My Husband and In-Laws Plotted to Steal My Family’s Millions: “She Just Needs the Right Push”

Part One

I didn’t hear the beginning of the conversation—just the sentence that tore the picture off the wall and left the nail dangling.

“She just needs the right push,” Reed was saying, that smooth, confident tone he saved for clients and campaigns. “If we can convince her to quit teaching, she’ll have to rely more on her parents’ support.”

I had come down from checking on our daughter after her nap—Lila’s breath light as milk in her toddler bed—to find my scarf, and I froze as if the hallway runner had become a trap. The voices carried from the living room in that way voices do when they assume the house is on their side.

“Darling, you’re being too subtle,” my mother-in-law, Camille, purred. She’d spent thirty years climbing a social ladder by rubbing her skin raw and calling it grace. “That salon chain her mother runs is worth millions. Sloan needs to understand that her little music-teaching thing is beneath her potential.”

Their little what? The cheap punch of it took a second to land. Teaching wasn’t how I made money; it was how I breathed. Bach in small hands and tiny triumphs when a piece finally sang—those were the riches nobody could put in a spreadsheet.

“It’s not that simple,” Reed said. There was a sigh in there that I hadn’t heard before. “She’s stubborn about her independence. She gets that from her father.”

“Well, her father isn’t getting any younger,” Grant—Reed’s father, whose eyes could weigh people like produce—grunted. “Neither is her mother. Have you looked into their estate planning?”

Something ugly moved in my stomach. Mom and Dad were sturdy people. Mom managed twenty-three salons in three counties and still kept pretzels in her office drawer because stylists forgot to eat. Dad left the tech company he founded because he liked tinkering in his garage more than boardrooms, then invented a cooling system for hair dryers and gave the patent to Mom because it delighted him to think of it in her hands. They were the opposite of a windfall waiting to happen. They were a storm you learned to walk in.

A floorboard groaned under my foot. The living room fell silent for half a beat; then I heard glasses chime.

I took a breath like a diver does, walked into the doorway, and rearranged my face into a smile I reserve for catching students passing notes. “Hey,” I said. “Having a nice chat?”

Three faces turned with three different sets of instincts: Reed’s millionaire-charm pasted on and just beginning to peel at a corner; Camille’s charity-ball smile stiff with triumph; Grant’s pleasant blankness that only ever broke for Dickensian statements about hard work and “respectability.”

“We were just talking about your career,” Reed said, the crease between his eyebrows appearing—the one that showed up when a pitch didn’t land.

“Anything interesting?” I asked, picking up my coffee mug simply because my hands needed work.

Camille clasped her hands, letting her diamond speak. “Darling, we were discussing how many more opportunities you’d have if you weren’t tied down to… the school. With your family’s resources—”

“My family’s resources,” I said, and tasted the iron in it. “Are exactly that. My family’s.”

The room softened for a second and then hardened. Reed started to say my name. I held up a hand.

“Would you mind watching Lila for a bit?” I set down my mug precisely where it wouldn’t leave a ring. “I need air.”

I caught my reflection in the hallway mirror as I reached for my keys: same messy bun, same favorite sweater, same woman who high-fived a seven-year-old for getting through “Minuet in G” without tears. But someone else looked back, too—someone who had just realized the ground under her house might be cork, floating on water, and she had better learn to swim.

“I didn’t think your father would actually come,” I told Mom later, laughing a little. “But he brought his tablet.”

Mom laughed, too. We were at their kitchen table, the one I’d scraped my knuckles on helping Dad refinish ten Thanksgivings ago; Mom sliced stems off peonies as if they’d wronged her. My heart had stopped trying to climb out of my chest twenty minutes earlier only because the smell of her tea and Dad’s aftershave had stunned it into staying.

“You’re quieter than usual,” Mom said without looking up. “Everything okay with Lila?”

“She’s perfect,” I said. “She’s with Reed at his parents’. They wanted to talk about a business venture.”

“Camille and Grant,” Mom echoed, and the way she said their names made me sit up a little straighter. Mom does not dislike people lightly. She keeps grudges in a Tupperware in the back of her freezer and brings them out only if company deserves them. Three years ago when I married Reed, she had offered her best set of dishes while saying to my father in a tone she thought was private, “He’s glossy. Let’s hope he’s kind.”

“He asked that you and Dad come,” I said. “More investors, I guess.”

Dad looked up, the rim of his reading glasses leaving a moon on his nose. “What kind of venture?”

“He said property development,” I said. “Guaranteed returns.”

Dad’s mouth did a thing it does when he’s too polite to snort.

