My ex-husband has an affair, leaves me not knowing I have $10M in savings. Upon divorce he’s shocked

Part One

My name is Charlotte Miller, and I used to be the woman who believed the last act of my life would be the sweetest.

After thirty years of marriage, our daughter, Scarlet, had married and moved across town. For the first time, the house echoed, a quiet I had long imagined we’d fill with the sound of suitcases being zipped before long weekends, and the clink of wine glasses in restaurants we’d never had time to try. I pictured us as those couples you see at airports—silver hair, matching carry-ons, conspiratorial smiles. We would travel, eat too much, take pictures that were all elbows and laughing eyes. We would spoil grandchildren and return them sticky and triumphant.

That was the story I told myself.

I’d been running on devotion for so long that when the health checkup flagged a number that should have stayed in the shadows, I didn’t make room for dread. “At this age, something’s bound to happen, right?” I said to the nurse with the kind voice, and she didn’t argue. The first scan led to a second, the kind where the technician jokes about the weather to keep you from counting seconds. I have always been a woman who solves problems; if it was something, we’d catch it early and fix it.

“Charlotte,” said the oncologist, his fingers steepled in that way people practice in mirrors when they have to deliver news. “It’s cancer.”

There is a particular sharpness to the syllables when they’re directed at you. It wasn’t a newscaster’s word anymore; it rearranged my kitchen and pulled my chair closer to the wall. Early, he said. Small, he said. Treatable, he said. Possible to remove entirely with surgery and a stint of chemotherapy. I nodded and asked the questions you ask when you want to convince yourself you are made of plans and not of fear.

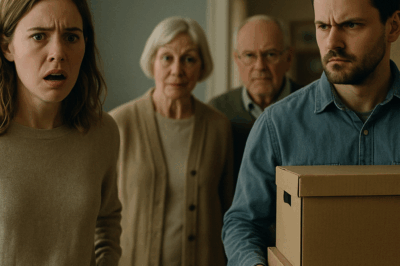

The doctor suggested I bring someone to the next appointment. I brought the man I’d shared holidays and mortgages and flu seasons with. I told him in the parking lot because the idea of saying the word under the fluorescent lights made me suddenly, absurdly superstitious.

“What the heck?” Daniel said, as if I had misplaced the car keys.

“Cancer,” I replied, and forced a smile, because I have always believed that a smile is a bridge over the impossible. “Early. Surgery. Chemo. We’ll do the plan. We’ll do it together.”

He twitched the way men do when they don’t know which face to put on. “So, surgery. Then chemo.” He nodded as if he’d been the one to come up with that sequence. “Doesn’t sound too serious, then. I thought you were going to die.”

He laughed. It wasn’t unkind, exactly. It was the kind of laugh someone uses when the punchline doesn’t land and they want to blame the delivery.

I told myself he was scared.

Two evenings later, he walked into the kitchen with a smile made of decisions. “You’ll have to fight this alone,” he said, and it took me a beat to register that he had been practicing that line.

“Huh?” I said, because eloquence can’t live where disbelief does.

“Cancer,” he said, as if explaining the news to a child. “It’s a solo battle, right? And anyway, I’m moving in with my mistress.”

There are forks of shock that land like lightning—you see the pattern, then the crack, then you count in your head and wait for the boom. “Mistress,” I repeated. The cutlery in the drawer looked like a cartoon pile of knives. “You’ve been cheating?”

“It’s not cheating,” he corrected cheerfully, like a teacher at the front of a classroom. “It’s serious. Very serious.” He said the last two words in a voice that belonged to a teenage boy with a crush and no driver’s license.

“Who is she?” I asked before I could tell myself not to care.

“Thirty,” he said, his chest puffing. “Stunning. Met her at a nightclub. Good girl, sends money to her parents.” He said it like he was reassuring me he had not, in fact, been snared by someone who’d stack him with the coats at a party and forget which bed they were on.

He fished a bankbook from his pocket and tossed it on the counter. “I guess I can give you some alimony.” Three thousand dollars, neatly printed in black and white. “I’m taking the house and the car. You’d better find somewhere else to live.”

I picked up the bankbook and looked at the number as if it were a riddle I could solve with logic. Then I looked at the man I’d grown old beside.

“What about my surgery?” It came out smaller than I intended.

He looked past me, toward the front hall mirror, the one he uses to check his tie. “If I wait to divorce you until after I retire,” he said, “I’ll have to give you half my pension. You wouldn’t want that, right? So I thought I’d move things along.”

He grinned to show me how clever he was.

