My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls “Help with the Funeral!”

Me — “My MIL died 3 years ago.”

Part One

I was forty the year the phone rang with a voice I had prayed never to hear again.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

My name is Leah Forest. I’m a senior manager at an advertising agency now, the kind of woman who knows how to build a brand from three adjectives and a mood board; the kind of woman who carries a pen that never explodes in her bag because she has learned, painfully, what happens when you let mess happen quietly and then call it normal. I grew up without a mother—at least not one who stayed. My biological mother drifted out of my childhood like perfume from an open door after a party, leaving behind a father who tucked notes into my lunchbox and taught me how to fix a leaky tap with Teflon tape and patience.

I don’t remember my mother’s face as much as I remember my father’s hands. They were gentle with wood and stubborn with the world on my behalf. We were happy, which is to say: we were tired in the evenings and safe at night and made jokes no one else would have laughed at.

When I was twenty-six, I mistook a promise for a plan.

Mason Stones introduced himself at a friend’s barbecue with the unabashed confidence of a man who sells televisions for a living and believes in picture clarity as a metaphor. “Leah, marry me,” he said half a year later under a string of fairy lights in a garden that wasn’t ours. “I’ll make you happy.”

It took a while to see that some verbs should be conjugated together or not at all: We will make each other happy. My father shook Mason’s hand with a grip that said, Take care of her, and I said yes because I thought I was joining a team.

“What about where we’ll live?” I asked one night, opening our future like a map.

“Huh?” Mason blinked. “We’re moving in with my mom, obviously.”

“Obviously?” I repeated, because I had missed the part of our courtship where he’d cast his mother as the third lead in our marriage.

“My dad died early,” he said with the noble air of a man volunteering for a thing he hasn’t been asked to do. “It’s pitiful for Mom to be alone. We’ll live at her house. You can’t say no after all these plans. That would be cruel. She’d cry.”

When guilt is the first tool someone hands you, you don’t realize it isn’t a hammer until you’ve smashed something you can’t repair. I pictured the day I’d seen his mother—a woman with neat hair and a voice wound tight around polite remarks—and told myself I could do this. Families were compromises that became stories you brag about later, right?

On moving day my mother-in-law—Mila, which sounded softer than she was—stood in the doorway with her arms folded like a curtain rod and declared, “From now on, you will handle all the housework, Leah.”

“I’ll… help,” I said, because I still believed in teamwork. “But I work full-time.”

“You’re the daughter-in-law,” she said, already turning away. “That much is expected. Any complaints?”

Mason, who had wanted me to keep working because he liked the way my title looked next to his on RSVP cards, kissed my cheek and said nothing to his mother as she walked away. I told myself beginnings are awkward. I told myself I would earn my place.

Here’s the schedule I kept for three years: up at 5:30 to sweep and wipe and place breakfast on the table like an apology for being alive; commute; meetings; deadlines; corralling creatives with more ideas than discipline; home to shop, chop, cook; dishes; laundry; a cheerfully staged “How was your day?” that often answered itself. Days had a rhythm. Nights had a script.

Mila was sloppy—plates left in odd places, cups abandoned on armrests, wrappers tucked into cushions like she was planting a forest of litter that only I could see—and yet she was a theatre critic of my housework. “What’s for dinner?” she would call from the sofa, voice floating above daytime TV laughter like a drone.

“Grilled fish,” I’d say, easing a pan onto the stove like I was setting a baby in a crib.

“Fish?” she scoffed. “We’re not poor.”

“It was fresh and on sale,” I said. “And fish is healthy.”

“Don’t treat me like an old lady,” she snapped. “I want meat. Make it again.”

“We don’t have meat right now,” I said quietly.

“Go buy some then. Hurry.” She turned back to the TV, her smile reserved for strangers.

I looked at Mason. He looked at his phone. “Just do as Mom says,” he muttered, not looking up, the corners of his mouth soft with disinterest.

Time. Work. Chores. Repeat. You can be trapped by a routine you built yourself, brick by brick, obligation by obligation, until the walls meet and you call it a home because you don’t know what else to call it.

