My Husband Begged Me to Stay Home While He’s Meeting His Mistress in a Silk Dress I Paid For

Part One

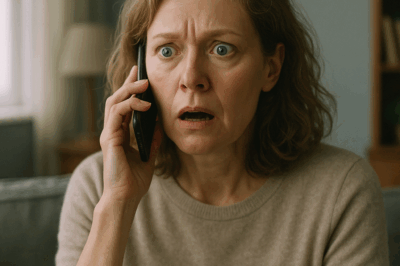

I didn’t know panic had a sound until I heard it in my husband’s voice.

“Babe, please. Just—just stay home tonight, okay?” Noah’s baritone had always been a calming ocean for me. That afternoon it beat against me like a storm surge. “There’s a storm moving in. The city already issued a travel advisory. And my mother’s migraine is back; I might need to drop medicine off later. The dinner with Cole got moved to the hotel bar anyway—no reason for you to be dragging yourself across town for nothing.”

In the background I could hear something that wasn’t his mother’s house: the polite hum of lobby jazz, an ice bucket clink, laughter that didn’t belong to me.

“I thought you said the dinner was at Beaux,” I said, glancing at the stack of invoices in front of me. The museum shop where I worked part-time was in the end-of-quarter scramble, and my brain had been tethered to budgets all day.

“It was. They moved it.” He swallowed. “Listen, you know I hate asking for favors, but this one—please, Lena. You’ve been working too hard. Draw a bath, light one of those awful fig candles, get some sleep. I’ll be late. Don’t wait up.”

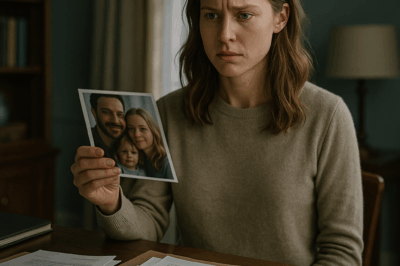

I stared at the laptop where an email subject line blinked: Your order has shipped. The sender was a boutique I couldn’t afford even on my best days. The charge—$1,260—had hit my credit card two days ago. I had nearly dropped my coffee when I saw it that morning: Mulberry Silk Bias Gown, on behalf of: M. Duvall. Gift message: Can’t wait to see you in this. —N.

Two weeks earlier, I had used the same card to pay a rush fee on the suit Noah wanted for a pitch meeting. Two nights after that, we’d had the worst fight of our marriage because I suggested we skip the hotel for our anniversary and cook at home. “The Haverford’s expecting us,” he’d thrown over his shoulder while fastening cufflinks that cost more than my shoes.

Now, the silk dress lingered in my inbox like an accusation.

“What’s the name of the hotel bar?” I asked carefully, twirling the fig candle jar, even though we both knew I hated that scent.

“What?” He laughed the way he does when he’s buying time. “Lena. You don’t need to worry about the name of a bar.”

“It’s a strange detail to avoid,” I said, pressure building behind my eyes. “You love naming things, Noah. Sneakers. Restaurants. Types of cigars you pretend to enjoy.”

He exhaled sharply. “It’s just—The Wayfarer. Okay? Jesus. The Wayfarer.”

The Wayfarer was three blocks from The Meridian, where his supposed dinner had been. The Wayfarer’s bar was famous for cocktails in cut-glass tumblers and for not minding who saw whom disappear into the sleek elevators.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll stay home.”

“Thank you,” he breathed, relief audible, and then he dropped into that voice that used to undo me. “You know I adore you, right? We’re good? I’ll bring home that tiramisu you like.”

“Drive safe,” I said. And I hung up, and stood very still, and listened to my heartbeat count the ways something was wrong.

By the time his taillights slipped around the far corner of our street that night, I had talked myself out of five possibilities. He wasn’t lying about a storm; one crawled over the Boston skyline like an animal seeking a place to sleep. He wasn’t lying about his mother; migraines had been her instrument of choice throughout our three-year marriage. He wasn’t lying about dinner—this time. He was lying about something bigger.

I poured a glass of wine because it was the prop a woman is expected to hold in scenes like this and then called my best friend.

“Put on real pants,” Jules said, not bothering with hello. “A bra if you must. Five minutes.”

She’s the kind of friend who shows up uninvited and exactly when invited, who brings mascara and a crowbar to emergencies because she knows you’ll need one or the other. She arrived breathless and suspiciously gleeful, slid into my kitchen chair backward, and said, “Start from the silk dress and don’t leave anything out.”

I told her about the email. The hotel bar. The way Noah’s voice had a shadow in it. The way Eleanor had called me that afternoon only to talk about her charity gala seating chart and slipped in, like lint between fingernails, “Be a dear and wear something refined. It reflects on all of us.”

