My DIL: “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing!” “This party is not for you!”

Part One

It should have been a night of uncomplicated joy. The banner over the mantel read CONGRATULATIONS, AIDEN! COLUMBIA CLASS OF ’28 in gold letters, one of those glossy sets that looks better in photos than in real life, and the fireplace crackled like someone had googled cozy and made it so. Yet standing in my daughter-in-law’s kitchen, watching a caterer I didn’t know sear scallops in a pan I’d bought my son for his first apartment, I felt like a stranger in a house I’d helped them call home.

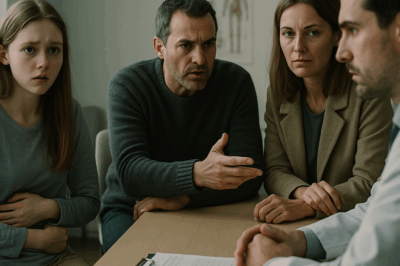

“How could you do this to us?” I heard myself say before I could pull the words back. They came out too small for the long, beautiful room lined with windows. Alan, my husband of thirty years, shifted his weight beside me. He has a way of standing when he’s about to say something calm; he looks like a tree deciding where to put roots.

Clara peered over the dining table the way women on TV do when they’re trying to sell you a dress you can’t afford. “Do what, Meredith?” she asked, blinking her thick lashes. Her voice was high and airless, like the peculiar quality of a room that’s been cleaned too often.

“You didn’t make anything for us,” Alan said quietly. His voice holds more hurt than anger; it is the sound of someone surprised, always, to be disappointed again. “You knew we were coming.”

Clara laughed—the kind of light, tinkling sound that sets teeth on edge if you’ve ever waited tables. “Oh, I just didn’t have the time today. Anyway, we’ll order something later. This party is for Aiden, not you.”

The metallic taste of restraint filled my mouth. Easy, Meredith. Not now, I told myself. I smiled the polite smile women’s magazines teach you to wear when people mistake kindness for currency. “Of course. Whatever Aiden wants.”

Aiden stood by the French doors with his friends, tall the way eighteen happens overnight. He has his father’s gentle eyes and my mother’s smile. He was laughing at something his friend Finn said, and for a second I remembered him at five in a Superman cape jumping off our couch and Ethan—my son—catching him every time because he told Aiden to fly and then he made sure it was safe. Alan and I helped raise that boy. We bought the first bicycle he rode into the fence; we slept in rotating chairs all night when he broke his arm skateboarding so he wouldn’t be alone if he woke. Last month, when the tuition invoice for Columbia came, we drained a third of our retirement for the deposit without telling Ethan because we wanted to be the kind of parents who still made things possible.

Clara was the kind of woman who makes pictures instead.

“Columbia is expensive,” Alan said evenly, his hand finding mine. “Let us know if you need—”

Clara waved a manicured hand as if shooing a fly. “Oh please. Ethan makes plenty.” Her voice dropped, too loud in its softness. “Certainly more than a schoolteacher’s pension and whatever measly salary comes from working at a library.”

The room tipped sideways. “Our jobs are honest,” I said. “Not something to be ashamed of.”

“Who said anything about shame?” she asked, eyes glinting. “Let’s be real, Meredith. Your pennies don’t even make a dent in Columbia’s tuition. Maybe if you’d had more to invest when Ethan was young—”

“Clara,” Ethan said from the island, a line between his brows I know by heart. “That’s quite unfair. Mom and Dad help how they can.”

Clara’s mouth tilted. “Yeah. Buy the kid a computer and call it a day.”

“That laptop was top of the line,” Alan said, proper anger slipping loose now. “We scrimped and saved. Where is it?”

Clara lifted her wrist and checked the diamond face of a watch that costs more than both our cars. “Look, the catering van will be here in five. Are we done?”

“We are,” I said. “For now.”

