My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One

Part One

The night it broke began with a small cruelty made large by an audience. Leo never did anything small if someone might clap.

We had been the last to leave a restaurant that had once been ours—back when we could sit at the window and make up stories about the strangers walking by, when dessert tasted like we’d earned it instead of owed it. It was late and the rain was coming down in sheets so fine they looked like smoke, the streetlights turning the whole block into a stage set made of water.

“Keys,” Leo said, hand out, palm up, voice velvet over code. He wanted to drive my car. He liked the way it fit him, liked to talk about torque to men whose watches cost more than his first paycheck, liked to drift it into the valet like a tailored suit sliding onto a hanger.

I put the keys in his palm. It’s funny how long habits can feel like love.

Halfway to the curb, I realized my tote bag—phone, wallet, everything—was still on the back of my chair. “Wait,” I said, turning. But Leo had already clicked the fob and glimpsed his reflection in the rain-slick window. He liked what he saw looking back.

“I’ll be a minute,” I called over my shoulder to the hostess as I trotted back in, leaving a wet constellation on the tiles.

When I returned, bag hugged to my chest, Leo tapped the roof once (superstition in a man who didn’t believe in anything but himself), then slid into the driver’s seat. He didn’t unlock my door.

“Let me in,” I said through the crack in the window. I kept my voice even. Even is how you survive a thousand paper cuts without bleeding out.

He smiled without using his eyes, a demo version of pleasure. “We teach lessons, Rachel.”

Thunder hit somewhere far off, a man clapping sarcastically in the dark. “What lesson is that?”

“That you don’t make me wait.”

There were at least six answers to that, all of them corrosive, some of them accurate, none of them useful. The hostess was at the bar pretending not to watch. A couple in good shoes stood near the awning, their Uber delayed by a lattice of red brake lights. Someone across the street raised a phone—our life’s subtitle always a new recording.

“Unlock the door,” I said. It wasn’t a request. It felt—finally—like a sentence.

He put the car in drive, the purr of the engine obscene under the rain. “Call me when you’re ready to apologize for your attitude.”

“My phone is in the car.”

He lifted it between two fingers like bait, smiled, and then he drove away, the backwash baptizing me in humiliation I refused to let turn to tears. He made the left in a clean sweep like cruelty was choreography.

I stood there with water tick-ticking off my hair into my eyes. A man under the awning shook his head. The woman with him touched her throat the way people do when they witness a bruise blooming and can’t decide whether to look away or memorize the color.

A black sedan slid to the curb in a line so straight it could have been drawn with a ruler. The window lowered. James.

The first time my father insisted I hire a security professional after Leo’s “joke” on the remote trail, I called him dramatic. My father, who made spreadsheets for vacations and carried a first aid kit on walks, had put his reading glasses on and said, very evenly, “A man who jokes about leaving his wife might one day forget the punchline is supposed to be laughter.”

James had been waiting near enough to hear, far enough to keep the illusion of privacy intact. That’s what the good ones do; they give you the dignity of invisibility until you need the dignity of protection.

“Get in,” he said now, voice low, not unkind. He didn’t offer pity. He offered a door and heat. I slid in, the seat hot through my dress, a shock of comfort that made the cold more acute.

He handed me a blanket that looked like it had been refolded a thousand times. There’s a language people who do careful work speak with things: a blanket with square corners, a thermos that doesn’t dent, a spare phone charged to eighty percent. James spoke that language fluently.

We didn’t talk until the rain gentled from punishment to noise. The city moved past like a watercolor left out on a lawn.

“He locked you out of your home last time,” James said at the light, not a question.

“Two hours at Morgan Ridge,” I said. “No cell reception. Thunderstorm. He said I was being dramatic when I told him about the lightning. A park ranger found me.”

“Does he know where the deadbolt plates are in your house?” James said.

“How would he—” I started, then stopped. Leo’s golf buddy ran a home automation company, the kind that installs locks you can open with a grin and a phone. Leo was on the board of three charities he didn’t care about. He knew the sommelier’s name and the sommelier’s divorce lawyer’s name. He knew the car valet’s favorite soccer team and tipped him in tickets. He always found the people who could make a rule soft and bought them a nice dinner.

James didn’t need my answer. “I’ll check the back study window.”

