My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely…

Part One

It was supposed to be a quiet, perfect evening—the kind you memorize before it even happens because the hope inside you needs something to hold. I had spent the afternoon in our small Portland kitchen doing everything with intention: truffle mushroom risotto stirred low and slow until it sighed, asparagus tossed with lemon and garlic, a sourdough loaf I’d fed and shaped and baked from a starter I’d been tending for months. I lit candles. I set the table with the good plates—the ones we never used because we were saving them for “nice.” I smoothed wrinkles out of the linen napkins. I tucked a small gift box under my chair, white paper tied with a thin, gray ribbon. Inside: a tiny cotton onesie with watercolor foxes and firs.

I was six weeks pregnant. He didn’t know yet. No one did—no one but the woman who’d made it her life’s work to know everything before Dylan did: his mother, Joanne.

She had moved in nine months earlier “just until I get back on my feet,” she’d said, knocking on our door with a single, dramatic suitcase and a voice that trembled just enough to make Dylan soften. After her second divorce she needed family, she said; after a lifetime of being needed by him, he said yes. I wanted to be generous. I tried. I folded towels the way she insisted. I set the thermostat where she liked it. I invited her to walk with me even when the air between us felt like weather. But generosity has a taste. Hers tasted like vinegar.

When she breezed into the dining room that night in heels that clicked like punctuation, I knew better than to ask her to give us space. “Family dinners are important, dear,” she said, skimming my face with one of her fixed smiles. “Especially when you have secrets you think you’re hiding so well.”

It hit my stomach like the first bad wave—nausea had been finding me at every hour, not just morning. I breathed through it, the way the midwife blogs said to, and told myself not tonight. Not in front of the candles. Not near the gift box with the little forest.

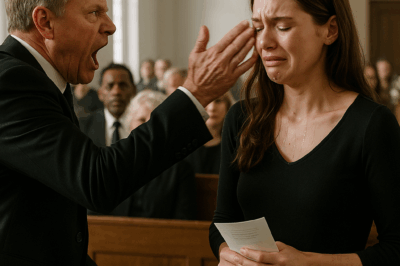

As I set the risotto down Dylan rose from his chair to help, but Joanne’s hand found his shoulder and anchored him. She leaned in. Whispered. I didn’t hear words—only watched his face change in real time, as if someone had slid cold glass over warm brown eyes. His jaw tightened. He looked at his mother, looked at me, and then he stood so fast the chair screeched across the floor.

“Is this true?” he demanded. “You’ve been lying to me?”

The spoon fell from my hand and hit ceramic with a small, doomed sound. “What are you talking about?”

“Don’t,” he snapped, stepping around the table. “Don’t play dumb, Maya. Did you think I wouldn’t find out?”

The slap came from nowhere and everywhere. A quick, practiced movement like a bad habit. Heat bloomed across my cheek before the pain did. Then the room tilted, and the wall was there, and I was on the floor. The taste in my mouth changed. My stomach clenched helplessly. My body chose me over dignity, and I threw up, the sourness climbing and spilling and ruining everything I had set to beautiful.

“Maya—Jesus—what the hell,” Dylan said, recoiling.

Something small slid out of my purse when it tipped, skittered across the hardwood, and bumped against his shoe. He bent to pick it up, and the world shifted again. He stared at the tiny window. Two lines. All the blood ran out of his face. He looked at the stick, at my stomach, at the hand he had used.

“Is this…?” His voice cracked.

“Yes,” I whispered, pressing one hand to my belly and the other to my burning cheek. “I’m pregnant.”

Silence expanded until it was almost a sound. The asparagus hissed in the oven. A candle guttered and caught again. Joanne’s mouth had flattened into a satisfaction so thin it could slice.

The door creaked open. “I heard shouting,” Tessa, our neighbor, said from the foyer. She stopped short when she saw me on the floor, the mess, the bruise already rising like something alive. Her gaze jumped from Dylan’s hand to my cheek to Joanne’s eyes. “Is everything okay in here?” she asked, but it wasn’t a question. It was an alarm.

Everything that followed blurred and sharpened, both. Tessa knelt beside me with a steadiness that anchored the room. “We’re going,” she said gently but not softly, gathering my bag, my coat, my keys. When she reached for my arm I flinched without meaning to; she slowed. “We’re going,” she repeated. Behind us, Dylan said something that wasn’t an apology and Joanne hissed something that sounded like, “She’s overreacting. You know how women get when they’re hormonal,” and then the door closed on all of it.

