My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”

Part One

“Is it Kennedy? It’s me, Aaron.”

Ten years of silence should cauterize a voice. It didn’t. The moment I heard the gravelly drop at the end of my ex-husband’s sentences—the same drop that used to come when he’d say I’m late and mean I’m lying—my stomach did the old reflexive twist.

I was at my small kitchen table, graded literature quizzes stacked to my left, a chipped mug of green tea steaming the edge of a to-do list to my right. Outside, a sparrow hopped across the tiny concrete square my apartment lease calls a balcony and teachers call a blessing. I’m sixty now, a part-time teacher at the private school that took me on when I retired, partly because I’m a decent educator, partly because I know where the backup staplers live, and partly because the students call me “Ms. D.” the way I used to call my favorite teacher “Mrs. B.” and it makes the years fold in on themselves like a fan.

“What do you want?” I asked, the way you ask a fly what it wants when it insists on circling your head.

“You’re living in your parents’ house now, right?” Aaron said, as if he hadn’t disappeared with my son’s wife a decade ago, as if please and sorry were optional punctuation. “I know it’s sudden, but could you… leave? Like, move out? We need a place.”

Silence has weight when it sits on your chest. Mine felt like two hands, unkind and familiar.

“Leave my parents’ house,” I repeated.

“Seeing that you’re still there,” he went on, unbothered by my incredulity, “you haven’t remarried, have you? So just—move. Haley’s pregnant. Having a kid is more expensive than we thought. We’re struggling. Everett turned us away. My parents are being stubborn. Everyone’s so petty.”

I pictured his father’s stiff back, his mother’s rigid smile, his brother’s knotted tie the day I first visited their house to introduce myself thirteen years before Aaron and I married. This call wasn’t the worst they’d weathered, but it would certainly not be the one that softened them.

Ten years fell back on me like a coat. I put it on and felt the old weight. Then I took it off. I have learned, in the decade since my marriage ended like a door slamming, that you do not have to carry what someone else hands you. That day, I set the old coat down.

“Unfortunately,” I said, “my parents’ house is gone.”

“What?” he said, and for the first time in the conversation a human note entered his voice—a crack of confusion.

“My father died three years ago, my mother last year,” I said. “I sold the house. Too big for one person. Too full of ghosts who deserve better than to be pushed around by people who don’t know how to say grace.”

A beat. Then: “Dead,” he said, flat, as if the word were a checkmark. “What about the inheritance?”

There it was. His voice didn’t even disguise it—only his patience did. He wanted to know, not if I was okay, but if there was anything he could access that wasn’t nailed down by decency.

“All the money from my parents’ estate went to me,” I said carefully. “Along with the house.”

“That’s not fair,” he blurted. “You can’t— They liked me.”

My parents had loved me enough to do the hard thing. Ten years ago, when Aaron and Haley vanished with a divorce form on my kitchen table, my father, angry in a way that made his silence louder, and my mother, brittle with grief, had sat at their dining room table and signed papers at the lawyer’s office. Their will said, in stark legal prose, what my father couldn’t say to Aaron without throwing something: we will not leave a penny to the man who eloped with our son’s wife.

I could have explained that. I could have told him how my mother cried into a tea towel the day she penned the final letter to the lawyer, how my father stared at the old photograph of Aaron holding our son at his fifth birthday and shook his head, like a man trying to dislodge a terrible story from the end of a fishing line. I could have told him how I stood on the front lawn of the only house I grew up in, locked the door, and put the keys in an envelope with the forwarding address of the young couple who were going to paint the master bedroom a color my mother would never have considered. Instead, I said only:

“It’s done. It was done years ago.”

On the other end of the line, something rattled. “You don’t mess with me,” he snarled, as if volume could undo a will. “There’s no way that’s allowed.”

“It’s legal,” I said. “And moral.”

“Dead,” he said again, muttering now. “No house. No money.” He exhaled, then, as if he were losing air from a hole he hadn’t noticed. “So what are we supposed to do?”

“We,” I repeated, and the sparrow outside cocked its head like it, too, couldn’t believe it. “I don’t know what you and Haley are supposed to do, Aaron. I know only that I am not your plan B.”

He hung up. I sat very still at my little table and watched the tea bloom brown in the water. I’ve learned in ten years to let myself sit, in moments like that, until my heart has slowed enough to let my head do what it is good at: think.

