My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on us

Part 1

My name is Violet, and I turn seventy this fall. I can tell you the exact week because the sycamores along County Road 7 go silver-green, and the last tomatoes on the vine taste like sun and pepper if you salt them before you bite. Life has a way of reminding you where you stand without checking a calendar. You look at your hands. You listen for the sound the refrigerator makes when it’s about to quit. You remember faces that are here and faces that are gone and you say thank you out loud, even when no one’s in the room.

I suppose you should also know this: I never finished high school. Neither did my husband.

There—said plain, like a nail driven flush. People either hear that and nod, the way neighbors do when you show them where the pipe froze last winter, or they purse their mouths like you put a shoe on the table. To me, it’s a fact. To some folks, it’s a verdict.

We had our reasons. My dad’s back went bad the summer I was fifteen, and the bank’s patience went worse. My mother ran the books for a little produce warehouse by the river, I started running invoices and wrapping pallets instead of writing essays on Gatsby, and the world did not end. It simply folded in on itself and handed me a broom and a pencil and said, “Here, make yourself useful.” I did. I learned what mattered: adding columns correctly, knowing which truckers were honest, which weren’t, and how to say no without making an enemy.

I met my husband—his name is Frank—one February morning when the pipes burst in Bay Three and the floor turned into a skating rink made of cabbage. He came in with a crew from a contractor we hired when things were bigger than a wrench. He was taller than me by a head and had that kind of quiet you don’t notice until there’s a problem and he’s already solved it. He handed me a length of hose, and I handed him a mop, and by evening we’d rerouted water through a bypass nobody had planned for and saved the crates stacked to the ceiling. If you want a first date story with white tablecloths and crowds clapping, I can’t help you. We fixed a leak. He bought me a coffee at 3 a.m. that tasted like burnt toast and survival. I married him nine months later.

He left school before I did—eighth grade—after his dad’s fishing boat went down in a storm off the coast with just the anchor left to tell you where. He went to work and never stopped. He could fix anything with moving parts, and he could convince anything with a ledger to balance. Later, when things got bigger than wrenches and ledgers, he built his own company, the kind of outfit that starts with three men in a rented garage with a leaky roof and ends up ten years later with an office full of good people and a sign on the door in three languages.

He likes to say he got his diplomas in overtime. I say I got mine in stubborn.

We raised our son, Tyler, on the principles I knew as sure as gravity: say what you mean, keep your word, eat at the table, hold the door, don’t laugh at people who cry, and never forget to call your mother on her birthday. We had one of those houses that lived in Saturday mornings—pancakes on the griddle, the radio playing old soul, homework spread across the table like a map. If you came through our front door, you were family. You left with leftovers and instructions, usually in that order.

Tyler was brighter than the rest of us. I don’t say that modestly, and I don’t say it with my hands in the air like I’m throwing confetti. It was simply true. He was the kid who’d take apart a toaster and put it back together with fewer screws and more sense. He read late with a flashlight and asked questions that made me check out more library books than I had time to read. When the counselor at the high school called him “promising,” I went out to the parking lot, sat in the car, and cried until the door fogged up. Not because promise was something we didn’t know. Because it was something he’d get to chase without a flooded loading dock dragging at his ankles.

He took that promise to college on scholarships and summer jobs and the kind of grit that looks like grace from a distance. He finished at a state university we’re still proud of, then went on to one of those Ivy League schools the magazines like to put on covers—graduate program, big seal, Latin on the diploma, robes that make a mother cry again because watching your child walk toward his life is a miracle in any language.

He met Aubrey there.

When he first brought her home, I thought, if you cut kindness into a dress and wrapped it in good person, you’d get this girl. She had manners and a voice like a song you can’t quite place, and she listened when Frank told the same story twice. She was smart, polished the way money and expensive libraries polish you, and she had a way of making Tyler look lighter on his feet. They laughed in the kitchen; he taught her how to flip pancakes. She wrote thank you notes that looked like calligraphy talking to itself.

Her family came from an entirely different world than ours—parents with hyphenated job titles and a townhouse with more art than wall—but from the start I told myself that life isn’t a team sport where people in different jerseys can’t share a table. Everybody brings something. You make it work. You say yes.