The doorbell rang. Through the window I watched Reed walk up the path, smile set to wring out every advantage, his parents hovering a step behind like people who always stood at podiums even when they sat.

Lila wasn’t with them. “Where—”

“The nanny is watching her,” Reed said, kissing my cheek. “We thought it better to discuss without distractions.”

We sat through dinner like people playing a board game with hidden stakes. Camille complimented Mom’s roast and slid in barbs that would take twenty-four hours to dissolve. Grant steered conversation toward retirement. Reed watched Mom and Dad the way men watch markets. At some point my hands stopped shaking and I began to take notes in my head for a lesson plan I would never teach: “Microaggression and Macro-Agenda — a case study.”

“We wanted to bring an opportunity to you,” Reed said finally, placing his glass down as if he were laying a gem. “Premium location. Guaranteed returns—”

“And you’re bringing this to us because—?” Dad asked pleasantly.

“Because family should help family,” Camille chirped, shooting me a glance like a thrown knife. “And with your resources—”

“Our resources,” Mom said, not raising her voice, “are allocated to the new locations opening next month.”

Reed’s smile faltered then reattached itself with a poorer adhesive. “Diversification—”

“Returns,” Mom said, and he set the one word down like a ball he hoped she wanted to pick up.

“Better returns than the business I built from nothing?” Mom asked, and I remembered how her hands looked years ago when she took out a loan with a cosigner who didn’t have her last name. “Better returns than being able to pay our employees in a pandemic? Than putting our daughter through college without debt?”

“That’s not what we meant,” Camille said, quick, because this was not going to plan. “We just think—”

“I know exactly what you think,” I said, surprising myself by how calm I sounded. “You think my parents’ money is your backup plan. You think my mother’s business is a stepping stone to something shinier. You think I should quit teaching, fold into the family firm like a good drapery, and let my husband handle the finances.”

The air in the room got cold. Reed looked at me with something flat behind his eyes. He opened his mouth. I made a decision.

“I think,” I said, standing and letting my chair scrape, “I need to choose my family.”

I left them staring at the end of the table where I had been. Reed followed me to the foyer. “We’ll discuss this at home,” he said. The tone was meant for bending, not for breaking.

“No,” I said. “We won’t.”

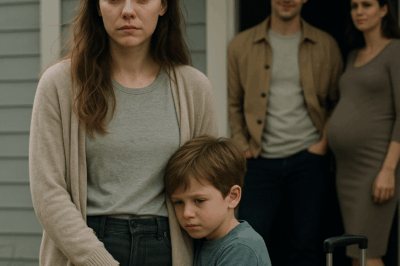

I slept at my parents’ that night. Lila snored softly in Mom’s sewing room surrounded by a thousand spools of thread. In the morning, I made pancakes with Dad and told him I’d listened to my husband and my in-laws talk about my parents’ estate like it was fruit ripening on a tree. Mom’s knife didn’t slip; she cut through an apple with the precision she reserves for expensive hair and lazy arguments. “Don’t be sorry,” she said. “Be smart.”

Midnight made bad ideas look like the only road out of town. I was on the floor in our study with Reed’s laptop in my lap, the good rug under my knees, the house making familiar sounds that had forgotten how to comfort me.

The password was still my mother’s birthday. The sweetness of it didn’t just sour—it curdled into a shape I recognized: manipulation that looks like intimacy until it asks you for insurance information.

At first it was the normal ugliness: credit card balances that belonged on other people’s books; PayPal receipts for “consultant” fees that were almost certainly to people named Kayden or Stone; email subject lines that used words like opportunity and leverage that made the back of my neck itch.

Then I opened a folder labeled Family.

The contents made my mouth dry: spreadsheets showing small transfers from an account tied to Mom’s business to a shell company with Reed’s initials. An email thread with Camille moving from baby talk to business with terrifying ease: any progress on getting into Marlo’s systems? If we could pivot a line item or two no one would notice for months. Reed’s responses were exactly what you think they were.

A floorboard creaked. I didn’t turn my head. You treat a snake differently if you can see its head.

“Looking for something?” Reed leaned in the doorway like a fallen ad for watches.

“How long,” I asked, my finger still on the trackpad but my eyes on him, “have you been planning to steal from my mother?”

He tried to smile. For a second, the effort looked like it hurt. “Steal is such an ugly word.”

“No,” I said. “Embezzle is an ugly word. Steal is the story you tell Lila when she’s old enough to ask where this went wrong.”

He came into the room, ran a hand through his hair like a commercial for contrition, and sat on the edge of his desk. “Do you know,” he said softly, “what it is to live under a family like yours? Everything I do is measured against the metric of Marlo and her empire. Your parents never have to take risks because they have a net. My parents never taught me what a net was. I built everything myself.”

