person in them hasn’t complicated their arc with lies.

It was almost done when the doors at the back pushed open and a woman walked in with the brisk entitlement of someone who never waits for her name to be called. She was plump, her brown hair curled into ringlets that framed a face I did not recognize. There was a pale pink ribbon pinned to her tote—the maternity mark the city gives out—which she tapped as if it were a badge that could conjure respect.

She walked straight up the aisle, past the mourners who stiffened as she brushed them, and came to stand within arm’s reach. She placed her hand on her stomach, lifted her chin, and said, voice pitched to carry, “I’m pregnant with his child. I’ll be taking the inheritance.”

For a second, the room made no sound at all, as if everyone present had inhaled in perfect unison and then forgotten how to exhale.

I blinked. It was so absurd I couldn’t find the pocket where words are kept. My gaze fell, unbidden, to the hand on her belly. It was a theatrical gesture—an actress’s imitation of care. Something hot in me, something I didn’t have a name for yet, flared.

“Please leave,” I said, finally, because grief had not yet made philosopher of me. It had, however, made a bouncer.

“She’s carrying my son’s child?” my mother-in-law’s voice cut in, chopping the sentence the way her knife chops carrots when she’s angry. I looked at her and saw, superimposed over the woman who had taught me her recipe for chicken and rice and the best way to get coffee rings off wood, a stranger: cold, steel-bright, unflinching.

“You,” my mother-in-law said, taking a step forward, “used to stalk Liam. You left letters on our porch when he was in high school, and I had to walk you to the curb and ask you to leave. You’re five years older than he was. You handed him gifts wrapped in paper like we didn’t know what giving means.” She flicked her eyes to the pink ribbon and back. “You always were dramatic.”

“How rude,” the woman bristled. “Look at this.” She tapped the maternity mark again and jutted her chin toward her tote, as if the sticker meant more than trust.

“You get those at the clinic when you’re actually pregnant,” my mother-in-law shot back. “You can also find one online for free.”

“This is his child,” the woman said, louder, in case anyone had missed the performance the first time.

“It is not,” my mother-in-law said, and then she did the kindest thing anyone did for me that week: she turned to an usher and said, “Please show this person out,” and the usher, who had been waiting his whole life to be given a clear instruction in a gray area, did exactly that.

The woman planted her feet for a second, looking like she might try a speech. But two ushers materialized, one on each side, and as they guided her away, she snapped, “I’ll come back!”

After, at my in-laws’ house, the living room full of casseroles from neighbors and hands that didn’t know what to do, the intercom buzzed. My father-in-law went to the monitor, and his mouth tightened. It was her. Again.

“Hey,” she said, voice scratchy through the speaker. “How much inheritance does he have? Can I at least have what’s on hand? Give it to me quickly.”

My mother-in-law and I looked at each other. Something in the absurdity snapped a thread: I began to feel anger, hot and helpful.

“Who are you?” I asked into the speaker, surprised at the calm in my voice. “What is your relationship with my husband?”

“Liam and I have been in love for years,” she said. “We’re soulmates.”

“Do you have evidence?” I asked. “Are you saying he cheated on me, while married?”

“Don’t call it cheating. We’ve been in love all along,” she said, and she held up her phone to the camera to show a photograph of Liam that I recognized instantly—it was one he had posted to his own social media two winters ago, the day he bought a new beanie and pretended to hate how much he liked it.

“Did you take that?” I asked.

“He posted it,” she said, defensive. “So what?”

“So you’re using his public photos as your private proof,” I said. “Got it.”

Something Liam had mentioned floated back to me, a silly thing, dismissed at the time: “A strange woman at the station said we’d met, but I couldn’t place her,” he’d said one evening while rinsing dishes. “Dyed brown hair, curls, maternity badge… it made no sense.” The description sat now like a puzzle piece that fit too well.

I felt my mother-in-law looking at me. “You’re not a mistress,” I said into the intercom, the words coming out flat and clean. “You’re a stalker.”

“I’m not,” she hissed. “Look at my belly.”

