My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street…

Part One

The certificate in my hand felt insubstantial as tissue paper. It had the heft of effort but none of the gravity required to bend light in our living room. The regional business competition award I’d been excited to share an hour earlier now looked like construction paper dressed in formal clothes.

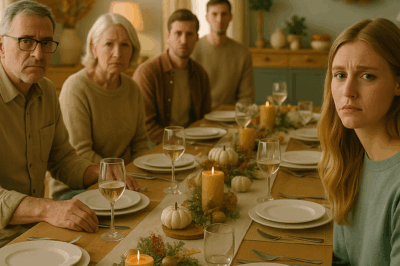

“Useless girl, you were never the bright one.”

My father didn’t shout the line so much as place it carefully on the table like an expert setting a chess piece. He delivered it loud enough for the second row of relatives to hear, soft enough to pretend later he hadn’t meant it that way. The room reacted the way my family always did to his corrections: forks paused midair, wine glasses hovered above napkins, and no one looked at me directly. They looked at my mother’s mouth to see which way the wind would blow.

“Bob,” my mother murmured from behind her hostess smile, a syllable that could mean stop, go on, or please don’t embarrass me in front of your friends—the trilogy carved into every woman of her generation.

“Is the roast dry?” my Aunt Patricia asked no one, and then to me, voice pitched to land only in our row, “Maybe business isn’t your thing, dear. You were always so good with your little crafts.”

Nathan’s laugh, quick and apologetic, slipped out. Twenty-nine years of certainty sat easy on my brother’s shoulders. He had always been good at being approved of. I had always been good at being useful.

I didn’t cry. I carried the paper plate of sliced carrots to the kitchen and stood at the sink, staring at my reflection in the dark window like a suspect in a one-way mirror. My phone buzzed insistently against the counter—Mia’s name bright on the screen.

Did you tell them about the investor meeting?

I typed, Not yet. Timing’s not right, which was our shorthand for no one asked, and I ran out of oxygen trying to make it matter last time. I watched the three dots of her response hesitate, disappear, then return.

Thursday is real. Westlake Ventures confirmed. Olivia—this is the one.

I looked back toward the dining room at the profile of my father’s head, the architecture of a man who had planned one narrow hallway for me and all my life’s furniture had been in the wrong shape. He was saying something to the neighbors now about Nathan’s latest contract—a state government deal that landed him on a podium in a gray suit applauding a bipartisan ribbon. He used words like solid and real, and it didn’t take much imagination to hear the opposite category where my work lived.

I rinsed the plate and breathed until my chest had enough room to sit down again.

The office smelled like hot dust and ambition. Our leased floor in a renovated warehouse had exposed brick, sunlight with opinions, and acoustics that let every keystroke feel like a promise. We named the company NeuroSync after the first few months when it felt like Mia and I were sharing a brain.

“Is that a certificate?” Mia asked, sliding a coffee toward me as I dropped my bag and the award on my desk.

“Participation trophy,” I said lightly. “For the insecure.”

“Family night?”

“Classic,” I said. “Nathan was visible. I was… ambient.”

She made a face that said she wanted to hug me and burn things down. She’d known me long enough not to do either. “Westlake’s deck is where?”

“Version six in the shared folder. Version seven only exists in my head.”

She grinned. “Get it out. Gregory Westlake is not patient and neither are I-beam VC men in white sneakers.”

We had spent three years turning napkin sketches into code, code into pilot projects, pilots into paying clients. Predictive analytics sounded like magic to anyone who didn’t live under its hood; the truth is it’s pattern, pattern, pattern—and one willingness to measure what other people call intangible. Where Horizon Data—the competitor that didn’t hire me four years ago because I “presented as more people-oriented than technical”—pummeled history until it gave them a forecast, we let the present inside. Emotional response signals captured by permission-based interfaces, real-time context ingestion, a model trained to listen for the infinitesimal shifts in behavior that precede a decision. If Horizon could tell you why a customer bought hiking boots last summer, we could tell you that same customer would stop considering your competitor in exactly three days if you changed the color of the checkout button and sent a message with one specific sentence in it. Not magic. Persistence.