We kissed Aiden and slipped our coats from the hooks, the way old people leave parties in movies—smiling like they were born graceful. Alan’s sedan moved down Clara and Ethan’s long, perfect driveway under a stand of linden trees that probably cost more than we sent for the plumber last year. In the passenger seat I held my jaw the way you hold a glass when you don’t trust your hands. The laptop was only the first of many gifts over the years, true. But it was the newest, and in a house full of strangers our grandson’s mother had flung our love at the wall and called it decor.

At home I made tea because my grandmother taught me that boiling water turns rage into something drinkable. Later, when I went to rinse the cups, my phone chimed. Aiden had changed his profile picture: his arm slung around a pretty brunette at a coffee shop. In the background sat a sleek laptop—thin, silver, nothing like the bulky gaming machine we had given him last month, the one he had hugged like it was a person. “Alan,” I said, and my voice did a thing that made my husband look up.

“She sold it,” he said when he saw. The words landed like a hammer on something old.

We sat at the table with the profile picture glowing between us like a spiteful moon for a long time without talking. Then Alan pulled out his phone and called our son.

“Dad? Everything okay?” Ethan sounded distracted. Through the line I could hear voices and the pleasant clink of successful people.

“Where’s the computer your mother and I gave Aiden?” Alan asked without preamble.

“What? The laptop?” Ethan’s voice went sideways, muffled. “Babe, what happened to that computer my parents gave Aiden?” he asked someone at his end who didn’t answer. He came back. “Aiden says he hasn’t used it in months. It was slow. Clara bought him an upgrade. Solid-state drive, faster processor. It wasn’t cheap.”

“So our gift wasn’t good enough. Once again,” Alan said, and the sadness in his voice wore a tired man’s clothes.

“You know how Clara is. Always needing the newest and best.” Ethan trailed off. I bit my tongue until I felt blood. Yes. We knew how Clara was.

I told myself I was an old woman to have jealousy prick my chest. Then, over the next week, I watched. Clara’s clothes got newer and her smile looser. When I dropped off groceries she had offered to “Venmo me later,” an unpaid medical bill with a red FINAL NOTICE stamp sat on the hall table beneath a bowl of lemons. Out front a bookie’s warning flapped in the mailbox with the junk mail. When we tried to help, Clara laughed the way people who have never been poor laugh: too loud, too hard. “We’re fine, Meredith. Ethan takes good care of me.” Her eyes slid away.

A plan arrived the way ideas do when you lay awake and stare at the ceiling and wish the dark were lighter: if status is what she loves, let status lead her to us. Use it. Let her greed be the hook she swallows.

We invited her to lunch at the café near the hardware store where the waitress brings you napkins before you ask. I came with a soft delivery and a sharp purpose.

“Aiden’s got such a bright future,” I said over chicken salad. “We want to invest in it. Columbia is expensive.” I kept my tone casual, my eyes warm, everything about me offering. “We don’t mind dipping into our savings if it means he isn’t worrying about money.”

“Nonsense, Meredith,” she said, straightening like a cat that has competed with another for a sunbeam. “He’s our only grandson,” I added purposefully. “We thought a college fund, in his name, for his direct use.” Bite, I thought. Take it.

“Oh gosh, no.” She flashed that glittering smile. “We’d invest it into one of Ethan’s portfolios. For the best return.” She touched my wrist. “Can’t have money just sitting around.” She leaned in, conspiratorial. “It can be our little secret from Ethan. You know how hard it is for dads to let their babies grow up.”

Gotcha, I thought, and something hard in me clicked.

We withdrew the last of our carefully built savings in small transfers so the bank wouldn’t bother us with questions. Each deposit, I wrote Tuition—Aiden in the memo line because superstition is just grief dressed for church. Every time I transferred funds, I reminded her: “Every cent is for Aiden’s education.” Every time, she said, “Of course. Consider it his rainy day fund.”

Still the unpaid notices multiplied. Still she shone in clothes that reflected everything back at you and nothing from within. Clara borrowed from Ethan and then laughed when I caught compassion in my son’s eyes. “We’re fine,” she insisted. And because you can’t tune the mouth of a woman like that when the volume of her friends is set too high, we stopped asking.

