My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House and the Lodge

Part One

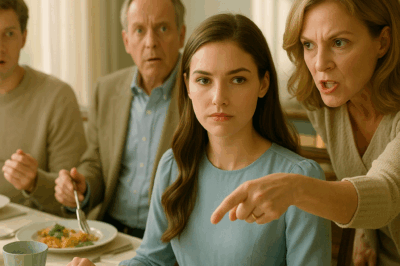

The fork shook in my hand when my mother said, brightly, “Oh good, you’re here, Nora. We went ahead and made up the garage so we wouldn’t have to scramble last minute. There’s a space heater out there, so it’ll be… cozy.”

She said cozy like it was a wine note and not a forecast. Conversation around the table paused just long enough to cut, then resumed in the same forced merriment that follows a clumsy toast. My sister Brianna’s diamond bracelet flickered in the light—the same way she does when she knows there’s an audience. My brother Caleb’s eyes skated away from mine, and he said, to no one, “Weather really turned, huh?”

“Garage?” I asked, because some lines deserve to be underlined.

“You know we’re full up,” my mother trilled. “Brianna and Ethan have the guest room, they flew in from Dallas, they’re exhausted. Caleb’s on the pull-out because of his back, and Aunt Liv is in the office because of her… hip.” She elongated the last word, as if hips demanded reverence.

“I can grab a blanket from the linen closet,” Brianna offered sweetly, performing compassion. “We don’t want you to be cold.”

I looked at the thin smile on my father’s face—the one he wears like a tie when he’s determined to get through dinner without incident. Seventeen Christmas Eves in this house, and I could read these variables like a blueprint: the hung ribbon garland, the good china, the little ways my family telegraphed who belonged where.

My phone buzzed in my back pocket. Fourth message from the board. All-caps URGENT in the subject line. We’d spent six months positioning Northline Capital—my company—into the perfect arc for a quiet acquisition of Hallowell Hospitality, a portfolio that included the Tannenhof Lodge & Spa: the mountain resort my family had rhapsodized about all fall like it was Eden with valet. The deal closed three weeks ago through a subsidiary. The only thing left was a signature on a Monday morning addendum to swap the lodge’s third-party management for our in-house team. Mr. Townsend, my brother-in-law’s boss and tonight’s guest of honor, would be presenting his year-end report to me tomorrow morning without knowing it was me. He had been trying—desperately, embarrassingly—to get me on a call for two days.

“Nora?” My mother’s hand hovered with the gravy boat. “Potatoes?”

“Sure,” I said. My voice came out warm—muscle memory. I passed plates and poured wine and navigated the social choreography I could perform in my sleep.

Caleb asked Mr. Townsend about golf. Brianna launched into a story about a boardroom she’d “crushed” last Tuesday, colliding into the punchline with that practiced self-deprecation rich people use to inhale applause. Dad nodded through it all like a metronome.

I was the only one who heard the humming breath through the vents, the rattling, the telltale sound of the garage heater working twice as hard as it should. It had never warmed that concrete box in thirty winters. It wasn’t going to start tonight.

“Mr. Townsend,” Brianna said, the same note she used in college when she asked professors questions she already knew the answers to, “do you still need help with that… what did you call it? Strategic alignment? I told him I’d pick your brain on the call tomorrow,” she added to the table, as if scheduling with an executive were a social favor. “You have that… flexibility,” she added, blinking at me. “You do, don’t you, Nora?”

Translation: You don’t have a real job. You can take any meeting at any time, because your life sits on the couch in a faded hoodie.

“Tomorrow’s packed,” I said, and took a sip of water. “But I’m sure she’ll be on.”

“She?” Mr. Townsend’s wife asked, genuinely curious.

“Mrs. Hallowell,” Brianna said, then rolled her eyes. “Or whoever. There’s this phantom CEO behind the fund that bought our company last year. Nobody’s met her. Frankly, it feels unprofessional. If you ask me—”

“Nobody asked you,” I said, softly enough that only she reacted. Her fork flicked the edge of her plate.

The rest of the evening was the long familiar theater: coats collected, stories repeated, my mother’s little digs wrapped in evergreen ribbon. When Dad brought out the pfeffernüsse, the first snow began, slow and straight, like a decision being made.

Brianna drew me toward the mudroom like a hostess leading a stranger to the restroom. “We pulled the cot out,” she said, pushing open the door to the garage with two fingers like the cold might try to bite her. “See? Heater’s already on.”

It was offensive: the cot so low you could kick it by accident, the checkered blanket, the IKEA lamp thrumming on its last watt, Dad’s golf bag looming like a witness. They’d moved the plastic shelving unit that held my childhood trophies—debate, JV track—so the sightline from the kitchen would be “clean.”

