My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar…

Part One

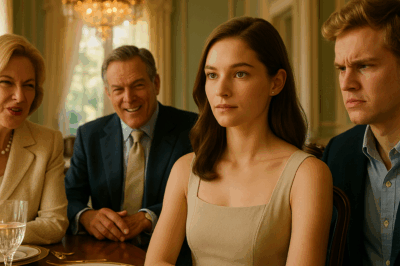

The pen clacked against the glass table and every nerve in my body split into bright, electric threads. I’d thought I was prepared for anything—Ursula’s syrup-sticky smile; Victor’s patrician stare; the house manager hovering with linen napkins in case anyone’s outrage spilled. I was not prepared for clause 7.1.

Any and all assets acquired during the marriage shall be considered the sole property of Quinton Wellington III upon acquisition… In the event of dissolution, the wife waives any and all rights to support, alimony, equitable distribution, and/or claims against Wellington family entities and trusts, regardless of contribution.

“You understand it,” Ursula said, tapping a lacquered nail at the signature line as if I might’ve missed it between the flourishes. Her drawl, the kind cultivated in drawing rooms where the thickest books are interior design volumes, filled the cavernous living room. “We simply must protect family legacy.” The last two words came out in boldface.

Across from me, Quinton looked at his hands. Or rather, at his shoes. Italian leather, hand-burnished. I had once loved the way he cared about details. I had once confused polish for character.

“Just paperwork,” he said at the rug, avoiding my eyes. “My parents insist on a prenup. Everyone does it.”

“This isn’t a prenup.” I kept my voice even; business school teaches you tone is half the negotiation. “This is a deed of gift. From me. To you.”

He flinched and then recovered with his newest habit: the pleading half-smile I had first seen when he needed me to reschedule a site visit so he could make golf with a client. “Please don’t make this a thing, Nat. We’re three days out. Sign it and none of this matters.”

None of this mattered. And yet here was his mother timing my breath to the second hand on her diamond-crusted Cartier. Here was his father swirling scotch like a weather system and watching for cracks in my resolve. Here was their attorney in the doorway, posture neutral and eyes hungry.

I slid the papers back across the table. “You’ll want to give me some time,” I said, and watched Ursula’s shoulders loosen in victory. “It’s a lot to take in.”

“Of course,” she cooed, triumphant. “You’ve never dealt with documents of this… sophistication.”

Victor chuckled into his crystal. “We’ll need it back by tomorrow. The church won’t hold dates for the uncertain.”

The church. Saint Helena’s with its river of light through stained glass. The aisle where I had imagined the faces that had loved me: my father’s hand grease-stained but tender, my mother’s eyes bright with a teacher’s exact pride, the scholarship donors whose belief carried me to an Ivy while I worked the library after midnight. A different legacy. One I could breathe in.

I didn’t fight in their living room. I took the folder, gathered my coat, and walked into Charleston’s gold-limned evening. The air tasted like salt and coming rain.

Back in my apartment, the one with floors I refinished myself and art I chose without anyone telling me what had provenance and what didn’t, I dialed the number I swore I wouldn’t need.

“Rachel,” I said when my attorney answered. Behind her I could hear the murmurs of a firm that had outgrown its origin story. “We’re moving up the schedule. Ironclad, now.”

Rachel didn’t ask what happened. She had been building contingencies with me since Quinton suggested we “combine accounts for simplicity.” She had named each protocol like a hurricane. This one we’d christened IRONCLAD because it left no seams to pry. In three hours she and a small army of clerks had transferred every property, every equity holding, and every tangible asset that I wanted to remain mine into an irrevocable trust with me as grantor and my godmother as trustee. The trust had a quirky, unmistakable name I’d chosen in a moment of defiance: Magnolia Stone. Something deep-rooted. Something both soft and unbreakable.

Then I called Gabrielle, our wedding planner. “Change my RSVP,” I said.

There was a beat of silence. “Natalie… you’re the bride.”

“I’ll be attending, Gabrielle. As a guest.”

“You can’t.” Panic crackled down the line. The Wellingtons were donors to the historical society that managed the church and the reception site and possibly the city’s weather. “They’ll—”

“Order extra champagne,” I said, and hung up.

Charleston put on her prettiest face for the wedding. Saint Helena’s doors were thrown wide like an embrace I no longer wanted. Magnolia branches arched over the steps. Ursula had leaned into the theme with ruthless charm: pale roses in arrangements that towered like heralds; a string quartet so precise they could have been a metronome; ushers in tails as glossy as the grand piano’s sheen.