He talked about time as if it were a currency he had to protect from theft. He told me he didn’t want to be a caretaker. He told me that whether he was eighteen or eighty, he would choose love over obligation.

He told me to be out in a week.

There are people who believe the worst thing anyone can tell you is that you’re going to die. I can tell you that there are worse things.

I booked a small apartment that afternoon—the kind where a high-rise window makes even the ugliest city corners look like a painting. The brochure called it a “care residence,” and it was so slick it made my teeth hurt, but the bullet points were undeniable. Twenty-four-hour nursing staff. Pool. Sauna. A café that didn’t call itself a café to try to be cute. On-site spa. A button you can press and a nurse will appear with eyes that stay on your face and a hand that is strong enough to remind you you are not just a diagnosis. If you had told me a week before that I would stand in a granite lobby and sign my name on a lease because a salesman told me I would “restore my sovereignty,” I would have laughed.

I signed.

In the new apartment, the first thing I did was call Scarlet.

“Mom, what’s going on?” she asked, her voice one word away from a scream. “You got diagnosed with cancer, you got divorced, and now you’re in a luxury apartment with a pool? Tell me a joke, because this is a sketch.”

“It’s not as dramatic as it sounds,” I said, and then laughed at the absurdity of the sentence. “Okay, it’s a little dramatic. The tumor’s small. They’re going to take it out. I pressed a button and a nurse brought me tea. And there’s a steam room that forgives you without making you confess first.”

“Did Dad give you alimony at least?” she asked, suspicion pressing against each word like an edge.

“Three thousand dollars,” I said, and put as much comedy into it as I could find. “He was very generous.”

Pause. Then: “Three thousand dollars,” she repeated, flat as a heartbeat on a screen that scares you. “After having an affair and kicking you out. Three thousand dollars.”

“He needs his money,” I said, breezy, because I needed to be the kind of mother who could poke fun at this and not be the kind who lived inside it. “It’s okay.”

“How is this okay?” she protested. “How are you in a place like that?”

“Because your mother is actually rich,” I said, and the sentence tasted like chocolate after a funeral.

She went quiet, a silence that I have learned to interpret as the sound of Scarlet looking at a map of the world she thought she knew and the pin moving a few inches to the left. “How rich are we talking?” she asked finally, with the irrepressible honesty people forget to be ashamed of in front of their mothers.

“About ten million.” I said it and heard the universe try to swallow the number and choke.

“Ten million,” she repeated. “Where did you even—? Grandpa?”

“Your grandfather’s inheritance,” I said. “I put it in the market and I didn’t tell anyone. Especially your father.” I made a face even though she couldn’t see it. “If he’d known, he would’ve quit his job the same day he bought his first midlife-crisis jacket.”

Scarlet snorted. “God, Mom. I had no idea.”

“That was the point,” I said, and smiled. “If you’d known when you were eighteen, you would’ve spent every summer in Bali and called me crying from a yoga retreat because your aura hurt.”

She groaned. “Fair.”

“Money is only as good as the decisions it buys you,” I said. “I got kicked out. I got told I had cancer. I decided to exchange some of the number for safety and peace. So, yes, I have a pool now. Also nurses.”

She exhaled in the way she does when she’s letting logic braid with love. “And the cancer?”

“Benign,” I said, and you could have heard the phone smile. “They did more scans. The tumor’s not cancerous. They’re monitoring it. It’s the kind of drama that gets written out in the second season for lack of audience interest.”

“Mom,” Scarlet said, and I heard as much forgiveness as laughter.

That night Daniel called.

“Hey, you,” he said, as if he had forgotten the week between us. “Scarlet tells me you’re in some kind of—what did she call it—glamorous care castle?”

“She called it that?” I asked, because sometimes our daughter says things that make the inside of my head a carnival.

“Well, she said the view is amazing. Pool. Nurses. How—?” He cleared his throat. “Why would you be living there?”

“Because I can afford to,” I said. “Inheritance from my father. I put it in stocks. Ten million dollars, give or take.”

There is a particular kind of silence that contains a man’s mental arithmetic. Then: “Ten million,” he said, the words almost affectionate. “Then we should divide it. Half is fine with me.”

“Oh, Daniel,” I said, genuinely. “Inheritance isn’t marital property. And what it becomes isn’t, either. Also, I haven’t claimed a cent of your assets. You gave me a bankbook with three thousand dollars in it and a list of instructions you thought were orders.”

“Well,” he said, faltering, “I’m not married yet. I could—maybe we rushed. Maybe we should—if you’re sick, you shouldn’t be alone. We could remarry. For your peace of mind.”