“You built it on paper and confidence,” I said. “And when it rained, you cut a hole in my mother’s roof.”

He slammed his palm down. I let myself jump so he could see I wasn’t made of brick. “I am drowning, Sloan!” He gestured to the mess I had neatly made. “That property development fell through. I owe people money they do not forgive. Your parents sit on a pile and watch me sink.”

“You could have told me,” I whispered, and the words felt like the ones that hurt, not the ones that win.

He looked at me with something like pity. “You never had to ask about money.”

“Because Mom taught me to build a life that didn’t require running from it,” I said. I forwarded myself everything. I cc’d my lawyer before my thumb could shake.

“What are you doing?” he asked, and there it was—the flicker of fear I had been waiting for.

“Protecting my family,” I said. “You have twelve hours to tell my parents everything. Then I do.”

“You’re bluffing,” he said, and in that moment I wondered for the first time if he had ever known me at all.

“Try me,” I said, and went upstairs to pack Lila’s backpack with a dragon and the good snack cup.

He tried to stop me at the door, fingers on my wrist too tight, and he would probably spend the rest of his life telling himself he hadn’t meant to grab me hard enough to bruise. “It’s the middle of the night,” he said. “Don’t do this.”

“Let go,” I said, calm as the hallway rug.

For once he did what I asked.

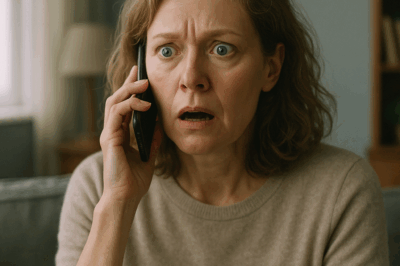

Bad news didn’t arrive like a sequel; it came like a trilogy in the same day.

Before dawn, my lawyer called to confirm that Reed had emptied our joint savings account. Legal, because both names were on it. Perfectly ghoulish, because he had done it at a time of day that convinces a teller you are buying a house or running away. When she asked if I wanted to freeze the remaining accounts, I laughed, and she said, gently, “I can do it for you.”

At noon, Mom had a stroke. She collapsed on a salon floor while showing a new manager how to close out the till—her handwriting stuttering across the training form like a song she suddenly couldn’t remember. Dad called from the ER with his voice pitched an octave lower than he knew: “She’s stable. They’re saying the next forty-eight hours are important.”

Just before midnight, my phone buzzed with an unknown number and a picture of Reed walking out of a hotel with Camille, a manila envelope tucked under his arm. The caption read: thought you should see this.

By the time Dad came back from the coffee machine, I had made and unmade four terrible plans. He handed me a cup that tasted like burnt plastic and hope. “The vultures are already calling,” he said, which is Dad for your mother is unconscious and Camille is still Camille. “Maria called me—she took the phone off the hook in the back room because it wouldn’t stop.”

“Mom told the managers?” My throat hurt.

“Of course she did,” he said. “She trusts them. She trusts you. Which is why she—” He pulled his tablet from the inside of his jacket. Documents glowed on the screen like a lighthouse. “She transferred the majority control of the salons to you last month.”

I exhaled hard enough to see it. “She—what?”

“She said she had a feeling,” he said, smiling like a person walking into the dark with a good flashlight. “That woman’s instincts could have made a fortune on Wall Street if beauty hadn’t kept her.”

A rumble at the nurses’ station made us both look up. Reed was arguing with security with an earnestness that would have sold a thousand toasters. Camille hovered behind him, her hair perfect in a way that spoke of chaos contained by mousse.

“Sir,” the guard said, “only family.”

“I am family,” Reed insisted. “That’s my mother-in-law in there.”

I stood. Dad grabbed my arm. “Let security do their job.”

“No,” I said. “Let me do mine.”

Reed saw me coming and put on the concerned-husband face. “Sloan,” he said, spreading his hands. “I’ve been so worried.”

“Which hotel did you stay at tonight?” I asked. “Or are we being subtle?”

For a second, something moved across his face—fear? calculation?—then the salesman smiled arrived late and left early. “We were meeting counsel.”

“What documents did you review with your ‘counsel’ at the Grand?” I asked, pulling the photo up on my phone. “Property papers? Salon accounts? Dad’s patents?”

He blinked. “Sloan—”

Dad stepped up beside me, his calm like a cloak. “Tell me, Reed,” he said, and the gentleness in his voice was something only people who had never made him angry mistook for weakness. “What do you think you know about my work?”

