My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General.

Part One

My name is Major General Laura Whitaker, United States Marine Corps. And on the day my father married his second wife in front of a hundred people at the American Legion Hall in Fredericksburg, Virginia, I heard him point at me and say, “She’s nothing but a bastard.”

I wish I could tell you that after fifty-four years of living in this uniform and carrying two stars on my collar, those words rolled right off me. They didn’t. They landed sharp and they stayed.

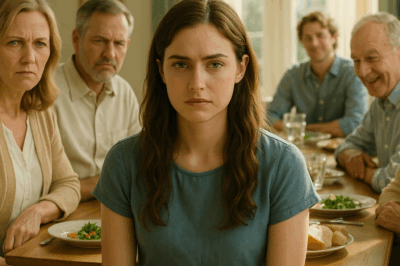

I stood there with a paper cup of coffee that tasted like burnt grounds and Styrofoam. Folded chairs scraped over the floor. Plastic tablecloths shone under fluorescent lights. The DJ was spinning Conway Twitty and the crowd was loose from cheap wine and open-bar Budweisers. Then Dad raised his glass for a toast. He didn’t lift me up in it. He shoved me down.

You could feel the room go quiet. Forks stopped against paper plates. Aunt June gasped and hissed, “Hal, for God’s sake.” Someone chuckled, thinking maybe it was a joke, but it wasn’t. He meant it. He leaned into it. He said it like a man “setting the record straight.”

He puffed out his chest and draped an arm around Ashley, the daughter of his new wife, Denise. She was twenty-six, hair sprayed high, pink dress too tight for the occasion, and a little smirk on her lips.

“This,” Dad said, “this is my real daughter. This is the one who carries my name right.”

I didn’t argue. I didn’t raise my voice. The Corps taught me discipline, but I’d been practicing it long before I signed enlistment papers back in Lubbock, Texas. I set my coffee down and told the bartender—a kid in a bow-tie vest—“Water’s fine. Thanks.” Then I stepped outside.

The parking lot radiated late-summer heat. Cicadas sawed away in the pin oaks. The sun was sinking behind the line of pickups and minivans. A couple of old vets leaned near the door passing a cigarette back and forth. They looked at me, then looked away. Folks never know what to do in moments like that.

Inside, laughter climbed back up like a drunk from a fall. The DJ pushed the volume. I could picture Dad dancing stiff-legged with Denise, Ashley soaking up compliments, telling anyone who’d listen she was a Marine too, stationed at Quantico. She wasn’t lying. She just didn’t tell them the rest—admin, not line; her name crossed my desk last week on a report about falsified travel receipts. But that wasn’t for now.

Right then all I could hear were Dad’s words, echoing louder than the cicadas. Bastard.

I am a woman who buried friends in Arlington. I am a woman who stood watch through sandstorms, who wrote letters to mothers when their sons didn’t come home. And yet, in that hall in front of neighbors and cousins and church ladies, my father took every ounce of dignity I had earned and tried to reduce it to the circumstance of my birth.

Humiliation isn’t just the words. It’s the way they hang in the air. The way eyes avoid yours. The way everyone decides whether to clap or stay quiet. That silence weighs more than the insult.

I thought about leaving—getting on I-95, driving back to Stafford, putting this night behind me. I thought about the garment bag still in the trunk from a ceremony that morning at Quantico: blue dress, polished shoes, ribbons I’ve never bragged about, two silver stars earned the slow way. I thought about Mom—long gone now—who used to tell me, “Laura, you don’t have to fight every fight. But the fights you do pick, fight them clean.”

So I stayed in that parking lot longer than I should have, letting cicadas fill the silence Dad left in me. I decided that when I walked back in, I wasn’t going to fight dirty. I wasn’t going to raise my voice or swing at the man who gave me half my blood. I was going to stand as who I was, nothing more and nothing less.

I didn’t sleep much that night. The motel room smelled of bleach and old smoke. The mattress was stiff; the air conditioner rattled like a loose hubcap. Every time I closed my eyes I heard it again: She’s nothing but a bastard.

You’d think a general would be tougher, and in most ways I am. But the small-town words from your own blood can cut deeper than any battle.

The ceiling texture blurred into memory: Leach, Texas, 1970s. A duplex that rattled in the wind. A swamp cooler that barely kept the kitchen livable in July. Mom—Maggie—came home from double shifts at the diner smelling of fry grease and coffee. She’d kick off her shoes at the door and rub the small of her back with flour-dusted fingers. She was small, but she had a spine I’ve never seen bested.

