My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped, “She’s My Boss”…

Part One

The screen of my phone trembled in my hand. My father’s words hung in the static between us, each one chosen, polished, and launched with the flat certainty of a foregone conclusion.

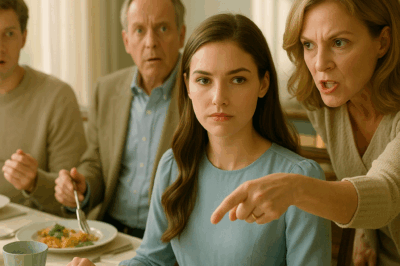

“Jessica’s bringing her boyfriend home for your mother’s birthday,” he said. “He’s someone important. Speaks well. Carries himself properly.” A deliberate pause. “And your job… well, it isn’t very comfortable to talk about. It’s best if you don’t come.”

Outside the glass of my office, Seattle was exhaling dusk—the mountain a faint graphite cutout, the water taking back light and giving back steel. Inside, the remark landed on the mahogany my assistant had insisted I buy when we closed Series C, and for the first time since we’d moved into the top floor five years ago, my desk suddenly felt like a prop.

“What are you saying?” I asked. My voice came out low enough to surprise even me. A dangerous calm wrapped in something older.

“You coming home would just embarrass the whole family,” he replied, the tone flattening as if by removing pitch he could remove culpability. “If you still insist on coming, don’t call me your father.”

The line disconnected with a soft click that somehow echoed louder than any slam. For a long moment I stared at the phone as if it were a mouth still open around a bite of something too hot.

Then my banking app flashed to life. Transfer Complete. The automatic monthly payment of $397.68 for my parents’ utilities—power, water, internet—had just processed. Little gray dots on a timeline: twenty-three months of loyalty that didn’t even have the grace to be reciprocated with pretend gratitude.

I’m Olivia Walker—thirty years old and the silent co-founder of Pacific Teritech, a sustainable energy company that began in a rented garage that smelled like solder and ambition. These are two of the truest things I know about families: they can feed you long after you can buy your own groceries, and they can starve you while eating from your hand.

I set the phone down, stood, and looked at the city the way I learned to look at results: from multiple angles. We’d laughed when my co-founder Mark said the best view is rented, not owned. I knew better. Views are earned—like patents, like trust, like the right to name the pain that you have paid for.

The next fifteen minutes happened as if another person had borrowed my hands.

I opened my bank portal, navigated to Recurring Payments. One by one—power, water, internet; click, confirm, password; click, confirm, face ID—I canceled all of them. Not out of vengeance, but out of an instinct older than love: self-preservation. When I pressed the last confirmation, my hand shook. Not from doubt. From the terrifying relief of choosing myself after three decades of choosing them.

My mother texted two weeks later. Just got a notice that the internet bill is due. Can you take care of it? No mention of my father’s ultimatum, no apology, just a flicked invitation to resume an old performance. I stared at the message until the letters blurred, then set the phone down and returned to reviewing the quarter’s solar storage projections. My silence was not a statement. It was simply all I had left to give.

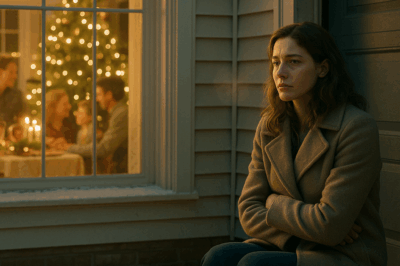

Three weeks after my father disowned me, my mother’s birthday arrived in the calendar like a bruise you forget about until you bump it again. I could see the scene without being there: her favorite roasted chicken, cake from Bramble & Vine with the rosemary-lemon frosting, relatives sticky with wine conversation. My absence would be a tidier story than my presence. It always had been.

At 4:00 p.m., my mother’s name lit my screen. I let it ring until the call died. My father’s call came—declined. Then Jessica’s—declined. The old ache tried to get into my body through my throat, found the door locked, and slid down to sit on my sternum like a drop of mercury.

By 5:12 p.m., the messages began:

From Mom: Olivia, the power has been turned off. The entire house is dark. Please pay the bill.

From Dad: No water. We can’t cook. Handle it now.