“I’m not worried,” I said, and kept my voice light because he would hear the truth of it and it would crush him more kindly than anger. “The scans came back. Benign. Nurses on call. A pool that makes me forgive the word ‘amenities.’ Please marry your girlfriend before she realizes you have a drawer full of socks you’ve owned since Clinton.”

He laughed, small. “What happens when you die, then? It goes to the government?”

“Scarlet inherits,” I said. “The government can get the taxes it deserves and not a penny more.”

“That’s too much money for one person,” he snapped. “It ruins people.”

“The money isn’t yours,” I said. “So you don’t need to worry about what it ruins.”

“You should leave it to me,” he tried. “I’m responsible enough to keep it safe.”

“You left me when you thought I had cancer,” I said. “You are not a reliable vault.”

It would have been enough to hang up. It would have been enough to take my ten million dollars of peace and float on it. But fairness demands edges sometimes. And fury, when it takes its vitamins and stretches, can be extraordinarily productive.

I called a private investigator.

The report felt like a novel written by a man who had forgotten he was supposed to be nonfiction. Diabetes, it said. Poorly managed. Rarely takes meds. Recently limping. Full dentures. Complication risk high. House: thirty years old, prefab, leaks, cracked walls, sloping floors. Girlfriend identified as Hannah Ross, thirty, nightlife worker, substantial debts, shopping addiction, habit of aiming for men whose pensions are about to fatten.

I read it all and laughed into my tea. Not because suffering is funny. Because fate’s sense of timing is meticulous and deeply rude.

I called Hannah and asked her to meet me at a café near the station. I arrived as the kind of woman I have always been underneath the marriage—a woman who likes matching her handbag to her ring and wearing shoes that make a sound even carpet respects. Hannah arrived like a magazine ad with a human story stapled to the back.

“You’re his ex-wife,” she said before the waiter could put down the water. “I’m not giving him back. And I’m not paying you alimony.”

“I don’t want your money,” I said. “I want to tell you a few things about Daniel so you can make an informed decision. That’s all.”

She glanced down at the bracelet I’d bought in Florence when I thought Daniel would be alive long enough to share the story with our grandchildren. “Go on,” she said.

“Full dentures,” I began. “He has to take them out after every meal, scrub them, keep an eye on the gums. Otherwise bacteria proliferate. Oral infections can escalate fast. If bacteria enter your bloodstream…” I saw her eyes widen, and I did not enjoy it. I simply watched information adjust her expectations.

“And,” I said, “diabetes. Badly managed. His doctor has been prescribing meds he can’t be bothered to take. Neuropathy causes that draggy gait he has. If he keeps ignoring it, he could face amputation.”

She cursed, quietly and elegantly. “He never told me.”

“Of course he didn’t,” I said. “He’s trying to sell you an image.”

She blinked. “But he has savings.”

“He has a house,” I said. “It’s falling apart. Everything he should have saved is under that ceiling, literally. When he retires, his pension will go into patching it. If he’s not careful—” I shrugged. “You’ll be eating ramen in a room that leaks when it rains.”

She lifted her glass and drank water like it was wine. “And you have ten million dollars,” she said finally. “Lend me one.”

“No,” I said gently, the way you do with a toddler who asks for the moon and thinks your arms are long enough. “I’m not a bank. Nor a fool.”

“Then why did you call me?” she demanded, affronted. “To scare me off?”

“To give you the same courtesy your boyfriend didn’t give me,” I said. “The chance to choose, honestly.”

She left in a rush of perfume and indignation. I paid the bill and went home to my pool.

Three days later Daniel called. He didn’t say hello. “What did you tell her?”

“The truth,” I said. “Did she not like it?”

“There’s no truth like the kind that costs you thirty thousand dollars,” he snarled. “She maxed my card. Cash advances. I’m about to retire. How do you expect me to pay this off?”

“It appears,” I said, “that she expected you to pay it off.”

“Then she left,” he said, and the sentence fell on its face. “She’s gone.”

Silence, the generous kind, filled my end of the line.

“My foot’s worse,” he added, desperation pushing in. “Doctor says surgery or risk necrosis. I don’t have the money.”

“Consumer loans exist,” I said, because I am an encyclopedia of modern injustices even when I don’t want to be.

He took one. He had the surgery. He told me the pain in his leg was the illness’s fault. He told me he needed the sweets because the craving was bigger than he was. He told me he’d go back to work after he healed, and then the complications multiplied, and the job disappeared, and the pension came small and came once, and the debt gathered interest like dandelions gather bees.

