My Husband Cheated with My Best Friend and Said “She’s Pregnant, Evelyn”

Part One

“I’ve been sleeping with your best friend.”

The words do not land—at first. They hover, weightless, like dust motes in the afternoon light of our living room. Then they thicken, gather, and fall. They fall through my throat and into my chest and split something I cannot name.

I stare at Asher. Spine against the bookshelf. Hands flat to the oak. The room goes full of sound—the clock, the refrigerator, the distant siren two blocks away—and somehow I only hear his breathing and my own. Too fast. Too shallow. I can’t tell whose.

“How long?” I ask. I have to speak slowly to keep my voice from veering off the road. “How long have you been lying to me, Asher?”

“A year,” he says, looking away like the punchline might be written on the wall behind me. “It started as friendship. It… grew.”

My mouth opens. No words arrive. A year is four seasons and thirteen rent checks and twelve birthday texts to her and an anniversary dinner where he toasted to “my forever.” A year is two hundred and sixty commutes shared and the way Natalie knelt on the floor with me to build the bookshelf I’m leaning against right now.

“You don’t get to say ‘grew,’” I manage. “Plants grow. Children grow. Cheating doesn’t grow—it hides.”

He presses fingers to the bridge of his nose and exhales. “I want a divorce, Evelyn. I’m done pretending. I can’t live a lie anymore.”

I laugh—sharp enough to slice. “You’ve been thriving in a lie.”

“We had a life too small for us,” he fires back, anger quickening his tone. “You’ve been married to your work. You don’t hear me. Natalie… she sees me.”

There it is: the soft-spoken cruelty of a man who needs a reason worse than he needs the truth.

“And?” I ask, because I want him to say it all. “What else.”

His jaw shifts. He meets my eyes and doesn’t blink. “She’s pregnant, Evelyn.”

It is a sentence with its own weather system. The room tilts; the floor moves; a wave rushes up from the baseboards and breaks over my head. Pregnant. Natalie. My best friend with a hand on her paintbrush and laughter that used to fill this room. I picture her palm on a belly that hasn’t yet risen and something in me tries to crawl out of my own skin.

“You got her pregnant while you were married to me,” I say. My voice feels like someone else’s—calm, classroom. “While she was sitting on my couch eating my tiramisu and telling me I work too hard.”

“We’re going to be a family,” he says. “The family I wanted. The one you—” he gestures vaguely, as if he can smear the rest of the sentence away.

“—didn’t schedule to your liking?” I offer.

“—weren’t ready for,” he says, softer. “I was.”

“You were ready to be a father,” I say, “but not to be honest.”

His mouth hardens. “You’ve made your choice every day for years, Evelyn.”

“So have you,” I say, and I watch him reach for the doorknob like he’s reaching for a life raft. “Every day for a year you chose her.”

He pauses, hand on the cool brass. “Do what you need to do. It won’t change my choice.”

The soft click of the door is the kind of sound you don’t realize can be violent. I don’t remember deciding to sit. I am on the floor with my back to the sofa and the quiet begins to ring. I look at the framed photos on the mantle—Asher with his arm around me on a bluff above the river, Natalie with paint on her cheek the day she moved into her first studio, the three of us on New Year’s, champagne flutes in a triangle between us. The glass gleams. I wonder briefly whether glass can feel ashamed.

When the tears finally come, they arrive with a vow: I will not drown in this. I will not let a year of his lies rewrite the story I’ve been telling myself about who I am. If there’s truth under this rot, I will find it. If there is a price to be paid, I will calculate it and send the invoice.

Two days later, I sit across from a private investigator who looks like every private investigator in every movie ever shot—suit too old to be stylish, eyes too sharp to miss anything, voice like gravel rolled in honey.

“This is what I’ve got so far,” he says, sliding a manila envelope across the table as if it might blow away. “Paper trail, photos, dates, names. He’s generous.”

I open the flap. Inside: bank statements, transfers, a lease for a loft with a signature that isn’t Asher’s but is paid for by him, receipts for art supplies it would have taken Natalie a year of commissions to afford. A photo of my husband’s hand—familiar vein, familiar scar—on the small of my best friend’s back.

“How long,” I ask, though I already know.

“Six months of money,” he says. “Photo evidence beyond that. I can keep digging.”

“You’ll keep digging,” I say, and my voice holds.