Thursday came quickly the way all truly consequential days do—you blink and you’re in the first half-minute of them. Westlake Ventures’ conference room was overcooled and glassy, a surgical theater for money. Gregory Westlake wore a navy jacket like a uniform and sneakers like permission to pretend he hadn’t become the thing he’d sworn to disrupt. He shook our hands and gestured to the head of the table like either of us had any interest in peacocking there.

Mia clicked to the first slide. She and I had practiced the handoffs until it sounded like a duet.

“Historical comp sets adjust for context,” Gregory interrupted fifteen minutes in, the way men do when you’ve reached the part of your expertise where theirs could no longer take them without asking for help. He didn’t know that we had built “context first” and trained the model to punish itself for overfitting. He didn’t know that we had slept four hours in forty-eight last week because we broke something on purpose to see how fast we could fix it at scale. He didn’t know how often we had been told to “maybe look into a lifestyle brand or teaching.” He would soon.

“Historical comp sets adjust for context,” I agreed, and then I made him say out loud what they can’t do. The performing of that admission is half the work of an investor meeting.

Two hours later we were in the marble lobby holding paper coffee cups that weren’t coffee because you can’t drink anything after you talk for that long and still expect your throat to behave. Westlake’s associate was effusive and efficient; the term sheet we’d expected next month arrived that day. Lead round. Ninety. Million. Dollars. Mia squeezed my hand hard enough to mark it. “Olivia,” she said, and then nothing, because we both had the sense that naming things too early makes them skittish.

The next morning I woke up with five voicemails, twelve texts, one email from our decade-younger intern’s mother congratulating us (high school gossip chain?), and a single notification that made my stomach drop: Forbes: Disruptor Alert—NeuroSync Raises $90M; CEO Olivia Reed Is the Youngest Woman in Predictive Analytics to Lead a Round This Size. The photo wasn’t a photo, it was me in a brand-new suit that still felt like a decision. The words were true even if I had wanted to control the timing. The PR firm had pushed faster to catch a tech conference wave. The Wall Street Journal picked it up. Business Insider ran an infographic. My mother texted me an hour later to remind me about Saturday: Don’t forget Dad’s retirement party. Bring those cookies people love 🙂

I stared at the jaunty parenthesis smile until my phone blurred.

“Tell them first,” Mia said from my doorway.

“You heard?”

“I keep my own notification settings,” she said, leaning on the frame, which I had told her not to because I loved it and it was old. “Tell them before someone else does.”

I called. My father answered on the second ring—he always did when he wanted to manage a thing. “Yes?”

“I wanted to tell you before you saw it,” I said. “Westlake Ventures—”

“We saw,” he said. “Your mother showed me the little article.”

“Forbes. And The Wall Street Journal.”

He made a sound that could have been a laugh or a cough. “Those business pages will write about anything these days. We’ll see how long this bubble of yours lasts.”

“Three years of revenue isn’t a bubble,” I said, and then because I couldn’t help it, “No congratulations?”

“Why would I congratulate you for a PR stunt? Your brother just secured a million-dollar government contract,” he said, which was his version of we’ll talk about you later why do you always make things about you. “We’ll see you Saturday,” he added, and then, as if the real work of the call was still ahead, “Don’t be late.”

There are entrances we choose and entrances that arrive because a thousand other entrances were repetitions of the wrong door. Saturday was partly both. I parked at the end of the street and took a moment in the car to make a private promise: I will not be small to win a game where smallness is the prize. Then I stepped out into the early evening in a cream suit that fit like a yes and a blouse the color of lake-in-July, and I watched my cousin’s jaw drop like an apple.