Dad wasn’t around much. He had his HVAC jobs, or said he did. Sometimes he’d show up in a Ford pickup. Sometimes he’d disappear for weeks. When he came, he had a knack for turning a good day bad with a word or two. He never once showed up for a school play. I learned early that if I wanted something, I’d earn it myself—paper routes in the cold, mowing lawns in August, sweeping barbershop floors for a dollar and a Coke.

At school I kept my head down. I wasn’t the smartest, but I was steady. Teachers noticed. Mrs. Day wrote on a report card: Laura follows through. I didn’t think much of it then. Now it’s the line that hums behind everything I do.

At thirteen, Dad looked at me across chipped linoleum and said, “You’ll never be more than your mama.” He thought it was an insult. I took it as a map.

The summer after high school, while friends packed for Texas Tech or got married too young, I walked into the recruiter’s office on Slide Road. The Marine sergeant behind the desk looked over his mustache and said, “You sure about this, miss?” I was. I signed the papers. Mom cried that night—not because she didn’t want me to go, but because she knew I needed to.

“Laura, you want out? Earn it.”

Paris Island burned off the girl and left the Marine. Sand fleas, heat that soaked your bones, drill instructors who could carve your doubts into shape with a single stare. I didn’t rise fast, but I rose steady. Cleaned rifles until my fingers bled. Learned to navigate by stars when compasses failed. Listened. Followed orders. Then learned how to give them.

I built a life on that rhythm: Camp Lejeune mud and Okinawa humidity, convoy manifests and casualty letters, quiet office work that saves lives and noisy field work that tests them. Promotions came slow, then all at once—colonel, brigadier, major general. I never chased stars. I chased being useful. The only thing I ever bragged about was the Marines I got home.

Which is to say: by the time I stood in that Legion Hall with a cheap coffee, I had a ledger full of quiet proofs. Dad’s sentence tried to audit them out of existence.

The invitation to his wedding came in a cream envelope with my name spelled Whitaker instead of Whitaker. That, too, was Dad all over: the broad strokes right, the details dismissed. I wasn’t going to go until Aunt June called. June is the reason more girls survive families like ours. She’s the one who slipped me lunch money senior year and drove me to the bus station when I left Texas. “Honey,” she said, “even if it’s just for five minutes to hug me, show up.” So I did, wearing a plain navy dress because Dad’s day didn’t need my shine.

You know the rest. The speech. The silence. The parking lot.

I called an old friend from Okinawa, retired Major General Ortiz, because sometimes even generals need someone to say the obvious. “You earned that uniform,” he said. “Every stitch. Wearing it isn’t petty. It’s the truth. Don’t say much. Don’t raise your voice. Just be who you are.”

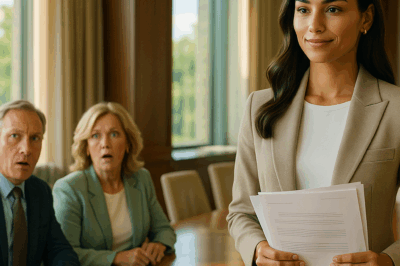

I unzipped the garment bag in the trunk. Wool and starch smell brought back a thousand mornings. Piece by piece I put it on—shirt crisp, collar snug, ribbons in their rows, stars bright. In the rearview mirror a woman looked back at me who had built a life brick by brick, no shortcuts, and kept receipts.

When I pushed open the hall door, the blast of air-conditioning carried out every conversation. The music cut off as if the DJ had yanked the cord. He didn’t need to. My heels announced me on the linoleum. I didn’t make a speech. I didn’t scold. I lifted my glass of water and said, “I came tonight to wish my father a good life. I didn’t come for speeches and I didn’t come for insults. I am who I am, and I worked for it.”

Then I turned to Ashley—poor kid, too much blush, too much wine and suddenly too much truth—and she stared at me like a mirror that showed her the future.

“Oh my God,” she whispered, voice cracking into the quiet. “She is my general.”

Someone clapped. Aunt June first, of course. Then the old vets in the back stood stiff and saluted. People who’d been quiet because they didn’t know which way the wind was blowing remembered where north was.

Dad didn’t clap. He didn’t have to. He’d done enough for one night.

I walked out before the song started again. I wasn’t there to teach anyone a lesson. Life would do that on its own.

Part Two

Quantico is a place that teaches you repetition in the service of meaning. You lace your boots the same way, you check your gear the same way, you say the same words to young officers who think they invented both ambition and fear, and if you’re lucky, five or ten years later they send you a note that says, “Ma’am, you were right.”

I returned to that rhythm. Inspections. Staff meetings. Casualty briefings that never get easier. Paperwork high enough to hide behind. Ashley’s memo about falsified travel crossed my desk again. I treated it like I would any Marine’s: counseling, restitution, a mark that could become a scar or a story depending on what she did next. She came into my office sober, scared, and open. I told her the truth. “You can fix this if you stop lying. Own it, pay it back, clean it up.” She nodded and did.

