My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know…

Part One

My name is Olivia, I’m thirty-two, and if you asked me what I do, I’d still say “caregiver”—even though, for three years, my world had been compressed into the radius of a stroller, a sink, and a little girl’s arms around my neck.

I grew up wanting to be useful. I took the vocational program straight out of high school, passed the licensure exam, and started working in elder care at twenty. It was exhausting—lifting, changing, listening, being present for goodbyes—but when a patient squeezed my hand and whispered, “Thank you, sweetheart,” the fatigue would pull back like a tide. Usefulness, I learned, could buoy you. It could also drown you if you forgot to come up for air.

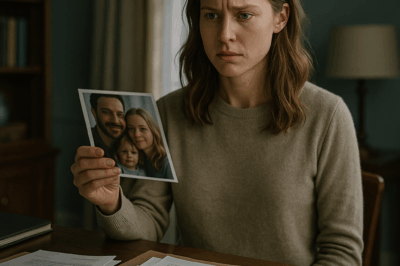

I met Liam at a mixer a coworker dragged me to. He was the handsome, quiet type until we walked to the station and discovered he wasn’t aloof, just shy. He laughed the way shy men do when they realize they are safe: freely, almost boyishly, relieved. We started dating. We married a year later, and the day after we moved into our rental, a friend pulled me aside and said, “You know he was seeing someone else when he started seeing you, right?” I felt the floor tilt.

He cried when I confronted him. He said he had broken it off. He said he’d chosen me. He said, “That was before you.” I told myself we all make mistakes in our twenties. I told myself I was the woman he’d grow with. It became the first story I learned to tell myself because it was what I needed to believe.

For a while, our life fit the brochure. On our days off, we sat shoulder to shoulder on bleachers at baseball games and yelled for teams we didn’t know the names of an hour before. After a game, on a whim, we bought a sports lottery ticket for the first time from a little booth tucked beside a souvenir stand. The numbers hit a small prize—just enough to send us giggling to a diner for pie and cheap coffee—and it became a running joke: if my horoscope said Aries was lucky or if the cashier gave us the right kind of smile, we’d buy one ticket, not the kind that asks you to be foolish, the kind that lets you be hopeful for a minute.

Year four, we had finally started talking about what would happen if our wanting became waiting. Fertility treatments were an option our wallets and our hearts were debating when I took a test in a bathroom with bad fluorescent lighting and nearly cried at the second faint line. At the obstetrician the next day, the doctor pointed at the tiny flicker on the screen and said, “Congratulations.”

I texted Liam in the waiting room: I’m pregnant. Fifth week. Once we’re past the first trimester, let’s tell everyone. He responded in under a minute: Really? That’s great. Thank you. Be careful getting home. He was not a fast texter. That day, he was.

Our dinner that night tasted like listening. We played the old game: boy or girl? Liam said he’d be happy either way but joked that he’d probably cry the day a daughter got married. I said if we had a daughter, I’d be able to talk to her about love; if we had a son, Liam could teach him to make pancakes on Sundays. Neither of us said the thing we both desired more than anything else: a healthy baby and a healthy me.

Pregnancy was both hard and lovely. My back ached, and my ankles figured out how to be ankles and water balloons at the same time. I learned the absolute best way to sleep is “however you don’t cry.” I also learned that when Liam rubbed my feet without being asked, I could forgive almost anything.

We named our daughter Charlotte when they placed her on my chest—a perfect stranger whose face already lived in the room of my heart. We were going to be okay, I told myself. We had made a person. We would remake ourselves into the people she needed us to be.

And then the seams started to split.

Before I got pregnant, we both worked full-time. That came with an obvious fairness: if two people bring home paychecks, two people split bathrooms and dishes and laundry and all of the domestic tasks that no one pays you for. After I gave birth, the caregiving job with twelve-hour shifts and nights broke my body’s math. I quit, telling myself it was temporary. “You were home today, weren’t you?” Liam started to say when he wanted to remind me of my new job. “Why didn’t you even clean the house? You must have had free time.”

Free time, I wanted to say, does not exist when a newborn believes you and only you have the magical object she calls “milk.” Instead, I adjusted. Again.

Housework partners became housework verdicts. “This is bland,” he said, pushing back from the table after a bite I had cut into polite pieces. “I can’t eat this.” When I told him I was trying to cook with less salt because his blood pressure readings in the company health screening had creeped up, he told me to shut up. He started to use words I had never heard directed at me. Useless. Stupid. “If I hadn’t married you, no one would have picked up a woman like you,” he said one night, half drunk on his own contempt.

He was gentle toward Charlotte only when other people were watching. “Daddy, look,” she said once, at three years old, holding up a purple crayon drawing that looked exactly like a dragon if you were the sort of person who loves dragons. “So what?” he said, eyes never leaving his phone.