A year in, the questioning began. “Are you pregnant yet?” Mila asked, tapping her fingers on the table like a metronome for my body.

“Not yet,” I said, because that is what you say when you have learned the limits of small talk.

“It’s been a year,” she said. “Too slow.”

“We have our own pace,” I said, swallowing the rest: and our own doctor who said there’s no problem.

“I don’t want pace, I want a grandchild,” she hissed. “Hurry up.” She left the room as if she hadn’t spoken at all.

The months that followed made me thin in ways you cannot weigh. Fertility treatments are hope condensed into syringes and charts that trick you into thinking bell curves and human yearning are part of the same mathematics. Each time I bought pads at the drugstore, Mila sighed theatrically. “So that’s why you can’t have kids. It’s your fault.” She said it like she was diagnosing the weather.

I pretended my father’s pride still held me upright. I told myself you can’t go home and erase a wedding photo because someone else decided you weren’t enough.

Two years. Then three.

At dinner, she asked again. “Pregnant yet?”

“No,” I said, a bite of rice turning to chalk in my mouth.

“Useless wife,” she sneered. “Barren.” She said the last word like she was spitting out a seed.

“Mila,” I said, surprising myself with the sound of my own name for her. “That language hurts.”

“You can’t even get pregnant and you’re talking back?” She turned to Mason. “We don’t need a wife who can’t give us children, do we?”

“Yeah,” he said, not unkindly, not anything at all really. “Guess we don’t.”

“It’s clearly Leah’s problem,” Mila declared. “I’ve wasted my youth waiting.”

“Poor Mason,” she added, patting his shoulder while looking at me the way you look at a stain you can’t get out. “Do you know they say after three years childless, it’s time to leave?”

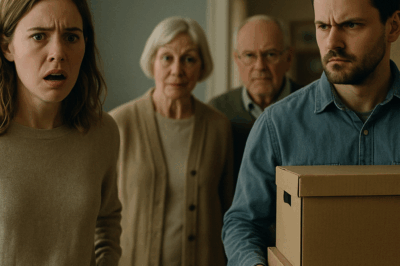

“What?” I looked at Mason. I wanted his face to say anything other than agreement.

“Let’s get a divorce,” he said, shrugging like he was ordering a second beer. “I want to be with someone cuter. Someone who can have children.”

He slid a completed divorce form across the table like a restaurant bill. “Pack your things and get out. I don’t want to see your face.”

I signed. I packed. I left.

Mila followed me to the door, eyes bright with victory. “It’ll be interesting to see how a barren woman in her thirties manages after divorce,” she said. “Don’t ever show your jinx of a face here again.”

I moved my suitcase to my father’s guest room and buried my head under the pillow like a teenager who had learned adulthood could be worse than high school. Then I went back to work and built campaigns like lifeboats. It turned out that when you remove nightly ridicule and replace it with silence, you can hear your own talent again. My clients noticed. My title changed. My paycheck did too. The space where a child might have grown remained empty, but other spaces filled: travel, friends, weekends that didn’t feel like triage.

A few years later, Owen Forest—a project lead from one of our biggest accounts, whose emails were always precise and whose jokes in meetings always took the sting out of a late change—asked me to dinner. “I’m serious about marriage one day,” he said, the kind of man who puts a period at the end of a sentence and means it. “Would you consider it? Us?”

“I was divorced,” I said, putting the word down between us like an honest napkin. “It was… brutal. My mother-in-law made our life a contest I never entered. I can’t do that again.”

“Then we won’t,” he said simply. “Would you meet my mother? She’s very ordinary. You’ll like her.”

I braced myself for the one-two punch of polite interrogation and pointed concern. Instead, I met Sadie, who opened the door with flour on her hands and a laugh ready for anyone she liked. “You’re Leah,” she said, as if Owen had spoken of me as a person and not as an acquisition. “I’ve heard the important parts: smart, kind, makes my son less serious. Come in. Do you like pie? No? I’ll convert you.”