The day of Aiden’s eighteenth birthday wore a beautiful sky. The driveway of their modern house was crowded with luxury cars we passed with the quiet pride of people who know how to fix their own engines. A DJ set up behind the pool played songs I pretend to hate when they come on the radio because I am sixty-two and I like Frank Sinatra better for washing dishes. Aiden hugged us hard enough to make my back pop. “You’ve got to see my gifts,” he said, grinning.

We sat on patio chairs that cost more than any chair should and watched a parade of pretty boxes with labels that made other people in the crowd say, “Ohhhhh.” At last Clara clapped her hands. “Ready for the big finale, birthday boy?” she cried, and motioned to the DJ who cut the music. The sleek black BMW coupe rolled up the driveway with a red bow like we were in a Christmas movie and I heard the sentence leave my mouth before I knew I could make it—that old teacher’s tone that still lives in my throat: “We’ll get out of your way.”

Clara slid toward me like a waitress bearing the bill. “At least your gift stack isn’t too shabby this year,” she said, all sugar. “Hope you saved some retirement money for the Rolex he’ll want next year.”

We left.

Back home, I put on my glasses and opened my laptop and logged into the secret account Clara had made me believe would make our grandson’s life easier. The number on the screen was a knife.

Zero is a sound if you listen for it.

“No more,” I said, and Alan held me while I cried the kind of tears you wipe off willfully because you don’t want them to get used to the landscape of your face.

For the next week, I moved through our small house with the methodical calm of a nurse changing dressings after a long surgery. Bank statements, printed. Screenshots, labeled. Medical bills with URGENT in red, photographed. Photos of Clara on beaches when she had texted me that she needed money for groceries, filed. The vendor invoice for a $6800 purse purchased on a day she had told Ethan that the doctor would not see her unless she paid in cash, paper-clipped.

Sometimes you have to show someone who they are for them to remember.

We invited Ethan and Aiden to dinner in our little dining room with the tablecloth I had stitched the year Aiden learned to write his name and bent his pencil in the middle of the O. “Where’s Clara?” I asked when they arrived, though I could guess.

“Appointment,” Ethan said, the way men say I’ve decided not to fight tonight.

We ate beef stew because I believe in food that can hold you up from the inside when you are about to swallow hard truths. We asked about Columbia. We asked about dorms. We did not ask about money because everyone in the room had lungs and I did not want to be the reason theirs forgot how to fill.

At last Ethan pushed his bowl away and exhaled. “Okay,” he said. “We need to talk.” He looked like my boy at fourteen asking if we could fix the dent in his car and tell his father it came that way. “Mom—Dad—Clara asked me to put almost everything into a crypto thing. She said she had a good feeling. The CEO was indicted last week. The assets are frozen. I think it’s all gone.”

“You saved money,” I said, sharper than I meant. I could see Aiden’s eyes flick between us like a metronome.

“For the tuition this year, yes. But the rest—” Ethan’s voice failed him.

I reached under the table and lifted the heavy box onto the oak. Aiden’s gaze sharpened. “What’s that, Grandma?”

“Truth,” I said, and lifted the lid.

I laid each piece slowly, like a dealer turning cards. The final notice slips. The airline receipts. The Facebook photos with the location tags. The transfers into the secret account—Tuition—Aiden—and out again with speed. The bookie notice. The sales receipts for the bicycles we had bought over the years and left in their garage “for Aiden to ride when he visits,” listed on Facebook Marketplace two days later. The gaming laptop, parted out.

Aiden read with his mouth set. He has my son’s stillness when he is properly angry. “Is it true?” he asked at last without looking up. “Mom took it? My college money?”

The front door banged open. “Absolute disaster,” Clara said in the voice of people who have never had one. The Chanel hit you in the face before she did. She stopped when she saw the table.

“What exactly did I interrupt?” she asked, and for half a heartbeat my heart did the thing hearts do when they want to believe in repentance. Then she lifted her chin. “If this is about the tuition, it didn’t work out as planned, but I did it for us.”

“For us?” Aiden’s voice cracked around the words. “By stealing my college fund?”

