My Daughter’s Husband Said I Couldn’t Stay For The Holidays—He Needed A Co-Signer For Their Loan

Part One

I remember the moment the holidays changed their meaning forever.

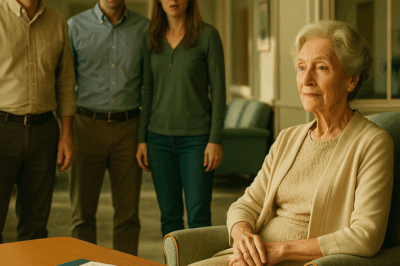

It wasn’t at a funeral or an empty chair at a dinner table. It was in my daughter’s immaculate kitchen—counters scrubbed to a polite shine, oranges lined like soldiers in a bowl—while my son-in-law Brandon shifted his weight, folded his smile around carefully chosen words, and told me they’d “made other arrangements” for the season.

“We just…need our space this year,” he said, hands spread as though he were giving a TED Talk on boundaries. “The kids are at a delicate age. Too much stimulation isn’t good for them.”

My suitcase sat by the door, streaked with salt from the six-hour drive down from Maine. In the trunk of my car: cranberry relish in mason jars, pumpkin cheesecake tucked into a cooler, and a box of ornaments my grandchildren had made with popsicle sticks and glitter three years ago. I had pictured hanging them with small eager hands. I had not pictured standing there, told with that exquisite urbanity that I wasn’t invited.

Olivia—my Olivia—washed her already clean coffee cup. She didn’t meet my eyes. The silence in the room was new and rigid and very old all at once.

I kissed my grandchildren goodbye. I promised to call Christmas morning. I walked into a hotel lobby that smelled faintly of citrus and sorrow and checked in for the first holiday alone in thirty-eight years.

Three weeks later, Brandon called with a voice tuned to a warmer register. Their dream house, he said—3.2 million, lakefront—required a quick offer. They needed a co-signer with “more substantial assets.” He said it lightly, like he was asking me to bring paper napkins to a party.

Funny, I thought, how quickly “we need space” becomes “we need your signature” when there’s a Tudor with heated floors on the line.

I hadn’t imagined starting over at sixty-two. Robert and I had mapped the gentle slope of our retirement—travels we’d take, the treehouse he’d build for grandchildren we’d see every weekend, my classroom packed up with ceremony after thirty-five years teaching special education. But life is less a map and more a shoreline; the shape looks clear from the air until you walk it and discover the hidden inlets and treacherous rocks.

Robert had been the steady one, a financial adviser who shepherded other people’s money with a tenderness he also brought to our marriage. I loved my work and my small rebellions: a pair of bright red boots when everyone else wore sensible brown, a classroom reading corner that even fifth graders snuck back to visit. Our daughter Olivia arrived exactly nine months after our wedding. She was born reaching.

When she was three she’d press a chubby finger against glossy magazine pages—porticos, sweeping staircases, lawns that required maps—and say, with no more drama than observation, “I’m going to live there.” Robert and I would share looks over her head, part pride, part concern. Ambition is a hunger you have to teach to eat politely.

We saved for Olivia’s future the way religious people save their souls: habitually, reverently, even when it was difficult. Robert’s practice grew. My salary stayed modest but steady. We traded a two-bedroom ranch for a larger home in a better district. We sent Olivia to Dartmouth with no loans because we had believed in delayed gratification when the delay made us ache.

Brandon came into our lives her senior year, handsome and self-possessed in a way twenty-two-year-old boys aren’t built for. He possessed the vestiges of “old money” that had been mismanaged by ancestors who loved yachts more than accountants. He admired Robert with a polite avidity that should have warned me; he treated me like a quaint footnote to the story of his own brilliance. “He’s just nervous,” Olivia said. “He wants Dad to respect him.”

What I saw was someone who collected people. For a long time, I thought of myself as immune to being collected. That is the sort of immunity you test only once.

We helped with the down payment on their colonial in Riverdale Heights—one hundred and fifty thousand dollars that represented almost half our retirement cushion. Robert called it “an investment in proximity,” which was his way of saying he wanted to be close enough to drop off soup when Olivia caught the flu or pick up a grandson from soccer practice on a Tuesday without needing to sleep in a hotel.

Max arrived first, equal parts solemn and curious. Three years later Sophie burst into the world with a laugh. I took leaves from my classroom to help. Brandon had crucial meetings precisely when Olivia needed someone to rock a screaming newborn at three in the morning; I learned the rhythm of their dishwasher, stocked their freezer with casseroles, taught Max how to cross-stitch because he noticed Sophie holding a needle and didn’t want to be left out.