“Try not to bring any dirt in when you come for breakfast,” Brianna said. “The runner is cream.”

“Got it,” I said, and smiled like a person who didn’t own nine percent of her husband’s company.

The door sighed shut. I stood there and let my eyes adjust. The heater’s red coil looked like a warning. My breath came out in little scrims. I set my duffel on a box labeled CHRISTMAS—MANTLE in my mother’s hand and sat on the cot. It squeaked like a mouse complaining.

Another buzz in my pocket. My COO, Susannah: Townsend emailed again. Begging. Do you want me to give him “10 minutes on Christmas morning” as a present? I pictured him banging against my assistant like a bird against glass and texted back: No. Make him wait until after dinner tomorrow. Move the pre-board to 8 a.m. Send agenda.

Also—Susannah again—the lodge GM asked if the owners want to comp the Anderson brunch. Apparently someone from that party called on the “owner’s connection.” I smiled and typed: Comp two mimosas. Then full price. Add service fee.

Something settled inside me then. Not anger. Not even satisfaction. Just a stillness that let me hear my own pulse. I had been building and building and building—funds, shells, portfolios—for years while playing the family version of myself that made everyone else comfortable: the Former Barista-slash-Adjunct who “never reached her potential.” I had no intention of revealing the gloss of my life tonight. But I had an intention of my own: to stop playing dead.

I texted one more person—the property manager at Halcyon Residential, one of Northline’s quieter holdings.

MARTIN: Are you up?

Always. Problem?

Do we still hold the note on 217 Willow?

Through Lanson Trust. Yes. Why?

Pipe inspection tomorrow at nine. Temperature drop. Owner is liable for any damage incurred from lack of winterizing. Bring paperwork.

There was a beat, then: Copy. Want me there?

Yes. And bring Ada.

Ada—my attorney—drafts boundary lines like poems.

I put my phone on the box and lay down. The cot complained, the heater hummed, the garage gathered around me like a bad habit. I slept the way you sleep when you’ve outgrown a room and don’t know where to put your elbows.

Christmas morning tasted like the Moka pot coffee I’d brought in my duffel because my mother buys the kind of pre-ground that tastes like a shadow of coffee if you apologize to it. I warmed my hands and listened to the house wake up: the kettle on the stove, the rustle of wrapping paper, the early laughter that never includes my name.

I texted Susannah a picture of the garage heater and she sent back the laughing-crying emoji and murder. Then: 8 a.m. agenda sent. GM confirmed. The brunch will be… festive.

At 8:42, I heard tires on the frozen street. The garage door moaned open, the cold made a grab for my ankles, and three figures walked in—the kind of trio that looks like a threat in a movie but in my world just looked like work: Martin in a sensible peacoat; Ada in a scarf the color of warning; and a plumber named Vaughn whose face I recognized from his invoice last February.

“Inspection, ma’am,” Martin said to my mother when she cracked the door from the mudroom, an apron like a truce flag around her waist. “We emailed last week. Cold snap. Frozen pipes are a liability issue.”

“I’m making hollandaise,” my mother said, as if that were a reason to cancel physics. “Can’t this wait?”

Ada stepped forward, her voice gentler than her eyes. “We are obligated to prevent a loss. Owner’s agent. This will only take a moment.”

“Owner?” my mother repeated, because language has power if you’ve never learned to speak it upward. “What owner? We own this house.”

Martin opened a folder. “Lanson Trust holds title. Nine months ago, the property transferred to the trust as part of a restructured note. Monthly payment schedule shows—”

My father appeared behind my mother and tried to make his voice heavier than his bathrobe. “There must be some mistake. We signed with—”

I stepped forward before Martin could be generous with patience. “There’s no mistake.”

All three turned. My mother’s face did the math where the variables were me and unbelievable. “Nora,” she said, the way someone says no when they don’t want to knock the glass off the table.

“I own the company that owns the trust that holds the note on this house,” I said. “And your pipes are about to burst.”

It’s a remarkable thing to watch a story you’ve been a supporting character in for three decades flip to the paragraph where you’re the point. Everything slows. Everyone stares. Even the heater appears to pay attention.

“I pay the mortgage,” my father said, voice tipping into indignation. “Have for thirty years.”

“You did,” Martin said, not unkindly, “until the refinance. The new note consolidated your debt and paid off the lien. The trust—”

“The trust,” my mother repeated, species of a thing she thought she understood via television. “But why would—”

“So your interest rate would stay low,” I said. “So you could keep the house when the balloon payment came due, Dad. So you wouldn’t have to sell the only place any of us knows how to navigate. Because I got tired of waiting for someone else to make sense.”

