My daughter told me to run when my husband left for a business trip.

Part One

The Miller House in Portland, Maine, had a way of holding time like a photograph with depth—layers that revealed themselves to any resident who cared to look closely. Its tall windows reflected a bright, sometimes crooked light, and the brick façade held decades of winters and springs in its pores. The wooden staircase creaked in places that were familiar enough to be comforting and strange enough to remind Caroline that nothing remained static for long.

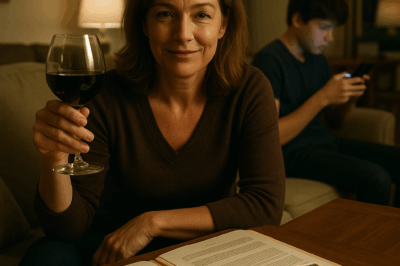

Caroline Miller paused at the kitchen counter, listening to the creek of the hallway floorboards above. Those sounds, to anyone else, might have been flaws. To her, they were the echo of a life made up of small, repeatable actions: coats hung on the same old peg, a chorus of shoes on the mat, plates stacked in the same cupboard. She had lived here with Daniel for fourteen years. They had raised Sophie together for six. The house was an archive of their days.

From the living room window a small voice called, “Mommy, look! The clouds are making animals.” Sophie’s tiny hand pressed against the glass as if she could touch the sky. Caroline smiled and poured orange juice into a glass, carrying it to the table. The domestic scene was ordinary, warm, and tender—an ordinary morning that hid the way the edges had been changing for months.

Daniel Miller came down the stairs immaculate and composed. At forty, he had the polished manner of a man who’d learned how to look as if everything were under control. He touched Sophie’s hair lightly, kissed her forehead, and told her about an important meeting that weekend. “Daddy will bring you a special gift,” he said. Sophie’s eyes widened with belief; the world was still generous enough to promise surprises. Caroline watched him and felt a tremor of unease she could not easily name.

The months since Caroline’s mother had passed away had been raw with grief. The will, the estate taxes, the careful sorting of old letters—those things were known and expected. What unsettled Caroline was the subtle shift in Daniel’s tone and in some of his habits. He was on his phone more often, answering calls with a discretion that made casual secrecy seem like performance. He was quieter at night, a shadow behind the habit of making coffee at dawn.

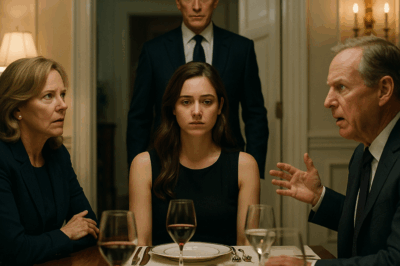

Then there was Daniel’s mother, Evelyn. Elegant, precise, and quick with the compliment that carried condescension like a scent. She visited unannounced, in a way that was never helpful and always exacting. With Sophie she was adoptive grandmother—close, involved, affectionate—but the affection came with conditions. Caroline noticed how Evelyn watched her with a faintly critical eye, as though she kept an account of every tilt of posture and wrinkle of a blouse, subtracting it from some imagined ledger of acceptable manners and achievements.

Caroline threw herself into her work at the Portland Art Museum; the exhibition she was planning—an homage to forgotten women artists of the twentieth century—was her anchor. She spent afternoons curating, fundraising, coaxing loans for fragile paintings from collectors who feared letting them see daylight. The work grounded her in a rhythm that felt honest, and yet, at home, something else moved like a low tide underfoot.

One afternoon Sophie came to her study with an old photograph—Caroline as a child, a sunburned hair, the kind of faux pride that belongs to people who believe in summer as ritual. The little girl held it like a relic. “Mommy, is this Grandma?” she asked.

“Yes,” Caroline said. There was a pause as Sophie studied the picture. “Grandma talks to me sometimes,” the child confided.

Caroline laughed on the outside because what do you do when a six-year-old claims to be visited by ghosts of kind grandmothers? On the inside she felt a little shiver. Children fold the world into myth in the most alarming ways. A week later Sophie added, almost conversationally, “I saw Daddy on the phone with Grandma Evelyn. They were whispering. Daddy said you would not notice.”

Caroline’s laugh did not come then. The thing you notice first about a whisper is its cruelty; the next thing you notice is how it marks you. “Sometimes adults keep secrets for work,” she said, more to soothe herself than Sophie. Yet the seed had been planted: hush, an instruction; watch, without telling.