There are entrances we choose and entrances that arrive because a thousand other entrances were repetitions of the wrong door. Saturday was partly both. I parked at the end of the street and took a moment in the car to make a private promise: I will not be small to win a game where smallness is the prize. Then I stepped out into the early evening in a cream suit that fit like a yes and a blouse the color of lake-in-July, and I watched my cousin’s jaw drop like an apple.

“Olivia?” he said.

“Mind parking it for me?” I held out my keys. “The driveway is crowded.”

He took them and didn’t look at the car again. He looked at me the way people look at someone they have rehearsed, then meet for the first time.

My mother met me in the foyer and looked exactly like a person trying to remember whether she had ever told anyone she didn’t have a second daughter. “You look… different,” she said, which is what people say when all the adjectives they’ve been saving don’t apply anymore.

“I feel different,” I said.

My father didn’t turn when I approached the grill; he spoke to a row of bratwursts like they might offer him counsel. “You’re late,” he said.

“I’m right on time,” I said, holding out a gift box. “Happy retirement.”

He accepted it without opening it and nodded toward the yard. “Your brother’s table is over there,” he said, which I think might be the only sentence my father learned in the hospital when I was born.

Nathan’s wife stood when she saw me. Jennifer was always kind in the way women learn to be kind to themselves first. “We read,” she said, clutching my arm. “It’s incredible. Why didn’t you tell us you were building an empire?”

“I did,” I said. “Many times.”

Nathan laughed, fragile. “You know how it gets,” he said in the voice of a man who has always been the thing that gets the time because people will enjoy it more. “Tell me everything.”

I told him the version of everything you can tell at a picnic table with potato salad between you: we coded, we failed, we tried again; Westlake listened; the model worked better than they expected; the valuation is a number that proves something without proving anything. I spared him the nights I sat on the floor of the office and ate pretzels because we hadn’t paid ourselves in two months and the day I had to tell our first intern we’re letting you go because we cannot carry your beautiful energy through a dry spell. That was my story and we were at a retirement party for a man who measured stories in bullet points on a resumé.

People circled. A retired VP clapped me on the shoulder like I had won the right to be interesting. A neighbor who had misnamed me Olivia Catherine for twenty years asked me to explain what “AI” means to him, and I did, because old men at barbecues ask to be explained to and sometimes they need it and sometimes they need to feel like they deserve it.

At seven, my father hit a glass with a fork and smiled with the practiced ease of a man who has been clapping for himself since his high school coach taught him how. He told his story in a way that made all the danger feel like plot points and then he turned to his children. “Nathan,” he said, “who is continuing the family tradition of excellence,” and there were whistles and he basked in them. “And Olivia,” he added, adjusting his weight as if the sentence itself asked him to stan d on a different kind of floor, “who has apparently been quietly building something none of us fully understood.”

“Apparently,” I echoed so soft only Mia, who had come as my date with a blazer and a grin, cracked a smile.

“I always said she was the emotional one,” he said, and people laughed because laughing is easier than not laughing, “but it seems I may have underestimated how far that emotional intelligence could take her.” There was a thin thread of grace inside the sentence, which I took gently and put in my pocket like a grocery list that might still be useful.

His friends turned to me when the Wall Street Journal notification popped on his friend’s phone. The group chat they had titled “The Boys” rung with a photo of my face under a headline about Youngest Female CEO on WSJ’s Weekend Cover. I hadn’t known the Journal was planning a Sunday print piece, but there it was: my face, my company, my name beside the masthead that had sat on my father’s breakfast table my entire childhood. Mr. Linden—the neighbor who runs on Sundays because he likes to see how something can keep rhythm—held his phone so everyone could see. Someone whistled. Someone else said holy— and stopped. My father watched their faces watching me. Speed at which any room reshapes itself to hold changing power: instantaneous.