There was a quiet you could set a tea cup on. Then the sound of water shifting in a pipe behind the far wall.

“Move,” Vaughn said, and went for the valve.

They did. We all did. For all her love of refinement, my mother has the good sense to get out of a tradesman’s way. In under a minute, the hiss turned to nothing and the house survived the morning.

When we came back inside, the kitchen had a different smell: of fear, of hollandaise curdling, of pancakes going from golden to “we’ll call it rustic.” Brianna and Mr. Townsend were dressed for brunch in matching small plaids. She had already begun performing panic—hand to throat, oh my god, what a mess.

“What is happening,” my mother whispered, to no one in particular. “What is this?”

“This is an inspection,” I said. “And a conversation. I’ll do the latter quickly because you have a reservation. In two hours, you’re going to drive to Tannenhof Lodge & Spa for your long-discussed, much-photographed Christmas brunch. You are very excited about the ice sculptures. When you arrive, you will walk into the lobby and the general manager will greet you by name. He will tell you the owner is delighted you’re here,” I added, because cruelty is a drug and I am trying to quit. “Then he will seat you in the salon overlooking the rink. There will be a moment where you, or Brianna, or Mr. Townsend—really anyone—asks who the owner is.”

“And then what,” Brianna said, eyes sharp as garland. “You’ll pop out of a cake?”

Ada snorted. I didn’t. “I’ll already be there.”

“You don’t own—” Mr. Townsend began, then stopped because he is smart enough to be poor.

“The snowcat out back,” I said, almost kindly. “But I own the rest. Through an intermediate vehicle. It’ll be fun for you, actually, Townsend. A teachable moment about due diligence and contempt.”

“You can’t…” my father said, then trailed. You can’t had been the family’s way of trying to keep me small: you can’t quit that job, you can’t “waste” your degree, you can’t show up in boots, you can’t stay unbowed. They never finished the sentence because reality had always finished it for them.

“Nora,” my mother said, the warble in her voice the sound of a grenade pinned with a bobby pin. “Are we being punished?”

I looked at her and felt the soft place behind my sternum that never fully hardens. “No,” I said. “You’re being shown. There’s a difference.”

“Shown what.”

“That the garage door swings both ways.”

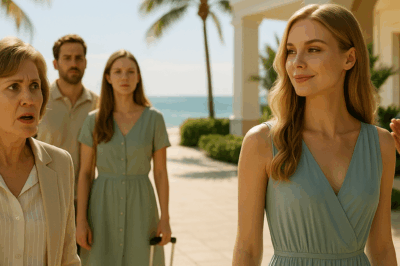

Two hours later, the Anderson family caravaned up the mountain road toward the lodge that had lived in our group texts since Labor Day: Do we want the 11:30 or the 1:30? Do they validate? What does one wear to “alpine chic”? The snow had decided to mean it; the spruce wore white like a vow.

I arrived twenty minutes early and let the general manager, a man named Hal who looked like he’d been born in a tuxedo, walk me through the layout. “We have the salon arranged as requested,” he said, with relief that read as gratitude. “The Brumfields are in the corner. They are already on their third Bloody Mary and they have opinions about celery.”

“Don’t we all,” I said, and he actually smiled. We bent over the seating chart together like co-conspirators. “Put Brianna and Townsend here,” I said, marking the table nearest the fireplace. “My mother here, where she can see the rink. She likes to believe in stories on holidays.”

“What about you?”

“Give me the perch,” I said, pointing to the small balcony table above the salon where owners sometimes watched events without being watched in return. “I want to arrive, not appear.”

“Very good.”

I took the back stairs and stood behind the lace of a fern, watching people be themselves. It is my third-favorite sport.

The Andersons arrived with the usual velocity—Mom’s fur, Dad’s scarf, Brianna’s entrance like she’d invented it. “Reservation for Anderson,” my mother announced.

“Welcome,” Hal said, the word landing like surprise. “We’re honored to have you. The owner asked me to extend her personal greetings.”

Brianna’s gaze flicked up toward the balcony at owner. I stepped forward then, slowly, because if you have ever rehearsed a moment in your head for ten years and it finally arrives, you shouldn’t sprint through it.

“Hi, Mom,” I said, leaning on the railing. The room did that collective inhale people do when they are both embarrassed and thrilled.

Brianna’s mouth made an O. Mr. Townsend’s face went corpse-grey, then the exact pink of humiliation. My father’s jaw worked silently. My mother’s hands went to her pearls as if the truce flag needed reinforcement.