When we reached the house, it looked like the kind of home people draw when they’re pretending money is an aesthetic instead of a performance: clean lines, generous glass, a door the color of good espresso. It smelled dark. He wasn’t there.

There was an envelope taped to the wood like a spitball from a private school. When you’re ready to apologize for your attitude, call me. His handwriting looked like a slope pretending it was a straight line.

James took the note and turned it over as if the paper itself might whisper strategy. He tucked it into his jacket. “Back study window,” he said, and disappeared along the hedge line.

Somewhere a dog barked that hollow suburban bark that has never once scared anyone. I looked at my reflection: a woman whose spine had remembered itself. The lock clicked. James stood inside the open door, a silhouette in a house that suddenly looked like a place that never quite belonged to me.

On the kitchen island, my bag sat where it shouldn’t be, a glass of water sweating beside it, a napkin folded in a triangle, the angle too precise to be an accident. James didn’t reach for a light. “Don’t touch anything,” he said. “If he’s escalated to locking you out for sport, we document.”

“Do we call the police?” I asked. Even to my own ears, the question sounded like a child’s—a learned instinct to outsource consequences.

“We call them when we need to establish a paper trail. We call a lawyer now.”

“Miss Albright?” I said. The name came out of my mouth like it had been living behind my teeth.

He nodded. “And Rachel—change the locks. Tonight.”

“I’ll call a locksmith in the morning.”

James met my eyes, and for the first time since the rain started, I felt the floor of my life stop moving. “Tonight,” he said.

The next week, Leo came home with peonies and filet mignon and “you know I don’t think straight when I’m stressed,” and I ate dinner at our table with a knife that felt heavier in my hand than it had the week before. I smiled. I said the right lines. There is a kind of acting women learn under men like Leo that looks like grace because no one taught us how to call it strategy.

He mentioned an investor meeting I’d “missed,” a thing I would have rescheduled work and sleep around if I’d known. He grinned in the way of men who weaponize benevolence and said he wanted to “protect me from pressure.” He loved the story in which I was an orchid he watered. He loved it most when he locked me out of the greenhouse and then told the neighbors how delicate I was.

James came by that night under the auspices of checking the window lock. He had installed the new deadbolts himself. He had a drill that sounded like the opposite of the rain. He moved like a person who has made holes in walls in foreign countries while someone else held a flashlight. “You need a forensic if he’s playing with the business accounts,” he said while the new plate slid into place with a satisfying clunk.

“I’m not sure I can handle a forensic,” I said.

“You can handle a drill,” he said without looking up. “You can handle a forensic.”

Miss Albright had a law office with books that looked like they could hold up a roof. She read the postnup my father had insisted on with a highlighter that might as well have been a guillotine. “Good contract,” she said, almost to herself, like she was smelling bread to see if it was done. “Financial misconduct clause is very clear. You’re covered if we can show diversion of assets.”

“Diverted to where?” I asked.

Miss Albright smiled without friendliness. “That’s where James comes in.”

Years ago, I would have resisted. I would have wanted to believe Leo could be taught, almost as if my patience were a classroom he’d eventually be graded in. Now, the only lesson plan I wrote was for myself.

The first thing James did was not punch Leo in the throat, though I suspect the thought was not displeasing to him. The first thing he did was install a dash cam the size of a wedding band in Leo’s car and software that logged access to our shared accounts when Leo was at the gym telling strangers about his bench press. He became the ghost Leo couldn’t imagine existed because men like Leo don’t imagine anything they can’t see admiring them.

“What is a bodyguard, really?” Leo once asked a dinner guest, waving his fork at James like he was a butler in an old movie. “A gorilla with etiquette.”

James had not reacted then, which is its own form of violence. He reacts differently now: with forensic accountants and timelines and a drafter in Miss Albright’s office who has a printing press in her fingers.

The second thing James did was teach me how to look at numbers like maps and not like mysteries. “People think they’re complicated,” he said, outlining in blue pen on a legal pad. “Most of the time, they’re just hoping you won’t read them.”

I read them. I read them at 3 a.m. and at noon on Tuesdays when Leo was at “golf” and at dusk while the day forgot itself. I read them until the transfers weren’t sneaky; they were insulting.

Miss Albright assembled a file so heavy it bent the leather of her briefcase. “This will be public,” she said. “That’s part of the medicine.”