Robert got sick. We learned to speak about cholesterol and ejection fractions. He reduced his hours. I reduced mine more. He still made jokes that made me roll my eyes. He still insisted on wearing the tie our grandson picked out even if it clashed like frankincense and fish. He went fishing one afternoon and didn’t come back.

Grief rearranges the furniture in your mind. You keep bumping your shins into memories you forgot you’d left around. The day after the funeral, our family attorney, Thomas Chen, slid papers across the table and I signed where he pointed. I trusted the math because I couldn’t trust my own breath.

When the fog of those first months started thinning, I thought, I can’t be here. Not in this house where every doorway held Robert’s silhouette. Olivia and the children were six hours away. I sold the house with the big maple in front. I put my grandmother’s china into storage and wrapped the wedding album in tissue paper and told myself that proximity to my grandchildren would make a different kind of home possible.

I rented a furnished apartment near Olivia to test the water before buying. For one sweet week, I picked up the kids after school and we set the table together and Olivia called midday to ask if I could grab milk and bread. Then, as the holidays approached, Brandon announced their Thanksgiving would be at the Whitleys, “very intimate, very exclusive.” When I placed cranberries in their refrigerator, Olivia bit her lip and told me not to bother. “They have children your age,” Brandon said, as if that were the point, as if “child” were interchangeable with “grandchild.”

On the driveway, Max asked if I was making cheesecake. “Not today,” I said, and wanted to bite the tongue that made my voice so gentle.

I ate the cranberry relish alone in a rental apartment that smelled unfamiliar even after I filled it with cinnamon. I volunteered at the shelter to hand out plates and found that the only thing that made my hands stop shaking was making sure other people’s didn’t. Olivia called late that night, a little slurred with wine, and said she wished I had been there. Brandon called three weeks later and said if I’d come to the house tomorrow morning we could discuss an important family opportunity.

The Grayson estate is a house that glittered in Riverdale lore: seven bedrooms on three acres of lakefront, a kitchen that needed two ovens not because anyone was using two ovens but because people who paid for houses like that expected to be told they had two ovens. Brandon laid glossy photos on the table. “We need to make an offer by noon,” he said. “The Cutlers and the Williamsons are ready to move.”

“Our preapproval is fine,” Olivia added, “but the bank wants additional security to accelerate the process.”

“Meaning?” I asked, though I already knew; teachers ask obvious questions to see whether kids can speak their own truths.

“A co-signer with substantial assets.” Brandon smiled as if he were offering me a bite of an expensive dessert.

I thought of Robert walking to the mailbox with a hand pressed to his ribs and telling me, “The thing about a storm is you ought to tie down what you can and not build a gazebo.” I did not tie my finances to a man who had banished me from his Thanksgiving table. “No,” I said. “Not because I can’t. Because I will not enable you to build a life your income cannot maintain.”

The mask slipped. It always does if you look long enough. He talked about opportunities and community and the value of an address as if a zip code were a sacrament. He blamed me for refusing to bankroll Olivia’s future because he could not see a future that wasn’t spelled in marble. He threatened access to my grandchildren in a tone so polite I almost missed it.

I walked out. Then I called James Whitaker, my husband’s old business partner, the man Robert used to speak to in a tone he reserved for people he trusted with his life. “He knew they’d come,” James said. “Robert spent hours with me before he died making sure you’d have options when this moment arrived.” It turned out my husband had constructed a trust that matured nine months after his death—not to make me rich, but to make me free.

Freedom doesn’t feel like fireworks. It feels like being able to peel an orange in your own kitchen without someone asking if the peel will make a mess. It feels like walking through a condo with high ceilings and a view of a public park and thinking, this is mine because I choose it. It feels like telling your son-in-law, with dignity but not heat, “No thank you,” and not flinching when his mother shows up to tell you, with a smile that has never reached her eyes, that family resources should benefit the entire family and your place is to make them available.

When Olivia called the next day and said she was bringing the children to my apartment with cookies, I set out napkins that matched nothing in particular and found my grandmother’s teacups just to remember that someone had considered sipping a ceremony once. “Daddy said you were too busy for our family,” Sophie said. “Daddy was wrong,” I answered. “Grandma is never too busy for you.”

Olivia stood in my kitchen with her shoulders high and confessed that school invoices had been opened two days late and returned unpaid, that credit cards she thought were under control were not, that Brandon’s riverfront project wasn’t a river and wasn’t fronting much of anything at all. “I need to see everything,” she said, and in that sentence I recognized the woman I had raised. “Bank statements. Mortgages. The works. If he won’t show me, I will find them.”