The wedding story filtered through the base the way stories do—through smoke pits and chow lines, Far Side comics tacked to corkboards and late-night barracks conversations. Marines asked me with their eyes if I was all right; I answered with a nod that meant back to work.

Two months later I presided over a change of command. Flags snapping in a blue Virginia sky have a way of mending things you didn’t know were frayed. Families filled folding chairs, beaming and blinking both. The band played a march that makes your spine stand an inch taller.

Afterward, a line of hands to shake. A dozen “Thank you for your leadership, ma’am.” And then—unexpected as a summer shower—Dad. Sports coat a size too big, tie crooked, hair thinner than memory. No Denise, no entourage, just him.

He stuck out his hand. “My daughter,” he said in a voice he had to clear once to steady. “General Laura Whitaker.”

Not bastard. Not nothing. Daughter. He said it loud enough that the lieutenant behind him heard and the gunnery sergeant beside him translated it into a respectful nod. I shook his hand and said, “Thank you.” It wasn’t absolution. It was enough.

We didn’t fall into each other’s arms. We didn’t do a Hallmark version of complicated. We walked to the parking lot and he told me about a creaky knee and I told him about a Marine from Iowa who could field-strip a radio in the dark. It was small talk carried by big effort. Sometimes that’s all two people can manage at the start of a ceasefire.

He sent a voicemail later I didn’t play for a week. “Laura,” he said, voice unsteady, “I went too far. Shouldn’t have said it. Don’t know how to fix it.” You can’t fix it, I thought. You can only say the right true sentence loud enough in public that the wrong one begins to fade. He’d done that. That, I decided, would be the boundary between us: the truth he said aloud would be the bridge he was allowed to cross.

Time did the thing time does when you let it. It sanded the sharpest edges and left the line still visible. I worked. Ashley worked. Denise posted photos from wine tastings. Aunt June texted recipes and gossip. Dad wore his sports coat correctly sized at the next base ceremony and never again introduced me as anything but my rank and name. He even stopped saying “bastard” about people whose politics he didn’t like. Progress is sometimes a single word removed.

A year later I requested reassignment from field command to strategic training. No scandal. No push. Just a woman who had carried the weight long enough deciding it was time to shape hands to carry it after her. I hung my stars on a nail by the door when I got home and sat on the floor in front of the couch counting the reasons: twenty-one years of young Marines’ faces I could name, eight folded flags, three surgeries I could put off no longer, and a heart that needed to beat to something quieter than deployment orders.

The new office had a window that looked out at pines instead of parking lots. I wrote the curriculum I’d wished someone had written for me—about listening as a mission asset, about the silence between words being as important as the words, about how you can lead without shouting and correct without humiliating. We called it the Listening Lab. The sign on the door just said Room 3A, but the Marines called it Whitaker’s Well because you could come in dry and leave with something worth carrying.

On a Thursday I found a small metal plate taped to the door with green painter’s tape while Facilities waited on screws. It read, THE GHOST WALKER ROOM. Some wit had stolen the nickname from intel folks and decided my little lab deserved it. I left it up. Not because I am a ghost. Because sometimes what you teach best are the things you learned in the dark.

Ashley stopped by that afternoon with a stack of receipts and a look I recognize as penance mixed with pride. “All paid back,” she said, laying the stack like an offering. She cleared her throat. “General, I… thank you for not ending me.”

“You ended it yourself,” I said. “I just gave you the form.”

She laughed, surprised, and left with a straighter spine. A week later she sent a note that said she’d been accepted to an officer program. I wrote follows through on the bottom of her file and smiled at Mrs. Day somewhere in the past who had written the same on mine.

Dad came to one more ceremony. He stood three rows back this time, Denise on his arm, hat in his hands. He didn’t say much afterward. He didn’t need to. He had chosen the right sentence and stuck to it. I stood in the late light after everyone left, listening to the flag halyards clink against metal in the breeze, and thought about all the words we hold and all the ones we let go.

Here’s what I believe now, and it’s simple enough to fit in the space between a toast and a pause:

You are not the worst thing anyone ever said about you. You are the ledger of every quiet morning you showed up when it would have been easier not to. You are the steady works and the clean fights. You are the salutes you’ve given and the ones you’ve earned.

If your reckoning comes, let it come clean. Put on whatever uniform your life has given you—actual wool and ribbon or figurative grit and grace—and stand in the door. Don’t shout. Don’t swing. Let the room see you.

Sometimes the room needs it. Sometimes the father does. And sometimes the daughter, God help her, needs to hear somebody younger say, “She is my general,” so she can finally whisper back to herself, I always was.

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load