From Jessica: Internet’s down. Guests are arriving. Please fix this urgently.

I placed the phone face down and wrapped my hands around my coffee mug, rotating heat into my palms. Outside, rain stitched diagonal lines across the window. Inside, the past thirty years and the last three weeks met in the oldest arithmetic: they were not calling because they missed me. They were calling because there was no one left to carry the weight they’d placed on me and told themselves was love.

By 6:00, my phone buzzed itself toward the edge of the table. Cousins I’d not spoken to in months sent paragraphs. You embarrassed your mother in front of everyone. Your sister was right. People like you shouldn’t show up on happy days. People like you. I read without responding. Not because silence meant surrender, but because I had finally grown tired of explaining the truth to people who always chose the louder voice over the quieter reality.

Then: Aunt Lauren—Video Call. The name made my chest loosen. My mother’s younger sister, who cooked real casseroles and taught me to love library air conditioning in August, who looked directly at me in rooms designed for avoidance.

I answered on the second ring. Her face appeared lit by the yellow kitchen light I knew like my own hallway—the one where I’d hidden in an adult coat watching legs when I was six. Tonight the room behind her looked like a play where everyone forgot their lines. Uncomfortable laughter. Strained forks. The hum of a refrigerator working harder in the dark.

“You’re not going to pay for it, are you, Liv?” she asked. Not accusing. Curious. Soft as a worn sweater.

“You know what he said,” I replied. “He told me if I came I should stop calling him my father.”

She didn’t speak. In the background, chaos flared. My mother’s voice, sharp with tears. “Tell her I’m ashamed. On this day of all days—”

My father, brittle with impatience. “It’s not that serious. It’s just paying a few bills. What kind of daughter gets petty over money?”

An uncle chimed in. “Poor Jessica having to deal with a sister like that.”

Footsteps approached the camera. Jessica’s face cut into frame, highlighted cheekbones and certainty in her chin. Arms folded. “She even picked up the call. Mom’s been crying all day. Does she even care?” She leaned closer. “Seriously. No shame at all.”

I kept my face still. I had long ago learned the difference between wounded and wrecked. I was neither.

A new face appeared at the edge, hesitant, then fully in frame. A man in a dark suit with the posture of someone trying not to offend furniture. He looked at me through the screen the way engineers look at unexpected variables—then drew in a breath.

“Hey, boss,” he said, voice cracking on the second word as if expecting the room to correct him.

For a heartbeat, the kitchen froze. Even in pixels, I could feel the air thicken. Recognition arrived like heat. Hudson—last name Kane—the senior engineer who’d transferred from our southern branch to Seattle three months ago. We had exchanged long emails about battery chemistry, debated error bars, laughed in parenthetical jokes. I had not known he was Jessica’s boyfriend. Of course I hadn’t. My sister had described him as a “consultant,” vague in the way she weaponized ambiguity.

The room erupted in whispers.

“What did he call Olivia?”

“Boss?”

“Do you mean—”

“In case you didn’t know,” Hudson said into the space between past and present, “I work at Pacific Teritech. Ms. Olivia is one of the company’s co-founders.”

The line clattered like dropped cutlery. The camera jostled. Aunt Lauren turned so the phone saw a tableau: my father’s mouth semi-open, my mother’s hand on her chest, my sister’s face going through seven expressions in four seconds. Somebody whispered my name as if I were a rumor that had grown legs.

I lifted my chin half an inch and offered the smallest nod. “Hope your big introduction goes perfectly,” I said to Hudson, and ended the call.

That night I slept through my alarm for the first time in a decade. Not from triumph. From the weight finally sliding off my spine like a coat that had always been too heavy.

In the morning, before the sun pushed itself fully into the sky, an email from Hudson waited at the top of my inbox. I’m sorry. I didn’t know you were Jessica’s sister. I’ve always respected you at the company. He explained—carefully, kindly—that Jessica had described me as “a receptionist who helps with paperwork” and that he’d been embarrassed to realize he’d carried that description into our first handshake. He ended with: I didn’t expect her to be like that. I’ll be ending this relationship. Thank you for not putting me on the spot in front of everyone.

I set my phone on my chest and stared at the ceiling for a long count of ten.