“Help me,” he said, in a voice I used to want to wear like a shawl. “You’re the only one I have.”

“You’re a stranger,” I said, and set the phone on the counter as the nurse knocked and asked if I’d like to try the aquatherapy class that starts in ten minutes.

He declared bankruptcy. The message came from a mutual friend who always leads with the weather. I told the friend I was sorry that age was what age is and that some lessons do not care if you are ready to learn them. Then I blocked Daniel’s number.

At my next appointment, the doctor smiled and said that “benign” is the kind of word we need to invent new ways to celebrate. The tumor slept like a well-fed cat. I swam my laps and felt the way my body says thank you with each patient, clever stroke. I made Scarlet promise to bring her swimsuit and learned to love my hair as it is, not as it was in the wedding photos.

For the first time in decades, I woke each morning and didn’t drown in someone else’s definition of my life.

Part Two

People will tell you that the moment you gather enough courage to leave, you will feel clean relief like a breeze through a doorway. People who have never paid a lawyer’s invoice like a tithe forget about the middle.

The middle is where Scarlet calls because she saw Daniel in the grocery store lurching past the tomatoes like a man trying to outrun a metaphor. The middle is when you buy a robe for the spa and a bright sweater and remember you are allergic to orange and return it for a green that makes the whites of your eyes whiter. The middle is the grocery delivery guy who recognizes you from the old neighborhood and doesn’t ask questions. The middle is a handrail on the stairs that feels like your mother’s arm at the bottom of an escalator in a busy mall.

It’s also the private detective’s second report, the one that arrives a month after the first and reads like a coda. Subject appears to have lost employment. Loan activity consistent with predatory interest. Estranged from paramour. Home repairs deferred. Mobility compromised.

I sat on the balcony with the report in my lap and the city sprawled like a patient dog below me. I shouldn’t have felt anything but vindication. Instead I felt the edge of a sadness that is not sadness exactly. It is recognition. I used to love a version of that man. I used to iron his shirts while the news told me the world was complicated and I felt certain there were a few things that weren’t. I used to look at my own hands and think how convenient it was that care had made them strong.

Inside the apartment, Scarlet made me tea and told me I was allowed to feel things out of order. She told me grief is not honest if it does not contain relief. She told me I was not required to change the subject when the subject was my new pool. “Tell me about the spa again,” she said. “I need to live vicariously through the bubbles.”

I told her about the spa. I told her about the small kindness of being handed a towel and not a bill for being a person who needs a towel. I told her about seeing my reflection in the water and not flinching. She came the next day with a swimsuit and we took awful selfies that would make us laugh in a decade.

Then Daniel found a new number and called. His voice was smaller than it had been before the foot surgery. The surgery had gone fine, he said, and then another complication had risen like a newborn gripe. It was all very unfair, he said. The job shouldn’t have let him go when he needed to pay so many debts. Hannah had disappeared, and he couldn’t think why. The house was colder in the winter than he remembered. He wanted to come see the apartment. “We could sit on your balcony,” he said, “and talk like we used to.”

When I hung up that time, I did not block the number. Not yet. I wanted to enter the courtroom of my own brain and deliver the verdict with flourish.

I called him back and didn’t say hello. “Inheritance law,” I said, “exists for a reason. What my father left me is mine. What I made of it is mine. You have your pension, your dignity, and your ring back. I suggest you find a way to solve your problems that doesn’t involve my bank account.”

He started to reply and I cut him off. “Also,” I added, because I am a woman who delights in letting her point land with confetti, “I made a will. Scarlet inherits. If you were thinking of proposing, consider yourself spared the ring shopping. Good luck.”

I ended the call. Then I blocked the number. The number did not fight.

In therapy—because wealthy women owe it to the less wealthy to admit they need help too—I said out loud, “I’m not angry anymore,” and my therapist raised an eyebrow and told me to sit with what it says about me that the sentence made me want to immediately find something to straighten.

Am I angry? Not in the heat sense. Am I a woman with a list? Always.

I had tea with Hannah once more. Not because we are friends. Because I wanted closure, the kind that feels like finishing stitches.

“I returned the man,” she announced, sliding into the booth as if she had been invited to join a conspiracy. “No refunds, though.”

“Returns policy is strict,” I said, and signaled to the waiter that neither of us needed caffeine.

“I never liked dentures,” she said, surprising us both with her own humanity for a moment.

“You will like twenty-nine-year-olds with dental insurance,” I said, and we both laughed, because human beings will always find the ability to make jokes where dignity ends.

When I left her at the café, she looked at me the way women look at each other when the man between them has left the room and the air rearranges itself.