He could be charming when he wanted to be. At a friend’s wedding, he told our table, “Olivia’s a perfect wife. Best cooking, best laundry,” and our friends smiled at me with envy I did not know where to put. At home, he was a different person. On his days off, he left in the morning, came home smell of cologne and bars in the early hours, and if I asked, he said where he went was none of my business. “Be grateful an elite like me brings money home,” he said, and I learned that a sentence can render you invisible even while you are physically in the room.

Why didn’t I leave? The short answer: Charlotte. The longer answer: fear. I had a little girl with a laugh like sunshine and an appetite like curiosity. As a full-time housewife, could I give her what she deserved? Could I find a job fast enough? Could I afford piano lessons if she wanted them, or college, or braces, or any of the million little things love becomes when it grows?

One afternoon, I saw, out of habit and nostalgia, a banner in the corner of the supermarket: Lucky Day. The lottery ticket booth, wrapped in red and gold paper, the way old wishes dress up to seem new. We used to buy tickets on silly days. We used to make lists of things we’d do if ten dollars turned into an impossible number. Something in me that had been folding itself smaller and smaller for years unfolded an inch. I bought one ticket. I put it in my pocket and then in a drawer and then, after Charlotte was asleep, I remembered to check it on my phone, expecting the usual: a free play, a coffee.

I blinked. The number didn’t make sense. I counted zeros: one, two, three, four, five, six. The screen said $6,000,000. I closed the browser because that is what your brain does when it thinks the world has played a trick on it. The next morning, I opened it again. It was still there.

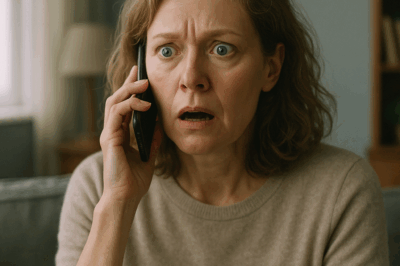

Breathless, I called a lawyer from the list a friend had given me when her marriage ended. “If you bought the ticket after the marriage broke down and the divorce is due to his fault,” she said, “the winnings aren’t marital assets. You should be beyond careful—document everything, do not tell him, and file.”

I didn’t tell Liam. There are sentences you carry with you that are too dangerous to say out loud with him in the room. I filed. I started moving boxes discreetly. When I texted to ask where he wanted me to send his things, he replied, “My bad, my bad. I’ll come get it tomorrow,” as if he had left a jacket at a bar and I was the coat check.

He didn’t show up alone. He arrived with a woman who looked like a clever marketing team’s idea of new—twenty-four, glossy, hand on her belly like a promise she had already cashed. “Nice to meet you, ex-wife,” Emma said, smiling like you’d smile at someone to whom you were about to sell a car you knew had a cracked engine block. “Morning sickness is rough. Can you hurry with the divorce? I need to be able to post about my fi—our next chapter.”

She was beautiful. She was also the woman who had used my husband’s phone to call me and say, “I’m pregnant. He’s an elite banker. I’m going to marry him. Please send his stuff. You should be grateful we’re doing this now.”

I handed the papers across the table. Liam grabbed a pen like a man being handed a golden ticket and scrawled his name as if he had practised the flourish in the mirror. “Submit them today,” he said.

“Sure,” I said, and swallowed the part of me that wanted to make a speech. There is a certain type of silence that is more satisfying than any monologue. It’s the sound a door makes when it closes gently but firmly enough that no one will try the handle again.

One week later, with the divorce finalized, I walked into the bank where my ex-husband worked because six million dollars requires appointments and counter signatures and ordinary people learning quickly how to talk to wealth without letting it change their grammar. I wore my plainest cardigan. I lined up like everyone else. I told the teller I wanted to see someone about a large deposit.

“Olivia?” Liam’s voice in the lobby was a sneer dressed as surprise. Emma was behind him, her hand on his elbow as if she were the trainer and he was the performing seal. “Miss me so much you came all the way to my workplace?” he said, too loud for a bank. “Housewife run out of money? Come to dip into savings?”

“Del—” Emma trilled, using the nickname she had stolen from my life. “Let me guess: here to beg for more alimony?”

“No,” I said. “I’m here to collect something.”

“What?” Liam asked, bored and already amused.

“Six million dollars,” I said.

Silence has a temperature. This one made the marble floor feel like ice. Emma’s smile faltered. Liam stared at my mouth like the number lived there. Then he made the sound a man makes when he realizes he is not the only person who understands how luck works. He grabbed my arm in the way he used to grab for his keys, and I pulled back.

“You never won when you were with me,” he said. “It’s unfair. You should split it.”

