My Husband and MIL Kicked Me Out After My Stroke: “You’re Useless Now!”

Part One

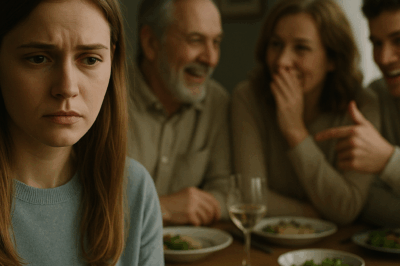

On the day everything snapped, I came home with two bags of groceries, a headache I’d been ignoring for a week, and a coupon for a brand of cereal my son refused to eat. The front door stuck the way it always had, and I had to lean my shoulder into it, the weight of a life we couldn’t afford forcing it open. The microwave clock blinked 4:37 p.m. in cheap green digits. I set the bags on the counter and closed my eyes for one full breath, the sort of breath they teach you to take in YouTube videos that promise to fix your life in ten minutes.

“Mom, I need fifty bucks for a new game,” Cassius called from the living room without looking up from his phone.

“We’ve talked about this,” I said, putting eggs in the fridge and praying none of them were cracked. “We’re cutting back.”

“Clara,” Lydia said in the tone she reserved for bankers and grandsons. She glided into the kitchen as if surfacing from a perfume ad, a frown installed precisely where it would do the most harm. “Don’t be so stingy. The boy needs to have some fun.”

“We’re barely making ends meet,” I replied. “Ethan lost his job and I’m the only one bringing in money.”

“Well,” Lydia said, with a smile that never reached her eyes, “perhaps if you worked a little harder.”

Before I could reply with something that would have ruined Christmas for a decade, Ethan sauntered in, shirt untucked, eyes glazed, the fizz of cheap beer arriving a second before he did. “What’s for dinner?” he asked like a man performing a line he’d said a thousand times to an audience that stopped applauding a year ago.

“I just got home,” I said, my patience wearing like thin fabric. “I haven’t started yet.”

“What the hell have you been doing all day?” he demanded. “Sitting on your ass?”

“I’ve been working,” I snapped. “Someone has to pay the bills.”

“So about that fifty—” Cassius, again, eyes glued to a world where lives reload in three seconds with better guns.

“No,” I said.

“But Grandma said—”

“Did you promise him money without talking to me?” I asked Lydia, who stared back at me with the satisfaction of a cat that has discovered a bird’s nest.

“The boy deserves a treat now and then,” she trilled. “You’re always so uptight.”

“I’m uptight because I’m the only one in this house who seems to care about reality,” I said, louder than I meant to. Ethan slammed his hand on the counter, the suddenness of it making a jar of pasta sauce wobble.

“Don’t you dare raise your voice at my mother,” he said.

The room tilted. A wave of pressure crested behind my eyes, my breath caught somewhere in my chest like a small animal. Black dots danced across the white tile. The grocery bag slid in my peripheral vision; apples thudded to the floor.

“Mom?” Cassius said, and for the first time in weeks I heard concern in his voice.

“I’m… fine,” I managed. I grabbed the edge of the counter. Lydia rolled her eyes.

“Always so dramatic,” she said. “Pull yourself together.”

Everything went sharp and then far away, the way things do in movies when someone is about to fall. I closed my eyes, willing the kitchen back into focus, and when I opened them Lydia was watching me unsympathetically, Ethan was scowling, and Cassius was already back on his phone.

I wanted to lie down. I wanted ten minutes in a world that didn’t require me to keep all of us alive. “I can’t do this anymore,” I whispered.

“What?” Ethan said.

I stood up straighter, clarity pooling like cold water. “I said I can’t do this anymore. Being the only adult in this house. The only person who cares.”

Lydia laughed. It sounded like money being counted. “And what are you going to do, dear? Leave? You’ve got nowhere to go.”

It was a slap because it was true. I had a sister two states away and a few coworkers who sent me holiday cards with their kids on them, but no one who could fit me and my problems into their spare bedroom the way you fit guests who remember to bring wine.