We said yes when Tyler said he wanted to marry her. We said yes when they asked us to meet her parents for dinner at a restaurant where the bread comes in a basket that looks like a sculpture. We said yes when the wedding planning started, when the emails arrived with swatches and venue options and spreadsheets that had more tabs than a legal brief. We said yes because love is a thing you bless if you can, even if the guest list is written in a dialect you don’t speak.

And then there was the afternoon the mask slipped.

We sat in our living room—Tyler by the window, sunlight across his jawline like he’d been carved by it, Aubrey perched on the edge of the couch as if proximity might smudge her skirt. Frank told them about the day Tyler got into state U on a full ride and we threw a party with so much potato salad the neighbors could have moved in and no one would’ve gone hungry. He said, “We always knew you were smart, son. You got it honest.”

Aubrey cocked her head. “Oh,” she said, that small Oh that sounds like a cough pretending to be a word. “You two didn’t go to college?”

“We didn’t even finish high school,” I said, because fakery has a smell, and I won’t wear it.

She blinked, a butterfly caught between flowers. Then her lips curled into something like a smile, only sharper. “Well,” she said, “that’s…surprising.”

“Life happens,” I said. “We had family to take care of.”

Frank squeezed my knee. Tyler reached for my hand and squeezed too. It’s funny, the choreography of small families in big rooms.

Aubrey leaned back and folded her arms. “Absolutely,” she said. “But I’m glad that intelligence wasn’t passed down like, you know…” She fluttered her fingers. “…a black hen laying a white egg.”

The room changed temperature. My face stayed polite because you can’t teach old dogs new tricks, but you can teach them when to show teeth and when to keep them politely in their mouths while you inventory the precise dimensions of the insult handed to you.

“That what they teach you to say at those Ivy League schools?” Frank asked, voice soft.

She smiled wider. “Was that too difficult a term for high school dropouts?”

I met her eyes. Tyler’s jaw tensed, then he let it go. You know the moment a child becomes a man when he chooses to carry the thing you’re too tired to. He didn’t that day. He let us carry it. I don’t love him less for it. Some loads you learn to lift by watching someone else.

We gave her leeway. We assumed she’d meant the joke to land differently, that nerves and family make poets sound like bullies and bullies sound like themselves. But in the months that followed, the pattern didn’t blur, it sharpened. At dinner, she’d glance at the pot roast and murmur, “Even someone with just a middle school education can cook, huh?” As if my hands had learned what they knew from anything but work. When she ran her fingers across the banister Frank built and said, “Nice house. Tyler must have helped a lot, right?” I learned what salt tastes like when you swallow it and call it soup.

When we told her—twice, ten times—that we paid our own way, that we’d paid Tyler’s tuition without asking and without bragging because that’s what parents do if they can, she shrugged and said, “That’s not what people are saying.” When I asked which people, she waved a hand and said, “My friends,” the way you swat at a fly that’s only high school educated and therefore not worth your time.

She took to leaving little notes after dinners, “Just a reminder: as part of Tyler’s new family, I won’t be responsible for caring for you when you get older.” We burned one in the sink on a Tuesday afternoon. Frank watched it curl and said, “We’ll be eating soup out of tin cans before we knock on her door.”

We tried to intervene gently. Tyler did it directly. He told her enough was enough, that she was confusing education with character, and I believed him. The wild thing about love is that it makes you think the person in front of you will morph into the best version of themselves if you tell them who they can be. Sometimes it works. Sometimes you get the version you already had, only more so.

When the wedding week arrived, I thought we’d weathered it. You can circle a storm if you know the roads. Then Aubrey knocked on our door with her hair in perfect curls and a clipboard that might as well have been a scepter.

“I have a favor,” she said, bright as a bell. “We’ve taken some money from you both for the wedding, so we’ll let you attend, but in return I want you to do something special.”

Frank looked at me. I looked at the ceiling and imagined the exact sound a chandelier would make if it fell in slow motion. “What is it?” I asked.

“A surprise speech,” she said. “For Tyler. Ten minutes. At the reception.”

“That’s a long time,” I said. “We’re not show people.”