“Do you feel bad?” she asked. “About any of it?”

“About some of it,” I admitted. “Not enough to wish for different outcomes. Enough to wish for fewer bruises on the way to the lesson.”

The courts move slowly when they aren’t trying to ruin you, and I had the luxury of getting bored by justice. Scarlet and I gathered photos for a new album: Life After. The first page is a picture of my hospital bracelet with a line through it that says Benign. The second page is Scarlet in a ridiculous pink bathing cap. The third page is my father sitting on the couch in my new living room, holding up a book he bought at a garage sale in 1978 and insisting we all need to read because “the sentences are hard and we deserve that.”

One afternoon I sat on my balcony and made a list of things I needed to do: change the filters; buy a better kettle; send Scarlet that article about lilies being toxic to cats; ask the building manager the name of the tree in the courtyard that flowers twice a year like an apology. Underneath the list I wrote: Write a letter to future self reminding her that the right thing can feel like arrogance while you’re doing it.

There is an email in my archive I sometimes reread when I feel the old obligations clawing at the beautiful wallpaper of my days. It is from my lawyer, the woman whose voice could rescue a yacht full of fools. “Inheritance is not subject to distribution upon dissolution of marriage,” it says in language that keeps mercy and math from kissing. “Nonmarital property remains nonmarital when invested wisely.”

It’s a boring sentence, and it won my life.

I wish I could tell you Daniel found a new woman who loved him and his dentures and his glucose monitor and that they moved to a small apartment and made soups together and laughed at their own jokes in a living room with plants. It would be a kinder ending. The truth is, he found a recliner that fit the way he sat, a television that distracted as needed, and a bitterness as familiar to me as his cologne. Sometimes he calls Scarlet, and sometimes she picks up, and what they say to each other belongs to them. I have made peace with the fact that not every story needs a villain. Some need a lesson. Some need a distance measured not in miles but in choices.

Last week, I went downstairs for the aquatherapy class with the nurse who wears crocs covered in stickers. A new woman, hair a tuft of carefully rebellious white, stood by the pool looking like she had arrived at the wrong party.

“First time?” I asked.

“My daughter bought me a pass,” she said. “She thinks I’ll like the spa more than I like my recliner.”

“She’s right,” I said, and held out my hand. “I’m Charlotte.”

She took my hand and stepped into the water. We both hissed like cats. Then we laughed.

In the lobby after class, I bought a muffin I didn’t need and sat on a bench I had sat on when my life was a husband’s inventory and not my own treasure. The city was a painting behind glass; I decided I liked the angle.

I went home and wrote a list titled Not a coda. It contained three things:

-

Tell Scarlet she can come swim anytime, even if it’s just to float and stare at the ceiling and name the shapes the plaster makes.

Make an appointment with the estate lawyer to set up a scholarship at the hospital for women who need care and can’t fill out forms that ask for a husband’s signature.

Buy new basil. I can’t keep stealing from the neighbor’s balcony garden. (Apologize. Bring cookies.)

When I closed the notebook, I realized I had accidentally made a happy life. The kind people envy without knowing if they could endure the work it took to build.

Daniel will be fine or he won’t. The mortgage on my past is paid off. The tumor naps. My daughter knows her mother is a person first and an instrument of anyone else’s expectations never again.

And sometimes, in the afternoon, I press the button by the bed just because I can, and a nurse appears and says, “What do you need?” and I say, “Nothing, really,” and then, because wealth is only as good as the kindness it makes easy, I add, “Do you have time to take a muffin? They’re better when they’re still warm.”

END!

News

Husband fumes over stolen $900, demands divorce. I agreed, stopped the allowance. ‘What’s next_’. CH2

Husband fumes over stolen $900, demands divorce. I agreed, stopped the allowance. “What’s next_” Part One “We’re getting a divorce….

My husband: “Your family home? I pay, so I rule!” he sneers, moving his mom in. CH2

My husband: “Your family home? I pay, so I rule!” he sneers, moving his mom in Part One The evening…

My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and… CH2

My MIL said: “Clean the toilet” while we were eating. I slammed the papers on the table and… Part One…

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house. CH2

My husband: “Your opinion doesn’t matter,” as he moved his parents into my house Part One “Did you really think…

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: ‘Move in with My Parents or Divorce!’. CH2

My Husband Gave Me an Ultimatum at My Father’s Funeral: “Move in with My Parents or Divorce!” Part One The…

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything. CH2

My Sister Stole My Wedding and Fiancé While I Was Away, But My Secret Changed Everything Part One The worst…

End of content

No more pages to load