“I’m going to lie down,” I said. “Figure dinner out yourselves.”

I made it halfway up the stairs before their voices started again—Lydia’s high and insistent, Ethan’s low and angry, Cassius’s adolescent whine—and I lay on our bed staring at the ceiling fan, willing tomorrow to be different than today. I could not leave. Not yet. But I could plan. Tomorrow, I told myself, would be the first day of small, unglamorous rebellion.

Tomorrow arrived early with Lydia’s fingers in my purse.

“What are you doing?” I snapped, grabbing the bag to my chest like she was a stranger on the train and not a woman who had lived in my guest room for two years and paid for nothing but her own manicure.

“Looking for change for the paper boy,” she said, faux-innocent.

“We don’t have a paper boy,” I said.

Cassius shuffled in, thumbs moving without pause. “I need lunch money.”

“I gave you twenty on Monday,” I said. “Where is it?”

He shrugged. “Stuff.”

“Let the boy have fun,” Lydia said. “You’re always so tight with money.”

“I’m tight because we have none,” I said, my voice rising. “In case you forgot, Ethan is—”

“—not working,” Ethan said, appearing in the doorway like a storm cloud. “Thanks for the reminder.”

“I’m going to be late,” I said, grabbing my keys. “Figure lunch out. Figure dinner out. Figure your life out.”

Outside, in the car, I pressed my forehead to the steering wheel until the horn let the world know my heart. I went to work. I handled clients. I smiled at my boss. I pretended I wasn’t thinking of the mortgage payment three weeks away and the student loan payment three days away and the insomnia that had been living in the edge of my nights.

When I came home, takeout containers littered the coffee table. The sink was a monument to avoidance. Ethan was sprawled on the couch watching a game for a team he didn’t like until they won.

“Where have you been?” he asked, like I had been at a spa and not holding a department together on coffee and fear.

“Do you ever look for jobs?” I asked, dropping my bag.

“Do you ever stop nagging?” he said.

“Mom, can you not,” Cassius said from the stairs. “I’m trying to study.”

“You’re studying?” I asked, pleasantly surprised. “What subject?”

He snorted. “Why do you care? You’re never around.”

The irony of being scolded for working to provide for a house full of people who hated me almost made me laugh. I looked at Ethan to see if he had heard it. He smirked.

“You reap what you sow,” he said.

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“It means you’ve been so focused on money that you let your son slip away,” he said. “You’re a ghost in this house, Clara.”

“I’m a paycheck,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

“Will you two shut up?” Cassius yelled. “I hate this house.”

“Clara,” Lydia called from the top of the stairs, perfectly timed, a cue pulled from a play she’d been in her whole life. “All this stress isn’t good for anyone. Perhaps if you were more supportive of Ethan during this difficult time—”

“Supportive?” I said, and something inside my chest made a noise like a wire snapping. “Supportive is paying the mortgage and the water bill and pretending there’s money for the dentist when there isn’t. Supportive is packing a lunch for a teenager who throws it away and then texting the school secretary so he can get a cafeteria voucher without anyone knowing. You don’t get to redefine that word because it suits you.”

“Don’t you take that tone with my mother,” Ethan said, stepping forward. “Your mother?” I said. “What about your wife? The woman who—”

“—isn’t the only person with responsibilities,” Lydia cut in with a small smile that meant she’d found something she liked and was about to enjoy it. “You really don’t know, do you?”

“Know what?”

“Cassius,” she said lightly, “isn’t Ethan’s son.”

The room went silent. The house tilted. I gripped the chair, waiting for the floor to remember gravity.

“What?” I whispered.

Ethan’s face drained and then flushed. “Mom—”

Lydia waved him off. “And since we’re sharing, why stop there? Ethan isn’t my late husband’s son either. Men with money are useful until they aren’t.”

I stared at her. I stared at him. I stared at the wall where the wreath hung year-round because Lydia said it brought “warmth,” and I counted the red berries until my breath stopped sounding like a broken thing.