Late at night she drifted past Daniel’s study, expecting the door to be closed. For the last few months it had sometimes been left unlocked, the stationary pile more slanted than before. That night, the drawer that had always been locked was open a fraction. Caroline’s curiosity—one of the qualities that had gotten her into trouble and out of it in the same measure—pulled her forward. There, among the files and the neatly alphabetized envelopes, was a life-insurance policy. The policy had been taken out just a week after her mother’s funeral. The figure was high—spare, in a way that made the chest tighten. The beneficiary: Daniel.

She replaced the documents with care, shrugged the thing away with rationalizations—a cautious man making arrangements for his family—and told herself not to spin from suspicion into accusation. Still, she could not stop the small fret at the base of her throat.

Friday brought business as usual: the school run, museum donors, a recipe to test for a winter fundraiser. Daniel kissed Sophie and left with his suitcase, promising the “big meeting.” That evening, Caroline noticed a man in a dark coat walking around the edge of the property. He paused by the garage; the movement made her stomach drop. She closed the curtains and tucked Sophie into bed earlier than usual.

Later that night Sophie crept into Caroline’s room, clinging to her stuffed rabbit. Her voice was tiny. “Mommy, I dreamed about the basement. The old servant’s basement. Grandma told me it was for hiding when bad people come.”

Caroline swallowed. The house had a sealed-off portion in the cellar, a legacy of the way people had lived a hundred years before. It had been mentioned in the property report when they bought the house, a historical curiosity. She made light of it in Sophie’s presence—imagination was a child’s special kingdom—but there was a part of her attentive to that tender, alarmed thing: the way a child speaks with clarity about what she has seen in the margins.

Hours later, sometime past midnight, Caroline woke to the faint smell of chemicals—gasoline. An odd, almost metallic tang in the air. She sat up and moved carefully to the bedroom door. A distant mechanical sound became clearer. Her hand flew to the knob of the back door. It would not open. She tried the side door. Locked from the outside. A soft but terrifying hum followed as shutters descended, sealing the house with a finality that made her lungs seize.

Smoke weaved under the kitchen door. The small noise that had sounded mechanical became an angry hiss. “Sophie!” Caroline called. The child ran, small slippered feet thumping. They met in the hallway where the air thickened with heat. Sophie’s face was pale but resolute. “Mommy, we have to get out,” she whispered. “Grandma told me.”

Caroline did not hesitate. They went to the pantry because children sometimes carry secrets that adults do not remember; because it was a small room and the memory Sophie claimed came from the grandmothers’ stories. Caroline pushed down the lowest shelf the way her mother used to reach for preserves in winter, and they found a panel—a narrow doorway into darkspace.

The house was no longer a refuge. Flames licked under the beams. They crawled through the passage in the dark, soot in Caroline’s hair, the panic a hot wire under her skin. The passage ended in an old shed with a rusted door that opened to cool night air. They tumbled into the yard, coughing, and the world tilted and then steadied.

The Miller home became a pyre as neighbors gathered in the street. Caroline stood on her neighbor Barbara’s porch, wrapped in a blanket, Sophie with the rabbit pressed to her chest. They watched flames swallow their life. The sirens came like an answer and the firefighters worked with the clinical rhythm that leaves only a charred silence when it is done.

Caroline’s voice shook as she told the officer—Lieutenant Harris—that she suspected arson. The life-insurance policy and the timing of Daniel’s sudden “business trip” had lodged like a pebble in the shoe of her reasoning. She showed photographs stored in her phone: images of the policy, a screenshot of Daniel’s hurried call schedule, the tiny piece of evidence that forms the beginning of a chain.

Sophie tugged on her sleeve. “Daddy said if Mommy was gone, everything would be his,” she said with the unflinching directness of a child. “He said it should look like an accident.” The investigators looked at each other, then at the child, then at Caroline. Children can be unreliable witnesses, the law says. Children can also be the clearest voices in a world gone murky.

The early forensics were grimly efficient. Traces of gasoline were found. The locks and shutters had been tampered with externally—remote triggers, cut wires. The security company’s logs showed a curious pattern of remote activations—doors and shutters controlled on someone’s account. Phone records revealed calls between Daniel and Evelyn in the days leading up to the fire.

Daniel, who had disappeared when the house burned, was found at a rest stop a state away with a trunk full of cash, false identification, and a burner phone. When the police arrested him, it felt like something else had been unmasked: not merely a man on the run, but a contraption of lies that had been built carefully to look like security.