Later, when the mosquitoes rose and people put on the sweaters they pretend not to own, my father found me by the side fence where he used to smoke and pretend it was thinking. He had opened the box. The watch was on his wrist, the engraved to new beginnings pressed against the thin skin there.

“You knew the Journal would hit today?” he said.

“No,” I said. “We told them next week. PR has its own agenda.”

He looked at the face in the photo and the face in front of him as if to see whether one of them had been edited. “I used to think success was…” he trailed off, searching the backyard for a sentence. “That thing Nathan does. I didn’t know the other thing you were doing counted.”

“I didn’t ask you to count it,” I said. I realized it was the first time I had said a thing like that without an apology attached. The muscles you build when you stop qualifying yourself are surprising.

He nodded. “Wall Street Journal,” he murmured, like the words might order a new world around his mouth. “The guys at the club will—” he stopped, looked at me, and reset. “I’m proud of you,” he said, which is the sentence men keep for the years they didn’t say it and then hope it covers a lot.

“You’re proud of yourself for knowing me,” I thought, but didn’t say. Aloud I offered him the truest thing I could produce while my heartbeat slowed: “Thank you.”

When I left, he shook my hand like a colleague and my mother hugged me like a woman who had Googled how.

Part Two

It’s one thing to be featured on a screen; it’s another entirely to watch a person turn a newspaper around so that you can help him read it. Sunday morning, I drove past the country club and saw a cluster of men holding the Wall Street Journal. They do this when one of their own makes it—a golfer on page B6, a grandson at Yale above the fold. Mr. Linden caught my eye as if I were a neighbor and also an answer to a question he’d been asking for thirty years. He lifted the paper in salute. “Well, well,” he mouthed. Behind him, my father held his own copy like a passport.

He didn’t call. My mother did, because someone had to say something. “Your father’s friends brought the papers,” she said. “They all wanted him to sign your picture.” She laughed, and it might have been real. “He didn’t, of course. He told them he can barely write his own name legibly.”

“We built a company,” I said softly, because at the end of every headline is a staff of people who rolled their chairs closer to a problem with you.

“You worked very hard,” she said in her softest voice, the one she saves for funerals and balconies. “You always have.”

Our new headquarters opened in October. In the months between the dining room applause and the ribbon, we negotiated a lease with floor-to-ceiling windows and carved out space for a nap room that our board didn’t understand; we hired three brilliant engineers Horizon passed on because they were mothers who needed flexible hours; we shipped two releases during a week when the servers ran hot like tea kettles.

When my father walked into the lobby of the building with NeuroSync spelled in frost on the glass, he glanced instinctively up—engineer reflex. He checked load-bearing beams before he said hello. In the elevator he asked about HVAC because he has to ask about things he can name. When the doors opened on our floor, the light made a noise.

“Where are the desks?” he asked awkwardly, looking at the long tables where we had decided on no walls but noise-canceling headsets optional.

“We collaborate,” I said.

He made a harrumph sound that could mean hippie nonsense or interesting or I’m fifty-seven and everything looks like a WeWork now. Then he saw the wall of patents—my name on three; Mia’s on five; our team on many. I watched his eyes—trained for years to scan blueprints—track two lines: what we had made and what he had said I could not.

“Impressive,” he said. He did not say I was wrong. He did not have to.

The ribbon cutting was simultaneous code deploy and ceremonial cliché. We laughed; we sipped; someone spilled something and cleaned it up without making a values statement about it. The mayor sent a staffer with a proclamation that made a sentence like your success is our city’s success feel all at once ironic and sincerely useful. Nathan came and asked a thousand questions like a man who now remembered how to be a brother. My father wore the watch I gave him, which meant he had opened it in private and put it on and decided it could keep time without telling him who he had been.

There is a sentence you keep for people who doubted you. It is not I told you so. It is I’m busy. He asked if we wanted to grab lunch afterward, and I said, “I have a 1 p.m.” It did not feel like punishment; it felt like truth. He nodded and said, “Another time.”