I didn’t scream. I didn’t slap her. I didn’t do anything she might have expected from a woman she believed lived entirely on emotion. I went upstairs. I put my laptop in my bag. I put the one photograph I wanted—Cassius at five, first day of kindergarten, hair sticking up like a plan that didn’t know it wouldn’t work—in another. I came back downstairs.

Ethan grabbed my arm. “Clara, wait. We can talk about this—”

“Get your hand off me.”

“Think about Cassius,” he said.

“I am,” I said. “I always am.”

“Leave,” Lydia said crisply. “And kindly take your drama with you.”

“My stroke,” I would think later, “began that night.” Not in my brain—a bruise you can see on a screen—but in a life so tight it had cut off circulation to pieces of myself I hadn’t thought about in years.

I slept in the car because I couldn’t think of anywhere else to go where I wouldn’t hear Lydia’s voice through the walls. In the morning, I showered at the gym I paid for and never used. I went to work. I was very professional. I did not cry in the bathroom. I did not tell anybody. I went home because houses have a pull even when the people in them do not, and I went straight to the bathroom to wash my face and tell myself all the things the Internet tells you to say: You are strong. You are enough. You are—

The world went sideways. My left arm became someone else’s. The words in my mouth forgot how to be words. I stumbled, my head hit tile, and then nothing.

When I swam up again, the world had a beeping soundtrack. A woman in scrubs with a name tag that said Dr. Patel stood at the foot of my bed. “Mrs. Thompson,” she said gently. “You’ve had a stroke. A minor one, but we need to keep you a few days.”

“Clara,” I corrected thickly. “Not Mrs. Thompson.”

“You’re lucky your husband found you when he did,” she said.

Lucky. The word made me think of Lydia’s face when she smelled my thrift store perfume.

“When can I go home?” I asked, panic rising. If I wasn’t home, who would keep the lights on?

Dr. Patel frowned. “You’ll need rest. No work for at least two weeks. Low stress. No heavy lifting, literal or metaphorical. You need to prioritize you.”

There is a special place in hell for the phrase prioritize you when rent is due.

The door opened. Ethan came in first. Concern flickered across his face and then settled into annoyance. Lydia followed, awareness of good lighting inherent in her stride.

“So,” Ethan said. “What’s the plan? When can she come home?”

“When she can come home,” Dr. Patel said, “depends on when you can make sure she doesn’t cook, clean, or handle stress.”

“We have bills,” Ethan said. “We can’t afford for her to lay around.”

I stared at him. I stared at the woman who had made him like this. “Get out,” I said.

Ethan blinked. Lydia’s mouth twitched. “Clara, don’t be—”

“Out,” I said, the word finding its balance. “Both of you.”

After they left, Dr. Patel sat. “Do you have someone to call?” she asked.

“My sister,” I said. I hadn’t told Rachel any of the worst parts of my life because younger sisters are for pretending and protecting. I called anyway.

“Clare-bear?” she said, long-distance worry in her voice. “What’s wrong?”

“Can I—” I said, and the rest of the sentence came out like a flood.

She arrived when I was discharged, the same small fierce person who used to punch bullies in the fourth grade and then hold my hand while I cried. We drove west because she lives where the streets are wide and the sky is visible. My phone buzzed until the battery protested. Lydia left voicemails that would have been funny if they hadn’t made me physically ill: “We’re concerned about your mental state, dear. This behavior isn’t stable.” Ethan texted: We need money for Mom’s medication. Cassius wrote things I can’t bring myself to type.

“Turn it off,” Rachel said. “Turn all of it off.”

At her apartment, she fed me soup the color of gentleness and introduced me to Sarah, a lawyer with a spine like steel and earrings shaped like daggers.

“That,” Sarah said after I told her everything, “is financial abuse. You’ve been coerced and exploited, and the stroke didn’t happen in a vacuum. We’re freezing accounts. We’re filing for divorce. We’re getting a restraining order. We’re going to make sure you can breathe long enough to heal.”

It took three days to disentangle my money enough to stop the bleeding. Three days for Lydia to show up at Rachel’s building and pound on the door while shouting up the stairwell that I was abandoning my family. Three days for Ethan to pretend to cry in the lobby and tell me he couldn’t even afford pizza for Cassius—a teenage boy whose appetite had turned into an expensive way to be furious.