“Welcome to my lodge,” I said.

“You—” Brianna began. It’s possible she meant can’t. It’s possible she meant won’t. It’s possible she meant help.

Hal stepped sidewise, admiration hidden in hospitality. “Mrs. Hale is the majority owner of Tannenhof Lodge & Spa,” he confirmed, as if the room had asked collectively. “She purchased the property last quarter.”

“You’ve been so excited about this place,” I said to my mother, because it is dangerous to let only sharp words out of your mouth. “It truly is beautiful. The pool upstairs is warm enough to make you cry.”

“Why,” she said finally, a question with too many possible endings. Why didn’t you tell us. Why this way. Why now.

“Because this is the only way you hear me,” I said gently. “When I knock on the kitchen door, nobody moves. When I open the front door, suddenly we’re listening.” I looked at my father. “I bought the house note so you could keep 217 Willow when the balloon payment came due. I brought a plumber on Christmas morning so your pipes didn’t burst. You responded by giving me a cot in the garage. I am handing you a table now and asking you to sit down.”

At the word house, my father’s face did a complicated thing with shame and pride that looked like love if you didn’t stare too long.

Brianna reached for the only thing she trusts: offense. “You could have just asked me to move over on the pull-out,” she said. “You always have to make a production.”

“I have always kept my productions in the black,” I said. “Which brings us to you, Townsend.”

His napkin was clenched between both hands like a surgeon about to make an incision he didn’t want to own. He looked up.

“There’s a pre-board at eight,” I said. “Your Q4 projections are soft. Your ‘efficiency’ pilot cost three million. I’ve read the emails where you use my anonymity to call me the girl behind the curtain and the ghost. I won’t embarrass you here.”

He swallowed. If he could have rolled under the linen without disrupting the table setting, he might have done it.

“You can all have a terrible day,” I added, sweeping the room with a glance, “or we can have exactly the day you all claimed to want. There is trout on the menu that will make you kiss the table. The pianist takes requests that aren’t ‘Let It Go.’ The rink is smooth as grace. Choose.”

You would be amazed how quickly people will choose joy when you remove their mirrors.

Hal led my family to their table with the kindness that makes strangers feel human. I came down the side stairs and stood at the threshold. My mother looked at the ice. “Your father proposed to me at a rink,” she said quietly, to no one in particular. “I was wearing mittens.”

“If you want mittens,” I said, “we can get mittens.”

She looked at me and there it was—the smallest, most expensive present of the day—the gratitude people keep in a drawer and are afraid to take out.

“No mittens,” she said, and patted my hand like a note she’d decided to save.

The meal was astonishing. The trout did make me want to kiss the table. Brianna forgot, for twenty minutes, to perform. Caleb asked me about my fund without trying to turn it into an elevator pitch for a cryptocurrency his friend was flogging. My father told a story I had forgotten about the year the tree fell across the driveway and how we all dragged branches together, laughing, because none of us wanted to admit we were cold.

At two o’clock, I excused myself from coffee. “I have a phone call,” I said, and everyone knew what I meant.

In the owner’s office upstairs, Susannah sat with Hal and watched me put my elbows on my desk and not on my heart. “You were exquisite,” she whispered. “Also: Townsend is sending you five calendar invites like prayer.”

“I know,” I said, and hit accept on one of them. It felt like a mercy disguised as steel.

“You don’t have to be there,” Hal said. “We can run it. You can run downstairs and skate or whatever people do when they have their families near them and Christmas turned the color you hoped.”

I looked at the ceiling. It had beams older than every grudge I’d ever carried. “I’ve spent five years letting men like Townsend talk at me because it was useful. I would like to talk at him now,” I said, and stood. “After that, maybe I’ll skate.”

We did board. We did not fire anyone. We did what good owners do when they have been poor and remember it: we drew lines, set milestones, traded contempt for clarity. Townsend apologized exactly once, and it did not come with a clause about nonetheless. When you run a room well, even your enemies want to do right so they get to sit in it again.

By four, the light had gone the color that makes pine look like something you can eat. My family put on skates and did the awkward wobble that happens before grace. Brianna clung to the rail and shriek-laughed in a way that would have annoyed me yesterday but felt like life today. My mother shuffled and found a rhythm. My father held his hands out like victory. I laced my skates alone, without performance or audience, and stepped onto a sheet of ice someone else had made possible for me.

My mother’s voice came across the rink like a bird. “Nora?”

I turned.