That night, halfway through an apple pie that tasted like forgiveness, she touched my wrist. “I know you were married once,” she said. “Do not tell me the sad parts unless you want to. You’re the person Owen chose. That’s enough for me. I’m happy if you are. I promise I will not make your life my project. But if you need anything, for any reason—ever—you ask me. I will learn how to be the mother-in-law you deserve to have.”

I went to the bathroom, shut the door, and cried so hard I didn’t recognize the sounds I made. On the way home, I squeezed Owen’s hand. “Your mom is… what I always wished a mother would feel like,” I said. “Ideal without pretending. Soft without being a doormat. Firm without being a wall.”

“You’re both lucky,” he said, and I kissed him at a red light because I wanted to.

We married. Not in a way that required anyone to pretend. We rented an apartment near Sadie’s bungalow but did not live with her. We ate dinner at her table once a week because she made a stew that tasted like purpose. She never came over unannounced. She called me on my birthday and on random Tuesdays to say “I thought about you when I saw a woman in the grocery store wearing shoes I know you would have loved.” She never said “when will you give me a grandchild,” because she knew our bodies aren’t vending machines and because she respected our privacy as if she had invented courtesy and was obliged to enforce it.

A year into our marriage I stood in a bathroom staring at two pink lines and learned that biology doesn’t care about other people’s curses. When we told Sadie, she put her face in her hands and laughed, then cried, then smoothed my hair and said, “I would have loved you regardless. But I will also love this baby the way I would have loved a lottery win I didn’t buy a ticket for.”

Our daughter was born with a scowl like her father’s and a scream like her mother’s. We named her June, because she brought summer with her even in November. Sadie came over every Wednesday to hold her so I could shower, or nap, or realize my bones had been hungry for quiet all along. “You’re doing beautifully,” she said, regardless of whether I was wearing matching pajamas or the delirium of new motherhood as a hat.

Seven years passed like water filling a well—steady, useful, a resource you learn not to take for granted. June grew into a five-year-old with a fondness for worms and a talent for telling knock-knock jokes that never knock or answer. Work remained busy in that way that makes you grateful for things like calendar reminders and coffee. Sadie got sick in our third year of marriage—illness doesn’t care how much you love a person. She died peacefully in a room that smelled like lemon and hand cream, holding my hand. “You made me a grandmother,” she whispered. “You made me a mother-in-law worth forgiving. Be happy. That will be how you thank me.”

I carry her last words folded in the pocket of every day.

Ten years after I left Mason, my phone lit up with an unknown number that called again and again until anxiety made me answer. I assumed it was a client whose panic did not understand the concept of office hours. It was a ghost.

“Leah,” said Mason’s voice, warbled by either poor reception or poor self-control. “It’s me.”

Old reflexes fired: check-is-June-okay, check-is-Dad-okay. Then anger rolled in, more patient than rage, more reliable.

“Actually, Leah,” he said, and I heard the wet hitch of a man trying to whip up tears like eggs. “I have some unfortunate news.” He sniffed theatrically. “Mom. Mom just passed away.”

I didn’t say I’m sorry, because I was not. I didn’t say are you okay, because he would have heard it as a bridge when I meant it as a boundary. I said nothing at all.

“But there’s no time to be sad,” he rushed on, relieved to be narrating and not feeling. “We have to arrange the funeral. Come over quickly and help.”

“Help?” I repeated, neutral as a wall.

“You were like a real daughter to her,” he added, the way a person waves a hand when they are trying to flag down a version of you that doesn’t exist anymore. “She loved you.”

“Hmm,” I said. “Your mother died three years ago.”

Silence is an instrument I’ve learned to play.

“What?” he exploded. “How dare—what kind of joke is that? My mother—the only mother of your husband—has just died.”

“Your wife’s mother,” I corrected. “Not mine. My mother-in-law died three years ago. Her name was Sadie. She taught me how to make pie crust without crying and how to love a son without holding him hostage.”

“You—” His voice shredded on its own edge. “You remarried,” he said finally, making the word sound like adultery.