It’s odd, the way memory can feel like a single blow when in real time it was a long series of small taps. I met Aaron the way people used to meet in stories like these—at a tutoring center where I worked part-time to pay for textbooks and his older hands, clumsy with eagerness, made me laugh at how careful he was with the fax machine. He was older, but I had been there longer. The director asked me to show him how to lesson plan for bruised egos and long evenings. We started dating. We pressed our foreheads together against the window glass of a city bus and agreed I would major in education, he would find a steady office job instead of chasing freelance work, we would be an ordinary family, the kind that goes to the community pool on Saturdays and reads on the sofa on Sundays.

We were married three years after we met, and our son Everett was born with fists like punctuation marks. He was bright and restless and built worlds out of cardboard. He went off to study design in New York, fell in love with a sculptor named Haley, brought her home to meet us with the flush of someone who thinks seeing and keeping are the same verb. We toasted their happiness with cheap sparkling wine because joy doesn’t care about your budget.

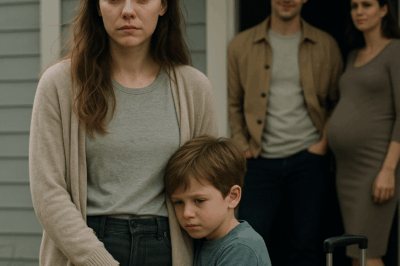

Ten years ago, Everett came home and sat across from me, his face pale in a way that made me feel a mother’s terror at once. “Mom,” he said, voice shaking. “You’re married to Dad, right?”

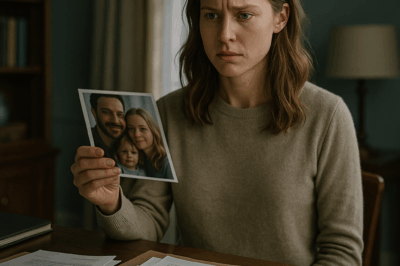

It was the sort of question whose answer does not need to be spoken but must be, so the person asking can believe they have not lost their mind. I nodded. He showed me a photo on his phone of Aaron and Haley walking arm in arm into a hotel near the music district, the kind with a lobby that smells like oranges and cash. He had tried to follow them, had seen enough to know his eyes were not lying, and had come home because he is the sort of man who thinks the truth, no matter how brutal, deserves sunlight.

I confronted Aaron that night. He tried to lie, the way he always tried first, but he had eaten and the alcohol made his tell too obvious: he looked down and left when he lied. He admitted it. He said he had been swayed. He said he and Haley had started “dating” six months before. He said he was in love. Then, without waiting for me to catch up to his gall, he said he wanted to marry her.

The divorce was a form on a table and a suitcase, and then nothing. They disappeared into the city the way people do when they believe anonymity is a form of absolution. I sold the house, eventually, not because the mortgage demanded it, but because the echo demanded something else. I moved into a smaller place near the school, the size a person needs when all she owns that matters fits in boxes labeled Books, Photos, Kitchen, Everett’s First Shoes. I taught, I graded, I sat with freshmen and said, “This is what a thesis is” the way my favorite teacher had said to me when I thought writing was a kind of alchemy for other people. The work steadied me. The students—god bless the unpredictable, sincere, hungry way teenagers are when they aren’t trying to be liked—healed me.

Everett threw himself into the work of his hands. He stopped sending me photos of sculptures for a while, then started again. He stopped calling for an hour every Tuesday, then called for five minutes every day. He would say, “I’m okay,” in the way a son says to a mother, I can’t be honest yet—and then one day, he said, “I met someone. Two kids. A woman who knows how to hold things. Like me.”

And then the phone rang ten years later with Aaron asking me to get out of my parents’ house so he and Haley could move in, and I learned you can be both shocked and un-surprised at once.

Two hours after Aaron’s call, my phone rang again. “Kennedy?” a voice said, soft and angry at the same time. “It’s Haley.”

I said nothing.

“You could’ve told me they died,” she said. “Your parents. How could you not tell me? I was family.”

“If you were family,” I said evenly, “you would have visited before they died.” I waited for a beat. “Or after.”

Silence. Then, a sputter of words that weren’t grief, but greed in a dress that thinks it’s grief. “You’re so cold. You just want the money for yourself. You always were selfish.”

I hung up. I am too old to teach empathy to people who don’t see the equation.

An hour later, Everett called. “They tried me too,” he said. “Showed up here. I told them I would call the police.”

“Are you okay?” I asked. “Did they—”

“I’m fine. But I have an idea.”