I opened the door on the fourth day because the noise wouldn’t stop. “You can’t just leave,” Ethan said, mask of sweetness discarded, eyes sparked with a fear I recognized: no more ATM.

“I didn’t leave,” I said. “I escaped.”

“You selfish—” he began.

“Don’t,” I said.

“Think about Cassius,” he said, and the way he said our son’s name made me wish words were knives. “He needs you.”

“He needs therapy,” I said. “He needs the truth. He needs you to be better.”

“You owe us,” Lydia said over his shoulder. “We took you in.”

“You moved into my guest room,” I corrected. “And then into my marriage.”

Rachel stepped between us then, small and lethal. “This is a restraining order,” she said, holding up the paper we had filed and a judge had signed because in America some pieces of paper still mean things. “You will respect it.”

In the weeks after, Lydia told everyone with a Facebook account that I had gone mad. She said I had abandoned my family. She told people at church that I had fabricated the stroke to get attention. She called my boss. She called my mother’s sister, who cried (of course she did) and sent me a hand-written note with a twenty-dollar bill tucked inside like the past.

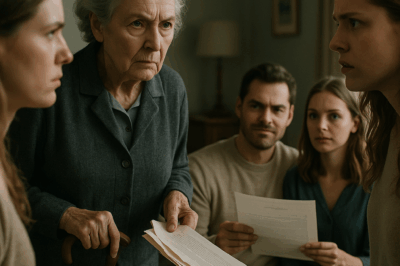

We went to court. Lydia wore mourning to the first hearing as if someone had died. Ethan wore a suit that didn’t quite fit. Sarah wore the kind of authority you can’t buy.

Ethan’s lawyer painted me as unstable. He said the stroke meant I couldn’t think clearly. He said I’d always been poor with money, poor with time, poor in judgment. He said Ethan and Lydia should be entrusted with our finances while I recovered.

Sarah stood. “Your honor,” she said in a voice that made the room lean forward, “what my client has survived is not simple marital discord. It is a years-long pattern of coercion and exploitation. We have records.” She laid them out: the second mortgage I hadn’t known about, the cash withdrawals that correlated exactly with Lydia’s spa appointments, the credit cards in my name that had been used to pay for hotel rooms I did not sleep in. “And we have a doctor,” she added, “who will testify that the stress contributed directly to Mrs. Thompson’s stroke.”

Then she pulled the pin that blew up the Lynches’ performance.

“We also have evidence,” she said, “that large sums have been siphoned from joint accounts into an offshore account controlled by Mrs. Lydia Thompson. The deposits correlate to withdrawals from an estate that belongs not to Mr. Thompson’s father—as has been represented—but to the biological father Mrs. Thompson had an affair with in the 1990s.”

The courtroom murmured like a body waking up.

The judge banged his gavel. Lydia’s face did something I will remember when I am ninety: it turned, for a split second, into what she looks like when she isn’t performing. Ethan’s jaw dropped. He turned to his mother with the expression of a boy who has just watched a magic trick explained and realized he never knew what he was seeing.

We recessed. In the hallway, Ethan approached me.

“I didn’t know,” he said. He looked like a man whose map had been burned.

“I believe you,” I said. I did. “It doesn’t change anything.”

“Cassius,” he said. And there it was: a father finally saying his son’s name like something he wanted, not a weapon. I looked past him. Cassius stood at the end of the hall, taller and older and more lost than he had any right to be. Lydia materialized, of course she did, grabbing his arm and pulling him around the corner. “Don’t listen,” she hissed, loud enough for me to hear. “She’ll turn you against us.”

Back in the courtroom, the judge spoke slowly. “Mrs. Thompson,” he said to me, “you will assume sole control of your earnings and accounts. Mr. Thompson, you will be removed from all financial instruments until this case is resolved. Mrs. Lydia Thompson, you will surrender your passport. I am instructing the District Attorney to open an investigation into potential fraud.”