Then I wrote: Hudson—That’s your decision. I don’t expect anyone to perform loyalty for my sake. Think carefully before you do anything permanent. And for the record, I don’t bring family into the workplace.

I hit send, finished my coffee, and took the elevator down into a day that smelled like rain and apology.

By ten, Jessica called. I declined. A text arrived seconds later. I’m sorry. I didn’t think Hudson would change like that. You’re his boss. If you said something, I’m sure he’d listen. Please talk to him. Ask him to come back to me.

I stood at the window with the phone in my hand and practiced the sentence I wish somebody had given me at twenty-three. Then I typed: Hudson didn’t leave because I told him to. He left because how you treat people is finally visible when the lights go out. He left because you’ve spent years mistaking softness of voice for rightness of action. He left because of you, not because of me.

I hit send. She wrote again. I know I messed up. I’ll change. Please believe me. Just this once.

I deleted the message without answering. Not because I didn’t care. Because I had learned that sometimes the distance between two people isn’t covered by an apology. It’s covered by the timing of one.

Two weeks later, HR forwarded me a transfer request from Hudson: lateral move back to our southern branch. I approved it immediately and wrote a one-sentence note to his new lead: He’s good at spotting failure modes in systems and people; let him fix them in that order. He replied with a smile emoji; the world, even in corporate, sometimes cooperates with grace.

The following Friday night, a knock on my apartment door replaced my usual habit of ordering Thai and reading preprints. When I opened it, my parents stood there with small suitcases and faces that looked like sunk costs.

I stepped aside and let them in. I made tea. We sat in a triangle where so many of my childhood dinners had been an oblong.

My father spoke first, an apology made of soft words and heavier air. My mother added that “perhaps” things should not have gone “that far,” that “every family says things,” that “birthdays bring tension.” It was like listening to a weatherman explain the flood that swept away your house: interesting but not helpful.

I listened. I do not interrupt anymore. When my father’s language shifted from regret to rationale, I put my teacup down and let it be loud on the saucer.

“We’re family,” he said, sitting straighter as if posture could re-erect a toppled status. “Family helps each other. We raised you. We sent you to school. Everything you have now, a part of it comes from us.”

A muscle in my jaw made a small decision of its own.

My mother leaned forward, voice softening into the tone she had always used to cushion requests. “If you could maybe send us… about $2,000 a month. Just a little support. It’s not much for someone like you.”

I studied them the way I study data: for trend, for anomaly, for human error. The math of their apology was as clear as the ledger I no longer kept.

“What about Jessica?” I asked. “How much will she be contributing each month?”

They exchanged a look like two people realizing they’d forgotten a vital attachment. My mother recovered first. “Your sister’s job—well, it’s still unstable. And the breakup—she’s not herself. Couldn’t you…?”

“If she agrees to support you with $2,000,” I said, steady, not unkind, “I’ll do the same. No more, no less.”

They stared, waiting for the punchline I had removed from my repertoire.

“Or,” I added, “if you want me to carry the full amount, I’ll need something in writing. A legal agreement confirming that after you both pass, the house will belong to me in full.”

Silence grew itself a spine and stood in the room with us. My father’s face went a color I remembered from childhood: righteous. He pushed hard against the table; tea ran in a tributary. “You’re setting conditions for your parents,” he shouted. “We raised you, fed you, clothed you, for twenty years—now you want to nickel and dime us?”

My heart did not pick up speed. It looked at the scene from a little above and a little outside.

“I think you should leave my house,” I said. Not an order. Not a threat. A boundary.

They left dragging their luggage. The door made the softest sound I had ever heard. A door can be kind if you let it.

At the window, I watched them walk away small and old. I put my hand on the glass and felt exactly what the glass could give me back.

It was not rage. It was a release.

Part Two

Two years is a long time if you’re waiting for a person to change. It is a very short time if you are rebuilding a life that had been structured around earning something you already deserved.

In two years, the company doubled its installed capacity of residential solar storage on the Peninsula. Our new battery prototype survived six abuse tests and one congressional hearing. We hired a cohort of apprentices from a community college feeder program we funded, and half of them showed up on the first day wearing steel-toed boots and shy smiles that looked like possibility.