He laid it out, the way artists sometimes reveal their practical streak when necessity presses on them like a hand. “I hired a private investigator,” he said. “It’s not just Haley.” He paused. “There are others. Seven, at least. Married, three of them.”

I listened. I took notes. I felt the old ache of humiliation on behalf of a younger me who thought Aaron’s worst habit was forgetting to take out the trash.

“Let them meet each other,” Everett said. “I’ll send them the address.”

The address. He had it. The private investigator had earned his fee in hard facts and photographs that made my mouth taste like pennies. They were living in a building with peeling paint and plastic plants in the lobby that were less honest than the real ones would have been because deception is always tackier than grace.

Two days later, the phone rang again. “Kennedy,” Aaron shouted, a confusion of sounds behind him: a woman crying, another screaming, a man’s voice saying he was calling the police. “What have you done? They’re swarming—”

“Who?” I asked, polite as a Sunday school teacher.

“Women,” he said, uneven breath whipping the word into a sharp, embarrassing flag. “Seven. You— You told them—”

“No,” I said. “They asked. Someone answered.”

In the background, I heard Haley: “Seven? I knew about two. Seven?”

“You’re impressive,” I said, because sometimes pettiness is a balm as healing as bandages. “Truly. You’ve been busy.”

“Don’t hang up,” he yelled. “Don’t—”

I said the thing I had waited a decade to say, in the voice I use when I need ninth graders to stop throwing paper airplanes and start learning the difference between a simile and a metaphor: “Goodbye, Aaron. Please never show up in front of me or our son again.”

I hung up. I blocked the number. I wrote a note to myself on a Post-it and stuck it to the edge of my laptop: When he calls from a new number, do not answer. I made tea. I graded a stack of essays that used the word “awesome” too liberally and “because” not enough. I slept.

Part Two

The story of how a man who ran away with his son’s wife asked his ex-wife to move out of her late parents’ house has a satisfying ending in the genre of tidy morality tales: public disgrace. Police reports. Lawsuits. People receiving envelopes from lawyers and learning that decisions are not photos you can delete when they no longer flatter you.

It’s true. The fallout came swift. The husbands of the three married women he’d been sleeping with filed suit. Haley, who had imagined she was the only star in a redemption arc, realized she had been cast as an extra in a film that does not pass the Bechdel test, and left—though not before calling me to say I had ruined her life, to which I said, “I told you to stop painting the wrong door.” Loan sharks are not a trope when you watch a woman get into a car with two men who don’t feel the need to introduce themselves. Aaron—jobless because companies like the kind he used to work for do not love headlines with the words affair, son’s wife, police, and apartment disturbance in them—moved between couches and benches and, finally, according to a colleague’s careful tone, a park.

But that’s not the part that interests me.

I am sixty-one now. Age does not make you wise by default; it only gives you time to practice the habits that either make you wise or make you brittle. I try to practice this: when someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time. I did not, once. I do now.

I kept teaching. On Tuesdays, I run the after-school writing lab where fourteen-year-olds who think they hate the five-paragraph essay learn that form is a kind of liberator. On Wednesdays, I buy a dozen bagels and a tub of cream cheese, because no one should have to diagram sentences on an empty stomach. On Thursdays, I grade until my eyes blur and then I put on joyful music and cook something my mother used to make—meatloaf, tuna noodle casserole, things with names that taste like the whole of an era—and invite my neighbor, who moved in last winter and who thinks part-time teachers are saints, even though we both know we’re just people who didn’t figure out how to stop needing what we love.

Everett comes for dinner on Sundays when he isn’t at a workshop or dancing to music in a kitchen with the woman he met, who has two children with the exact right amount of chaos between them. The first time he brought them over, the boy looked around my apartment, picked up a silver frame with a photo of me and Everett at a county fair when he was ten, and said, “Is this your dad?” I laughed and told him no, that was my son. He blinked, then nodded like this was a reasonable plot twist, and went back to his Lego spaceship.

“What do you think?” Everett asked me that night when the dishes were done and the kids were putting on their shoes very slowly because children are very bad at saying goodbye quickly when they’ve decided your home is safe. He meant What do you think of her. He meant Am I allowed this second chance?

“I think,” I said, “it is a beautiful thing when people who have been hurt find each other and don’t make an altar to pain.”

He nodded. He kissed my cheek. He took the leftover pie even though I told him twice to leave it and come take it tomorrow because everyone knows pie is better the second day.