Tessa lived across the street in a second-floor walk-up that always smelled like cinnamon and clean laundry. She got me into the shower, turned the water too warm, found the biggest sweatshirt she owned and pulled it over my head like armor. I curled on her guest bed with the fairy lights glowing above it—the room she’d made for her niece when she visited—and held my stomach and tried not to shake the baby inside me with my shake.

The next morning she drove me to the clinic and held my hand while I listened for something I had never heard before. The ultrasound tech turned the screen, and there it was—a flicker, then a sound that felt like a rope thrown across a chasm: steady, insistent, ours. “Do you want me to record it?” the nurse asked, and I nodded because if I didn’t make this real outside my body, I’d wonder if I’d made it up.

That afternoon I sat on the edge of Tessa’s bed with her sweatshirt sleeves hanging past my hands and stared at my phone long enough to think better of everything. The recording glowed in a little gray bubble. I attached it to a message and typed two words: Your child’s heartbeat. Then I hit send.

His reply came in under a minute. Please. Can we talk. Just us. No Mom. Please, Maya.

Tomorrow, two p.m., I typed. Juniper & Brew. If she shows up, I walk away forever.

I won’t, he wrote back. I swear. I’m choosing you this time.

We met where we began. Juniper & Brew sits between Powell’s and the old movie house on 11th, a narrow place where the lighting flatters everyone and the windows fog in winter. He came in on time for the first time in months. He looked like someone who had fallen asleep in his clothes and then apologized to them. He paused as if he didn’t expect me to actually be there.

“Can I sit?” he asked.

I nodded and wrapped my hands around a mug I didn’t sip, as if warmth could be borrowed. He didn’t sit close. He kept both palms on the table, as if showing me he had left his weapons outside.

“I kicked her out,” he said. “Last night.”

My face didn’t move. We both watched the steam rise off my tea, as if it would draw shapes we could interpret. “She’s staying at a hotel,” he went on. “I packed her bags myself.”

I didn’t tell him I had heard Joanne lurking outside Tessa’s then, as if rage could keep a person standing. I didn’t ask him what lie she had told that turned his hand into a weapon. I watched his throat work when he said, “I’m so sorry,” and waited for the next part, because people who are sorry usually keep talking as if words can make time go backwards.

“I believed her,” he said. “That’s the worst part. I didn’t even ask you. She whispered ‘affair’ and ‘keeping secrets’ and I let it in because… because that’s easier than telling your mother you won’t be her little boy anymore. I’ve been hers since before I knew I had a choice. I thought I was protecting you when I got quiet. I wasn’t. I was protecting a pattern.”

There are moments when your body knows something before your brain decides. Mine sat taller without asking me. “You didn’t ‘let’ it in,” I said. “She taught you to live with it. You chose what you did with it.”

He flinched, but he didn’t look away. “I know,” he said. “And I’m not asking you to come home. I’m not asking you to forgive me. I will do whatever it takes for you to feel safe. I found a therapist. I booked couples counseling. I called an attorney.”

He slid two business cards across the table: a trauma-informed couples counselor, and a family law attorney. “She drafted papers,” he said. “If I ever touch you in anger again, you get full custody. No fight, no court. It’s notarized. I signed.”

Something cracked open in my chest that wasn’t fear this time; it was complicated and old and newer than the bruise on my cheek. “I have conditions,” I said.

He nodded before I named them.

“Your mother never sets foot in our house again,” I said. “Not for holidays. Not for five minutes. Not at the hospital. She gets no updates, no pictures. She becomes a stranger we used to know.”

“Done.”

“You go to therapy every week. We go together every other. You do the work. Not the sorry. The work.”

“I started yesterday.”

“If you ever raise a hand to me again, I press charges and file for full custody that day. There is no forgiveness waiting.”

He swallowed. “There shouldn’t be,” he said. “You deserve safety more than my redemption.” He lifted his eyes. “Our child does, too.”

“Then we agree on one more thing,” I said, my voice turning into something I had never heard from myself before. It sounded like a spine. “We don’t tell her story with your mother’s words.”

He nodded hard enough that I believed his neck might ache later. “I’m choosing you,” he said again, softer, almost to the table. “For the first time in my life.”

He waited for me to stand first. When I walked out, he didn’t reach for me. Outside the window the rain was mercifully, finally, not falling.

It took exactly three days for Joanne to test the boundary.