She reached into her coat pocket and pulled out a single strip of fabric—wool, striped, from the box in the hall closet we all pretend not to know. “I found this,” she said. “From the year you were eight and the power went out and you insisted on sleeping in the garage because you were angry about… something I can’t remember.”

“I remember,” I said. “I was eight.”

She laughed and then did not. “I’m sorry,” she said. It hung there a second. Then: “Not for the garage. For the years I let the kitchen be louder than you.”

I took the scarf and tied it around my neck like a forgiveness. “Okay,” I said. Not because it erased anything, but because it allowed something.

Brianna skated up and crashed into us both, nearly toppling. “If anyone posts video of this,” she panted, “I will buy the internet and unplug it.”

“You can’t buy the internet,” I said.

“You could,” she muttered.

“Not with your bonus,” I said, and we all laughed, the kind of laugh that comes when the truth stops being a weapon and starts being a weather report.

Later, when the rink lights came on and made the snow look like it was applauding, Paige found me near the fire pit. She put her hands near the flames and stared at them like they were telling her a story. “I still don’t like that you did it this way,” she said. “The… theater of it. The video. The speech.”

“I’m a woman,” I said softly. “Sometimes theater is the only way the balcony hears.”

She nodded slowly. “But I like that you did it at all.” She hesitated. “And I like that you paid a plumber instead of waiting for the pipe to burst just so you could tell me I should have listened.”

“I have spent my entire life trying not to be the kind of person who uses suffering as a classroom,” I said. “I fail sometimes. I am trying to fail less.”

She surprised me by putting her hand on my forearm—fingers light, like asking before taking. “I will work one shift a month,” she said, not meeting my eye. “At your lodge. At the bar. Without telling anyone. Will you compensate me fairly so I can feel like it counts?”

“Yes,” I said, because some yeses you should always be ready for.

“And will you come to dinner next year,” she added, the words almost lost in the hiss of the fire, “and sleep in the guest room without having to win it?”

“I will,” I said. “If you make the hollandaise.”

An hour later, I watched my family drive away down the mountain road. The lodge lights made halos in the snowfall. My phone buzzed in my pocket. Susannah: You did good, boss. Merry Christmas.

I stood under the eaves and listened to the sound that came after a day like that: not silence, exactly, but the world exhaling. The garage heater at 217 Willow would hum tonight but nobody would sleep on a cot. The lodge would reset the tables and the skates and the next morning would be a new number on the calendar and the same work in my spine.

I looked up into the falling snow and thought of all the rooms I had built for other people to feel less alone. Then I went inside and made sure the night staff had dessert.

There are a thousand ways to end a story like this, but here is the one I picked: the next Christmas, my mother handed me a mug in the kitchen—the good cocoa, the cream she buys just for the holidays—and said, “Guest room’s yours. If you’re willing to share it with a space heater, because—” she rolled her eyes “—Brianna is here and she is pregnant and apparently the office is now a nursery.”

“I’ll share,” I said, and we both smirked at the ghost of a garage door we could no longer hear.

Sometimes the people who banish you to the cold end up asking you to help them light the stove. Sometimes you say yes. Not because they deserve warmth. Because you do. And because you’ve learned the most tremendous secret—bigger than balance sheets and shell companies and the satisfaction of watching a man who called you a mailroom candidate realize you sign his checks. The secret is this: the life you own is the life that can’t banish you anymore.

Part Two

By New Year’s, the story had done its laps around town the way gossip always does—faster downhill, slower going back up the hill where the facts lived. The version with the fewest sharp corners was this: the Anderson girl people thought was a teacher in a threadbare cardigan owned the house her parents lived in and the lodge where everyone had planned to show off their coats; she’d done some kind of boardroom sorcery; and—my personal favorite—she’d “made the plumber come on Christmas, like a Christmas Carol with a wrench.”

The truth was both more boring and more volcanic: numbers, signatures, voicemail transcripts, balance sheets, and the quiet way a family has to rearrange itself when the story it has told about itself cracks down the center like ice.

The first Monday of January, I sat at the head of Northline’s glass table and let Mr. Townsend lay out his case for why his Q4 should be judged on dreams instead of math.

“We were building capacity,” he said. “Seeding future efficiencies.”

“Future efficiencies do not pay current vendors,” I said. My tone had the smooth finish of a set of kitchen knives. “Let’s talk about timelines. And accountability.”

He nodded in a way that meant please don’t fire me in front of my reflection. Susannah slid a paper across the table to him: a six-point corrective action plan with dates, targets, a mentor pairing, and—my favorite clause—a requirement to spend two full days shadowing our front-line hospitality staff, including a breakfast shift with Dana in housekeeping who has a PhD in seeing who people really are in under thirty seconds.