“Stealing?” She laughed that glass laugh. “Don’t be dramatic. It was an investment. We could have had everything.”

“We wanted to pay for a semester,” I said. “You sold his future.”

Ethan rubbed his face with both hands like he wanted to erase the last year. “Did you sell the laptop too?” he asked quietly.

Clara looked at Aiden, then at me, then at the papers. “You people are obsessed with minor details.”

Aiden stood, the chair skidding back. He is a good boy. He did not swear. “You sold my birthday gifts. You lied. You always lie,” he said, and something like relief crossed his face like anger had finally handed him a useful tool. “I’m done.”

Our son started divorce proceedings the next week. The papers arrived at Clara’s hand while she was posting a photo of herself in St. Barts with a caption about healing. She called me that snake on Instagram and three of her friends unfollowed her because divorce is contagious in certain zip codes.

Between a small scholarship, a school grant, a reasonable loan, and the money Alan and I dug up by selling his coin collection and my wedding china because I fell out of love with plates the year Clara registered for twelve soup tureens, Columbia stayed in reach. In a quieter house, Aiden started laughing again the way boys laugh who have had to hold it together for their mothers too long. He learned to fry an egg without oil popping his arm. He asked his grandfather to teach him how to change a tire. He called me on a Tuesday to ask how long to cook chicken thighs and I said, “Until it smells like home.”

At the end of August the air smelled like possibility and hot tarmac. In the long-term parking lot at JFK, I cupped Aiden’s face in my palms and remembered the way I used to hold his head under water when we rinsed shampoo out and tell him to keep his eyes shut. “I am so proud of you,” I said. “One day you’ll pay this forward.”

“I will,” he said, his chest expanding on the inhale the way baby birds do before flight. “Thanks for everything, Grandma.”

We watched him walk through the sliding doors with a duffel bag and dreams and a spine that had learned how to bend without breaking. I went home and sat on the porch with a glass of lemonade, because sometimes you must perform contentment until it decides to live in your house. A yellow leaf fell from our maple onto the railing like punctuation.

I thought about Clara and the sentence she had written on my life for years: not enough. I thought about the way she had said, “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing.” I thought about her laughing, “This party is not for you,” and the way I had gone home and quietly built one. The music was different and the food was plainer and the guest list was short. We called our party Consequences, and the only people invited were the ones who understood that love is proof of value and money is not.

Part Two

You never think about escrow until the absence of money becomes a character in your life. After Ethan moved out, the mortgage notice turned red and Clara did what people like her always do: she sold the story, then the furniture. When no one bought, she posted a photo of herself with mascara running and a caption that cast Aiden and me as villains and begged the Internet to pick a side. The comments were kind for a day and then bored. Drama fatigue is real, even among people who consume it like popcorn.

We did not gloat. We went to our jobs. Alan repaired a shelf the teenagers at the library had found with their feet. I shelved biographies because it comforts me to put people’s lives in alphabetical order when mine won’t comply.

The first week of classes, Aiden sent a photo of the library for the physics building: stained glass and old wood and desks carved by boys who were now dentists. He sent a picture of his dorm room with sheets I had bought with a coupon and a thrift-store rug that looked like someone had made a mistake and then committed to it and it turned out well. He wrote, I love it here. Everyone is weird in the best way. I printed the email and stuck it on the fridge with a magnet shaped like a strawberry. Clara would hate the fridge, the email, the magnet. Some joys are born petty.

Clara’s world shrank the way worlds do when money runs out of air. Her favorite boutique did not offer complimentary champagne anymore. Her salon moved her from our chair to a chair by the window so passersby could see that even beautiful women need roots retouched. She posted a quote about quiet strength under a photo of a handbag that cost a semester of books and three of her friends wrote, You got this, babe. She believed them until the credit card company called. I know this because Ethan told me when he dropped Aiden’s class schedule on our kitchen table and drank coffee he made too strong. “She doesn’t know how to scrape,” he said, his voice both sad and certain. “She calls it whining when other people do it.”