The next week she did. The week after that, Brandon filed an emergency petition to recalibrate the children’s visitation in a way that looked suspiciously like leverage. A judge denied it with language that sounded like a teacher telling a smug boy to sit down. Brandon attempted to challenge the trust Robert had arranged. He failed there, too; Robert had always known the value of a well-worded sentence.

In Diane Parker’s living room, they blamed me for setting a match to their aspirations. In my condominium, Diane sat on my chair and told me family comes with obligations as if I had not been meeting them continually while her son sharpened his. I poured her coffee and listened to a definition of opportunity that would have made my grandmother snort. “The right address,” Diane said, “helps open doors.”

“So does the right character,” I said.

We built educational trusts for my grandchildren that could not be siphoned or converted into marble countertops. We wrote clauses that said tuition could be paid, yes, and a violin purchased, yes, and a semester abroad funded, yes, and nobody could touch it except a trustee who did not share a last name with Parker. Diane learned the numbers she could not control and suddenly preferred tea.

Olivia prepared for legal separation with a spreadsheet more precise than any budget she had ever been allowed to see. She discovered, in tallies of debt and interest, a courage she did not know she had been accruing. Brandon threw his coat on chairs and slammed doors into sentences while she sat on the stairs and told him, simply and repeatedly, “No more.”

In March, I closed on the condominium that had seemed a fantasy and turned out to be a blueprint. Two rooms for grandchildren to quarrel over, a kitchen that understood casseroles and cocktails, a balcony where I could watch birds and pretend they were messages from Robert, who believed in two things: compounding and faith. I did not tell Olivia about the trust because it was not my money that needed to be central to our family, it was our values. She didn’t ask again. Instead she came over with paint chips and a measuring tape and the children’s insistence that bunk beds should be pirate ships.

On a Tuesday that held rain like a child holds marbles, Brandon called to say dinner would be served at seven “to clear the air.” The house smelled like rosemary and strategy. He poured wine like an apology and erected a second fantasy: West Lake Shores, premier lots held by a Harvard classmate whose name certainty wore like a crown. “This is about the children,” he said. “Think of the schools.”

“I have,” I said. “I think they’re learning how adults behave. And they need a different curriculum.”

When I stood to leave, he said, “Don’t come back here expecting things to be the same.”

“Things,” I said, “have never been the same since you decided family was a bank with flexible hours.”

At home, I wrote down everything he had said because Thomas Chen told me to keep records and because writing is how I win when I cannot punch. Olivia called the next morning. “I told him I want legal separation unless he can show me every account. He laughed. I called a financial adviser anyway.” The call ended with a plan: Jack and Sophie could sleep in their pirate ship and treehouse rooms that weekend while Olivia packed a bag with too many socks and slept on my couch because sometimes the bravest thing is not to leave, but to stay away.

The next day Diane knocked on my door and arranged herself in my living room like a magazine photograph about how people with money sit. “Family resources,” she said, “benefit the entire family.”

“Yes,” I said, “which is why my grandchildren will be able to attend whatever school their hearts choose.” She opened her mouth and I shut the door.

Olivia looked smaller than she had at twelve when she told me she didn’t want to leave a birthday party early because she was afraid of missing the cake. “I think I made a terrible mistake,” she said. “Marrying a man who believes you make money by spending what you don’t have so people will assume you have it.”

“Endings are corrections,” I said. “Sometimes the only way to edit a sentence is to remove a clause.”

She spent the weekend on my couch between the two rooms she had helped paint. On Sunday she told Brandon the separation papers were ready. He filed an emergency petition twenty minutes later. Family law moves faster than we think when people are trying very hard to hurt each other. The judge wrote an order that had the curve of mercy and the iron of admonition. Brandon’s lawyer called Thomas to say the riverfront project had indeed failed and maybe we could all think of the children.

We do, Thomas said. First, and always.

James, who had known Robert for half his life, called to say Diane had called him to ask whether there were “overlooked resources.” He told her no because there were not. Diane showed up again with a smile so tight it could have cracked stone, and we did not drink coffee. We talked about educational trusts and trustees with names that did not rhyme with her son’s. She signed the appropriate papers because people who care about appearances care about not appearing in court.

By July, the legal separation was in place. Brandon had a schedule. Olivia had access to accounts and a spine. The children had backpacks packed for both houses and learned that sometimes stability looks like a calendar that someone else refuses to disrupt. On paper, it was clean. In hearts, it will take time. That is how hearts work.