Tessa texted me from the front desk at the library: Silver Lexus has been idling outside for twenty minutes. She hasn’t gotten out. Just staring. Do you want me to call Dylan?

“Yes,” I wrote back. “And film from the window.”

Two officers arrived ten minutes later and did the thing men with badges learn to do: approach calmly, stay kind, keep the temperature low. I watched through the children’s section glass as they asked for her license and listened to her pivot into tears.

“I’m just worried about my son,” she said loudly enough for the librarians to hear. “His wife is unstable. She’s keeping me from my grandchild.”

When the officers asked her to leave, she tried a new angle. “Blood is thicker than restraining orders,” she snapped. “You can’t keep me from my family.”

“Ma’am,” one officer said. “You’re trespassing. If you return, you’ll be arrested.”

Tessa caught the whole scene on her phone without shaking. We took it to the attorney the next morning. By lunch we had a temporary restraining order. By dinner Dylan had emailed every relative with a statement he’d written himself: For our safety and our daughter’s, we will not be in contact with my mother. Any information you share with her about us will be considered a breach.

He took my hand that night and read the email out loud in our couples session with Dr. Patel, hands shaking after the last line. “My family begins with Maya and our child,” it ended, “and anyone who cannot honor that cannot be in our lives.”

Dr. Patel nodded once, not indulgently but like a mathematician acknowledging proof. “Breaking a generational pattern,” she said, “looks less like fireworks and more like this email. It is ordinary bravery repeated.”

We repeated it. When a package arrived at the library wrapped in beautiful paper with no return address—inside a silver rattle engraved with EMW and a note that said, Blood is forever—J—we didn’t bring it home and argue about intent. We photographed it, delivered it to the lawyer, and added the file to a folder labeled simply Safety. When a nurse on the labor-and-delivery ward pulled Dylan aside and said, “Someone has been calling asking for your wife’s room number,” we moved hospitals and registered under Tessa’s address. We made a password for daycare pickup before we picked the daycare. We told the neighbors. We told the barista at Juniper & Brew. We told the woman at the corner store whose kids played on our sidewalk that if a silver Lexus ever parked at our curb to call Tom, our cop friend, before she called me.

Dylan went to therapy every week. Every week he came home with a sentence scribbled on a sticky note he had to say out loud at our kitchen table. Sometimes it was, “Protecting my mother’s feelings is not my job.” Sometimes it was, “Grief can look like rage.” Once it was just, “I was wrong,” and he had to say it six times before it sounded like his voice.

He didn’t move back in. Not right away. We let the space teach us. He texted before he came over. He sat across the room and asked before he reached for my hand. He left groceries in the cooler on the porch when I said I didn’t have the energy for thank-yous. He painted the nursery while I slept on Tessa’s couch and sent a photo only after I said, “Okay.”

In our twenty-fourth week, the tech at the ultrasound asked if we wanted to know the sex. “It’s your call,” Dylan said, looking at me and not the screen. For the first time in a long time, his eyes had no flinch in them. “Okay,” I said. “Tell us.”

“It’s a girl,” the tech smiled.

I laughed so hard the gel jiggled. Dylan cried like something old had finally loosened. He touched my wrist and then my belly and said, “She will never confuse fear with love.” I believed him because I was watching him become the kind of man who understands those words are made of action.

Part Two

Labor arrived at 2:13 a.m. on a Tuesday, which felt right because Tuesdays are nothing special until your whole life fits inside one. It was a rolling pressure at first, then not. We followed the plan we had rehearsed more times than I had breathed that week: call Tessa, pack the last-minute things, check the back door, leave the porch light on so Tom would know which house to scan on his way to work. At the hospital, we gave the nurse the password instead of our names. “I love a plan,” she said, sliding our chart into the holder.

Twelve hours later, our daughter arrived with a cry that made me feel like someone had opened a window in a house I didn’t know was too small. She was all scrunch and damp and perfect. The nurse placed her on my chest, and everything I had been holding—grief and fear and shame and rage—ran out through my feet and into the floor and left me with only this: the weight of her, the heat, the dependence, the wonder.

“She looks like you,” Dylan breathed, and I laughed because she looked like herself more than either of us, but it felt kind that he wanted to find me in her.

An hour later, a bouquet of lilies arrived at the nurse’s station with no name and a card that read: To my first granddaughter. You’ll need your grandmother soon enough. Blood is forever. —J. The nurse brought it in holding the ribbon pinched like it might bite. “Do you want me to toss this?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “Bring it to security. Ask them to write her full name on the incident report.”