“It’ll be adorable,” she said, as if we were children dressed up as the grandparents in a school play.

I inhaled. Said yes, because the body sometimes betrays you into civility.

“Oh,” she said, leaning in, voice lower like a dog whistle only the undereducated could hear, “and it needs to be in French.”

I laughed before I could stop myself. It wasn’t a nice sound. It had edges. “French,” I said. “That’s a strange choice.”

“A lot of my friends—and my family—speak it,” she said. “I don’t want people to look down on us because my in-laws are dropouts.”

She smiled like we were on the same team. “But hey, if that’s too hard, I understand.”

She left us with a parting “Promise you’ll practice,” and a wink that wasn’t a wink at all.

She thought she was building a trap. She didn’t know she was cutting a ribbon at the opening of our favorite old theatre.

Part 2

People think languages live only in classrooms with fluorescent lights and posters about conjugations. Some of them do. The French we learned lived in warehouses and airports, on loading docks and in hotel lobbies at 2 a.m. with a bad cup of coffee and a shipping manifest that suddenly wore accents grave and aigu.

Frank’s company got big enough to outgrow the county line, then the state line, then the line you draw in your head where a person who used to wrap pallets at fifteen thinks “International” is a magazine and not a business plan. We had clients in Montréal. We had partners in Lyon. We had a warehouse in Dakar for one brief wild year that taught me more about humility than any sermon. You can do business with interpreters. You can make friends in one language and buy forklift parts in another. But if you want to be welcomed, you learn to say please and thank you where you land. You learn to ask about a mother’s health without sounding like you’re in a book. You learn how to apologize in a way that makes everyone look down at their shoes and say, “It’s okay,” because you said it right.

We practiced at the kitchen table, not because we needed it, but because my heart said we did. Frank read aloud from a printout like it was a blueprint. I corrected his accent three times and then let his hands do the rest. He corrects me back by kissing my forehead when I get huffy. We argued over the relative charm of imparfait versus passé composé and then laughed because we were grandparents acting like teenagers playing the parts of people who never finished high school and still found a way to say “I built this life with you, stone by stone.”

The day of the wedding, we drove to the venue across town where the trees always think they’re in a movie. Big house on a hill, the kind of place my mother used to point to and say, “Those folks eat dessert on a Tuesday.” The grounds were manicured within an inch of their lives. Strings of lights hung from tents like someone had tried to catch fireflies and keep them polite. Aubrey’s friends—sleek in dresses that required contortions and probably help to zip—looked at us the way you look at something you’ve been told not to touch in a museum.

One of them “accidentally” bumped my shoulder in the corridor and didn’t say sorry. Another laughed into the rim of her champagne and said, “Oh my God,” in the tone reserved for shoes you wouldn’t wear if the world were ending.

“You okay?” Frank asked.

“I am,” I said. “But the thing about assumptions is they always make themselves visible from the back row.”

We took our seats. The ceremony was a wonder. Tyler cried when Aubrey came down the aisle, and I forgive everyone everything in those fifteen seconds. The officiant talked about vows like ropes instead of chains, and I wanted to clap at the metaphor alone. There were grandparents and flower girls and someone’s uncle with a camera who believed he was Spielberg. The music had a string section. I thought, we made it to a good place, even if somebody tried to ruin it with their mouth along the way.

The reception opened like a book: cocktails, introductions, a band that had clearly played this circuit since the Reagan administration and still knew how to make the old folks stand up. There was a Lively Announcer who liked his own voice more than any person should, and there were toasts that sounded like they’d been workshopped in a committee that couldn’t agree on line breaks.

“And now,” said the Announcer, voice tumbling across the room, “a surprise speech from the groom’s parents!”

We looked at each other. Tyler’s eyes widened. Aubrey’s mouth tilted in a way that would have been called a smirk in any other era. As we passed her table, she leaned in and murmured, “The French of old folks who dropped out of high school will be perfect for entertainment.”

I could have slapped her. I did not. I let the blood pass my ears and settle back where it belonged. I took the microphone. It was heavier than I’d expected. It fit my hand like a job.