Then the call came from Horizon Data. It arrived a month after the move, on a Wednesday that felt like a stack of Post-its—small items that can bury you if you let them. Mia put it on speaker and rolled her chair into my doorway. “This is James Carver, CEO of Horizon Data,” a voice said, dipped in apology before it got to the olive branch. “We’d like to discuss a partnership.”

Horizon was the company that sent the email four years ago suggesting I look into product management because “you have a great sense for people,” which at the time I translated as we don’t hire women to write architectures. I kept the rejection printed on the inside of a notebook because I am a walking cliché of spite turned fuel.

“What kind of partnership?” Mia asked, brutally pleasant.

“A data sharing initiative,” he said. “We move history; you move feeling. Between us, we could own everything.”

The phrase sat in the room like a snake you can recognize from forty feet—beautiful and poisonous. We scheduled a meeting, partly to see if we could grow something and partly because you should know the neighbor who has been planting invasive species near your fence.

They came in suits, which is not a sin but is a choice, and shook the hands of the people whose resumes they had scanned for things they considered real: Stanford, MIT, The University of People Who Hire Their Friends. They brought a deck; we brought a whiteboard. They talked about synergy as if it were a recipe and not a delicate negotiation between cultures. Mia asked three pointed questions about governance; they deflected twice. I asked one simple question about how they talk internally about the line between prediction and manipulation; the room got quiet in that way that says we don’t ask our theologians into the office on Wednesdays.

We didn’t say yes. We did something better: we told our team we would decide together. Half of them would have loved the access; half of them wanted to watch Horizon catch a cold in the rain. In the middle were the people who wanted us to write a manifesto that would allow them to sleep and ship code.

“Your father’s friends will say you’re foolish,” Mia said as we walked back from the conference room and the last whiff of cologne left with the horizon men. “They will use words like strategic and prudent and too emotional if you decline. I will steal their forks.”

I laughed, and then we wrote a document we called The Porchlight Principle. It states plainly that you don’t model people into puppets and call it progress. That you don’t call coercion conversion. That we will never build for a client whose main KPI is making customers ignore their better judgment. We emailed it to the board and posted a version on the site. The email from my father came the next day. It had four words: Proud of this, Liv.

There is a specific kind of relief in knowing the person who once called you useless will tell his friends at breakfast that you have a principle and not just a product.

My mother started volunteering. This would not make the local news, but it should. Women who have been told their worth is performance often find the first honest ground under their feet picking up things other people drop. She answered phones at a food pantry and then moved chairs and then, one day, apologized to a woman about the way she had once told her story. She told me this in a text that read like someone learning how to use punctuation: i said sorry. i meant it. it didn’t kill me. If you understand matrilineal trauma, you’ll understand why I sat on the bathroom floor and cried.

We invited my parents to dinner quietly, on a Tuesday, the kind of dinner that has no narrative attached so nothing to ruin. My father brought tulips again because now it had become a thing; my mother brought green beans with almond slivers because she refuses to stop believing certain things impress people. My grandmother came because she cannot abide weed growth.

At the table, my father asked about a thing we were building and didn’t correct the answer. My mother asked if she could help chop and didn’t rearrange the knives and we all marveled quietly at how people can sometimes take off their shows and walk barefoot.

In the middle of the meal, when stew had softened the part of everyone that uses armor, my mother cleared her throat. “I told Aunt Patricia I lied about you,” she said. “I told the book club why. I told them I was wrong and that you are not dramatic—you are precise, and I was the only one who couldn’t handle it.” She looked at her hands. “I told your grandmother I was sorry.”

“Sit down,” my grandmother said, standing at the sink with a dishtowel like a crown. “You’ll faint.”

We laughed and then we didn’t, because we were watching a person we have known for sixty years become someone else right in front of us. If this is not religion, I don’t know what is.