In two years, I learned a new quiet: the absence of my phone vibrating with requests masquerading as love. The absence of the old puzzle—how to fit myself into the silhouette of the daughter they’d drawn from memory. In two years, I did not receive a birthday message. I did not receive a congratulations when Pacific Teritech made the Forbes list I did not agree with. I did not receive a single “How are you?”

Jessica wrote once, six months after my parents asked for a stipend. Can you put in a word for me at your company? Maybe something in PR. It would really help right now. I replied: We don’t hire family. I hope you find something that fits you. She responded with a GIF of an eye roll. Then nothing.

Hudson thrived at the southern branch. He sent me a Christmas card with a hand-drawn battery wearing a Santa hat and a note that said, Your boss voice is scary in a good way. When he visited headquarters for a design review, he nodded respectfully in the hall, then waited until after-hours to say, “Best decision I ever made, to leave.” I rolled my eyes and told him not to make me his moral.

On the first day of the third year, my doorbell rang. I opened it to find a young woman holding a bouquet of slightly dented peonies and a lunch bag with my last name on it in crooked Sharpie.

“Aunt Olivia?” she asked, the vowels careful as if she had practiced.

“Amy?”

She looked taller, the way kids manage to do in a single summer. Public school had given her a backpack with pins on it and a habit of looking adults in the eye while keeping an escape route in mind. She pushed the bouquet forward. “Mom said I shouldn’t bother you. Grandma said you were probably busy. But I looked up your office hours and your walk score and guessed. If this is weird, I can go.”

“It is weird,” I said. “Come in anyway.”

We ate peanut-butter-and-banana sandwiches at my kitchen counter. She told me about robotics club, about the teacher who had once worked for a three-letter agency and now taught eighth graders how to debug their lives, about the way she misses the pool at the old house but likes the bus because she can sit wherever she wants if she gets on at the first stop. She did not mention the night the lights went out. I did not mention the email about the transfer.

“You really built that company?” she asked, not full of awe, just information-seeking. “Like, from zero?”

“With Mark,” I said. “We maxed out two credit cards we should not have. We ate ramen for a year. We cried with joy the first time a customer sent us cookies.”

“My mom said you were smart,” she said neutrally. “But she said you didn’t believe in family. That you’re… cold.”

I took a breath and spread jam. “I believe in family so much I want it to be true,” I said. “Sometimes the kindest thing you can do for a family is stop letting it hurt you.”

We sat in a silence that was not empty.

“I have something for you,” I said, and pulled a small box from a drawer I had kept closed for two years. Inside: a pearl hair clip I’d bought for her back when I still believed glitter could change how we felt. She picked it up carefully like a component she’d solder later.

“It’s pretty,” she said. “But it looks like it should be worn on someone else’s head.”

“Then wear it when you want to be someone else,” I said. “And when you’re done, take it off and be yourself again.”

She smiled. “Deal.”

We made a standing date: first Saturday of the month, pancakes and a walk with a map she drew herself. We never talked about utilities. We talked about engines and why people lie and how to file for FAFSA. I taught her depreciation. She taught me TikTok. Both came in handy in quarterly reviews.

In the second spring, I got a text from a number I didn’t recognize. This is Rachel—Quinn’s mom. May I call? I sat on the edge of my desk and told Danielle to hold my next meeting. The call lasted seventeen minutes and eighteen seconds. She cried at minute four and then started laughing because she’d never done that on the phone with me before. She told me she had started volunteering at the resource center two days a week. “Do you have any idea,” she said, “how expensive bus passes are? Do you know how far a person can go on seven dollars and how quickly it gets spent on trying?” She said she was sorry for the way she had been complicit in my humiliation. She did not ask me for money. At minute sixteen, she asked me if I could come speak to the girls’ leadership workshop. I said yes. I do not always make it easy, but I like doors that open both ways.

As for my father—he mailed me a letter that began Dear Ms. Walker and ended Sincerely, George. It contained an itemized account of the cost of my upbringing and a handwritten note that said, You have done well—do not forget who helped you. I did not respond. I put it in a box labelled “Records” and felt something old in me sit down with the patience of a person who finally understands that some debts are imaginary, especially the ones designed to keep you paying forever.