I could feel the room brace for catastrophe. A few of Aubrey’s friends leaned forward, smiling in the way you smile when you want to remember everything you hear so you can repeat it later with edits. A few of Tyler’s college friends looked worried, like maybe we’d get lost in our own sentences and they’d have to clap extra hard to cover it.

“Bonsoir à tous,” I said. Good evening, everyone.

A silence fell so complete, you could hear the swish of satin. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Aubrey’s eyebrows jump like a startled cat.

I told them our names. I told them we were turning seventy this year. I said we dropped out of school when we were young because responsibility arrived and we answered the door. I said the French I was speaking had been learned in warehouses and boardrooms and over bowls of stew in a kitchen where deals were signed more often than not because we’d learned to listen to the person across the table. I said my husband now runs a company that started with one invoice book and now keeps a dozen families fed because work is a prayer said with your hands.

Frank took the microphone and, in a French so sturdy you could set a table on it, recited a little story about a customer in Lyon who’d once told him, “You have the hands of a man who builds bridges, not walls.” He said it with the cadence he learns numbers: steady, unembarrassed. Then, because he loves showing off in the least showy way, he said a sentence in Wolof and a sentence in Québécois, and the back half of the room whooped because they understood the joke and the front half clapped because the sound told them they should.

I took the microphone back. I told them how much we love our son. I told them the first time he rode a bike, he fell and laughed and got up because his father said, “Again,” and that’s what a family is. I said, in French—clear enough for the folks who learned it in dorm rooms, slow enough for the folks who learned it in kitchens—that a person’s worth has never lived on a diploma, that my husband and I had been on the receiving end of remarks about education that made us chew our food slower and choose our words like they cost money. I did not say Aubrey’s name. I did not have to.

I mentioned, because this is how you put your cards face up on the table and see who’s bluffing, that the request for a French speech had come the day before. I said we were delighted to oblige. I used the word oblige because it tastes like something you keep in a drawer for when you need it.

Someone near the back coughed in English, “Oh, damn.”

And then—maybe because I am not always a saint—I did a mean thing dressed like a kind thing: I thanked the bride for giving us the opportunity to speak in a language many of her guests could understand. I thanked her for “setting up this opportunity so that my husband and I, who only completed middle school, wouldn’t be looked down upon.” I did it with a smile. I did it with a tilt of my head that could be read three ways and one.

I closed with a blessing for the couple. I did it in English, because home is where your mother tongue lies down and takes off its shoes. The band struck up something lively. The Announcer tried to wrestle the room back into a script. The room refused.

I saw the expressions move across faces like weather. Aubrey’s friends stopped smiling. Tyler’s friends started to, the way you do when your hypothesis that your friend’s people are tougher than they look gets proven by data. Aubrey’s parents went pale and then paler. The couple at the next table leaned in and whispered behind their hands like maybe they too had entertained the idea that education is a scale and now someone had put a hand on the counter and redressed the measure.

Aubrey stood, hands clenched at the bouquet, and said in a voice that carried, “Thank you for that little…commotion,” and then she sat. Sometimes the most telling apology is the one you don’t make.

After the ceremony, there was a line of people and not enough time. Some shook our hands with the gratitude of people relieved to discover kindness isn’t the same as weakness. Some looked at their shoes. Some asked me where I learned my accent, and I said, “In places where not knowing it would have cost us work,” and they nodded like that answered questions they hadn’t known how to ask.

Aubrey’s parents rushed over, stiff with embarrassment and regret. “Mr. and Mrs. Harper,” her father said—the first time he’d said our name like it didn’t itch—“we’re so sorry.” Her mother took my hands in both of hers and squeezed so hard she left crescents in my skin. “We had no idea,” she said. “We’re mortified.”

“It’s all right,” I said. “Families are strange and human.”

They looked at Frank, then at each other, and her father blurted, “We have a business relationship with your company.” It came out like a confession and a prayer. “We value it.”

Frank smiled with just enough teeth. “We value all our partnerships,” he said. “Usually more when people aren’t calling us dropouts in our own house.”

I saw them both flinch.