When the crypto case hit the news, I did not smile. If I learned anything in the last year, it’s that other people’s losses are not your lessons to deliver. But when Aiden’s loan office called to say a small error had become a grant because of paperwork I had filled out correctly, I allowed myself to dance in the pantry. It was the kind of dance where no one should see you. It looked like happiness, awkward and plain.

Two months into the semester, an envelope with the college seal arrived. Aiden had been selected as a peer mentor for first-year students from low-income households because he had written an essay where he argued that the difference between poor and rich kids is not hunger; it’s the grace they’re allowed to extend to themselves when they fail. The stipend would cover his meal plan. I taped his essay under the magnet next to the email because refrigerators, in their way, are altars.

I did not hear from Clara until Thanksgiving week. She sent a text message that began: We are family. It continued with a request for Aiden to come to dinner because holidays matter and ended with a threat: He’ll regret it if he chooses you over me. I showed the text to Ethan and he laughed the laugh you make when you finally understand that manipulation is a form of weather and you learned how to buy an umbrella too late. “We’re going to your mother’s,” he told his son. “Bring friends.”

We roasted two turkeys because I have never learned how to feed anyone small. Our dining table held the weight of too much gratitude easily. Aiden carved with cautious pride. He kissed my cheek and whispered, “Thank you for not giving up,” and I told him, “That is the job description,” and he said, “It wasn’t always yours,” and we both pretended to eat cranberry sauce while we swallowed something more important.

The day after Thanksgiving, Clara posted a story from a hotel two hours away with a caption about gratitude. In the background of one frame you could see a loan document on the bedside table. I enlarged it and realized that the hotel bedspread was the one I had chosen when I had booked that hotel for Alan and myself for our seventh anniversary and we had gotten snowed in and ate onion rings in bed. When I told Alan, he didn’t laugh. He said, “You can’t hate someone honestly until you have tried to understand why they think drowning looks like floating.”

That winter, the college sent Aiden to a conference on student leadership in Chicago. He took a photo of the Bean and another of himself with a girl in a hat that made my fingers itch to fix and I texted him, Wear a scarf. He wrote back, I did. He sent a screenshot of a message from a boy on his floor: I’ve never been to a museum; wanna go? and a photo of the two of them in front of a painting of a woman and child that made me think of myself and my mother and a thousand women in kitchens who never took their aprons off their hearts. I cried in the laundry room folding a towel that had been clean before I needed to be alone for two minutes.

Clara filed a response to the divorce petition with accusations that read like those movies where women watch themselves be villainized and wonder whether the world is worth the trouble. Ethan’s lawyer countered with a list of facts and a repose that would make my mother’s church friends clutch pearls they had not paid for. When the judge parceled out what can be parceled in rooms like that, Clara received exactly what consequence promised: a small stipend and the knowledge that a boy who used to be a mirror had finally become a window.

In March, an envelope arrived at the Second Voice office with no return address and glitter around the flap like a trap. Inside was a letter on thick paper that smelled faintly of perfume. I never wanted to hurt anyone, it began, and then did not apologize. It was signed C. I threw it away because there are sentences you do not lift to your eyes if you want to keep your vision.

Spring arrived the way hope does—slowly, with a mess of false starts. Aiden came home in May with a cheap blender and a top hat he had used in a student theatre show and a request for my potato salad because sometimes survival looks like a festival of small pleasures. He stood by the sink washing dishes without being asked and said, “Mom texted me. She asked if I wanted to take a trip to Europe this summer.” He looked like a boy and a man at once. “I told her I have an internship in New York and that plane tickets are not therapy.”

“What did she say?” I asked, kneading dough the way my grandmother taught me to make bread on days when not throwing a knife looked like maturity.

“She sent a photo of the Eiffel Tower,” he said. He laughed—soft, almost sorry. “With a heart emoji.”

The day he left for his internship, Alan and I took him to the airport at dawn because we are people who do things like that. At the kiss-and-fly lane, he hugged me long enough that the cop in the yellow vest walked around the back of the car instead of knocking on the window. “Pay it forward,” I told him. “Get the girl from down the hall a job when her father won’t write her a recommendation. Let your roommate talk about his mother for five minutes and then say, you didn’t deserve that. Refill the paper in the printer and don’t tell anyone.”