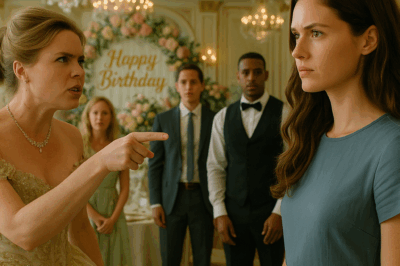

The timing presented itself like a stage hand pulling a curtain: Entrepreneur of the Year, tuxedos and a dais and Leo’s smile printed on programs, Leo asking me to wear navy because it made him look taller.

“I won’t miss it,” I said, and smiled like rain couldn’t touch me anymore.

The night of the gala, the ballroom looked like the inside of a watch: gold and glass, champagne the color of expensive time. Leo shook hands and layered compliments like bricks. Men laughed with their fronts and texted with their sides. Women in dresses the color of opinions hugged each other with one shoulder and analyzed each other with the other.

When the emcee called Leo’s name, he moved to the stage with the grace of a man who believed stairs admired him. He thanked the board and the investors and his personal trainer and me, “who keeps me grounded,” as if his cruelty were a helium balloon I held onto so he wouldn’t float into the ceiling. The room smiled. It always does for men who learn the choreography.

I stood because the spotlight asked me to. Then I moved because I had taught myself how.

“Speaking of support,” I said into the spare mic, the sound catching easily and multiplying across the room like startled birds. “I have some to show you.”

The screen behind Leo flickered. The logo evaporated. Numbers appeared, tidy in their shame. Transfers circled in red—James had picked the hexadecimal shade like a joke to himself, a color used in emergency exit signs.

“Over the last six months,” I said, “Mr. Hale moved funds into a private account labeled ‘consulting’ while privately consulting anyone but me.”

“We all move funds,” Leo said, too loudly, the mic still in his hand. The laugh he summoned died like a spark in damp grass.

“Of course,” I said. “But not like this.”

The audio played—the dash cam picking up his voice like he was bragging from inside a confession booth. Bleed it slowly, don’t spook the board. She’s too busy crying about rain to count. Laughter—the room’s, not his—was a sound with no humor in it at all.

“I believed, when you left me standing in a storm, that you were teaching me about my place,” I said. “You were. You just misidentified it. I run this company.”

“Rachel—” he started, and in the inch of silence between his voice and the next line of audio—I’ll leave her with nothing—James shifted from the wall and took up a place two feet from the nearest exit. He didn’t touch Leo. He didn’t need to. A lesson is more effective when it arrives with more options than a punch.

Miss Albright stepped onto the stage holding a folder that looked like a verdict. “Per the postnuptial agreement,” she said clearly into the mic Leo had lowered without realizing, “Mr. Hale is suspended pending a formal board review. The board has already voted to convene. Ms. Chin is hereby named acting CEO.”

Someone in the third row began clapping very quietly; other hands joined, uncertain, then confident, then loud. The applause didn’t feel like a coronation. It felt like relief. The board chair—who had made his fortune in wind turbines and therefore understood the conversion of pressure to power—stood to shake my hand.

Leo looked at James like a man might look at a locked door in a fire. “You think this is over?” he said, teeth bared in what he might have called a smile on a different night.

James looked down at him with the polite blankness of a hotel lobby, then said, “I don’t think about you at all.” He turned to me. “Your car’s out back.”

In the morning, the locks changed again. This time the click sounded like a home choosing me back.

Part Two

People assume the story ends when the villain is escorted out of the ballroom into the ache of his own consequences. That’s not wrong. It’s just incomplete. The end of a storm is not the beginning of the harvest, but you can smell dirt again, and that tells you where to put your hands.

The board’s emergency session the next day was thick with paper and light with patience. I brought coffee for the receptionist and shook hands for exactly as long as dignity requested. Miss Albright did not smile at anyone, which is, ironically, why people smiled at her.

“Ms. Chin,” the chair said, “your plan?”

“Build what makes money and burn what makes noise,” I said. “Also: no more consultants with the same last names as golf buddies.”

There is something deeply satisfying about the way a dozen people who once thought you were scenery now realize you’re the set designer. It isn’t vindication as much as it is calibration: everyone in the room moving their attention one click to the left where it belongs.