A week after the great apartment brouhaha, I ran into Aaron’s mother in the cereal aisle. I did not turn my cart around. I did not wave. I stood beside the oatmeal and waited to see which version of herself she would bring to me.

She curled her fingers around the handle of her cart like it was a relic. “I heard,” she said. “I heard you sold the house.”

“Years ago,” I said.

“And the will,” she added, like a woman trying out a word for the first time. “It left everything to you.”

“My parents,” I said, “were very clear about their wishes.”

She looked at the Quaker man on the oatmeal box as if he would volunteer legal advice. “We didn’t raise him for this,” she said finally.

“I know,” I said, and didn’t add, and you also didn’t stop him. Because there is a difference between truth and weaponry, and I am too old to lob the latter at people whose arms are already weak.

“Be happy,” she said then, abruptly, as if the words were a coin she had found in her pocket and decided to spend before it fell through a hole. “He made you unhappy. Fix it. It is the only revenge that sticks.”

I laughed, surprised into it by the accuracy. “I have been practicing,” I said. “Thank you.”

The fall turned to winter. The private school put on a production of Our Town, because teenagers have a sixth sense for material that will make their mothers cry. I sat in the back row and watched a girl in braids tell a boy in suspenders that she loved him. I watched another girl in a colonial bonnet die and realize that pouring syrup on pancakes in our kitchen once upon a time was joy disguised as ordinary. I cried. I went home and made pancakes for myself for dinner and ate them in my slippers at the kitchen table, because there are luxuries that are not about money.

Aaron called from a new number in January. “Happy New Year,” he said, as if we had a tradition.

“Do not call me again,” I said.

“Everett doesn’t answer,” he blurted. “Tell him—”

“No,” I said, and hung up. I blocked the number. I did not explain. I did not post about it on the internet. I did not call a friend to say, You will not believe—. These are the small choices that make peace possible. They are not dramatic, and they will never get you an award.

Spring arrived and with it, a class of seniors who looked at me with that hollow-eyed panic that says college feels like a cliff and not a bridge. I told them what I always tell them: you have taught me as much as I have taught you; the world is bigger than you think and not as big as your Instagram makes it out to be; be kinder than necessary, which is to say, be precise with your kindness, not stingy; call your mother; call your father; call someone who won’t expect it and say the thing they have always wanted to hear from you.

On the anniversary of the day my parents signed their will, I went to the cemetery among the maple trees, pressed my palm against the cool stone, and told my mother I was learning to bake her pound cake properly—a teaspoon of almond extract, not a tablespoon. I told my father I had found a stapler in the bottom drawer of the filing cabinet at school and felt the old teacherly thrill of the hunt. I told them I had done the thing they asked of me: I kept what they gave me safe from a man who didn’t know how to hold it.

If this were a different kind of story, I would end with a parable. But I prefer receipts. So here is mine: the apartment is in my name; the school keeps renewing my contract; my son loves a woman who loves him back; I am fine; I am also happy, which is not the same thing; I am learning to dance with these students’ joy and their fear, and I am letting them teach me how to be young without being foolish.

And when my phone rings with an unknown number, I make tea and let it go to voicemail. If it is a student, I call back. If it is the bank reminding me to sign the thing I always forget to sign, I sign it. If it is a voice I used to live with, I delete the message without listening. You are allowed to live your life, I remind myself, without inviting yesterday to sit on your couch.

The good ending is not that Aaron got what he deserved; it is that I did. It is that in the wreckage of one family, another shape formed—my son in a kitchen, stirring sauce with a woman who knows the weight of two lunch boxes; my students leaning against my desk asking if the semicolon is “fancy” or “annoying”; the quiet pleasure of finding out I am better at being sixty than I was at being forty.

Aaron once told me, the last year we were married, that I was living in the past, as if nostalgia were a disease. I live in the present now. It fits. It wasn’t built for two, but it holds me. And when I sit at my small table, graded papers in a neat stack, tea cooling beside a Post-it that says Grade Emma’s essay first (a different Emma, this one fourteen and precocious and fond of adjectives), I sometimes think of the call where a man told me to get out of my house, and I smile, not because cruelty is funny, but because I get to choose how the story ends.

He said get out.

I said no.

And then I said nothing at all, and that was the most powerful sentence I had.

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls ‘Help with the Funeral!’ Me – ‘My MIL died 3 years ago’. CH2

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls “Help with the Funeral!” Me — “My MIL died 3 years ago.” Part…

End of content

No more pages to load