Under questioning, Daniel lashed out and, in a moment that would become the legal pivot in the case, blamed his mother. His voice was bitter in the interrogation room. “It was her idea,” he said. “She’s always wanted me to be more. She wanted something else for our family.” Evelyn, when brought in, could not rein in her temper. In private, she clawed for control and told investigators with a scorn that disguised shame: “I did it for him.”

The motive that tied the fragments together was simple and ugly. Daniel was drowning in debt; he had been maintaining appearances with loans and a clandestine liaison across state lines. He needed money. Evelyn saw the life-insurance policy as a solution and, together, they had plotted to make a death—an “accidental” one—accrue to Daniel. Their cruelty was that of people who will rationalize anything to rewrite the story in which they belong.

Caroline and Sophie survived because of a girl’s dream and a mother’s swift, awful clarity—an act of small courage in a moment that made the world seem enormous. The community rallied. Barbara took them in first. People brought hot soup, blankets, toys, and in a week an online fund had been started by someone in the neighborhood to help the mother and daughter find a temporary apartment. Then the legal wheels turned.

The trial began in the bright room of the courthouse three months later. The prosecution set out a narrative anchored in evidence: the fuel found at the house, the tampered security system, the web of calls and money flows that led from Daniel’s accounts to Evelyn’s. Photographs of Daniel’s debts were displayed. The prosecution used forensic timelines to show that the “business trip” had been fabricated and the burner phone had been in use minutes after the remote shutter closing.

When the prosecution called Sophie to the stand, the courtroom inhaled and held its breath. A six-year-old in a poplin dress and with a stuffed rabbit at her side walked up with a quietness that made the whole room sit straighter. Her voice was clear. She told the story—not with rhetorical flourish but with the blunt, honest, and terrible precision of a child who had seen the worst and spoken of it without adornment. She described overhearing a conversation, the voice of the “Grandma” who had told her to be careful, the instruction that things should “look like an accident.” The judge paused, the jurors looked on, reporters scribbled and later called the child “the little hero.”

The defense tried to make much of Daniel’s mental state—pressure and desperation—but the paper trail and the corroborating evidence made the attempt thin. The jury returned guilty on charges of attempted murder and arson. Daniel would spend fifteen years in prison; Evelyn was found guilty of conspiracy and sentenced to eight years. The verdict was not a vindication that erased pain, but it was a legal account that recognized the scale of their wrongdoing and prevented them from hurting other families in the same way.

Part Two

When the fire was finally extinguished and the investigators had done what they needed to do to document and preserve the case, Caroline began to think about the long, quieter work of repair. Justice had been served in the form of sentences and verdicts, but recovery is not a courtroom exercise. It unfolds slowly, in the small minutes and hours when you realize you can stand without shameless shame, when you make a phone call not meant to manage other people.

They moved into a small cottage on the edge of Portland, a house with a blue porch that made Sophie exclaim and then run to explore. The house was modest compared to the Miller estate—no grand staircase, no formal mantle. But the rooms were honest and felt safe in a way the burned-out house would never be again. Caroline gave herself time and room to grieve; to be angry; to feel the precise oddness of losing a memory-laden house and a marriage at the same moment.

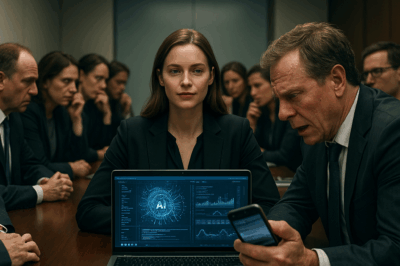

Work at the museum helped. Caroline poured herself into the exhibition and into a new idea that had been gestating for months: a foundation that would support young, underrecognized female artists—women who, like the artists she curated, had lived on the margins of recognition and had the vision without the infrastructure to realize it. She named it the Second Light Foundation because she believed in the capacity of life to offer a second, unexpected brightness after darkness.

Opening the foundation consumed her in a way that balanced grief with meaning. She used part of the inheritance to fund it. It was not a vanity project; it was a deliberate attempt to transform a source of strife into something generative. Artists who received grants traveled in from other places, bringing their messy practice and their hopeful stubbornness into a community that responded with the curious tenderness of seeing new work for the first time.