“On a scale of one to ‘Your father will be so embarrassed’ how much does Eleanor hate your new job?” Jules asked, wiping eyeliner from my cheek with her thumb. She always asked about my job as if she loved it more than I did, possibly because she had been there when I quit a corporate role that paid me well to be well-behaved.

“On a scale of one to repent in silk,” I said. “She reminded me three times that donors prefer ‘elevated.’”

“Stay home.” Jules mimicked Noah. “Be good. Light the fig candle.” She sniffed. “Cults have better scripts.”

“Jules,” I said quietly, “I think he bought her a dress. On my card.”

“Names,” she said. “We will need names for the dramatis personae. The M. Duvall?”

“Miranda.” The person I used to copy essays from in AP Lit, who’d married a plastic surgeon and then divorced him very publicly when he slept with his receptionist. “Lives in Cambridge. Red lipstick. Sits very straight. Laughs like she knows something you don’t.”

Jules raised a brow. “How high are your heels?”

“Three inches, low stakes,” I said, wiping my palms on my jeans. “How high are yours?”

“Five,” she said. “For the idiot. Not for the topography.”

We took the T to Back Bay because there is something about descending into a tunnel and emerging somewhere brighter that makes you feel like a new person in a new scene.

The lobby of The Wayfarer was all marble and music and people who never take off their jackets. We crossed it like we belonged there—Jules because she could, me because I refused not to. The bar was to the left. I didn’t see Noah. Of course I didn’t. Men who cheat aren’t so inept they will also be punctual.

“We’re not going to find them by waiting,” Jules said. “Let’s take a walk.”

We took one. The elevators had polished doors that reflected my face back twice. The ride up was silent except for two women whispering about a remarriage. When the doors opened, the hallway was a movie set. We walked past doors with numbers and blank places where cameras probably weren’t but felt like they were.

I was about to joke that at least we’d get our steps in when the stairwell door opened at the far end and Noah stepped out.

I knew the back of his head the way I had known how many steps our stairs had. He smoothed his hair by habit. He wore the navy suit I had paid to rush because his assistant had forgotten to pick it up. He looked like himself. He looked like a stranger. He did not look like someone on his way to meet his mother.

He didn’t see us. The woman who followed him out did.

Miranda Duvall had hair like a movie and the dress I paid for floating around her knees. Her laugh came low and close. When she turned her head, she saw me watching her.

I am not violent by nature, and that’s a sentence you can only make once. The thing that flashed through me was not rage. It was relief that the ground beneath me had finally finished breaking.

Part Two

The next morning he kissed my temple like muscle memory. “Don’t forget about dinner at my mother’s,” he said. “Wear the blue dress.”

“Wear your conscience,” I said, and he didn’t hear me.

I did not forget about dinner. I arrived at Eleanor’s half an hour late, wearing a dress that made me feel like I had a spine under my clothes. Eleanor slipped out of the room the moment she saw me, phone pressed to her ear, faux-fretful voice pitched at the exact frequency to mic a performance as concern. It was a Caldwell family talent: addressing the board and ordering a roast simultaneously.

I excused myself to the powder room, took a wrong turn, and found his suit jacket draped over a chair in a makeshift office his mother kept for him. The card key was in the breast pocket. The restaurant receipt sat crumpled on the desk, the line underlined faintly in pencil: Mulberry Silk Bias Gown, charged on—. The date: last week. The message: Can’t wait to see you in this. —N.

I took a picture. I put everything back exactly where it had been. I splashed cold water on my face until I looked like a person who couldn’t possibly know what she was about to do.

“I’ll wait for him at the hotel,” I told Eleanor when I came back downstairs.

“Hotel?” she said too quickly.

“The Wayfarer,” I said. “Where he goes for his meetings.”

Her lashes fluttered the way other people’s hands do when they don’t know whether to strike or surrender. She offered to have Harrison bring the car around. “It’s raining,” she said. “And gentlemen should never arrive to a lady’s conversation with her hair ruined.”

“Thank you,” I said, and let her chauffeur me to an old life’s ruin.

Noah tried to call me on the way. I let it ring. He texted later from the hospital room where I sat with his mother’s migraines and his girlfriend’s lipstick on my skin: You’re overreacting. This is nothing.

The camera on lobby security caught me walking into The Wayfarer the same second the doorman committed the mental file of me he’d need for later. The bartender’s eyes flicked to my left hand when I asked for water. Men talked loudly around me about things that had nothing to do with me. I waited a very long time. The elevator finally sighed open. They stepped out.

He didn’t see me. Miranda did.

I did not make a scene. I thought about the dismantling required to build something else.

When the door closed behind me back home and he asked me to come back to the table—his family’s, his narrative’s—the impulse to throw champagne flutes passed and I put down my weapons.

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s talk.”