“I did,” I said, and in my living room June looked up from her drawing and smiled at me with a mouth stained purple by the marker she was not supposed to use on her skin. “I married a man who knows how to stand between me and a storm and how to step aside when I reach for an umbrella. We have a daughter.”

For a heartbeat he said nothing, then: “A child? But my mother said—she swore—you were barren.”

“It seems your dear mother was wrong about many things,” I said. “This, and the definition of ‘daughter.’ It’s unfortunate she has passed. I wish your grief well. It has nothing to do with me.”

“You have no heart,” he shouted. “No tears. Where is your humanity?”

“In my kitchen,” I said, which is to say: in the place where I feed those who love me gently. “Goodbye, Mason.”

“Wait,” he said, voice thinner, like a man reaching for a rope he can’t see. “Just this once. Help. For old times’ sake.”

He heard June laugh. Voices—especially small ones—turn even men who have pretended not to care into archaeologists digging for a past they can recognize.

“Mom?” he whispered, strangled. “You had a child.”

“Yes,” I said.

“How?” he asked, and then I hung up, because some questions do not deserve answers.

I blocked his number before my body could remember the habit of making room for his demands. Then I told June we could have popcorn and apples for our movie because life is about balance.

The story did not end there. Stories like this never do, because karma is a slow clerk with a tidy book and good handwriting.

A friend told a friend who told Iris (the gossip chain is an ancient machine, sacred and reliable): the funeral was small. Mason stood beside a casket and learned that being disliked is more expensive than flowers. People came because obligation wears a suit. They left quickly because relief doesn’t. The debts arrived next—not as mourners, but as a parade. Mila owed money. She had borrowed in ways that do not come with sympathy cards. Mason inherited the ledger with the funeral home receipt, and the legal word obligation for once meant what it was supposed to. The house sold for less than he hoped. He moved into a small apartment with a door that sticks in summer and a heating system that clicks like guilt in winter. The debt collectors knocked in rhythms he probably learned to dread like alarms.

I do not feel victorious. I feel… accurate. The universe noticed. It responded with the kind of justice we call poetic when we pretend the world is a writer.

Sadie’s grave is under a maple that remembers how to cast shade politely. I bring her peonies in May and mums in October and talk to her while June picks blade-bound bouquets of grass. “I am trying to be the mother you were to me,” I tell the stone. “I am trying to be the daughter you deserved.”

Owen squeezes my hand and tells me I am. My father brings thermoses of coffee and tells June stories about a grandmother she will know only through casseroles and jokes and a pie crust recipe written in curls like a child’s handwriting. We go home to a kitchen where I do not dread footsteps in the hall.

I have learned that family is not a loan; it is an investment—one you make and tend and sometimes uproot for the sake of the garden.

Sadie’s last words were permission disguised as blessing. “Continue to live happily,” she said, a spoon’s clink in a quiet kitchen. “That will be how you thank me.”

I do. I will. I am.

And when the phone rings—inevitably, inconveniently—I let it go to voicemail, because there is a difference between being reachable and being available. Because there is a difference between the past knocking and the future opening the door.

Because the only mother-in-law I will ever call mine is three years gone, and yet somehow, still here, every time I cut the butter into the flour and refuse to be cruel to myself if the crust cracks.

END!

News

My husband: “Your family home? I pay, so I rule!” he sneers, moving his mom in. CH2

My husband: “Your family home? I pay, so I rule!” he sneers, moving his mom in Part One The evening…

My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and… CH2

My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and… Part One…

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house. CH2

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house Part One “Did you really think…

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: ‘Move in with My Parents or Divorce!’. CH2

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: “Move in with My Parents or Divorce!” Part One The…

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything. CH2

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything Part One The worst…

My Daughter Called Me a Lazy Stay-at-Home Mom, So I Revealed My Secret Business Empire. CH2

My Daughter Called Me a Lazy Stay-at-Home Mom, So I Revealed My Secret Business Empire Part One I never planned…

End of content

No more pages to load