Work became the truest place in my life not because it made me rich, but because it made me honest. I started every all-hands with a story about failure. Mark told the one about the prototype that melted on a client’s kitchen counter. Kenneth told the one about over-promising to an investor and waking up with a stomach ulcer. I told the one about paying my parents’ utilities for two years because love had been given to me as a ledger.

One afternoon, a new hire asked in the Q&A, “How do you decide when to stop giving?” I said, “When your gifts buy silence more than they buy growth.” I watched faces shift. I knew which employees were thinking about a younger sibling or a parent with a permanent empty pocket. The next day, HR proposed a financial literacy workshop. I said yes and sat in the front row.

On the third anniversary of my mother’s birthday blackout, a thin envelope arrived. Inside: a photo of the dining table at my parents’ house. I had grown up tracing this table’s wood grain with my finger until it felt like a map. In the photo, it was covered with a plastic tablecloth printed with sunflowers. In the center, a plain cake with “HAPPY BIRTHDAY” spelled in red tube icing and a single candle shaped like a question mark. My mother’s handwriting on the back: We’re getting used to candles. Good thing I like the light. It was the first time in three years I laughed about anything that had happened on that day.

And then came a day when I did something even my closest friends called “impractical” and even I called “maybe grace.”

It had been raining hard, the Seattle kind that insists on itself. I was leaving the resource center after leading a workshop where teenagers with old eyes taught me the difference between need and want. In the lobby, an older man struggled with the umbrella mechanism. He looked like someone who had once told his hands they owed him obedience and now they were taking orders from time.

“Here,” I said, taking it gently and popping the hinge into place. He looked up. It took both of us a second.

“Olivia,” my father said. He said my name like a person tasting a new recipe of a dish he’d always disliked.

The old ache tried to find my muscles. It found a person in the doorway holding the umbrella he needed.

“George,” I said, because he had asked for that once.

We stood together under the shelter while the rain introduced itself again and again to the sidewalk.

“I volunteer here sometimes,” he said, as if embarrassed by the softness of that verb. “They needed someone to fix the old bikes so the kids could get to school. Did you know you can get a whole new life out of a chain if you soak it in kerosene and patience?” He laughed, surprised to find he could.

“I do know that about machines,” I said. “I’m learning it about people.”

He nodded, eyes on the street. Then, very quietly, he said, “I was wrong.” He did not list reasons. He did not wait for absolution. He just placed the words between us like a tool I could choose to pick up or not.

I picked it up. I looked at the teeth, the handle, the way it might fit in my hand.

“Okay,” I said.

We walked out into the rain. I held the umbrella because his hands were busy with a grocery bag full of chain and second chances. At the corner, we paused the way you do when you’re thinking about turning. He went left. I went right. The umbrella had been mine; I left it with him.

That night, I told Aunt Lauren. She sent me a message with exactly three words: It’s a beginning.

I do not know if my family will become the kind of family I dreamed of when I was a little girl at a table tracing maps into wood. I know that I am the kind of woman who will never again ask people to see me through the costume they’ve chosen.

And I know this: one evening a man who disowned me because my job was “not comfortable to talk about” watched his daughter’s boyfriend—standing in his kitchen like a mirror—say, “Hey, boss,” and the world as he had built it lost a screw it could not find again. The chandelier did not fall. It hung at a safe angle and reminded everyone in the room that gravity exists for all of us.

Was I wrong to refuse two thousand dollars a month to aging parents who raised me?

I used to ask myself that at 3:00 a.m., as if the dark were their defense attorney. Now I ask it in the light and hear the whole question.

Was I wrong to refuse to be a wallet they called “love,” a plug they called “daughter,” a silence they called “respect”?

I don’t think so.

Some debts are real: the ones you owe to people who gave you back to yourself when you forgot your name. Some debts are a leash. Know the difference. And on the day you learn it, expect the electricity to flicker. Expect the room to go quiet. Expect to find, when your eyes adjust, a door you didn’t see before—leading to a life where your value is not up for whisper.

END!

News

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My ‘Affairs’ At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… CH2

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… Part One The first…

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own… ch2

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House…

End of content

No more pages to load