“It’s not a crime to be overweight,” my mother-in-law said, voice so sharp she could have cut a thread with it.

“If you’re pregnant with Liam’s child,” I said, “then bring a maternity record book. Bring a test result from a clinic with his name on it. Bring anything but a sticker you can get off Etsy.”

“I don’t— You’ll see it when the baby’s born,” she sputtered. “He’ll look just like him.”

“People say that about most babies who aren’t theirs,” I said. “You can say it to your mirror if you like. It isn’t evidence.”

She glared at the camera. “I’ll come back,” she said again, as if repetition could turn threat into promise.

We called the police. They were kind, brisk, and practical. “If she returns,” the officer said, “call immediately. Don’t open the door. Document everything.”

I returned home at dusk with the fatigue that only comes after you’ve been surprised by more than one kind of cruelty in a single day. Grief is physical; it lives in your back and your jaw and your scalp. I opened drawers just to close them, to remind myself that there were still things in my control. I bagged up some of Liam’s sweaters to donate and then, ashamed of my own efficient betrayal of his presence, took them back out and folded them again on the bed the way I used to.

I went outside because sunlight can be a prescription. I walked two blocks and turned right, the habit of years, and there she was, like a bad punchline, standing near the corner with that smug hand on that theater-belly. “Ready to hand over the inheritance?” she said.

“Listen,” I said, and something in me, hitherto patient, snapped into hard clarity. “Stop saying the word inheritance like it is a key to a locked door. It has nothing to do with you. If you don’t know who the father of your child is, go look somewhere else. Liam is not it.”

“You don’t believe me?” she sneered. “Look at this.” She thrust her phone toward me. The photo on the screen showed a right hand resting on a belly. There was, indeed, a bracelet on the wrist—a simple leather band like the one Liam wore sometimes on weekends.

I took the phone and zoomed in. The person who took the picture had hidden the angle badly; the fingers in the frame were thicker than Liam’s, the knuckles knobbier. There was a small mole on the back of Liam’s hand, the size of a grain of rice. The hand in the picture didn’t have it.

“That bracelet,” I said, handing her the phone, “is cheap. You can buy it at the mall. The hand is not Liam’s. He has a mole. See? No mole.”

She faltered, her bravado deflating, then regrouped. “Once he’s born, you’ll see,” she said stubbornly. “You’ll be a grandmother, and you don’t even know it.”

“If you are pregnant, which I doubt,” I said, because suddenly I did, “you should go home and rest. You shouldn’t be out here hustling in the sun for a payout.”

She pulled the pink badge from her tote like she was playing a trump card. “This is proof,” she said.

“It’s a sticker,” I said. “You can print one out on the internet. You can wear a fake badge for clout, but you shouldn’t. You cheapen a thing some women wear because pregnancy makes us invisible in other ways and this helps strangers see us.”

“You haven’t even been married long,” she spat. “You don’t know everything about him.”

“He mentioned you once,” I said. “He said a woman approached him at the station and asked if he remembered her. He didn’t. That woman was you. He remembered a feeling, not a face. That’s not romance. That’s a warning.”

She stared at me, mouth a flat line, then whirled and marched away without even the decency to waddle if she was going to pretend the belly was the point.

“You will not show up at my husband’s funeral again,” I called after her. “And if you are not pregnant, do not borrow people’s pity to make yourself feel like a main character.”

I stood there a long minute after she turned the corner, my hands shaking because families are held together by the smallest gestures and sometimes the smallest lies do the most damage.

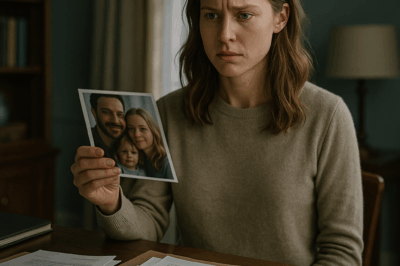

Back home, sorting Liam’s things, I found a small envelope tucked into the bottom drawer of his bedside table, the one that used to hold his terrible bedtime socks. The date on the front was next month—our anniversary. Inside was a letter, written the way he writes—slowly, sincerely, without irony. He had thanked me for something small, for laughing at a joke I had heard him tell badly a hundred times, for making the house feel like a place where he could be soft. He had written, “I love you in the ordinary ways, and that, I think, is the miracle.” I held the paper and cried like people do when they have been strong in public and allowed themselves to be exact in private.