On a blue September evening, Olivia sat on my balcony sipping tea because she said wine was a story and tea was a pause. “You didn’t rescue me with money,” she said. “Thank you for that.”

“I couldn’t have even if I had wanted to,” I said, which was both true and not. “Rescue is a muscle people forget they have when someone else carries them.”

“I learned,” she said, “that the opposite of a mansion is not a small house. It’s honesty.”

Jack built a salt-delivery robot with his science club and declared it a success because it made everyone’s soup taste better. Sophie painted trees until she could see them when she closed her eyes. Ellie came to dinner on Tuesdays and told us about the antiques I never saw as a child because I thought they were too breakable to belong to me.

Brandon called sometimes. He learned to say please when he asked me to exchange days and thank you when I did. He stopped saying “opportunity” as if it were a moral virtue and started saying “job” like he meant to go to one. He apologized again once from a distance far enough to make the words less dangerous. Olivia told him she wanted a divorce and then told me she wanted to learn what her middle name was underneath all the noise. I told her it was Grace because that is what I had given her and she had given back to me.

The first Christmas in my condominium, we ate cinnamon rolls at my table and opened stockings with things tucked inside that were not expensive but were chosen. Ellie raised a glass to “Boundaries, that brave little word,” and Peter said, “To checks and balances, in law and in love.” The children sprinted down the hallway hollering about a Lego set that required an engineering degree and I sat down without worrying whether I had earned my seat. That is the true wealth I inherited: the right to be in the room I set.

In January, a woman from a local magazine asked to interview me about the online store I helped build for Green Antiques. She called me a “curator of memory.” I had been a teacher of children for so long; it was startling to be given a name that made what I had done for myself sound like a job.

Sometimes I think back to Brandon’s well-rehearsed smile and the way he said “we need space” as if it were compassion and not strategy. Sometimes I think of the text three weeks later about a house by the lake. A year can be a long time if you are measuring change by the width of a bank account, and terribly short if you are measuring change by the circumference of a heart.

What I know now is this: saying no is an inheritance you give yourself when other people expect you to sign your life away. Love is not a house you are allowed to visit at holidays. Family is not a ledger. The right address is wherever you are allowed to be fully present without paying rent in apology.

Part Two

Brandon and Diane did not stop being themselves simply because a judge told them to slow down. They learned new tactics. Brandon turned contrite when anger failed. Diane turned pragmatic when piety didn’t work. They stopped trying to make me the keeper of their ambitions and focused on the one person whose resistance mattered most: Olivia.

They made her small. She grew big.

If you have never watched your child relearn herself in public, understand that it is a choreography of heartbreak and awe. Olivia found her spine in bank statements and in the way Sophie joined her in the grocery store line and asked to buy off-brand cereal like it was a game. She moved from townhouse to apartment to a small rental with light and learned that “home” was not square footage but permission to breathe. She returned clothes she couldn’t afford and bought a couch that was hers without a signature from someone else. She had dinner with me twice a week and told me uncomfortable truths that were not compliments and we learned to be women together.

Brandon tried to reassert control by threatening to contest Robert’s trust. James and Thomas handled the law. I handled the living. Diane visited in her good clothes and learned to say “educational trust” with her mouth like it was her idea. Between the three of us—two lawyers and a woman with nothing left to lose—the money stayed where it belonged: not as a bribe to a son-in-law, not as bait for a daughter, but as ballast for two children who had done nothing but grow.

Max and Sophie learned to pack bags without resentment. They learned that adults can be angry and still show up. They learned that Grandma’s door is always open and her tea has sugar when their mother says no because love sometimes looks like bending and discipline sometimes looks like not bending and wisdom is knowing which is needed.

One March afternoon, an email from the Riverdale School district pinged. “We’re delighted to offer Sophie a place in the Arts Academy program.” I watched Olivia read it out loud twice, both times with the same catch in her throat. She looked up at me like a girl again and like a mother now and said, “This is what opportunity looks like when it’s not mortgaged.”

Max got into a summer science camp that made him tell me the word “spectrometer” five different ways and then correct me gently when I mispronounced it. “It’s okay, Grandma,” he said. “You know other things.”

Brandon sent texts like weather reports. “Running late. Can I switch weekends?” “Investor dinner. Can you pick up Max at robotics?” Sometimes I said yes. Sometimes I said no. I stopped explaining.

One night in June, Olivia sat at my table with color swatches fanned out like a magician’s cards. “I think I want to go back to school,” she said. “Not for status. For skill. Interior design. Not because of a zip code. Because I want to learn how to make spaces that don’t lie.”