We slept in shifts. We released a statement to no one but ourselves: This child will grow up where the door is locked to what harms her and open to what heals. Tom dozed in a chair in the hallway with his badge tucked under his hoodie. Tessa snuck in a grilled cheese from the cafeteria and made me eat half even though I swore I wasn’t hungry. My mother sat in the rocker and hummed a hymn her grandmother taught her when she was a girl inside a different kind of hard.

We went home on the third day in a car that had never felt so deliberately slow. The house had changed under Dylan’s hands and after Dr. Patel’s sessions, but I didn’t feel the change until I opened the front door and realized my body wasn’t bracing. There were no lace figurines on the mantle now, no note on the fridge explaining how long to steep tea, no framed photo of a boy in braces labeled my little man always mine. There was my mother’s plant on the sill. There was the round table where no one sits at the head. There was sunlight in the nursery. There was a mural of tiny animals Dylan had painted in the weeks he filled with hard work instead of excuses.

We learned the choreography of new parents. We swaddled without expletives. We took turns at four a.m. We decided not to whisper in the nursery so she’d learn to sleep through laughter. We moved the couch two inches out from the wall to make room for the swing. We added a maker of particular coffee to the registry after night three. We used every pacifier in the container before deciding she’d be a thumb girl. We fought once about a diaper pail and then apologized without scoring points.

Joanne called from numbers we didn’t recognize. She left voicemails that started in tears and ended in threats. She wrote a letter in looping script about rights and forgiveness. We didn’t respond. We kept a folder. On a bright afternoon, Dylan saw her in the produce section at the market where we buy apples. She made a beeline for him with a look in her eye that used to work. He turned on his heel and found the manager before she reached him. “I have a restraining order against that woman,” he said calmly. “If you need paperwork, I can bring it to you.”

When he told me later, he looked more tired than triumphant. “I felt sad,” he admitted, “for about six seconds. Then I thought about how normal felt like this when I was a kid—everyone tiptoeing around one person’s feelings—and I realized I was sad about that, not about her.”

I kissed our daughter’s forehead and then his. “You keep choosing us,” I said.

He nodded. “I keep choosing me, and that leads me to you.”

At two months, Elena laughed for the first time. Not a gurgle. Not a reflex. A full-body giggle that startled her into more of them. My mother burst into tears. “I forgot how sound can change the temperature,” she said, and sat down on the floor so she’d be closer to it.

We took a walk up Alberta Street on a morning that pretended to be spring. A woman with a toddler on a balance bike stopped to peer into the stroller. “Oh, she’s a little poem,” she said, and I thought how women hold up half the planet by telling the truth like that to each other.

At three months, we brought Elena to Dr. Patel’s office and sat her on the couch between us while we talked about sleep and triggers and how forgiveness is not a door you walk through once but a field you cross over and over with different weather each time. Elena gurgled and grabbed her own feet, and Dr. Patel, who does not coo, cooed.

At four months, I went back to work part-time at the library, the place that taught me how to order chaos with labels. The youth wing smelled like crayons and hope. The story time rug was still stained in the shape of a giraffe. I slipped back behind the desk and felt something settle in my bones—the part of me that is a librarian because books taught me to live in more than one world at a time.

At five months, the silver Lexus reappeared at the end of the block and then left when Tom walked casually down the sidewalk with a leash he did not need because the dog had died two years before. “Old habits,” he said later, sipping coffee on our porch. “She’ll figure out there’s nothing left to steal.”

At six months, we baptized Elena on a Sunday when the light came through the church windows like mercy. We stood at the font with water and promises and the baby made a face like she wasn’t sure about all this but would allow it. Our friends surrounded us and said the words back the way they’re designed to be said: we will help. My mother held a napkin and dabbed at her eyes and at the ends of Elena’s hair. Tessa and Tom stood like bookends. Dr. Patel came and sat in the back for a while and left a card later that said, Cycles break here.

We didn’t invite Joanne. We didn’t tell her. We told the truth about her when we had to in sentences that did not add adjectives.

Grief is not a straight line. We found that out one night when sleep didn’t come and the baby didn’t either and Dylan stood at the sink scrubbing a bottle like it had insulted him. “I see her sometimes,” he said to the faucet. “In the corner of a store. Behind me in the mirror. In how I freeze when the phone rings. I hate that she still lives rent-free in my nervous system.”

I leaned against the counter and watched him not look at me. “What do you do then?” I asked.