Across the room, Tyler stood with his hands in his pockets, looking at Aubrey the way a man looks at the blueprint and realizes the wall won’t hold. She was crying. I felt the complicated ache of wanting to comfort a person you love who’s being hurt by someone you don’t, and also wanting her to sit in the hurt for a minute so she recognizes it next time before she causes it.

“Why is this happening to me?” she whispered to Tyler, just loud enough for me to hear because God likes a stage and I am sometimes necessary audience.

“Because you wouldn’t listen,” he said, not raising his voice. “Because you never listened.”

Part 3

Rumors are a kind of math that needs no chalkboard. They spread in the days after the wedding with the efficiency of dandelions and the utility of weather reports. People who’d smiled at Aubrey because she’d smiled first started to close their doors. The group chat I don’t belong to and have never seen had a violent allergic reaction to the phrase black hen lays a white egg when someone quoted it. Her closest friend dropped off a pie—pecan, store-bought and still good—in our kitchen with a note that said, “I’m sorry. We believed things we shouldn’t have.”

Tyler came by with a tool he didn’t need to borrow and sat at the table and didn’t ask for coffee for the first time since he was twelve. He held the mug anyway and stared at the steam. “I don’t recognize her,” he said finally. “Or maybe this is who she always was and I just loved a version I made in my head.”

Frank leaned back in the chair he built and made the sound men make when they know you want a map and all they have is a compass. “Love will make saints out of fools and fools out of saints if you let it,” he said. “What matters is who you decide to be next.”

“I asked her to stay with her parents for a while,” Tyler said. “She packed a bag with more shoes than anyone needs for a month and left like I’d insulted them. I didn’t. They’re fine. They just…don’t think I’m poor.”

He swallowed. “She wants to talk. I told her she needs to apologize to you first.”

Frank nodded. “Not for us,” he said. “For her.”

Over the next week, Aubrey called twice. The first time, she cried and told me she’d never meant to hurt me. I believed her about the not meaning. I did not mistake that for not doing. The second time, she came by with her hair pulled back and a sweater that didn’t try to be a conversation, and she stood on the porch and said, “Can we let bygones be bygones?”

“We never had bygones,” I said. “We had foregones. You kept telling me who you were, and I kept hoping you were wrong.”

She flinched. “I’m trying,” she said.

“Try where it counts,” I said. “Try at the dinner table with my son. Try at the doctor’s office with a stranger. Try at the grocery store with the checker who’s on hour nine.”

She opened her mouth, closed it, and left.

There are things you can forgive by the time you clean the coffee pot and hang the towel. There are things you forgive the year you learn you have high blood pressure and an acquaintance in church tells you to drink beet juice, and you do, and the world doesn’t end. There are things you don’t forgive, not because your heart is small, but because some fences are better than bridges if you want the grass to recover.

Aubrey kept trying. She sent elaborate apologies via text that read like legal documents, all clauses and no verbs. She offered to make dinner and bring a store-bought pie. She asked if we wanted to go to the museum with her on a Wednesday when we both had work and neither of us wanted to look at art that day anyway.

I ignored more than I answered. I am old enough to know when engaging is throwing a rope to a person who needs to learn to swim, and I have lived through storms enough to know the difference between weather and climate. I kept my climate steady. I invited my neighbor over to teach me how to knit a better scarf. I went to the library and picked up a book on nineteenth-century French poetry because spite will take you to the oddest places and then teach you something anyway.

Then Aubrey did the thing that made me soften, if not exactly forgive. She called and said, “Can I come over and listen to you talk about where you learned that French?”

It was raining. I had nothing to do that couldn’t be moved. I said yes.

She sat at the table she’d once called “rustic” like it might be a compliment if she said it with enough pretending and folded her hands. She looked like a child sent to the principal’s office in a movie. I made tea. I told her about the warehouse in Montréal where the floor manager taught me the phrase faire la file the same day he taught me where they keep the good croissants. I told her about the woman at the hotel desk in Lyon who corrected the way I said merci and then invited me to her cousin’s wedding, which I attended in a dress from a thrift store and cried at anyway. I told her about Dakar; I told her about the night Frank and I stood on a bridge in Paris with shoes that hurt and pretended the country we come from doesn’t have a crooked history with the country that one does. I told her that languages are keys and you shouldn’t be mad at people who carry them, even if they didn’t get them in the same place you did.