“We’ll measure you on improved margins, not improved metaphors,” I said, and moved us on.

I didn’t fire him. Not because he didn’t deserve the kind of wake-up that comes with a cardboard box, but because I’m allergic to performative decapitations. There is a difference between revenge and repair. My father taught me that at a hardware counter without ever saying the words.

“What about your sister?” Susannah asked later that week, when the two of us were walking laps around the mezzanine to bleed off the energy of not shouting at a grown man.

“She has six months,” I said. “Real milestones. Real support. Real consequences.”

“You’ll do it?” Susannah’s eyebrows described surprise and approval.

“I will,” I said. “Not because she’s my sister. Because she’s a human who has never been asked to run toward better. I’d like to see what she looks like when she’s not running away from worse.”

By February, we had a rhythm that felt like something I could walk without thinking about where to put my feet. On Tuesdays, I met with a financial coach from a nonprofit and my parents at the kitchen table of 217 Willow. She came with worksheets and kindness, and they came with defense and then, curiously, a pencil.

“Zero-based budgeting,” she explained, sliding a sheet toward my mother, who looked at the boxes like a woman studying a map to a country she didn’t know you could live in. “Every dollar gets a job. You can’t spend the same dollar twice.”

“Isn’t that what credit cards are for?” my father tried to joke. It broke in the air like thin ice.

We made mistakes. My mother cried twice. My father took three walks around the block and came back with a purple face and a light in his eyes I hadn’t seen since I was twelve and he figured out how to fix the washing machine with a screwdriver, a YouTube video, and a curse. We rearranged the fridge magnets. We set up automatic transfers—their transfers this time, not mine. Under a simple written agreement Ada drafted, they retained title and responsibility. The trust kept the mortgage. I committed to nothing but honesty and one thing on paper: if they made twenty-four consecutive payments on time, the rate would drop another half point. Carrots, sticks, math.

One Tuesday, while my mother was puzzling over whether it was groceries or household if you bought paper towels and butter on the same receipt, she looked up at me with something like shy. “I found your high school debate trophy,” she said. “It was in the box with the tree skirt.”

“Why?” I said. Not where did you put it or you should have told me. Just why.

“I like trophies,” she said, then laughed because the answer sounded stupid out loud. “I like… what they say. You know? That something stayed shiny.”

“You could put it back on the shelf,” I said. “Beside the good candlesticks. The ones you never use.”

She did. That night, I watched my father dust it like he was not dusting it.

In March, Brianna appeared in Northline’s HR training room without an entourage and in flat shoes. I recognized the look on her face—the particular inflamed irritation of a person who has discovered that humility chafes.

“You wanted me to join a cohort,” she said, dropping her tote on the table like it had wronged her. “I’ll join a cohort.”

“Incredible attitude,” Susannah murmured, breezing past with a stack of folders. “Put her next to Jason. He still thinks resource is a synonym for employee.”

The cohort met Thursdays at eight a.m. and consisted of ten people we’d pulled up or in from across our companies—managers with something to prove and something to unlearn. They practiced managerial one-on-ones. They did case studies. They endured a role-play with Dana from housekeeping that made three of them cry and one of them quit. Brianna, to her credit, did not bolt. She listened too hard, wrote too much, and grimaced her way through feedback like a woman powering a cable car.

In a session on “Saying No Without Setting a Fire,” she raised her hand and said, “What if the person you’re saying no to is your mother?”

“Then you sit down before you do it,” Dana said, without looking up from the coffee she was doctoring with precisely two creams and a sugar. “Standing no’s look like fights. Sitting no’s look like choices.”

I watched the information that wasn’t a sentence travel from Brianna’s ears to her jaw and lodge there.

By April, the garage at 217 Willow had a space heater that wasn’t trying to die, a new insulated door (my father and Caleb installed it themselves using YouTube and stubbornness), and—for no reason anyone would admit—a row of hooks my mother labeled COATS in her best schoolteacher handwriting. She had swept, by choice. My father had cleared the golf clubs without being asked. One Saturday, I found him out there with Caleb and a sander, turning the military cot into a daybed with a good cushion and a blanket in a color he called “Northline Blue” because he was trying, and trying counts.

“It’ll be a reading nook,” he said, not looking at me. “For… when… if… anyone wanted a reading nook.”

I put a small lamp on the windowsill and a basket of my favorite paperbacks on the floor, spine out like candy bars. I sent him a picture of it that night with no comment. He replied with a thumbs-up emoji and then, six minutes later, “Your grandfather loved Zane Grey. I never understood it.” I wrote back, “I never will,” and we both enjoyed being ourselves.