Guests turned as I entered. I had traded the white gown for a cream sheath with a neckline that would make news photographers argue about whether it was bridal or a declaration of independence. I did not bring a bridesmaid. I brought a clutch with a copy of the prenup under a Forbes magazine whose cover I had not authorized but for once was perfectly timed: The Southeast’s New Titan: How Natalie Evans Built a $29 Million Real Estate Empire Before 30. My team had planned the story for after the honeymoon. A junior editor with Sussex ancestors and an omniscient sense of drama had moved it up when word of the Wellington wedding hit their radar.

Whispers rustled the pews like a breeze through palmettos. Ursula came for me like a storm, pearls quivering at her throat. “What are you wearing?” she hissed. “What are you doing?”

“Following your instructions,” I said, holding up the unsigned prenup. “Sign or the wedding is off, remember? You wrote that line yourself.”

She blanched so quickly I almost stepped back, the way you do when a wave collapses at the wrong moment. Victor descended from the altar like a general abandoning the lines to fix the optics himself.

“You little—” He caught himself, glanced at the bishop, smiled in a way that made the skin around his eyes turn reptilian. “My dear, you must be overwrought.”

“Overwritten,” I said, and lifted the magazine. The photographer had caught me at my desk, all glass and iron and an exposed brick wall my contractor had argued against because “new money loves brick.” The headline did its cinematic work. Victor’s eyes flicked. Then narrowed. Ursula’s lips parted. Somewhere behind them, at the altar, I could feel Quinton go still in the particular, horrifying way of a man who realizes his Plan B has been an illusion.

“I’m attending,” I said, handing the prenup to Ursula like a scrap of paper a teacher passes back with try again in the corner, “as a witness to your son getting everything you wanted. Except me.”

The quartet faltered, recovered, and kept playing like good professionals. The bishop looked as if he had been forced to redirect lightning. Vanessa, Quinton’s sister, knocked her champagne against a pew so hard it shattered into glittering shards and amazement. I walked back down the aisle alone—no bouquet, no veil—out into the light. It wasn’t triumph I felt. It was clarity, the kind that aches.

By the time I reached my car, my phone had become a device exclusively for Wellington panic. Where are you. We can talk about the prenup. We’ll change clause 9. My parents didn’t mean— Please. I love you. There was a time those words would have reached into my sternum and rearranged the furniture. I blocked every number with my thumb moving as steadily as a metronome.

I drove out of the historic district, past the Battery where couples took engagement photos against cannons and history and a harbor that held more ghosts than anyone cared to name. I crossed the bridge, the cooper’s hawks circling in the updrafts. I put the magazine on my kitchen counter beside an orchid that refuses to die despite my schedule and the fact that I keep forgetting to rotate it toward the sun.

For a day, the city talked. They said cruel things and kind things and things that made me want to send bouquets to strangers who had chosen compassion without context. The Wellingtons went to ground—their house shuttered, their yacht inexplicably busy with “maintenance.” An assistant at the Post & Courier called Rachel, who said the phrases no comment and we wish the family the best in three languages. She sent me a screenshot of the prenup with certain lines highlighted and the message: They hired a tax attorney to write a marriage contract. It reads like a leveraged buyout. You saved yourself from a hostile takeover.

A week later, I dropped a check at the cash buyer who had been circling a lot I wanted for a mixed-use project. I wrote “for Magnolia Stone” in the memo line and felt something in my sternum relax. A week after that, I installed Rachel’s firm as outside counsel to two of my partner companies and watched our legal bills become surgical instead of bludgeoning.

I told myself the story was done. Of course it wasn’t. Anyone who’s ever renovated a hundred-year-old house knows the walls always hold a surprise.

It was Quinn who returned. Not in person at first. He is, for all his weaknesses, not a man who chooses the battleground his parents prefer. He sent an email whose subject line was my name and whose body held the halting honesty of a person writing to the version of himself he wants to be.

I’m sorry.

I loved you and I was a coward.

I let them negotiate my soul for me.

I understand if you never want to speak to me again. But please let me say what I should have said then: I would have built a life on your terms. I am starting to build a life on my own.

The piece of me that still remembered the first night we sat on my roof with takeout and argued about whether Haussmann saved Paris or gutted it was tempted. I wrote a reply that said, We can’t rewrite the first act from the third. Then I deleted it and asked Rachel to send his lawyer a mutual release of claims and a reminder to stop using a picture of me in his portfolio of philanthropic images.

He sent a final email with a photo attached. Not of the church or the yacht or the house of closed shutters. Of King Street at night, lit like theater. I hope you keep rebuilding what you want to see in this city, he wrote. You were always doing that. I was always walking around thinking the buildings were permanent.