A week later, I went to my obstetrician because grief had odd effects on my body and kindness told me to check. I expected the doctor to say stress and time. He said pregnant.

I blinked at the screen. A tiny grain of rice pulsed in the middle of the black. I laughed then—wildly, softly—because the last time my husband had seen a grain-of-rice sized thing on a screen it had been his mole in a picture meant as a lie. I put my hand on my belly and thought of words that had been used against me now returning as a promise.

I drove to the cemetery and sat on the grass and told Liam that he had left me miracles in multiple forms: a letter, a child, a community that turned up when I could not. In the months that followed, I carried the baby through nights where I woke sobbing without knowing why and days where I forgot I could laugh and did. My mother-in-law knitted booties like she was being paid in amnesty; my father-in-law learned how to make pancakes the way Liam had so he could feed me when I was too tired to chew. The boy Liam had pushed out of the way of the car—now healed, now a teenager with a patched-up bravery of his own—came with his parents to say thank you and called my son “little brother” and made me cry sitting straight up at the kitchen table.

Three months after my son was born and named for a man who would never hold him, the police called to tell me the woman who had burst into my life had been arrested. Stalking, fraud, a string of small cruelties that had finally snagged on someone else’s courage. I felt nothing but relief and a kind of tired pity—not because she deserved it, but because what a small life she had been living, to think attention, even negative, is better than the hard work of being loved.

Part Two

Grief, when fed, changes shape. The sharpness dulls. What remains is an outline inside you of the person who has gone and the person their leaving made you become. For me, the outline is a kitchen at five in the morning, light low, a kettle shrilling, a little boy wriggling on my shoulder while I make coffee with one hand. It’s my son’s laugh—Liam’s laugh—echoing off the pictures in the hallway, where I have hung a photo of his father as a boy, almost as if the two of them, separated by decades and DNA, could giggle to each other through glass.

By spring, I had returned to work part-time. The school let me teach two sections of literature and one of composition, and my classes learned quickly that assignments are self-care if you use them right and that sometimes a paragraph can hold more of a person than a photograph. I took a paper map out of my desk drawer and showed them how lines like roads can be sentences if you navigate them carefully. “Write me your street,” I told them one day. “Write me your kitchen table. Write me your grandmother’s hands.”

The community that had surrounded us in crisis stayed. My neighbor across the hall, a gentle man with the most aggressive ficus you’ve ever seen, installed a hook by my door so I could hang the diaper bag without dropping my keys. My father-in-law brought oranges when the baby got his first cold because he remembers remedies the internet forgot. The family of the boy Liam had saved invited us to their barbeque and handed me a plate before I could say no out of some misguided allegiance to sadness, and I ate charred corn and let the sun tell me that life has room for more than one kind of brightness.

I took the letter out sometimes, the one meant for an anniversary that never came, and read it on the sofa while my son napped. He looked just like Liam when he slept—the same crease between the eyebrows that made him look perpetually concerned even when dreaming of simple things. “I am raising him with you,” I would say out loud, to the empty room that wasn’t empty anymore because houses remember. “You’ll be louder in him than silence.”

As for the inheritance—such as it was—it turned out Liam had been quietly better at money than either of us guessed. He had dabbled in stocks in the timid way younger men who grew up watched their fathers lose savings sometimes do—carefully, with embarrassment. There were modest holdings I’d only learn about because I had to go through a file marked Receipts and stop often to cry and then start again. My lawyer helped me make sensible decisions. We didn’t buy a bigger place, or a car with features whose names sounded like weapons. We got a savings plan and a college fund and a certificate for rainy days because grief is a weather pattern you don’t need an app to predict anymore.