“Order,” he said, and banged the gavel again as Lydia rose and turned on her son.

“This is your fault,” she hissed. “You never should have let her—”

“Mom,” he said softly. “Enough.”

Walking out of that courtroom did not fix my life. It did not fix my brain. It did not teach my hands how to stop shaking. But it turned something in my chest back on.

The hardest part came after. Five years of after.

Part Two

Grief, they never tell you, is not always for the person who died. Sometimes it’s for the life you thought you had. Sometimes it’s for the version of your teenager who still liked pancakes on Saturday.

In the first year, there were days I didn’t think I would make it to bedtime without crying in the grocery store. There were days I ate soup and watched TV and took my meds and didn’t look at my phone and called that a win. There were days I worked and worked because work has rules and people say thank you. There were days I hated everyone. The body remembers how to heal in increments. The mind resists and then gives in. The heart keeps its own timeline.

Sarah got me the divorce with enough in it to prove the law sometimes cares. Half the house—which I sold; I never wanted to sleep under that roof again. Restitution from Lydia’s offshore account, which dribbled in because wealthy men in tropical countries do not comply quickly. A restraining order that had to be renewed twice because Lydia believes rules are for other people.

Rachel taught me to sit on her balcony and drink coffee without feeling like I was wasting time. She introduced me to friends who didn’t know the Lynches, and I learned the pleasure of being a person again and not a role. On a Tuesday I will always love, she took me to a ceramics class where we made bowls that were not perfect and I didn’t care.

Cassius didn’t speak to me for almost three years. He sent a string of texts after the judgment, each more vicious than the last—Lydia listening just off screen, no doubt, telling him which words would hurt most. My therapist told me to write him a letter every month and not send it. I did. I wrote about the weather and my job and a song I heard on the radio that reminded me of the way he danced at six. I wrote about money and about pride and how they tangle. I wrote, always, that I loved him in a way that had nothing to do with blood and everything to do with pancakes on Saturdays.

Lydia left. Of course she did. She had always been a migration more than a mother. One day my attorney called to tell me that the District Attorney had indicted her on charges of fraud, tax evasion, and “something creative involving shell companies.” She didn’t show up for court. There was a rumor she’d been spotted in Bali with a man who sells jewelry to tourists and secrets to the wrong people.

“The justice system,” Sarah said, with the weary cheer of a woman who has watched it fail as often as it works, “has a long memory.”

I moved to Los Angeles because Rachel said I would like the light. I did. I rented an apartment with a balcony that faced the sunset and a kitchen counter that fit exactly three plants and a cutting board. I made a rule that I would turn my phone off at nine and turn it on at seven and that I would not answer numbers I did not recognize unless I felt brave. I bought a rug. I bought new sheets. I bought a dress that was not practical. I had coffee with people who loved me.

Five years to the week after the judge said the word investigation, my phone rang.

“Mom,” the voice said, deeper, exhausted. “It’s me.”

I had imagined this call a thousand times and every version of it included my hands shaking. They didn’t.

“Cass,” I said. “Are you okay?”

“No,” he said. “Can I come over? Dad’s with me.”

Fear and something that used to be hope did a complicated dance in my chest. “Yes,” I said. “I’ll buzz you up.”

They looked like the aftermath of a storm. Ethan had gray in his hair and a humility I hadn’t seen since we were twenty-two and he still said please to waitresses. Cassius stood in my doorway six inches taller than the last time I’d seen him and so much less angry it startled me.

“Come in,” I said, and the words didn’t feel like a betrayal anymore.

They sat on the couch like people waiting for a verdict. I sat in the chair Rachel had given me when I moved. I can’t explain the surge of Elation I felt at the fact that my living room didn’t smell like beer.

“We need help,” Ethan said, always the opener. “We’re… not doing well.”

“Grandma,” Cassius said, and something in me bristled because I had a lifetime of hurt attached to that word. “She—she took everything. Dad’s inheritance. The house. The car. We thought she was—” He stopped, swallowed. “She’s gone. Some island. We have nothing.”