We put James on retainer not as a bodyguard but as a chief of protective operations, which is corporate for “man who knows where the exits are and keeps the fire extinguishers pressurized.” He started with the server room and the safe and then moved outward into the subtle perimeter we call habits: how often the night cleaning crew saw the CFO in the building, who had a second access card they didn’t tell anyone about, what the delivery driver’s route looked like at 2 a.m. and whether the person signing for packages is the same person every time. Leo used to treat James like furniture with a driver’s license. Watching the man who changed my locks replace policies that thought “trust” was a security protocol was—if you’ll forgive it—educational.

The divorce was not loud. That was by design. I did not want my life to become content. We filed quietly. The clerk who stamped the papers wore a tie with constellations on it and told me, “You’ll feel lighter than your own bones.” He was right.

Leo tried a few lines on the way down. You’ll never make it without me. Line folded into itself when the quarterly numbers came in higher than expected. The board will hate you. Line tripped over its own feet when the board voted unanimously to extend my contract. Everyone’s going to see you for what you are. Line evaporated when a reporter asked on the record, “What does it feel like to be in charge?” and I said, “Heavy some days. But my back is strong.” The photo that ran with the article made me look exactly like I felt: not happy, not triumphant—ready.

He violated the temporary restraining order once. James didn’t touch him. He met him at the curb with two uniformed officers who had been waiting, summons in pocket, paperwork in triplicate, a lesson with a letterhead. Leo shouted in the key of people who believe volume is a legal strategy. James tilted his head, bored. “This is the part,” he said dryly after the officers cuffed him, “where you learn to apologize to weather.”

It turns out “taught him a lesson” does not need fists. It needs boundaries enforced by consequences he cannot sweet-talk. It needs rooms where he is not welcome and doors he cannot open and faces that do not flinch but do not engage. It needs his name on a list not at a club but at a courthouse and my lawyer’s signature on a line under which his excuses do not fit.

My mother called twice that week. I did not answer the first time. I did, the second.

“You air our laundry,” she said. “You make him look bad.”

“He hung it in the rain,” I said. “I only turned on the light.”

“Your father and I didn’t raise you to be cruel,” she said, a line I suspect she practiced in the bathroom mirror.

“You didn’t raise me to be safe,” I said. “I’m doing that now.”

There was a pause in which she might have said I was right if she had been someone else. Then she said, “Are you eating?” Mothers, mercifully, cannot help themselves.

“Yes,” I said, and we found a channel we could both understand.

James taught me other things that didn’t feel like lessons until the moment I needed them. How to choose a table in a restaurant—back to the wall, eyes on exits, not a corner (you can’t move fast), not next to the kitchen (people who bring plates aren’t paid to break falls). How to enter a garage—mirror from the passenger side before you leave your car, keys between fingers not as a weapon but as a way to feel your hands. How to breathe when panic thinks it’s smarter than you—inhale four, hold four, exhale eight, repeat until the predator in your blood sits down and waits its turn to speak.

“Mostly,” he said one afternoon when he was teaching me what he called “civilian pattern recognition” (which sounded ridiculous until I realized I’d been doing it to bank statements for weeks), “you learn to trust the part of you that notices the frame is crooked.”

“The frame?” I said.

“You said once you could tell someone had been in your house because a picture was tilted. Most people would call that crazy. I call it your nervous system doing math. Listen to it. That’s your bodyguard. I’m just the guy in a cardigan.”

He did not wear a cardigan. He wore suits the color of fog and had a scar where his eyebrow gave up and started again. But he understood where comfort lives: not in the punch but in the plan.

I changed my phone number and didn’t publicize it. The old one turned into a voicemail box that James checked once a week like a trap he set for raccoons. It filled with apologies that sounded like invoices and fury that sounded like confessions. He forwarded anything useful to Miss Albright. He deleted the rest. “You don’t need to know every way a man can spell bitch,” he said, which made me laugh for the first time in longer than anyone should have to admit.

Work became a place where I could use the muscles I’d grown in privately. There’s a way the body remembers cold rain when you step into a boardroom; you can feel the damp in your bones, and then you can decide you have both hands on the umbrella now. I instituted quiet hours and loud accountability. I fired two consultants and promoted one receptionist who had ideas about scheduling that saved us enough money to make an old man on the board smile and say “margin” like it was an incantation. I wrote a memo titled We Do Not Hire Golf and taped it inside my desk drawer to make myself laugh on days I didn’t want to.