On the sidewalk outside, the city noise is a mercy. Sirens, someone arguing into a phone, the hiss of a bus’s brakes—all of it human, none of it personal. I cannot go home. Home lives under a bell jar now and every time I breathe near it, the glass fogs. I walk until the streets around me remember my name, and without deciding to, I wind up at Natalie’s studio.

She looks up when I enter, and for a fraction of a second, the rush of relief in her face is unguarded. “Evelyn,” she says, and then the recognition of the moment chases the relief away. “What are you—”

“Here?” I say, holding up the envelope like a passport. “Research. Fieldwork. Pick your noun.”

Her paintings—once explosions of color and place—are dark now, the palette turned low, edges smudged. The room smells like turpentine and fear.

“I know about the money,” I say. “The rent, the supplies. I know who signed for your loft. I know he told you exactly what you needed to hear.” I watch her fumble for a script. I don’t let her find one. “How long have you been letting him lie to us, Natalie?”

She presses her palms together like prayer might be hiding in there. “He said he was leaving you,” she whispers. “He said you didn’t want the things he wanted. He said he loved me.”

“Did he say he respected me?” I ask, and the question hangs there like a chandelier we both know is about to fall.

Tears rise. They gather. They spill. “I didn’t mean to hurt you,” she chokes out. “I never meant for any of this. He made me feel—”

“—like the first girl who ever saw him,” I finish for her. “He’s very good at that.”

Her hand drifts unconsciously to her stomach. I hate that my body notices, that some old reflex flickers and has to be held in check.

“He said he wanted this baby,” she says, and it sounds like a plea to the god of revision.

“Asher wants what’s on the other side of the locked door,” I say. “When he gets there, he wants the next one.”

She crumples onto the low stool she uses when she’s painting fine detail. She sobs the kind of sob that empties a room. It does not move me the way it would have six months ago. I am not made of stone. I’m just… mined.

“I hope the thrill was worth it,” I say. My voice is quiet because shouting would be a mercy I’m not feeling. “Because the invoice just arrived.”

I leave her in a room full of her own choices.

Liam Hastings’s office lives high over the city in a building that takes itself very seriously. He meets me in a navy suit that fits like a promise and a handshake that says I’m not here to be liked.

“Evelyn,” he says, and his voice is a key in the lock of my own determination. “I’ve reviewed the preliminary. You did your homework.”

“I hired excellent help,” I say, and slide the PI’s envelope across the desk. “And there’s more. Joint accounts bleeding. Transfers to a personal account not in my name. Not in his, either.”

He reads in silence in a way that makes me feel both seen and spared. When he looks up, there’s a glint in his eye I recognize from courtrooms and stories whispered at firm holiday parties. It is the beginning of a plan.

“Infidelity is one thing,” he says. “Financial misconduct is quite another. We can work with infidelity in divorce court; we can eat with financial misconduct.”

“Eat?” I echo.

“Eat,” he confirms. “His share. His reputation. His future options. You asked for hardball. I don’t even own a softball.”

A laugh escapes me, startled and genuine. It occurs to me I haven’t heard one of those in days. He smiles, not for long, and the work begins. We talk strategy and statutes, jurisdiction and leverage. He asks the right questions and tells me the truth when it isn’t pretty. He doesn’t once suggest that forgiveness is a kind of currency I’m obligated to spend.

At some point, coffee arrives. It tastes like a decision made at midnight. When I stand to leave, the skyline is bruised with evening.

“You’re not alone in this,” Liam says, and it’s the kind of line that could sound like a script in another mouth. It doesn’t in his. “He underestimated you.”

“He always has,” I say. “That’s about to become a very expensive habit.”

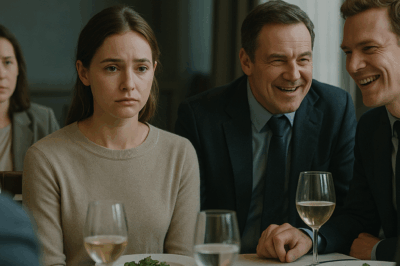

I ask Asher to meet me in a public place because I do not trust my hands if he’s close enough to touch. A café two blocks from our apartment: neutral ground with witnesses and too much light. He arrives with his chin lifted like he’s already survived the worst of it.

“We’re done, Evelyn,” he says, before I can sit. “I don’t know what you think you’re going to accomplish with theatrics. I’m starting over with—”

“—with Natalie? Yes,” I say softly. “You mentioned. I brought you something.”