And then I called a man who once stole exams for me and returned them with corrections in the margins because he couldn’t help himself. “You graduated from being a cheater to catching them,” I told Jack when he answered. “I need you to do that for me now.”

“I charge in cash, Harper,” he said. “And I tell you if I find anything you don’t want.”

“That’s what I want,” I said.

Jack charged me five thousand dollars and my illusions. He earned both.

He found the payments to Miranda from a Caldwell trust. He found her adoption record. He found Eleanor’s first marriage certificate and the filing that made it disappear from the piles people see when they want to be certain of the world. He found the first proof of this story’s beginning and the last piece I hadn’t imagined: the fact that Noah had been paying her not just for a dress and a room but for silence.

“You don’t want to know what happened before you got to this house,” he told me when we met with the documents on the table between us. “You want to know what you’re going to do now that you do.”

“Then tell me what I’m going to do,” I said.

“Pick your war,” he said. “And your audience. And your ending.”

I picked the war where none of us died.

Eleanor’s sister believed in gossip like it was scripture and delivered it with compassion. Vivian pulled me into her old house and turned her fireplace on for a conversation that burned.

“You want the short version?” she asked. “Or the one that requires scotch?”

“Short,” I said.

“Richard married someone before Eleanor,” she said. “Eleanor married him later. Between those two events, a child was born. It cost my sister years of sleep and any interest in admitting what being a mother requires.”

“Miranda,” I said.

“Very likely,” she said. “And before you ask: no, we didn’t tell Ethan. He found paperwork after his father died and confronted his mother, but by then the foundation was formed and the story was set. And everyone was still playing their parts.”

“What was Miranda holding?” I asked. “Worth two million four years ago and more again three months ago.”

“The truth,” Vivian said. “And if you want to burn a house down, you start by telling it to people who have lived there.”

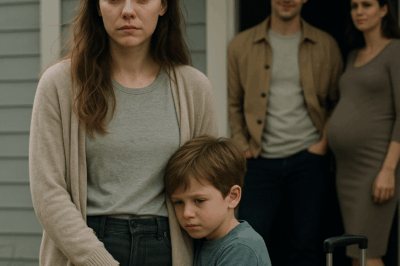

When I finally confronted Noah in his mother’s house with the documents in my hand and the ring he had bought with my money on my finger, he said something I did not expect.

“I’ve been paying her,” he said, “because the right thing costs. Not because she is mine. Because she is my father’s.”

“You could have told me,” I said. “You could have told me and we could have done this differently.”

He nodded. “I could have.”

And then his debt to the truth arrived and took a pound of flesh from his shoulder in a hotel room because Miranda needed to make a point none of us will ever forget. While he slept under morphine and Eleanor tried to pray without believing, Vivian and I convinced a woman who had been made to disappear to sit with us and tell her version of this story. She did. We did not die.

The rest moved like dominoes—slow and then all at once. The money moved from the trust into a fund with safeguards Miranda and I wrote together with a lawyer who looked like a stoic angel. The blackmail turned into a settlement that smelled more like accountability than hush. Eleanor took my hand and looked me in the eye and said, “I cannot ask you to forgive me,” which I believed was the first true thing she had said to me in three years. Vivian brought scotch.

I signed the papers that ended my marriage in a lawyer’s office with a view of a city I had earned without realizing it. I did not spend my first night as a divorcee weeping into couch pillows. I spent it writing a grant proposal for the community garden Vivian funded with her own money because she needed to fix something and this one benefited people who had not asked to be in this story.

“No victors,” Vivian said when we turned it in. “Only survivors.” Then she added: “And you.”

You will want me to tell you about revenge. Let me tell you instead about what it felt like to stand in a room full of girls at a nonprofit where I now work and see all the things I have survived look at me and wait for a cue I could finally give.

We do not always get triumph. We do not always get closure. Sometimes we get something else: a hand on a knob and the strength to open a door and say, “I am walking through this and not looking back.”

A year to the day after Noah begged me to stay home, I wrote the ending to my own story and mailed it to the court. It contained a signature and an address and a check to Jack. It contained a note to Eleanor. It contained nothing for Noah because I had nothing left to give him.

After I dropped it in the mail slot, I walked into the museum shop where I still worked because it gave me an excuse to talk about color and ask people what small beauty they wanted to carry home. Later, I went to the garden. I pressed my palm against the greenhouse glass and watched the condensation gather around my fingers and thought: this is the life I get to live now. This is the place truth took me when I followed it instead of him.

When I got home that evening, there was a box on my stoop. Inside: the fig candle I had never lit again, a silk dress return receipt, and a note in Eleanor’s slanted hand:

Sometimes men we love ask us to stay put so they can go to the places that undo us. Sometimes we stay. Sometimes we go too. You did neither. You walked away.

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

End of content

No more pages to load