I told her the story of her grandmother painting a wall in the shop apple green because a customer kept talking about needing something fresh and then buying a desk because it looked alive in that light. “Spaces teach us how to be,” Ellie says. Olivia applied to a program and got in. Brandon tried to belittle it. He failed. He used the word “hobby” and then sat in a quiet kitchen because no one answered him.

The summer the children turned eleven and eight, they spent a week with me at the condominium while Olivia took an intensive course. We made grilled cheese every night. We watched movies from my childhood and theirs until we were full of three different decades. They asked questions about their grandfather and I told them the true stories and none of the sad ones, which is also a kind of truth if you are careful with it.

In August, Olivia filed for divorce. It was not messy on paper because she had been careful to make it messy earlier in a way that saved it from being catastrophic later. Brandon’s lawyer used words like “equitable” and “contribution” and “good faith.” Thomas used words like “documentation” and “custodial stability” and “pattern.” Diane stayed out of it in public and probably made calls in private. In the end, the judge wrote a decision that read like a teacher explaining consequences to a student who had been clever and cruel and thought clever canceled cruel.

After, Olivia and I walked out of the courthouse into sunlight we had not expected. She leaned against the brick wall and didn’t cry and didn’t laugh and just breathed for a while. “I thought I would feel triumphant,” she said. “I feel…quiet.”

“Quiet is a triumph,” I said. “Noise is expensive.”

We hosted Christmas again the next year. Not at the lake house with its formal chairs and family drama, but in my condominium with borrowed folding chairs and a turkey that almost didn’t fit in my oven. Ellie sat at the head of a table that bent under casseroles and joy. Peter carved, because in our family carving is not a gendered assignment but a skill, like negotiating or making pies. We toasted to what we had learned: Olivia to transparency, me to saying no, Ellie to always reading the fine print, Peter to finding the good pepper grinder.

After dinner, the doorbell rang. It was Brandon, holding a small wrapped box and looking like a man who had practiced a speech and lost it somewhere on the stairs. “I wanted to drop this off for the kids,” he said, and then looked at me and added, “and for you.” He handed me a package that turned out to be a photograph of Robert, taken at a family event when we weren’t looking. He is laughing, unscripted. I touched the glass and said, “Thank you.”

“I am trying,” he said. “It is not always pretty.”

“I can tell,” I said, and meant it, both the trying and the not pretty. He left without putting on a performance. If that is not progress, then perhaps there is no such thing.

Mandy and I are…something. Not what we were when we were girls sneaking cookie dough and making forts. Not nothing. We exchange cards sometimes. She sent me a photo of toddlers with paint on their fingers and a caption that said, “Volunteering on Tuesdays. It helps. I’m learning to ask kids questions and not give them answers.” I sent her a picture of Sophie’s painting that won a prize and one of Max and his spectrometer and did not add any moral to the stories because she needed to write her own. Sometimes I see her car in town and we wave like neighbors who are not ready to be friends.

Ellie turned eighty and announced she would be downgrading from two announcements a year to one because “even justice gets tired.” She gave me a ring that had belonged to her grandmother and told me, “Wear it or sell it, but don’t put it in a drawer.” Sometimes I wear it and think about the line of women who did not sign their names because nobody asked them to and the line of us who learned to insist.

If there’s a moral, it lives in the space between two sentences. The first one is the one Brandon said about space when he wanted me out of his kitchen. The second is the one I say when I pour tea for my grandchildren and tell them stories that are true: Space can be a dismissal. It can also be a gift. It depends on who keeps the key.

Brandon told me I couldn’t stay for the holidays. He taught me how to spend Christmas alone. Then he taught me how not to do it again.

When he needed a co-signer, he discovered something he hadn’t expected: the woman he thought was a liability had been saving like a lesson plan for exactly this day. I didn’t spend a dime. I spent something better. I spent a no.

My daughter learned to hear the sound it made and to make that sound herself. My grandchildren learned their grandma’s door doesn’t close for politics. My husband, who loved compounding more than any man ought to, compounded a trust into a life.

If you are standing in someone else’s lovely kitchen holding a casserole they didn’t ask for and they tell you they need space, give it to them. Then give yourself a room with a table where you decide who sits and what is served.

And if they show up later needing you to sign away your independence, remember: you are not a cosignature. You are the paragraph that changes how the story ends.

END!

News

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call. CH2

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call …

BREAKING: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in America had dared to ask to do before. CH2

LATEST NEWS: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in…

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour. CH2

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour Part One I…

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments. CH2

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments Part One It’s been said that family…

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About. CH2

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About Part One…

My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office. CH2

My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load