The consequence people most wanted to ask about at cocktail parties they thought I attended (I don’t) was Mr. Townsend. “Did you get him?” some CFO would grin, the way boys used to ask in high school if you “got” the girl that actually got you.

We didn’t “get” him. We did something better. We made him learn the names of every person on the front desk and the prep team and the snow crew by heart. We made him spend an entire day in the laundry, moving sheets like clouds and watching Lydia—five-foot-one, sixty-two years old—fold a fitted sheet into something that made him want to take notes. We made him present a plan in June that improved margins by twelve percent without cutting one job. We made him say I was wrong once. We kept him because he was better. If he had been bad and kept being bad, we would have sent him home with his plants.

The person nobody asked about was Caleb. That felt, to me, like the real failure of those who claim they want to help. He doesn’t fit in LinkedIn. He runs his own one-man remodeling business that lives on receipts he keeps in a shoe and three very loud referrals at the diner. Nine of every ten days, he comes home with paint on his knuckles and a grin that looks like freedom. The tenth day is dark. On those days, he sits on the porch steps with a beer long enough to make the wood worry. Everybody has a tenth day. We’re not honest about it because we’ve seen what honesty costs.

In May, he came into Northline wearing his one good shirt and looking like he wanted to ask for money and forgiveness and a way out of a problem he wasn’t ready to name. Instead, he said, “Do you have any extra work? Nora, my truck…”

I didn’t hand him a check. I handed him a bid. “The lodge needs the north cabins re-sealed by July. I’ll pay Northline rates. You hire one guy who’s smarter than you. You bring me a materials plan. You bring me a calendar. You meet it. You get the cabins and the ceremony hall in September.”

He looked at the paper like it was a dare. “You trust me with that?”

“I trust you with the thing that happens when you have the deadline,” I said. “Which is that you become the person who meets it.”

He did. By August, the cabins shed rain the way ducks do. By September, he finished the ceremony hall windows three days early and used the time to teach a sixteen-year-old kid named Angel how to cut trim without swearing. Angel went home with a paycheck and the knowledge that wood will take you seriously if you do the same.

It took my mother until the lilies bloomed to call the garage what it had become: “the nest.”

“We put a basket out there,” she told me in June, like a confession. “For mittens.”

For a long time, I thought resentment was my inheritance and hospitality was the family religion I had lapsed from. The truth is more complicated and more generous: resentment is the cardboard sleeve you put around your feelings so you can pick them up without burning yourself; hospitality is the candle you light when all the bulbs have gone stupid. We were relearning both, one Tuesday at a time.

Late summer brought the baby whose arrival my mother had used as the argument for my exile last December. Oliver came out looking like a scroll of secrets and the end of a feud. Brianna refused all the gifts people tried to send that came with bows larger than the entire infant.

“We don’t need a vibrating crib!” she said to me, breathless and terrifying. “We have a Moses basket and a family.”

“You have a Moses basket,” I said. “The family is on backorder.”

We built it anyway. My father assembled a hand-me-down glider with a hex key and a curse word he apologized for with two popsicles. My mother knitted something that refused to be the size she demanded and called it a shawl so it could assume its own dimensions. Caleb installed a dimmer in the nursery so the night could be less loud. I sat on the floor and folded tiny onesies into piles that future Nora—five-year-old’s favorite babysitter—would appreciate. We did not discuss my balance sheet. We discussed diaper rash and Danish butter cookies and whether it is legal or moral to love your child more when it is asleep (it is both).

Brianna did the thing women are finally doing in daylight: she asked for help. Out loud. Without apologizing. She told Mr. Townsend to take his “urgent” and put it on a shelf while her stitches healed. When she returned, she said the words that had previously only lived as Instagram captions: “My brain is different and I’m tired and I still have ambition.” We fitted her schedule around sprints and naps. We let the work sit on the days it made faces. We passed the baby down rows of project managers like a loaf of bread.

Dana showed up to the baby shower with a gift that wasn’t on the registry. “It’s for you,” she told Brianna, tapping the ribbon. “It’s a No. You keep it in your pocket and you hand it to people who think you were born to hold their Yes.”

Brianna cried. Every time she took it out, she cried again. Men learned to back up a step. That is workplace safety.

Fall slid into the creaking weeks of November, where gratitude is a noun that won’t sit still. The lodge did a brisk business in couples with complicated relationships to cranberry sauce. I spent three days in New York closing a deal that made the news and two days at a school board meeting trying to keep a middle school robotics club from losing their space to a fund-raiser’s idea of a reading nook. I prefer the latter, even when I lose.