Security took them before it got louder than a hospital should be. Camille hissed something that was probably supposed to be devastating in the lobby; Reed let himself be guided away with one last look back that might have been regret in a person with different wiring.

I went to the bathroom and threw up. Then I washed my face and came back to watch Mom breathe and made God, who I still wasn’t sure I believed in, a promise I knew I would keep: I will hold the line you’ve built. I will not let them turn you into a story about debt instead of a story about making things.

Part Two

Three days later, I stood at Mom’s desk with the salon mirrors reflecting an empty chair behind me. On the screen in front of me, numbers told a story I did not like: small “temporary reallocations” that weren’t temporary; then larger ones that should have been flagged if anyone had had the audacity to question Reed’s authority. Maria, the head stylist who has been with Mom since the first shop when it was Mom, a rented chair, and a lot of coffee, knocked and poked her head in.

“They’re here,” she said, her mouth twisted. “You want me to pretend you’re not?”

“No,” I said. “Let them see.”

Camille and Grant came into the office like they were being filmed. “Sloan,” Camille said. “Your mother’s asked us to—”

“Sit,” I said, without looking up. “Or don’t. The chairs are comfortable.”

They sat.

“I hear you’ve found the accounting issues,” Grant said, in the tone of a man asking a waiter for a check.

“I found your signatures,” I said, turning the laptop around. “On transfers from Mom’s accounts to … an entity I haven’t seen before. Care to introduce me?”

Camille smiled with all her teeth. “You’re stressed,” she said. “And with your mother’s illness—”

“Stroke,” I said. “You can say it.”

“—it’s only natural to feel overwhelmed,” she continued. “That’s why we’re here. To take some weight off your pretty shoulders.” Her ring flashed. “Reed has experience in leadership.”

“Reed has experience sending money to himself and labeling it ‘temporary reallocation,’” I said. “And you have experience telling him how.”

“Now, there’s no need for language,” Grant said mildly.

“Language is my job,” I said. “And business is Mom’s. You don’t get to talk like ethics because you own a blazer.”

Camille crossed her ankles. “We could make this go away,” she offered. “Quietly. You sign over controlling interest, Reed runs day-to-day while your mother recovers, and we—”

“Make yourselves rich,” I said. “I’m good. Thanks.”

“You don’t want to do this,” Grant said. “Think about the investors. Think about hair in the headlines. Think about—”

“My daughter?” I asked. “Because someone already did.”

Camille’s mask cracked. Only for a second. But it did. “If you were to be so bold as to threaten our family,” she said softly, “I wonder what a judge would think about a heated woman who throws things.”

“Security footage?” I asked. “You really want to play me at that table?”

She stood. “You have twenty-four hours to be reasonable.” She smoothed her skirt and smiled for a photographer who wasn’t there. “Choose wisely.”

After she left, the office smelled like shattered crystal and perfume. Maria placed a cup of tea on the desk the way you place a hand on someone’s shoulder when you know better than to hug. “Your mother would be proud,” she said.

“Not yet,” I replied, and pulled my laptop closer. “But she will be.”

I didn’t just record our confrontations. I wrote a play. I cast it. I built a set.

I told Reed to meet me at his parents’ house. I told him I wanted to stop fighting and compromise—for Lila’s sake, so she could see her grandparents without a court order dictating which hours were acceptable. When I arrived, the study looked like a courtroom: Camille and Grant behind the desk, Reed at the head of the table, a laptop open with footage from his office playing on loop—me throwing the crystal award, a frame without sound where they could write their own captions.

“Where’s Lila?” I asked.

“With the nanny,” Camille said. “This is not a conversation for children.”

“Agreed,” I said. I put my own laptop on the desk and opened a video chat window. On the other end, my father’s lawyer nodded. Maria sat beside him in a high-neck blouse I’d only ever seen at funerals, fierce as a blade. And Thomas, Grant’s former business partner, joined with a chime. Grant’s face struggled to remember how to be bloodless.

“Hello, Grant,” Thomas said. “Been a while.”

“What is this?” Camille asked.

“Business,” I said. I slid a USB drive into my laptop and shared my screen: real records, not the ones Reed had prettied up for himself; transfer histories with account numbers that matched my mother’s books; an email thread in which Camille typed move 5k from marketing—she never notices that number and hit send. Then Thomas shared his—creative accounting methods employed, maybe, in an old venture, where money had become lax and morals had taken at bath and slid down the drain.

“This is illegal,” Camille said.

“This is evidence,” I said. “And this is the deal: you sign confessions that return every penny, you sign a legally binding agreement to stay away from the salons, from Mom’s patents, from my father’s hard drives, from my daughter. In exchange, I do not send this to every three-letter agency on the East Coast today.”