Sophie, for her part, began to heal in the way children do when they are allowed to be children again. Dr. Michael Hayes, a calm and patient child psychologist, offered sessions that were simple and steady. He taught Sophie to make safety plans and to draw her feelings in sketchbooks. Her art—bright and startling—featured boats, houses, and three figures in loving, warm colors. One piece, of her, her mother, and her grandmother walking along a shoreline, was chosen for a student exhibition at school. Caroline framed it and put it in their hallway where it glowed.

The community around them was complicated but mostly kind. Neighbors visited with cookies and wood for the fire. Barbara, the neighbor who had sheltered them during the night of the blaze, took on the role of an older, no-nonsense aunt. She brought over casseroles, sat with Caroline in the small living-room and listened to her process the surreal facts of betrayal by a spouse and a mother-in-law. Barbara’s friendship had the directness of someone who’d seen hardship and refused to sugarcoat it.

Caroline’s daily life reassembled itself into new patterns. She taught, curated, and led the foundation with a quiet authority that started to feel like a natural state again. The small things mattered: a walk to the bakery where the owner learned Sophie’s favorite treat, the way a certain bench in the park caught the late sun. She learned again how to go to sleep alone without the weight of fear.

As the legal dust settled, Daniel and Evelyn’s presence retreated into a scarred corner. The press ran human-interest pieces—profiles of Caroline and Sophie, the “little girl who saved her mother.” Those stories were uncomfortable in their attention, but Caroline reframed the narrative by speaking about the necessary vigilance of listening to instincts and the way a community could protect one another.

There were complications and awkward apologies. Brian and Danielle, their pride badly bruised, had to reckon with the fact that their attempt to “help” had been born of assumptions about Caroline’s fragility rather than conversations with her. Dialogue returned slowly. They visited on terms Caroline set: short lunches, rides to appointments when she needed them; no surprise plans. Caroline accepted apologies that were honest rather than grand pronouncements. Time is a teacher of small decency.

Caroline found companionship in a manner that surprised her. Dr. Michael Hayes, initially a neutral therapist helping Sophie work through her nightmares, became a friend. His presence was not dramatic—no swooping love story—only an example of two adults who enjoyed shared dinners and conversations about ordinary things. He listened, which is a rare kindness. He went to exhibitions with her, and they spent quiet afternoons discussing artists and memory. He never erased the past and never rushed her healing. When he became a person she liked, she allowed herself to notice it without shame.

There was also a fracturing in the Miller circle that could not be easily given a neat narrative. Some of Daniel’s old colleagues distanced themselves; a few defended him desperately in op-eds filled with speculation; some of Evelyn’s friends were appalled and shamed into silence. The family that had been a fortress of social ties loosened in the absence of the central figure who had wielded charm like a weapon.

In time the museum exhibition opened to a modest crowd and then to serious attention. Caroline’s curation of the forgotten women artists captured an undercurrent in the city’s cultural center: an appetite to reassess the canon and to shine light on work that had been overlooked. The Second Light Foundation had events that worked in the edges of the museum’s offerings—small residencies, an open house for women pursuing art after midlife. Caroline became a speaker at panels and a mentor to younger curators. Her life reconstituted around a mission that took the sting out of loss: turning private sorrow into public generosity.

Sophie, who had once been called to the stand in court, grew into a child who understood that courage came in many shapes. She learned to trust that adults could be both fallible and good. She had sleepovers with friends whose parents ran to the park with them. She started piano lessons in spring and drew for hours in a corner of the foundation’s community room that the local kids used for painting. The rabbit that had been with her on the night of the fire became a sort of talisman, a soft thing that marked survival.

One winter evening, as snow began to fall and the cottage lights blinked warm, Caroline received a letter from the parole board’s administration—an odd bureaucratic envelope that meant little to her day-to-day life. Daniel’s sentence had a scheduled review in a few years; there would be no early release yet. The idea of him existing behind bars was not something she celebrated; it felt like a legal safeguard that allowed her to keep living rather than breaking.

On Christmas Eve that year, Caroline and Sophie sat by a fire that did more than warm bodies; it warmed the smallness of living that had been reclaimed. They had stockings, a modest tree, and a kettle of cider. Sophie brought out a drawing for Caroline—three figures on a shoreline, again. “Grandma helped us,” she said, as softly as one might read a prayer.

Caroline kissed her forehead and laughed, the sound bright and raw. “We saved each other,” she said. The words were a tidy truth she cherished. The “we” included Sophie’s bravery, Barbara’s neighborliness, the detective who had believed in small facts, and a judge who read a pile of evidence and recognized the pattern of planned violence. It included community and slow apologies, and it included the work Caroline had found meaning in.