I spread the papers out on the table between us like tarot. Bank statements. Lease agreements. Photos. A side-by-side of his signature and the one on the “anonymous” wire transfers. He touches nothing. He doesn’t have to. The color has already left his face.

“This is nonsense,” he says, voice too loud. “You can’t prove—”

“I can,” I say, and every syllable clicks into the next. “And I will. And I would have fought for us even now if you’d ever respected us. But you chose demolition over renovation.”

“What do you want?” he demands. “Money? The house? You always wanted everything.”

“I want nothing that belongs to you,” I say. “I want what belongs to me. I want my mother’s ring, my grandmother’s piano, the half of the equity you don’t get to pretend is yours because you found someone who laughs at your jokes. And I want you to learn the anatomy of consequence.”

His smile turns mean. “You really are a litigator at heart,” he says. “Vindictive suits you.”

“Justice suits me,” I reply. “And it’s in season.”

“Careful,” he says, leaning in. “You’re not the only one with secrets.”

“Then bring them,” I say, and I stand. “Bring everything you’ve got. And meet everything I’ve got.”

His hand twitches like he’s about to reach for me and then doesn’t. I leave him with his coffee and the papers and a bill he never expected to pay.

Two nights later, my phone rings at 1 a.m. The name on the screen could still stop my heart in another life. In this one, it just rearranges my furniture.

“What,” I say, because please is expensive these days.

“Evelyn.” Natalie’s voice is cracked and raw. “I need help.”

The silence after those three words presses against my ear. I can hear her breathing and something in the background I cannot place.

“Try another number,” I say. “Try the one that paid your rent.”

“He won’t answer,” she says. “He… he told me to get rid of it. The baby. He said he never wanted—” She swallows. “It isn’t his.”

The room does the tilt thing again. Slower this time. Not because the news hurts. Because it fits so neatly into the shape of a man I should have believed sooner.

“Of course it isn’t,” I say. “Of course.”

“I thought—” She is crying in that hiccuping way that makes every sentence two sentences. “I thought I could be… I don’t know. But Evelyn, please. I have information. Paperwork. Messages. Things he did at the hospital you don’t know about. If you help me, I’ll help you.”

“You’ll help yourself,” I say. “And I’ll use it.”

“Fair,” she whispers.

“Send me what you have,” I say. “Now.”

I text Liam: Natalie just called. Baby isn’t his. She says she has dirt.

He replies in under a minute: We like dirt. Tell her to upload to this secure link. I’ll vet it before dawn. You sleep.

“Sleep,” I text back, and we both know I won’t.

The files start arriving at 1:21. I watch the names populate a folder like little indictments: pediatric_dose_override.png, charity_board_emails.pdf, transfer_protocols.docx, as_callahan_voicemail.m4a. A recorded call where Asher tells Natalie which accounts to use and when, how to keep the amounts under the threshold that pings a human. Screenshots of messages in which he mocks the idea that vows mean anything past dessert. A spreadsheet of “consulting” fees he received from a supplier he’s supposed to monitor for safety.

I forward it all to Liam and stare at the ceiling until morning.

When he calls at 7, his voice carries the kinetic calm of a man who runs toward a fire with water in both hands. “It’s worse than we thought,” he says. “And better.”

“Better?”

“Because now it’s not just divorce court,” he says. “It’s the board.”

“What board,” I ask, even though I know. Even though I chose not to think about the other people he could hurt. “Liam—”

“We’re not going after him for sleeping with someone,” he says. “We’re going after him for practicing medicine like rules are for other people. You were never small, Evelyn. You just married a man who makes everything he touches small.”

I sit up. I breathe. I say, “Okay.”

“Good,” he says. “Put on something you like. We have a hearing to prepare for.”

The first half of war is gathering your weapons. The second half is deciding you have the right to use them.

By noon, we’ve filed a formal complaint, delivered the packet to the hospital ethics committee, and booked a date with the state medical board. We go line by line through the complaint like it’s an exam you can only take once. Liam smooths my testimony where my anger frays it and leaves my anger where it is an arrow. Natalie agrees—astonishingly—to sign a sworn statement. She arrives to do so in a sweatshirt two sizes too big and a face two years older than last month. She won’t meet my eyes until the third page. When she does, I let her look.

“I’m sorry,” she says.

“I’m sorry too,” I answer. “For all of it. Don’t mistake that for amnesty.”

“I don’t,” she says. “But I have a baby. I have to be someone new.”

“Then be,” I say. “Start now.”