“You told me that being with a woman like me brings down your luck,” I said. “Maybe the reason your luck was down was because of you.”

“Olivia, I was wrong,” he said, hoarse, abandoning volume for desperation. “Let’s get back together.”

“Excuse me?” said Emma, blinking like a cat faced with a cucumber.

“Think about it,” he said to me. “We could buy a house—”

“Mr. Liam?” The branch manager’s voice arrived before I saw him. He walked out from the back with the calm of a man who has practiced the face he uses for what he assumes will be lawsuits. “Is there a problem?”

“No,” Liam said, smiling like smiles could erase behavior. “We were just—”

“I’ve heard from staff,” the manager said evenly. “We’ll speak after, in my office. Not just about this floor show, but about… other matters.” His eyes flicked to Emma and back.

“I’m sorry for the disruption,” he said to me then, bowing slightly because old institutions sometimes remember their manners. “Let me take you to a private room.”

In an office with a door that closed and a carpet that encouraged discretion, I signed forms. I didn’t take the plastic pen the way a person with a new life might cradle a baby. I held it firmly because what I was doing needed a steady hand. When the manager left me alone for a minute to fetch a supervisor, I put my palms on the desk and breathed until my head stopped being full of static.

On my way out, my phone vibrated with a message from the lawyer: The lump-sum alimony has cleared. His and hers. I didn’t smile until I was in the car. When I did, it felt like stretching something that had been cramped for years.

He called, and called, and called. I blocked him. He called again, from a different number, so many times I finally answered, not out of curiosity but out of tiredness.

“My boss says I’m a liability,” he said without greeting, words tumbling over each other in their rush to become excuses. “Demoted. Transferred to some regional branch. It’s harsh. I’ve worked hard.”

“Your boss is reasonable,” I said. “Maybe he thought someone with your lack of character could eventually bring significant detriment to the bank.”

“You don’t understand,” he said.

“I understand you’re the kind of man who tried to trade a wife for a lotto ticket and then tried to trade a mistress for a jackpot,” I said. “Now you’re learning that integrity is not the same as brand management. Take care.”

Emma called once, then disappeared into the story that women like Emma can disappear into: she resigned, she ghosted, she found someone else to promise stability to her, and yes, the whispers said the baby wasn’t Liam’s. His furious message afterward was bitter and short: She says it’s not mine. I typed not surprised and deleted it. Sometimes the victory is not typing what you think.

Charlotte and I moved to a condominium that had enough windows to teach us what sunlight feels like when it belongs to you. Six million dollars is enough to make poor choices for the rest of your life; I didn’t intend to make any. I found work again, grateful to trade the treadmill of domestic invisibility for the visible gratitude of patients who call you an angel because you remember how they take their tea.

We learned to enjoy small luxuries without worshiping them. We took my parents to Hawaii and watched my father cry at the edge of the ocean, not because we paid for it but because he had never seen a blue that big. Charlotte built sandcastles without worrying about bedtime, and I took a moment every afternoon to stand with my feet in the water and tell the version of me who bought a lone ticket at a supermarket booth that she had saved us, and that luck favors the stubborn.

I like my life now. It is not perfect. Nothing is. Charlotte still wakes at night sometimes and comes in to ask if I am there, and I say yes, and she climbs in, and I put my hand on her back and feel the small animal certainty of her breath. In the morning, I make coffee that I no longer drink alone in a house that feels like a waiting room. I walk to work past the lottery booth and buy flowers instead.

On our fridge, Charlotte taped a crayon drawing of a woman with a crown and a tiny girl at her side. “That’s you,” she said, when I asked why the crown. “Because you saved us.”

I laughed and told her queens don’t do laundry, but the truth is, I’ll wear any title she gives me, as long as it means I stayed when it was time to stay, I left when it was time to leave, and I learned, finally, that the luckiest thing about my life was never a number on a screen; it was knowing when to close the door and when to open it.

Part Two

I could tell you the rest as a series of punchlines because it’s tempting to turn our own history into a comedy when the tragedy part is over. But life after calamity is quieter than the movies would have you believe. The noise fades, and what you are left with is work, sunlight, naps, homework, bills, laughter, and the simple, stubborn courage of getting up in the morning because you have someone to make cereal for.

The bank demoted Liam and sent him somewhere far enough away that he started posting sunsets on social media with captions like fresh start. Our friend sent me a screenshot. I told her that sunset is the same sky I see, nothing special. “He’s learning to talk like a person,” she said. “Progress?”

Progress is not my problem anymore.

Emma, I heard, decided bankers are only appealing when they can hang their titles like ornaments. She told him the baby wasn’t his, which meant she either lied then or now—either way, men like Liam don’t suddenly become good at paternity math. She latched onto a new narrative, a new man, a new future she can decorate with words like destiny and meant to be. I hope, for the sake of whichever child is involved, that this time the story is kinder.