He rinsed and set the bottle on the rack. “I listen for this,” he said, and tipped his head toward the nursery where our daughter was snoring like a tiny bear. “And for your laugh when you read her that ridiculous book about the sneezy cow. And for my own voice when I say no.” He wiped his hands. “When I hear the present, she gets quieter.”

We made a list on a sticky note and put it on the fridge under the magnet shaped like Oregon:

Sleep is hard for saints and sinners.

Therapy is oxygen.

The kitchen table is more important than the dining room.

Boundaries are love in practical clothing.

We are not our parents’ worst choices.

We can be our child’s best chance.

We read it out loud when we forgot.

It would be neater to end here, to sew up the story with a tidy hem and say we lived happily after in a house that smelled of bread and baby shampoo. But the truth is better than neat. It is a living thing. It grows and scabs and startles and warms.

A year after Elena was born, we threw a small party in the backyard. A string of lights. A banner I wrote with a library marker. My mother made cupcakes with too many sprinkles. Tessa brought a potato salad people will talk about for the rest of their lives. Tom grilled corn. The neighbor kid who mows our lawn for free if we let him hold the baby came and held the baby. We opened gifts no one needed and loved them anyway—a board book with teeth marks by the end of the night, a sun hat she would rip off every time, a tiny sweater my mother started the day the cardiologist said the word surgery and finished the day Ben called with the donation.

There are pictures from that afternoon; they live in frames and on a fridge that currently has three fingerprints and a smear of mashed banana. In one, Dylan is laughing with his head thrown back in a way my therapist says means joy returned to the body. In another, my mother is holding Elena to her chest and whispering something I can tell by the look in her eyes is a prayer. In a third, I am caught mid-laugh with a cupcake in my hand and frosting on my ring finger. When I look at that one, I think about candles I lit and blew out alone.

After everyone left and we were stacking paper plates like poker chips, the silver Lexus rolled slowly past our house and kept going. I saw it. Dylan saw it. We didn’t speak. We didn’t freeze. I shut the gate. He locked the deadbolt. The baby giggled in the high chair at nothing and everything, and the world stayed the same because we had learned how to make it so.

Later, when the house was quiet and the lights were off and the baby’s breath was the metronome by which we measured our own, Dylan whispered, “Do you ever wish we could go back to before?”

“No,” I said into the dark, surprised by how certain it sounded. “Because who we became after is better.”

He reached for my hand under the sheet and found it. I thought of the risotto, the slap, the stick that slid across the floor, the neighbor with a stern jaw and soft hands, the ultrasound heartbeat, the email to a family that had to be taught where families start. I thought of Dr. Patel’s patient nod. I thought of a silver rattle and a restraining order and a nursery wall where a painted fox looked like it might wink.

I thought of our daughter’s laugh.

Cycles break. Not with noise, but with choices. We chose again and again until it felt like a habit. We will choose tomorrow when she throws peas at the dog and in ten years when she slams her door and says she hates us and in twenty when she walks into a world that will try to tell her what love looks like.

We will tell her what it truly is.

It is this: a kitchen table with no head. A father who learned to say no to the person who named him. A mother who understood that silence protects no one. A neighbor on a Tuesday. A therapist’s card. A plan taped to the fridge. A laugh in the dark.

We didn’t just survive her. We built a home she can never enter. We didn’t just bring a baby into the world. We changed the world we brought her into.

And that made every scar worth it.

END!

News

Airport Security Dog Wouldn’t Stop Barking at a Pregnant Woman — Then Everyone Learned the Heartwarming Truth. ch2

The winter morning at Brighton International Airport had been humming along in its usual way — rolling suitcases clicking over the tile,…

“My Mommy Won’t Wake Up…” — The Cry at the Airport That Sent a K9 Officer Racing Against Time. CH2

The airport was unusually quiet that Sunday morning. Officer Janet Miller adjusted her duty belt as she and her K9…

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”— So I Chose Revenge. CH2

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me and Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”—So I Chose Revenge Part…

My Brother Kicked Me Out After My Divorce, So I Prepared an Unexpected Surprise. ch2

Part 1: An Unexpected Betrayal I stood in my brother’s marble-floored foyer surrounded by moving boxes and the remnants of…

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

Jeanine Pirro and Tyrus Declare War on CBS, NBC, and ABC—With $2 Billion Backing, Fox News Makes Its Move. ch2

In a shocking move, Jeanine Pirro has declared war on CBS, NBC, and ABC, and she’s not doing it alone….

End of content

No more pages to load