He smiled. “I learned from the best.”

I watched the doors swallow him and knew, in the way stubborn women finally let themselves know, that Clara had not won what mattered. She had won photos. She had won nights with people who would not help her move when the apartment manager put an eviction notice on her door. She had won laughs that stopped the moment hers did. She had lost a family she could have had and a future that did not require a red bow to look stunning.

At home, the maple out front had leafed into the kind of green that makes you forget being told it would not grow back. I sat on the front steps with a cup of tea and wished Clara enough humility to become worthy of her own son’s forgiveness one day, not because he owes it, but because people who teach themselves to be sorry sometimes become better grandparents. Then I stood up and went inside to the table where bills meet envelopes and folded a check for the scholarships fund the library runs for first-generation college students. In the memo line I wrote, Because sometimes pennies are the point.

On a wall in our hallway there is a photo of Aiden at five in a cape. Next to it, a recent one of him under old library windows in a city that still knows how to hold up dreamers. Between them hangs nothing, and that empty space is my favorite part. It is proof that pauses matter just as much as pronouncements. It is the place I keep for breathing before the next sentence begins.

A month later, Alan and I drove to the shelter downtown to drop off books. As we unloaded the trunk a volunteer asked if we could use a hand. It was Clara. She looked tired. Not ruined—older. She handed me a box and said, “I’m trying,” and my mouth didn’t say good. It said, “Thank you for the lift.” Because if consequence taught me anything, it’s that building is contagious. It’s that parties thrown for the right reasons are tender, and nobody laughs when the cake is small.

I went home and baked two loaves of bread because I like watching yeast do what it’s told. I wrapped one in a tea towel and set it on my son’s stoop. I sliced the other and sat on the porch while the neighborhood’s evening reminded me of summer at ten—sprinklers, grill smoke, someone calling, “In five minutes!” to a kid who pretends not to hear.

Clara’s voice lives in my head still sometimes. “This party is not for you,” she had said. She was right. She threw a glittering thing that was not ours. We built a steadier one with paper plates and potato salad and a guest list of people who know the words to happy birthday without checking the key. She had told me, “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing.” I spent those pennies. I broke them into nickels and dimes and handed them to boys who needed bus fare and girls who needed binders. I learned that in the right hands, pennies can move mountains.

That is what revenge looks like when you have lived long enough to recognize the value of quiet: not the sound of someone else falling, but the noise a family makes when it learns to stand.

END!

News

My Dad Smashed My Jaw for Talking Back Mom Laughed Now You’ll Learn To keep That Gutter Mouth Shut. CH2

My Dad Smashed My Jaw for Talking Back—Mom Laughed, “Now You’ll Learn To Keep That Gutter Mouth Shut” Part One…

My Brother Smashed My Laptop a Week Before My Final Thesis Was Due — My Parents Laughed… CH2

My Brother Smashed My Laptop a Week Before My Final Thesis Was Due — My Parents Laughed… Part One A…

My Dad Beat Me At My Engagement For Refusing To Give My Brother My $100,000 Wedding Fund. CH2

My Dad Beat Me At My Engagement For Refusing To Give My Brother My $100,000 Wedding Fund Part One The…

My Dad Smashed My Laptop On My Head Before Final Thesis Said “Leech You Don’t Deserve Future”. CH2

My Dad Smashed My Laptop On My Head Before Final Thesis—Said “Leech, You Don’t Deserve a Future” Part One My…

My Sister Broke My Rib in a Fight — My Mom Laughed “Don’t Call the Cops, It’ll Ruin Her Life. CH2

My Sister Broke My Rib in a Fight — My Mom Laughed “Don’t Call the Cops, It’ll Ruin Her Life”…

At the Hospital, My Parents Asked the Doctor, “Can We Swap Her Organ to Save My Son Instead?” CH2

At the Hospital, My Parents Asked the Doctor, “Can We Swap Her Organ to Save My Son Instead?” Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load