She didn’t cry. She listened. Then she said, “I was cruel.”

“You were careless,” I said. “Cruelty requires intent. You liked how smart sounded in your mouth, and you forgot to check whether it tasted like kindness.”

She nodded. “I don’t want to lose him,” she said.

“Then don’t practice losing him,” I said. “Practice keeping him.”

She left, and I watched her cross the lawn, and I wished good sense into her spine the way you wish sun into the first tulip bud of spring. Some prayers are better for the person who says them than for the person they’re supposed to fix.

Part 4

The video arrived in my inbox one morning from my niece, who owns a camera and a sense of timing and never asks permission to use either. The subject line read just: you need to see this. I clicked and waited for it to buffer in that slow way that makes you think the internet is tired too. The screen filled with the wedding hall, glittering and too white, the Lively Announcer with his chin high, the crowd turning to look. Then there we were: me in a blue dress that makes me look like the Delaware sky in October, Frank in a suit he owns because funerals insist on them, holding a microphone as if it were a wrench.

Aubrey’s face came into frame. The expression moved across it like weather: anticipation, confusion, surprise, a brief flare of anger, then something like humility that looked new enough to be uncomfortable. When I said merci, the women at her table closed their mouths. When I said oblige, one of them mouthed, “Oh, God.” When I said we were delighted to be asked to speak French, a man in a tux put his face in his hands and shook his shoulders to hide his laughter.

We laughed watching it in our kitchen. We laughed the way people laugh when the story ended the way it ought to for once and not the way it usually does. Frank pressed pause and put his arm around me and said, “You looked beautiful.” I said, “You sounded like a bridge,” and he kissed my cheek in that absent way of a man who has been kissing the same cheek since mops and burst pipes.

“You know,” I said, “school isn’t the only place to learn.”

“You want to take a class anyway?” he asked, not missing the joke under the question.

“Maybe I do,” I said. “Maybe I’ll finally figure out the subjunctive.”

He laughed, and we drove to the bookstore on Maple and let the smell of paper and coffee decide which aisle we took. I picked up a grammar book with a cover that looked too cheerful not to be lying. He picked up a manual on small engines because he cannot help himself. We came home with both and pretended we’d chosen something exotic when really we’d chosen the same things we’d always choose: language and movement, the talk and the doing.

Tyler and Aubrey circled each other for months after. They went to a counselor who had diplomas on the wall and a knitted throw over the arm of her chair. She didn’t use words like “reparenting” because that would’ve made my son run. She said things like, “Are you hearing each other?” and “Do you know what you sound like when you’re scared?” which is a question we should hang on the fridge.

Aubrey apologized again, this time to Tyler, not me. She did it in the car outside a grocery store, and he came over afterward and told me, “She used the word ‘pompous’ about herself,” and I said, “That’s a five-dollar word,” and he smiled, and we both knew it meant more because it cost her.

We didn’t undergo a magical transformation into friends. There are movies for that. We did something plainer: we got out of each other’s way. When she came over, she brought muffins and returned Tupperware clean. She stopped mentioning school. I stopped glaring when she wore shoes that made noise on our floors. We surrounded our love for the same person with the kind of truce that looks like manners and feels like weather—always present, sometimes stormy, often mild.

One Saturday afternoon in April, she came with Tyler for lunch and, after we ate, she stood by the sink with her hands on the towel and said, “I told my parents I don’t want them to use my degree as a mirror anymore.” I looked at her and saw the version of herself I’d wanted to bless, the one who understands that smart isn’t something you are, it’s something you do.

“Good,” I said. “It reflects better that way.”

She exhaled. “Violet,” she said, “you were right about one thing.”

“Only one?” I said, grinning.

She rolled her eyes. “About language. I started Spanish. I’m terrible. But I can order tacos without pointing, and the woman at the truck by the park laughed when I tried and then gave me extra cilantro.”

“Welcome to the club,” I said. “We have jackets. They say ‘Tried Anyway.’”