That night, I dream that the living room clock grows a mouth and tells me the time is up.

The week before the hearing, Asher tries to bargain. He shows up outside my building like the past twelve months can be erased in an afternoon.

“You don’t have to do this,” he says.

“You do,” I answer.

“Think about your reputation,” he says.

“I am,” I say.

“You’re not a vengeful person,” he says.

“Not by nature,” I agree. “By necessity.”

He goes quiet then, because this is the part where the person who got forgiven every time learns there is a ledger after all.

“You were going to be a father,” I say, feeling the old ache flare and then pass. “You were going to be a husband. And you were neither.”

“You’re enjoying this,” he says, as if my joy has anything to do with his consequences.

“No,” I say, and it is the plainest truth I’ve spoken all month. “But I am going to finish it.”

He looks at me then as if I’m the stranger. He’s not wrong. I barely recognize my own posture—chin lifted, shoulders square, knees unlocked like a fighter who understands her own weight.

When he leaves, I let the door to my building close slowly enough for his reflection to disappear.

On the morning of the hearing, the air smells like rain trying to remember how. The boardroom is colder than it needs to be; every boardroom is. A long table, wood polished enough to reflect mistakes. Men and women in suits who learned how to keep their faces still while other people break.

“Dr. Callahan,” the chair says. “The allegations are… extensive. You have the right to respond.”

Asher stands. For a second, I think he will apologize. Then he opens his mouth and tries to explain. He tries to make risk sound like innovation and fraud sound like the price of speed. He tries to shape himself into a man who got stuck in the gears of a machine he was just trying to make run better.

The chair listens, pen motionless. Then the pen moves.

“We have standards for reasons that have nothing to do with your convenience,” she says evenly. “You are not the exception. You are the problem we exist to solve.”

Liam’s questions are clean. They land and stay landed. Natalie’s testimony is quieter than I expected and more devastating. Compassion lives beside accountability on her tongue. I don’t speak long. I don’t need to. I say the word “vows” once, not as a weapon, but as a measure.

The board recesses. They deliberate for less time than it takes to bake a loaf of bread. When they return, the chair’s voice carries the kind of finality that leaves no bruise because it leaves no doubt.

“License revoked,” she says. “Effective immediately. You are barred from practice in this state and will be entered into the national registry of disciplined physicians. If you appeal, you’d better bring a better story than this one.”

Asher sits back down in a chair that looks suddenly too big for him. For a moment, his face creases into something like a person I used to know. Then it is gone.

Outside, the sky decides rain after all. Liam takes my hand on the courthouse steps the way a man takes a hand when the person attached to it is the point, not the prize.

“You did it,” he says.

“We did it,” I say. “And I didn’t do it to him. I did it for me.”

He nods once, like that’s the only answer that matters.

When we turn to go, Natalie is there with a stroller too new to belong to her. She’s carrying her baby. The tiny face scrunches the way all new faces scrunch. The feeling that moves through me is not the one I was afraid of.

“Thank you,” she says. “For… not letting me lie to myself anymore.”

“We all deserve a second chance,” I say. “Some of us had to run through fire to get to ours.”

She smiles like a bruise healing. “We’ll get there.”

“We will,” I say. “In different directions.”

When I get home, the living room clock says the same time it always does. I don’t believe it anymore. There is no right time to stop making yourself small. There is only the moment you do.

Part Two

Divorce is not a single event; it’s a series of small endings punctuated by paperwork. That first week after the hearing, my lawyer’s office becomes the backstage of the life I am preparing to walk onto. We take inventory—assets, debts, items imbued with meaning only because I touched them every Tuesday for a decade. We make lists and cross things out. We keep the ring that belonged to my grandmother. We donate the dinnerware we bought because his mother said it made a table look “respectable.” We sell the apartment because its bones know too much and I deserve ceilings that don’t whisper.

Liam drafts the settlement the way you draft a will: precisely, without apology.

“He’ll fight the numbers,” he says. “And then he’ll settle. He can’t afford the discovery if we go full forensic.”

“What about the publicity,” I ask, not because I care anymore, but because I should pretend to.

“Publicity follows noise,” he says. “We made our noise in the right room. The rest is just paper.”

I walk the city in a way I haven’t since I was twenty-three and still believed that you could run fast enough to reinvent yourself. Turns out, you can. You just have to run through, not away.