The thing about old money is people think its walls are bulletproof. But most legacy houses are mortgaged to the rafters. Most yachts are leased. Most family names are brands some intern manages on a social media calendar. When you step away without letting them sink hooks into your flesh, you blow a hole in their mythology. They cannot forgive that. But they cannot prevent it from being true.

Part Two

Two months after Saint Helena’s, Magnolia Stone closed on a parcel that had been a hazard two hurricanes ago. It was cypress stumps and city code violations and a view of a marsh that was worth a thousand angry donors. I walked the perimeter with my contractor, Jules, who carries a measuring tape like a sword and knows where every underground line lies by instinct.

“We’ll put workforce housing above the storefronts,” she said, squinting at the fall of the light. “Do what they should do and pretend they came up with it.”

“We’ll put a daycare in the corner space,” I said, and she grinned because it’s easier to keep carpenters on a job when somebody on the crew grew up in a house where you could nap on-site and no one would call you an inconvenience.

We hired a dozen people whose resumes said things like self-taught and second chance because my ledger has two sides and only one of them is numbers. The first time we poured a slab, the clouds rolled in so fast I thought we’d be baptizing concrete into the Cooper. The crew kept working. When the rain came down it made the site smell like iron and possibility.

I set a rule at Magnolia Stone: we do not pretend profit is the same as virtue, and we do not pretend virtue is allergic to profit. The city came at me with a thousand small knives—permits delayed, inspectors with a taste for theater, a councilwoman who wanted the corner unit for her nephew’s concept bar. I brought them all to the site and walked them through the second-floor framing where two boys—one whose father taught him to swing a hammer without hitting his thumb, one whose mother taught him to stand back and look at his work like it was a mirror—argued about whether we should shift a window six inches to get better morning light. Humans bend. The daylight mattered. So did the electrical plan. We moved the window.

I saw the Wellingtons twice in that first year. Once in the society pages where the caption private family celebration said more loudly than any scandal coverage could have, and once at a charity gala where Ursula kept one hand on a chair back as if the room tilted when I entered. She wore pearls that could anchor a yacht. I wore a dress with ribs that matched my spine.

“Natalie,” she said, voice pitched to friendly for the camera angles. “You look… well.”

“So do you,” I replied, and we both understood the rule of the game: we would be gracious in rooms built on the backs of people who had never been invited into them. Then we would leave and do more consequential things.

Vanessa wrote a column in a glossy that apologized for Charleston’s “recent uncouth turns toward a new class of entrepreneur.” She didn’t mention my name. She didn’t have to. If you know a house by its porch, you know an insult by its furniture. I didn’t reply. The city knows who paints over rot and who pulls up boards.

The real reveal came not at an altar but at a closing table.

Rachel called me on a Tuesday with a voice like a bell. “Victor’s family office has a balloon payment due on a line of credit they took to buy those hotel parcels on Meeting Street,” she said. “The lender is calling the note unless they can refinance. The bank would have done it—if their tax attorney hadn’t written their consolidation agreements like an estate plan.” I sat down because certain kinds of schadenfreude make you dizzy. “Magnolia Stone can buy the debt at a discount,” she continued. “If you want to be the poet the city quotes in a decade, this is your sonnet.”

We bought their paper quietly. I called a meeting at their office, where everything is mahogany and professional silver frames around photographs that pretend time is linear. Ursula sat next to Victor because she knows optics and sympathy cameras do not forgive distance. Quinton’s chair was empty. Vanessa wore white in the way only the guilty do when they’re in denial.

I slid a file across the table. “Your lender has sold your debt,” I said. Time slowed down, the way it does when a chandelier decides to remind everyone where it came from. “To me.” I laid the assignment of loan documents on the polished wood. “Per section fourteen, subsection c, I can either restructure your terms at my discretion or foreclose on the properties securing the line.”

“You wouldn’t.” Ursula’s voice was breathless. “It would be… uncivilized.”

“On the contrary,” I said, soft because true things don’t need decibels. “It would be precisely the civilization you wanted me to respect.”

Victor looked at the legal language like a foreigner who refuses to admit he’s in the wrong airport. “You planned this,” he said.

“No.” I shook my head. “You taught me to finish things.” I gestured toward the window, where the skyline had the audacity to change without permission. “And the city is a better student than you think.”

We did not foreclose. I am not a vandal. We wrote terms that prepaid four years of wages to the cleaning staff and servers who had been laid off in cycles that perfectly matched the Wellingtons’ fundraising seasons. We attached conditions that required affordable housing above any future wells of champagne. We placed a seat on their board for a person who answered to nobody named Wellington. We built a covenant into the loan that reinstated default if any family member who had been in the room during the prenup tried to use marital status as a financial tool again. Rachel named the clause 7.1 for a private laugh.