Part 5

Here is what I know now that I didn’t know when I was fifteen and learning to wrap pallets without splitting my fingers open: most of the things worth having aren’t on a syllabus. They’re in the space between a question and the person who answers it without making you feel small. They’re in the decision you make at a wedding when someone hands you a microphone and a trap disguised as a favor. They’re in the way you keep your voice level anyway, and you tell the truth in a language some people learned in school and some learned in warehouses and some won’t ever learn because they think the diploma did the job for them.

We still eat at the table. We still hold doors. We still say thank you out loud, even when no one’s in the room. Tyler and Aubrey are working on their life the way all people do who want one: by checking the bolts, oiling the parts, and learning to say “I’m sorry” in the languages it requires. They might have a baby this year. We might be insufferable about it. I will buy a book of lullabies in French and sing them wrong until the baby laughs. I will teach the baby the right way to eat a tomato. Frank will build a cradle so sturdy you could argue politics in it and it wouldn’t creak.

Sometimes I think about that phrase—black hen, white egg—and I wonder what makes a person say it and believe themselves witty. Then I remember the first time I watched a hen lay an egg: the ruckus, the surprise, the relief, the miracle of something warm in your palm handmade by a creature that knows nothing about your résumé. Life is unearned and also earned every day. The egg doesn’t care where you went to school. The omelet cares if you salt it at the right moment.

A few weeks ago, I went to the community center and signed up for a class. Not French—I’m doing fine. I signed up for algebra. I want to know what my son knew at fourteen that made numbers feel like friends, and I want to feel that click of a puzzle piece you didn’t know you’d been walking around with in your pocket.

The woman at the desk asked my birthday and typed it into a computer and said, “Wow,” like I’d just told her I was born in the year people discovered coffee. I laughed and told her, “I’m here to keep the rust off,” and she said, “Aren’t we all.”

Frank came with me to the bookstore afterward. We bought a used textbook with someone else’s notes in the margins and a mechanical pencil because it makes me feel like a student. We also bought a toolkit he didn’t need because he likes the way wrenches look on a pegboard, like soldiers at ease.

On the way home, we stopped for tacos at the truck by the park. The woman inside leaned down to the window and smiled. “Hola, Violet,” she said, because I keep trying, and people notice when you try. Aubrey would have liked the cilantro that day. So I ordered extra and brought it home in a foil packet and sent a picture to Tyler: your wife is going to regret moving out if she keeps missing this.

He sent back a photo of a pair of feet in socks on a couch—Aubrey’s, probably, or his—and a caption that said, “We’re figuring it out.” That’s all any of us are doing, high school diploma or not. Figuring it out. Learning to speak kindly. Learning to listen. Learning how to stand up at a wedding when it would be easier to sit down and say nothing.

I never finished high school. My husband didn’t either. Our French is good enough to make a room go quiet, our English is plain enough to set a table, and our love for our son is fluent in every language we’ve ever needed. If that’s not education, tell me what is.

We got home. Frank carried the tools inside. I put the algebra book on the table and smoothed the cover like I was making a bed. Ranger—our neighbor’s old hound who prefers our porch half the time because we don’t shoo him—thumped his tail and sighed like a happy man. I went out back and looked at the sky. The sycamores hadn’t turned yet, but they would. The refrigerator hummed the right note. The house smelled like cumin and soap. I said thank you out loud, even though no one was in the room.

And then I sharpened my pencil and opened to Chapter One.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her Part I —…

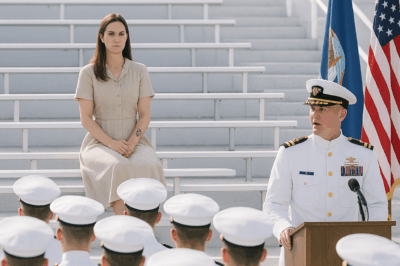

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze Part 1…

“What’s that patch even for ” then the colonel said,“Only five officers have earned that in 20 years

“What’s that patch even for” then the colonel said, “Only five officers have earned that in 20 years” Part…

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me

My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me. At dinner, my sister…

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence – That Was Their Biggest Mistake

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence — That Was Their Biggest Mistake Part I —…

End of content

No more pages to load