Once, in the cereal aisle, a woman touched my arm. “I shouldn’t intrude,” she said, already intruding but doing it with the contrition of a person who remembers how to be polite. “But I’m the wife of your ex-husband’s boss. I’ve heard enough to know you deserve better than apologies from strangers, but—” She paused. “You’re doing fine.”

“Thank you,” I said. It wasn’t the words; it was the sincerity. People often confuse sympathy with voyeurism. Real kindness is quiet.

On Thursdays, after the dinner dishes, I sit with Charlotte and we do a thing we invented called Plans for Later. It started as a way to lure her into practicing writing: we make a list of not-to-do chores for the future. Hers: get a dog; learn to skateboard; sleep in a tree house; make 100 cookies; go to Paris. Mine: teach you how to parallel park without crying; take you to see your first great painting; make you walk on a beach somewhere beautiful every decade; tell you the truth and protect you from it in equal measure.

We don’t write avoid men like your father because you cannot teach a small child anything in negatives. Instead, I teach her to value honesty the way you value good shoes: it will take you farther, and it will save you pain later if you invest now. I teach her that apologies are not the same as change. I teach her that secrets are allowed to be surprises, not shame. I teach her that she is allowed to be disappointed in people she loves. I teach her that the way a man treats the server at a restaurant is not trivia; it is prophecy.

Work feels good again. I anchor myself in small skills: sliding a drawsheet without hurting my back; heating a basin so a patient doesn’t flinch when I wash them; remembering whose daughter calls after lunch every day so I can move the phone closer. At the end of a shift, when I sit and take off my shoes, I sometimes remember what it was like to be young and unemployed and worried I would never catch a breath; then I look at where I am and think: I built this. Not alone—no one builds anything alone—but I did not wait for permission.

On the anniversary of the lottery, I donate a chunk of the interest to a fund for single parents at the clinic. I do it anonymously because I’m not the hero of anything but my child’s bedtime. When the receptionist says later, “Someone paid Ms. Rivera’s copay—she cried,” I feel my throat do that thing where tears and pride braid.

If this were a story I was telling someone else, I’d end here: mother and child, sunlight, the sound of a washing machine that doesn’t make you want to scream, a bank account that is both a cushion and a reminder that luck and labor can be conspirators rather than enemies. But life does not end; it loops. It offers tests to make sure you learned the lesson.

On a humid evening in August, Liam called from a number my phone didn’t know. “Charlotte starts school next week,” he said, because his mother told him. “I… I want to bring her a present.”

“Children don’t need presents from strangers,” I said, and hung up.

I made pasta with more garlic than necessary and put on music and let my daughter help me grate cheese. After dinner, we walked to the park and I pushed her on a swing until the sky turned the color painters respect. On our way home, we passed the supermarket with the little lottery booth. I squeezed her hand and said, “What should we buy?”

She glanced up at me with the authority five-year-olds have. “Flowers,” she said. “And cookies. For us.”

We did. We went home. We arranged flowers. We ate cookies. We made a mess. We cleaned it up. On the fridge, under the magnet that holds the emergency numbers, Charlotte’s drawing of me has a new addition: a dog with exaggerated ears and a grin. “Soon,” she said when I saw it. “For later.”

“Soon,” I promised.

I don’t know what Liam is doing now. I could ask; I won’t. I don’t know if Emma tells the new man the truth. I hope she does, for the sake of the child. I don’t know if the branch manager retired, or if he tells his story in bars about the day a customer came in and said “six million” like it was a spell. I don’t know if luck visits us again in quite so theatrical a way. I do know this: even if it doesn’t, we’ll be okay.

Because little did he know—and little did I know—that the thing he threw away was not a meal or a clean shirt or a housekeeper with feelings; it was the future he could have had with a woman who understands what care actually is. It is not laundry and dinner and currency. It is telling the truth even when it’s inconvenient. It is staying when it is hard and leaving when it becomes a small death. It is knowing that sometimes a miracle looks like a number and sometimes it looks like the quiet, unremarkable ways you teach a child to choose kindness.

On our mantel, next to a framed photo of Charlotte in a sunhat, I keep a folded piece of paper where I wrote something down the night I checked the ticket and understood our life had changed. It isn’t the amount. It isn’t a bank routing number. It isn’t advice. It’s just this:

The first good thing wasn’t the money. It was you deciding to save yourself.

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls ‘Help with the Funeral!’ Me – ‘My MIL died 3 years ago’. CH2

My Ex-Husband’s Mother Passed Away. He Calls “Help with the Funeral!” Me — “My MIL died 3 years ago.” Part…

End of content

No more pages to load