The day the settlement signs, the sky is the color of forgiveness. Asher’s lawyer emails at 4:03 p.m.: Fully executed. Keys transferred Friday by noon. I stare at the line like it might be a trap. It isn’t. It’s just an ending wearing a blazer.

I don’t cry when I hand over the keys. I thought I would. Instead, I put them on the counter exactly where we used to drop them after a night out and ask Liam if this is what relief feels like when it’s too tired to raise its voice.

“Something like that,” he says.

We get coffee at the place on the corner that started putting my order in when I walked in three months ago and stopped asking where Asher was when I stopped flinching at the question.

“So what now,” I ask, because even the strongest narrative has to decide what to do in the next chapter.

“Whatever you want,” he says. “I know a realtor who finds impossible apartments for people who insist on hardwood and southern light.”

“I want a small kitchen where I can hear myself think,” I say. “And a window that lets me see something growing.”

“I know a place,” he says.

I move into a second-floor walk-up with a stubborn old maple outside the bedroom window and a neighbor who waters the geraniums on his fire escape while playing Coltrane too loudly and a landlord who has opinions about paint colors and is wrong. The first morning I wake there, I brew coffee in a pot I choose for its shape instead of its story. I drink it out of a mug that says Nevertheless because of course it does. I put the divorce decree in a folder labeled archive and the medical board decision in one labeled record and tuck both into a box in the back of the closet where I also keep the sweater my mother knitted me when I passed the bar. I keep the red lipstick I used the day of the hearing on the dresser because talismans come in many forms.

Natalie texts occasionally. Photos of the baby asleep with one fist under her cheek. Notes about a class she enrolled in to finish the degree she abandoned when her life felt like a painting someone else kept “fixing.” None of the texts mention Asher. I am not sure whether that’s humility or strategy. I don’t ask. She has a therapist. So do I. We overlapped twice at the reception desk and pretended not to notice.

One afternoon, six months to the day after the hearing, a letter arrives from the hospital. Not to me, but addressed to me anyway, if you read the white space.

Dear Ms. Reyes, it says, and I stop for a second because I have not heard my unmarried name out loud in a while. Thank you for your advocacy. We have implemented the following reforms… and the list is long enough to make me sit down. It includes words like audit and consent and whistleblower and anonymous. It includes a line about a new ethics training module that uses redacted versions of our case. It includes an apology not for what was done to me—institutions rarely apologize to individuals—but for what was permitted on their watch. It is not enough, because nothing ever is. It is a start, which is what everything is.

I send a photo of the letter to Liam with the caption: We planted something.

He texts back a seedling emoji and then, because he is a lawyer and not a poet, Also, the judge granted your restraining order extension. He’s barred from contacting you for another year.

That night, I take a bath in a tub that is not big enough to submerge regret but is big enough to make my shoulders forget how to carry it. After, I sit on the floor with a folder of papers I have been avoiding because I hate new beginnings dressed as business. They are the incorporation documents for the non-profit I started drafting on a napkin the week after the hearing—a clinic for legal triage for women (and men, sometimes) who need a short, sharp map through the first thirty days after betrayal. We are not therapists. We are cartographers. We tell you where the quicksand is and where the good bridges are and which lawyers won’t mistake your fury for your case.

I name it First Light because every cliché is true at least once.

The day we file, Liam buys a bottle of Champagne and my mother brings empanadas from the place in Queens that has been saving our lives since 1998.

“To making maps,” my mother says.

“To burning bad ones,” I add.

“To knowing the difference,” Liam finishes.

We sit on the floor and eat and laugh and argue about whether First Light should have a tagline. We decide it shouldn’t. The people who need it will know what it is when they see it.

Three months later, I run into Asher on a street too narrow for comfort. He is thinner. He has shaved his beard. He looks like a man auditioning for his life. He does not speak. I nod once, not unkindly, and keep walking. The air behind me stays still.

The next day, a thick envelope arrives from his attorney. It is not a suit. It is not an apology. It is a check for the last installment of the settlement. It is large enough to buy four months of sleep.

I call Liam to tell him and then, on impulse, I call Natalie. She answers on the third ring, her voice full of Cheerios and nap schedules.

“I’m glad you called,” she says. “I was going to text. The class I’m taking—we had to write about a moment we’d undo if we could. I wrote about the day I told you I was in love with him.”

“You never told me,” I say.

She is quiet. “I did. In a thousand ways. I just never used those words. I’m sorry I made you translate my cowardice.”

It’s the kind of sentence that lands and stays landed. It helps. It does not cure.