I saw James less and heard him more. He trained the building staff on drills; he taught my assistant how to deflect uninvited hands with a coffee tray without spilling; he did not linger at parties, and he killed rumors by being too boring to be interesting. “A good bodyguard is a vocabulary lesson,” he said once. “We change the way people speak to you because they learn new words for where the line is.”

On the one-year mark of the rain, I walked past the restaurant by choice. The hostess didn’t recognize me; I wasn’t wearing the kind of women’s raincoat men buy when they want to look like they support women who go to galleries. I wore a coat that could hold earbuds, a granola bar, and a key I didn’t have to hand over. It was drizzling, a friendly kind of wet. I stopped under the awning and watched a couple examine a menu as if the most important decision of their lives was pasta or fish. I hoped it was.

A woman inside held a wine glass the way people hold microphones. A man laughed with his body. It was all completely unimportant and therefore a miracle. You don’t know how good ordinary is until someone tries to convince you that ordinary is beneath you—and then leaves you in the rain to prove their thesis.

I walked home with a bag of fresh figs and a bunch of mint I had no plan for. I put the figs in a bowl I bought at a thrift store because old things that survived interest me more than new things that didn’t. I went to my door and turned my lock and listened to the click. It sounded like a period. That’s the punctuation you want on a story like this—not an exclamation point that startles you every time you pass it, not a question mark that invites him to rewrite the chapter. A period. Full stop.

People asked, in whispers that pretended they were simply curious, if James and I were—what exactly? An equation? A consolation prize? A romance written by a woman who has watched too many movies where the man who carries the umbrella gets the girl? We were what we needed to be: a boundary made human, a steady presence that turned a locked door from a threat into a promise. He didn’t save me. He kept the world quiet enough that I could.

The last lesson belonged to me. Leo taught it without meaning to, which is the only way he ever taught anything. He taught me that I do not need the storm to justify the shelter. I do not need to bleed to deserve the bandage. It’s obscene how long we are willing to be hurt if the apology arrives in a voice we love.

The evening it rained as if the sky had been holding its breath and finally allowed itself to gasp, I stood at my window and watched it pelt the glass with the fury of a thousand old insults. I made tea. I put the cup down on a coaster because my table is walnut and I respect what it used to be—tree, wild, older than me. I texted my father a photo of a lock and he replied with a thumbs-up because men of his generation think emoticons are contracts. I laughed and then I cried and then I laughed again, because systems hold and also you are allowed to be human in the systems you built.

I still keep a blanket folded in the trunk of my car. Blacks, wool, corners square. There are easier lessons to forget. This is one I will not.

When James texts me are you home, I reply yes and a photo of the figs and the mint and the lock and the tea and my bare feet on my own floor. He responds with a single word: Good.

It means lesson learned. Not by me. By the man who thinks weather is a punishment instead of a reminder that you are not in charge of the sky.

He can teach the rain all he wants. My door listens to me.

END!

News

My Father Gave My Inheritance to His New Wife’s Son, but the Truth Came Out at the Lawyer’s Office. CH2

My Father Gave My Inheritance to His New Wife’s Son, but the Truth Came Out at the Lawyer’s Office …

Bride Overhears Groom’s Shocking Betrayal, Returns to Wedding with Ultimate Revenge. CH2

Bride Overhears Groom’s Shocking Betrayal, Returns to Wedding with Ultimate Revenge Part One I didn’t plan to become the…

My Sister’s Birthday Cost 180k$…My Hotel. Seeing Me, She Said, ‘Kick This Homeless Person Out. CH2

My Sister’s Birthday Cost $180K… My Hotel. Seeing Me, She Said, “Kick This Homeless Person Out.” Part One It…

At breakfast, my husband threw coffee on my face when i refused to give my credit card… CH2

At breakfast, my husband threw coffee on my face when I refused to give my credit card… Part One…

At my wedding, my mother-in-law declared, “the child she’s carrying belongs to another man” CH2

At my wedding, my mother-in-law declared, “the child she’s carrying belongs to another man” Part One I can tell…

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” ch2

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” — So I… …

End of content

No more pages to load