Years later, Caroline would visit the site of the old Miller house. The lot had been cleared after the insurers completed their assessments and the legal claims resolved. A small plaque at the frontage acknowledged that a home had once stood there, and the new saplings suggested a future that would not reclaim what had been lost but might grow something different from the ground. Standing there, she felt something close to completion: no triumph, only a roundness of knowing that a life had been remade.

The foundation thrived. Caroline visited artists in residencies and tutored interns in the curatorial arts. Sophie studied in school and grew into a girl with a fistful of artistic determination. She wrote letters to other children at the pediatric wards and drew pictures that were later sold for small sums to raise funds. She grew into a kindness that had been tested and hardened into compassion.

Caroline sometimes thought of Evelyn and Daniel not with the heat of hatred but with a kind of authorial pity—their story had become a tragic study in how ambition, when untethered to empathy, can infect those nearest it. Their sentences and the public shame that followed did not erase Caroline’s memory of better moments; they complicated it. She learned to live with complexity rather than the vengeful satisfaction that novels sometimes promise.

One distinct afternoon, years after the fire, a ceremony was held for the dedication of a small bench in a playground near the cottage—a modest piece of wood engraved: In memory of what we loved and in witness of what we saved. Brian and Danielle attended, with their children, faces a little older and shaped by time. They had made choices differently since the trial. They had learned that protecting someone meant asking them what they wanted, not deciding for them.

Caroline ran the foundation now with a team who revered her tempered steadiness. The Second Light grant applications arrived in stacks and were read in long, focused sessions over tea and bread. Artists came, created work, left, and brought others back in a slow cycle of generosity. The building was a modest house turned gallery, where community members could meet. It was a place of clean light and careful listening.

In the quiet moments, Caroline would sit by Sophie’s desk and look at the small drawing of three figures on a shore. It hung in a spot where sunlight found it every afternoon. She thought of the way that little girl had pushed aside a pantry shelf and led them through a secret path under a house that would have been their tomb. She thought of how easy it would have been to ignore that kind of small courage, and how many lives might have been different if more people had trusted what a child said.

When I tell you this story, I do not do it in triumph; I do it because the quiet logic of survival matters. Listen to your instincts. Value the small guardianship of neighbors and friends. And above all, know that rebuilding takes a particular kind of stubborn kindness.

On a clear morning with the lemon wind of a distant life only memory can recall, Caroline watches Sophie paint at a little table by the window. Sophie, now older and steadier, hums as she mixes colors. There is no sensational ending—the world rarely hands those out. There is instead a tidy and luminous truth: they are safe, they create things they love, and they teach others to do the same. That, to Caroline, is an ending that belongs to reality: not dramatic, but whole.

The last lines of the courthouse transcripts remain a cold record. The softer lines—Sophie’s hand on Caroline’s—remain the warm record. Their life, like the Miller House and its quiet disasters, is a story of mistakes, of dark turning points, and of the ways that courage and community can become the scaffolding for a new life. If anything remains clear after all these years, it is this: the little voice inside us that says “run” sometimes saves more than bodies—it saves the possibility of a future.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

After I became a widow, I never told my son about the second house in spain. glad i kept quiet… CH2

After I became a widow, I never told my son about the second house in Spain. glad i kept quiet……

My Fiancé’s Rich Parents Rejected Me At Dinner — Until My Father Arrived… CH2

My Fiancé’s Rich Parents Rejected Me At Dinner — Until My Father Arrived… Part One The grandfather clock in…

My Backstabbing CEO Stole My $4 Billion AI — Until It Mysteriously Started Exposing His Secret Plan. CH2

My Backstabbing CEO Stole My $4 Billion AI — Until It Mysteriously Started Exposing His Secret Plan Part One…

My Stepfather Called Me a Maid in My Own Home — So I Made Him Greet Me Every Morning at the Office. CH2

My Stepfather Called Me a Maid in My Own Home — So I Made Him Greet Me Every Morning at…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Slapped Me In The Face Just Because The Soup Had No Salt. CH2

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Slapped Me In The Face Just Because The Soup Had No Salt Part…

At Christmas Dinner, My SIL Laughed “Your Gifts Are Always Cheap And Useless” – Until He Opened the present I gave him. CH2

During Christmas dinner, my ungrateful son-in-law mocked me, saying, “Your gifts are always cheap and useless.” The whole room went…

End of content

No more pages to load