“And if we refuse?” Grant tried.

“Then,” I said, “you get famous in a way that karate classes and charity boards don’t fix.”

One by one, hands shook. One by one, signatures landed like gavel falls. When we got to the divorce papers, I handed Reed a pen and rested my hand on the line labeled custody. “Full,” I said. “And supervised visits until a judge I trust says otherwise.”

“Please,” he said. And in it I heard the boy who wore a tie with ducks and believed he could sell salad dressing to a carnivore. “Can I still—” He looked down. “See her?”

“Get help,” I said. “Not the Instagram kind.”

He signed.

I left without looking back, because the only way to leave a room like that is without giving it your face to remember.

They underestimated me. Maybe because I teach kids to bow after they finish a piece and praise each other’s courage. Maybe because I loved their son and smiled at Thanksgiving and let them assume my spine was a decoration. Maybe because they thought “good girl” meant “easy mark.” That’s the thing about women like me. Our kitchens teach us patience. Our classrooms teach us planning. Our mothers teach us war.

Six months later, my mother’s office no longer felt like a room waiting for someone. She sat in her chair for the first time since the stroke and tapped the desk with a knuckle. “It’s crooked,” she said in a voice that had relearned its own shape, pointing at a crooked picture on the wall. “Who put that there?”

“Reed,” I said, straightening it. She rolled her eyes and then smiled. “How does the right side of your mouth feel today?” I asked, and she stuck out her tongue because she preferred not to answer questions directly.

Maria leaned in the doorway. “Your four o’clock is here,” she said. “Do you want me to send him in?”

Reed walked into the salon in jeans and a shirt he hadn’t used a credit card to buy. He held a folder and something else I almost recognized.

“I don’t need your money,” I said before he could speak.

He shook his head and set the folder on the desk. “Loans,” he said. “For small businesses. Grants for expansions. There’s a program that could help with the three new locations you put on hold. I’ve vetted it. I’m not selling it to you. I’m giving it to you.”

“Why?” I asked. Some days I was capable of irony; today I was not.

“Because I owe you more than jail time would repay,” he said without looking away. “Because Lila asked me if her grandmother was a superhero, and I told her the truth—that you were cut from the same cloth. Because I finally have a job where lying gets you fired instead of promoted.” He breathed out, and the word hung in the air like something expensive you finally paid for. “Because I’m trying.”

I took the folder. It was exactly what he said—thorough, clean, useful. “We’ll send it to counsel,” I said. “No strings.”

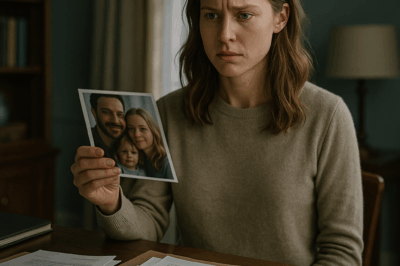

He nodded. He reached into his bag and pulled out a photograph in a frame as cheap as the hotel where he’d met Camille. Mom stood in it, a ribbon across her hair, scissors in her hand at the opening of her first salon. My twelve-year-old self hovered just outside the frame, visible only in the reflection of the storefront window—brown eyes wide, looking in.

“She built something,” Reed said, setting the photo on my desk. “You did too.”

When he left, I looked around the room. Mom’s notes were all at right angles. My coffee had gone cold. The picture was straight now, and so was the part. The loan program would help. The salons would expand. The tech patent Dad had given Mom would fund a grant for stylists who wanted to own their own chairs. And my daughter would grow up learning that strength looks like staying when it’s hard and walking when it’s necessary, like handing someone the folder they need rather than the apology they didn’t ask for.

“Staff meeting,” Maria said, tapping her watch.

“I’ll be right there,” I replied. I sent a text to my father with a photo of Mom pretending to scowl at the crooked frame. I sent another to my in-house counsel: Review loan program. Reed brought it. Then I stood, straightened my jacket, and walked into a conference room full of women who call me by my first name and never once by girl.

As I passed the salon mirror, I caught my reflection. I didn’t look the same as I had in the hallway outside my living room that Sunday. But everything important had, finally, moved into its right place. Behind me, the rooms were full of noise I had chosen: dryers and laughter and the low hum of women who know their own value.

Out front, a little girl waited for her grandmother with a superhero cape around her shoulders because she liked how it felt when it moved. When Lila saw me, she lifted the cape high so it fluttered and asked, “Did you fight any bad guys today?”

“Only on paper,” I said.

She looked relieved. “Can we have pancakes for dinner?”

“Yes,” I said. “We can have whatever we want.”

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

End of content

No more pages to load