Victor signed like a man swallowing a fish bone. Ursula pressed so hard the ‘U’ of her signature left an indent. Vanessa posted a photo later with a caption that would have made literary critics weep for the metaphor: Rising together, grateful for visionary partners. The city’s comments were kind and cutting. You cannot build in public without inviting a chorus.

Quinton sent me one sentence that night: Thank you for not burning the house down. I responded with none.

I thought often, in those scraps of quiet the day leaves if you take them, about the moment at the church when I held up that magazine like a shield. It hadn’t been my plan; the cover story had been the work of a PR firm and a photographer with an eye for light and a writer who liked to write about founders who didn’t look like founders from thirty years ago. But it turned out that the only way to end a myth is to replace it with a better story. The city needed to see a woman in a cream sheath dress unmoved by a banker’s temper. It needed to watch her cut a ribbon at a mixed-use building with a daycare on the corner where a bar was supposed to be. It needed to hear her say, at a council meeting, “Profit and decency are roommates. You can’t evict one without making the other late for work.”

Six months later, Magnolia Stone hosted its first tenants’ breakfast. We used the same caterer the old hotels used for weddings because fried green tomatoes taste like truce in any room. A young woman in scrubs introduced herself and told me she had moved in with her son after sleeping in her car behind a florist shop for two weeks. “I got my job back because of childcare downstairs,” she said, then looked me straight in the face the way Quinton never could and added, “We pay rent on time. That’s dignity too.”

There were rumors that the Wellingtons would leave Charleston. Some said Savannah. Some said Palm Beach. Some said they had chosen to stay and reinvent with missionary zeal. I didn’t keep close track, the way you stop checking your ex’s social media because your nervous system grows allergic to that kind of attention. What I did hear, through channels it is better not to name, was this: Ursula met with a therapist who didn’t take her insurance. Victor learned how to check his own bank balance. Vanessa stopped writing apology essays for a magazine where you can count the number of Black women who have been on the cover with your fingers and a repentant heart.

A year to the day after the non-wedding, I met Rachel for drinks at a bar with no back room and a pianist who played “Moon River” because you can’t escape your geography. She ordered a martini that looked like a course in its own right and clinked my glass. “To ironclads and brick,” she said. “To knowing where to swap the blueprint for the wrecking ball.”

“And to prenuptial agreements written like love letters because there are some we would sign,” I added, and she grinned because we both knew that in a better world, a contract is a promise to leave each person better, not poorer.

There’s a coda, because there always is. It arrived as a note on heavy paper with my name in a hand I recognized from thank-you cards Ursula had thrust at me after charities delivered our photo to the society page. It said:

You were never one of us, and you never needed to be. I’m not sure if that is an apology or an admission. Maybe both. We will not meet again in a room where we must pretend. Please accept my hope that we will live in a city improved by your stubbornness.

—U.

I folded it into the back of my copy of The Death and Life of Great American Cities and put it on the shelf beside the deed to Magnolia Stone. Not because I forgave them. Because my archive tells the truth as well as the ledger.

People ask me, sometimes at the end of panels on development or before elevator doors close or over the cheese course at dinners where I remember I taught myself how to hold a wineglass with two fingers because some rooms won’t let you in unless you look like you belong, if I ever plan to marry. I tell them: “I’m writing my prenup before I write my vows. It will say my worth is not transferable. It will say my assets are my own. It will say the house I built will have a window left open, but the deed will remain in my name.”

When the right person laughs—not cruelly, not nervously, but with kinship—I take a second look. Until then, I walk through my city with my boots on the ground and my eyes on the cornices, noting what needs mending and what needs tearing down and where the light falls best at nine in the morning on the corner of Meeting and Broad. The air smells like possibility. It smells, faintly, of magnolia and iron and a woman who chose to write her own contracts.

If you’ve stayed with me this long, maybe you were looking for instruction. Here it is: The altar is any place you realize you have been invited to worship the wrong god. Step away. You will be told you are dramatic, ungrateful, unladylike, unwise. You will be told that paper is rude and emotion is unseemly and money is a language you were not born to speak. Learn it anyway. Speak it fluently. Then use it to build houses where other people get to keep their keys.

I did not marry a Wellington. I married Charleston to a version of itself she was not brave enough to imagine until a woman in a cream dress made her look in the mirror. And on some mornings, when the marsh grass lies down in the wind like a secret finally told, I think: this is how legacy ought to feel. Not like a deed someone forces you to sign. Like a city deciding, in public, who it wants to be.

END!

News

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… CH2

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… Part One The…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… CH2

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… Part One The…

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… CH2

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… Part One The emergency room’s…

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead. CH2

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead Part…

End of content

No more pages to load