The second Tuesday of December, my mother called and said, without preamble, “I am reserving the guest room for you.”

“I can afford a hotel,” I said, reflex and armor and truth.

“I know you can,” she said. “I am reserving it anyway.”

“Okay,” I said, because I am not in the habit of refusing outcome when the intent is finally good.

We did Christmas the way families do when everyone is both on their best behavior and tired of pretending: we made too many cookies. We ate the broken ones. We let the conversation wade into real water and then come back to shore when it got cold. We skated on the rink at the lodge and nobody asked who owned it anymore; we just skated. We let Mr. Townsend show up for cocoa and redemption. He never said thank you for the corrective plan. He didn’t have to. His numbers did.

On Christmas Eve, I stood in the garage—the nest—and looked at what we had made from humiliation, distance, and two coats of paint. The little lamp cast a circle of light on the page of a book someone had left open—Zadie Smith this time, which meant my mother had been out here trying. The hooks held four coats and a tiny sweater none of us could stop picking up. The heater hummed like a thing that had changed sides.

Brianna opened the door with her hip and walked in with Oliver swaddled like a burrito. “He wouldn’t sleep without the machine,” she said, rolling her eyes at herself for saying a sentence we both would have mocked two years ago.

“Give him here,” I said, and took him. He weighed less than my guilt and more than my pride. He smelled like warm milk and the future.

Brianna looked around. “Do you think,” she said, gesturing at the woven basket under the daybed, at the paperback pile, at the garage door that had been insulated like it was something we loved, “that it was always supposed to be this? A place we made on purpose instead of a place we shoved someone?”

“I think,” I said, adjusting Oliver against my shoulder until his breath settled into the rhythm of a room that wanted him, “that almost nothing is supposed to be what we make it and almost everything turns into what we ask it to if we keep showing up.”

“That’s a lot of thinking for one garage,” she said, and laughed through her nose.

“Don’t get used to it,” I said. “Next season I’m turning this into a wine cave.”

“You don’t even drink wine.”

“I know,” I said. “I’ll hire a man named Pierre to talk about legs.”

She snorted and then was quiet and then wasn’t. “Thank you for not making me sleep out here this year,” she said, the joke like a fence you can sit on to look at the field beyond. “And thank you for not making me say the sentence I am trying to say badly.”

“You’re welcome,” I said. “And I see it even if it doesn’t come out right.”

My mother appeared in the doorway as if conjured. She was holding two mugs of good cocoa. “Guest room’s turn-down,” she said, with ceremony. “And the hollandaise did not break.”

“You used a blender,” I said.

“I am a convert,” she replied, loftily. “Call me Martha.”

We stood there, three women who had once made a trap out of a holiday and found a table instead, and clinked our mugs gently so as not to wake the baby. Through the wall, I could hear my father turning on White Christmas and then pretending he hadn’t when someone would inevitably groan. Through the heater’s hum, I could hear my own heart and it wasn’t trying to outrun anything.

Here is the ending I earned and therefore choose: I slept in the guest room and no one had to be banished to the cold to make a point. The plumber sent his invoice with a note that said, “Tell your dad he owes me a beer for pretending he tightened that valve.” The lodge turned a profit and a corner. Brianna kept her cohorts and her kid alive and her ambition awake. My parents paid their mortgage without my hand on it and framed the amortization schedule in the office like a family portrait. Caleb started teaching kids on Saturdays how to hang a door straight and listen harder than you talk.

As for me, I added one line to the owner’s manual of my life: Hospitality begins where humiliation ends. The garage taught me that. So did all the rooms I have had to walk into and set on fire so they’d be warm enough for the people I love to learn to sit in.

When people ask me now—at dinners, at board tables, at the front desk when they realize the woman in boots and a ponytail is signing their bonuses—Is it true your family once made you sleep in the garage on Christmas Eve?—I say, “Yes. And now we keep the sleds there.”

Sometimes they laugh. Sometimes they don’t get it. Sometimes they whisper to themselves because it is easier to narrate someone else’s lesson than to admit you need one. I don’t correct them. I don’t need to.

The heater hums. The baby sighs. The cocoa stays warm enough between sips to feel like a choice. The house creaks the way old houses do when they settle into themselves. The lodge lights wink through the trees. And I sleep like people sleep when the rooms they own finally fit the size of their life.

END!

News

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… ch2

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… Part One The…

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped “She’s My Boss”… ch2

My Father Disowned Me Before Mom’s Birthday — Then My Sister’s Boyfriend Gasped, “She’s My Boss”… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load