The Wall Street Journal article found its permanent home in a frame I didn’t buy. My father brought it—crisp matting, simple black border, the competence of a man who knows how to hang things on walls. “For your office,” he said, and then faltered like he wanted permission to enter a room he had always assumed he built. “If you want.”

I took it into the office early, before the team arrived. I hung it in the hallway by the nap room and the library no one uses because we never finish the book club book but we need the idea of it to feel whole. I stood back and looked at my face beneath the masthead that had once indented the wood of our kitchen table. It looked like me. It didn’t look like me seeking anything in anyone else’s eyes.

“Is that… you?” our intern Sam asked, arriving with a skateboard under his arm and morning enthusiasm.

“Only on paper,” I said.

“Cool,” he said, because he is twenty and does not yet know that paper can stop an argument at a family table that no one thought could be fixed.

Nathan called one night and asked if he could bring over the contract he had bragged about six months ago. He wanted me to look at a clause that felt like a trap. He brought it and two beers and recited what he’d learned: that it’s one thing to get approved by older men with golf tans and another to keep your compass when everyone in the room says “just be reasonable.” We sat on my necessary porch and marked it up and he thanked me and then didn’t take my advice about everything, which is exactly how adult siblings show respect.

“Hey,” he said before he left, hand on the railing our father had once stained, “do you keep the rejection letter from Horizon?”

“Yes,” I said. “Why?”

“Because I want to keep one,” he said. “The one from Dad I wrote in my head.”

I put my hand on his shoulder and squeezed in the language we learned first.

The second Thanksgiving was quiet. My parents arrived on time. My mother kept to the list both literally and metaphorically. My father carved silently and asked where the knives belonged. My grandmother told the story about how a grocery store clerk once asked her if she was lost and she said yes, in 1952—have you seen me? She made us laugh harder than we would have if we had been pretending to like something. We each went around and said what we were grateful for but no one made us say it and the answers were unperformative: the way the light hit the porch at eight in August; the good doctor; the bad day that ended; the fact that the dog doesn’t run away anymore.

After pie, my father stood to go and then stopped. He put his palm on the table I made. “You built this,” he said again, and this time I understood that he meant more than the furniture. “It’s sturdy.”

“It is,” I said.

He nodded. “You were the bright one,” he said. The words fell without drama. He didn’t ask me to place them anywhere but where I wanted. I did not cry. I did put them in the same pocket as the thin thread of grace from months ago. Threads can be braided into something strong if you choose, and if you’re careful not to let them be tied to things you don’t want to pull.

People ask what the moral is as if I learned a lesson and came home to teach it over tea. The truth is simpler and more expensive: I stopped going to tables where I was asked to bring a meal and not my hunger. I wrote rules for my house and stayed when the people I love chose to follow them. I built a company around a porchlight I would want to walk toward if I were lost. And when the men with papers in their hands said my name, I didn’t spend it all on a single night.

My father’s friends still meet at the club on Sundays with the Wall Street Journal. Sometimes there’s a golfer or a donation on the front page. Sometimes there’s nothing anyone they know cares about. But there was one week where there was a familiar face on the cover and a man held up a paper and said, “Bob, isn’t that your daughter?” And for once, the name that came out of his mouth afterward wasn’t the one we all expected.

This is not a story about revenge. It is not even a story about validation. It’s about the long, ordinary work of reintroducing yourself to people who raised you to be someone else and to yourself as someone you always were. It’s about the quiet privileges of control: when to pick up the phone, when to let it ring; when to hang a frame and when to leave the wall blank; when to accept an apology and when to enforce a boundary you wrote with your own tools.

If you ever want a blueprint, I can lend you mine. It starts with build the table. It continues with decide the seating. It ends—no, it doesn’t end—with eat.

END!

News

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… CH2

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… Part One The emergency room’s…

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead. CH2

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead Part…

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My ‘Affairs’ At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… CH2

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… Part One The first…

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

End of content

No more pages to load