I suppose I could have said I told you so. I suppose I could have said go to the woman who told you your mother was a liar. I suppose I could have said a hundred sharp things that would have tasted delicious for ten seconds and like ash for weeks. Instead, I said, “I’m sorry.”

Ethan stared at his hands. “We… made terrible choices. We believed her because it was convenient and because she made being angry at you easy.”

“Why are you here?” I asked gently. “You have to decide that before I can decide anything.”

Cassius looked up. It was like looking at a photograph of an infant and a man at the same time. “I want to go to school,” he said. “For real. Not because Grandma wants to brag. I need… I need help.”

“Okay,” I said. “Here’s what I can do. I can help you apply for scholarships. I can co-sign a loan if I have to. I can let you use my printer when yours runs out of ink at midnight. I can’t give you cash.”

Ethan looked like he wanted to argue. He didn’t. “And me?” he asked. “Do I get a punishment or a plan?”

“You get both,” I said. “There’s a program. Retraining for adults. Not glamorous. Pays eventually. You’ll be exhausted. You’ll feel less important than you’re used to feeling. You will have to be okay with that. I’ll give you the number. I won’t call for you.”

He nodded. It surprised me. He looked old. He looked like someone’s son.

They stood to go. Cassius lingered. “I’m sorry,” he said, his voice cracking in a way that made me think of broken things growing back into trees. “For what I said. For everything.”

“I know,” I said. “I love you.”

He looked startled, like he thought that would be complicated now. It wasn’t. He hugged me. It felt like the ghost of age five and the reality of age twenty-one, and both made sense in my arms.

When they were gone, I stood at the sink and breathed and cried and laughed all at once. Rachel called because she always knows, like sisters do when you share a childhood and the way a mother liked her coffee. “There’s a headline,” she said. “You’re going to enjoy it.”

I opened the link. Lydia’s face filled the screen, a glamor shot next to the words ARRESTED IN BALI. Expats in forums used words like grifter. The article mentioned an offshore account and the phrase extradition pending. I made a sound that could have been a laugh or a sob or both.

Karma is a lazy word. Justice is an inconsistent friend. But sometimes both dress up, hold hands, and take a walk on the same day.

I took my coffee to the balcony. The city stretched out, pockets of orange and pink stitched in like blessings at the end of a long letter. I thought about the woman who had pressed a finger to her temple in a hospital bed and promised herself she would leave. I thought about Lydia’s voice in my kitchen and my own voice in a courtroom and Cassius’s voice in my living room. I thought about money and how it is such a poor measure of the people who look rich. I thought about pancakes. I laughed.

Rachel texted: To beginnings.

I wrote back: To continuings.

I stood, warm air on my face, and knew—not like a hope, like a fact—that I was not going to be okay.

I was going to thrive.

END!

News

My Family Called Me Their Rock—Until I Heard Them Call Me Their Golden Goose. CH2

My Family Called Me Their Rock—Until I Heard Them Call Me Their Golden Goose Part One The first time I…

My Brother Married My Best Friend And Tried To Take My Inheritance, Until Grandma Stepped In. CH2

My Brother Married My Best Friend And Tried To Take My Inheritance, Until Grandma Stepped In Part One The cream-colored…

My Husband Left Me For My Best Friend, But Their Wedding Day Held An Unexpected Surprise. CH2

My Husband Left Me For My Best Friend, But Their Wedding Day Held An Unexpected Surprise Part One The text…

My Best Friend Stole My Husband, But I Discovered Her Secret That Would Destroy Everything. CH2

My Best Friend Stole My Husband, But I Discovered Her Secret That Would Destroy Everything Part One I still remember…

My Husband’s Family Rejected Me For Being Poor, But A Year Later Our Paths Crossed Again… CH2

My Husband’s Family Rejected Me For Being Poor, But A Year Later Our Paths Crossed Again… Part One The words…

My Best Friend Crashed My Anniversary With a Bombshell About My Husband’s Betrayal, So I Set a Trap. CH2

My Best Friend Crashed My Anniversary With a Bombshell About My Husband’s Betrayal, So I Set a Trap Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load