“We’re building something,” I say. “First Light. If you ever want to paint the walls in the lobby…”

She laughs, startled. “I’d like that.”

“Bring the baby,” I say. “We have good light.”

“Good,” she says. “She deserves it.”

“So do you,” I say. “So do we.”

The morning of First Light’s opening, the mayor’s office sends a representative who says words into a microphone about resilience and community. I imagine rolling my eyes at twenty-five and realize I’m not twenty-five. Resilience is real, community is oxygen, and microphones are fine if you use them to say something new. When the speeches end, I move through the lobby greeting people who look like I looked six, nine, twelve months ago. They hold folders. They hold phones. They hold themselves together with string.

A woman stands a little apart from the crowd, staring at the pamphlets like they might be in a language she used to know. Her fingers tremble. She catches me watching her and does not look away.

“First time,” she says.

“First light,” I answer, and it is not scripted, but it is true.

She smiles then, a small thing. I knew that girl once. She is not a girl. She is a person who stayed when she should have gone and went when she should have stayed and finally learned that the only wrong time to start is never.

“Come on,” I say. “Let’s make a map.”

We sit down in the corner with a stack of paper and a pen that writes as fast as she can speak. She tells me names and dates and while she talks, I watch the moment her voice changes from apology to testimony. When we are done, she looks taller.

“What now,” she asks.

“Now you go home,” I say. “You drink water. You scan your documents. You don’t tell him you’re leaving until the bank confirms the new account. And you call me tomorrow at nine and I tell you what to do next.”

She nods, slowly, like her neck has been asked to carry a different weight. She stands. She goes. I watch her walk through the doors into daylight that did not exist when she woke.

When the lobby is quiet again, Liam leans in the doorway with two coffees. “You look like you just remembered the word for something that’s always been there,” he says.

“Maybe I did,” I answer. “Maybe I just learned how to say it out loud.”

He hands me a cup. “We keep going?” he asks.

“We keep going,” I say. “Because somewhere, right now, someone just heard something that broke them open. They need a map.”

We clink paper cups. I think of the woman on the sidewalk, the woman on my couch, the woman in the mirror. I think of the way a room can change because one person decided the clock was wrong.

When I get home that night, the maple outside my window has decided fall. Leaves the color of old gold litter the fire escape. I sit on the bed with the window open and listen to the city do its city thing. No siren sounds like mine anymore. No door click sounds like loss.

On my dresser, a small frame holds a piece of paper I never thought I’d frame: First Light—Certificate of Incorporation. Next to it sits the little red lipstick I wore to the hearing. Next to that, my grandmother’s ring in a dish my mother bought me when I moved into my own first apartment. The ring shines its own small moonlight.

I think of Asher somewhere under this same sky, of Natalie rocking a baby to sleep in an apartment with a window she chose, of all the women I haven’t met yet who will walk into a room and sit down and start telling the truth.

I think of the sentence that began all of this—She’s pregnant, Evelyn—and I do not flinch. Sentences have power. So do the people who answer them.

I turn off the light. The room holds. The future waits, not as a threat, but as a place.

And for the first time in too long, I sleep all the way through.

END!

News

When My Husband’s Family Forgot My Birthday And Threw A Party Without Me. CH2

When My Husband’s Family Forgot My Birthday And Threw A Party Without Me Part One The note I left on…

A Local Man Was Found Dead Yesterday. It’s My Fault. CH2

Part 1 I needed to go for a walk that day. It didn’t matter that I’d been exhausted the day…

My Husband and His Boss Sneered at Me During the Team Dinner—But One Whisper to the CEO Left Them… CH2

My Husband and His Boss Sneered at Me During the Team Dinner—But One Whisper to the CEO Left Them… …

My Supervisor Deleted My Year’s Work And Said Start Over—Then The Competitors Called. CH2

My Supervisor Deleted My Year’s Work And Said Start Over—Then The Competitors Called Part One The cream-colored cursor blinked…

Heartless Husband Left Me After Job Loss, But My Success Story Made Him Regret Everything. CH2

Heartless Husband Left Me After Job Loss, But My Success Story Made Him Regret Everything Part One “You’re a burden…

Mom Let My Sister Ruin My Wedding Dress, Then Called Me Selfish—So I Revealed a Secret in My Speech. CH2

Mom Let My Sister Ruin My Wedding Dress, Then Called Me Selfish—So I Revealed a Secret in My Speech Part…

End of content

No more pages to load