The woman stayed gone because the law told her to. The sting of her presence faded. My mother-in-law sometimes says, over her tea, “What a creature,” with the kind of dismissive power only older women who have seen worse can wield. I nod. Then we change the subject because our lives are much more interesting.

At the end of the school year, I brought my son to the last period of my literature class—his grandmother had to go to the dentist, and my father-in-law’s car was in the shop, and life is just logistics sometimes. He cooed at my students, who immediately placed him at the center of their collective heart. “He looks like the guy in that photo,” one boy said, pointing to the picture on my desk of Liam at 25 wearing the beanie he had defended like it was a member of the family.

“He does,” I said, and I didn’t break.

After class, a girl who hadn’t said much all year lingered by my desk. “Ms. D,” she said, shy. “I—my mom’s friend had someone show up at a funeral and say something like—that thing that happened at yours.” She looked me dead in the eyes the way only sixteen-year-olds and saints can. “You pressed charges. Right?”

“Yes,” I said. “Not that day. Later. When I had a name, and a paper, and the strength.”

She nodded. “Good,” she said. Then she took a breath and let out a story she’d been holding like a weight. I listened. When she finished, I told her the number for a counselor and the truth about lies: they are quick like mice; they run in corners and live off crumbs. Honesty is slower. It walks upright. It eats at the table. It stays.

On the anniversary of Liam’s death, we drove to the cemetery with flowers that my son tried to eat and my mother-in-law gently redirected. We told stories. We cried. We laughed. We did the thing families do when they make peace with a void: we stood at the edge of it and talked across, loudly, daring it to interrupt. The boy Liam saved came too, with a lopsided grin and a scar you’d miss if you didn’t know to look. He lifted my son under the arms and said, “Looks like I got the little brother I wanted.” I could have kissed him for that.

There are days—because life is generous with them—where being a single mother feels like being a circus performer in a tent that caught fire. And there are days where it feels like the easiest thing I’ve ever done because it’s the truest. When my son brings me a feather from the park and says “bird,” it is a kind of catechism. When he points at Liam’s photo and babbles, I tell him the story again: of a man who danced badly but enthusiastically, who made soup on Sundays, who once saved a boy because he could, and in doing so saved us too in the way that stories save: by giving us something to belong to.

Sometimes, on my walk home from school, I think of that hot day in the office when the phone rang and my life split into before and after. I think of a stranger marching down the aisle and stealing attention and trying to steal meaning. I think of how grief and anger braided themselves into a rope sturdy enough to hang on to until the river slowed. I think of the letter in my bedside table and the tiny smile that curls my mouth every time I open it because love, it turns out, behaves like light—it lingers even after the source has gone.

I do not imagine Liam watching us. I do not need to. He is here in the ways that matter: in the sound of my son’s laugh, in the way my mother-in-law soaps the casserole dish, in the tilt of my father-in-law’s head when he reads the newspaper out loud as if the world deserves witnesses.

As for the woman, sometimes I catch a headline about stalking arrests and scan it out of old habit. If I see her name, I will not read further. If I don’t, I won’t search. I have said what I needed to say. I have chosen a life that does not include her. That is the best ending—for me, for my son, for the part of me that survived.

I once considered moving out of this apartment when the memories pressed on me like a too-warm shirt. Now, the walls carry the echo of a small boy’s delight and the occasional scream and the constant narration of things he thinks I can’t see—“MAMA BIRD, MAMA CAR, MAMA DOG.” It’s chaos. It’s joy. It’s ordinary. It’s ours.

People ask, sometimes, mostly students who haven’t learned yet that it’s okay not to be curious about everything: “Do you think he’s watching you?” They mean Liam. They mean heaven. They mean forgiveness. I say, “I think he’s in the stories we tell and the promises we keep.” I say, “I promised him I’d be strong.” I look at my son, sticky with jam and righteous with toddlerhood, and I think: Promise kept.

END!

News

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls ‘Help with the Funeral!’ Me – ‘My MIL died 3 years ago’. CH2

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls “Help with the Funeral!” Me — “My MIL died 3 years ago.” Part…

End of content

No more pages to load