My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office

Part One

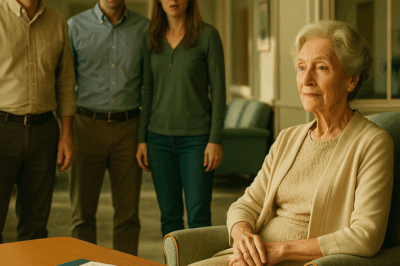

There is a second in a life that snaps you awake. For me, it was not dramatic in the ways movies like—no car crash, no thunderclap—just the soft whirr of a boarding pass printer at Gate 42 and my daughter’s voice, professional and brisk, saying, “Mom, hi. We need to talk.”

I had raised Rebecca to be strong, to be independent, to arrive polished and prepared. She arrived that way. Cream sweater, flat gold hoops, hair that looked breezeless in an airport. She had her husband with her—the phone-checking, eye-avoiding kind of sorry—and two grandchildren who hugged me distractedly as if they had boarded in their heads already. She did not say I looked nice. She did not ask if I’d had breakfast. She said, “There’s been a change of plans. We can’t take you with us.”

Words have weight. Those sank through me with the steady gravity of a stone thrown in a lake. We had planned this for months. I had packed carefully, in the slow, loving way women pack when the trip is as much dream as destination: navy pants suit my daughter had once complimented, passport tucked into the leather folio she’d given me for Christmas, blister-plaster bandaids (motherhood is a muscle memory), Spanish phrases I’d tried in the bathroom mirror: Buenos días, buenos tardes. It would have been my first time watching monkeys with my grandchildren.

“You know how it is,” her husband Dave said to a spot over my shoulder. “Company policy. My boss is joining. It’s more of a business trip now.”

I knew how lies look on people who want them to be true. Rebecca touched her earring. She could not hold my eyes for two full seconds. She used the voice she used with cranky clients. “I’m really sorry, Mom. We’ll call you when we get back.”

The speaker announced pre-boarding. My granddaughter Emma, twelve and soft-hearted, tugged on her sleeve. “But Grandma was going to see the monkeys,” she said, and Rebecca said, “Emma,” and gave her the smile women give their daughters when they’re practicing a tone they don’t like on them yet.

“What is it you want them to remember about this moment?” I asked, and I wasn’t sure which of us I meant. Guilt flickered and died in her face like a television losing signal. Then they walked. I watched my only child hand her family’s passes to the agent, watched that agent smile at them the way people smile at families on trips, watched them disappear into the intestine-bright tube like the inside of a whale in an illustration.

I stood until their plane pushed back and I could not see the nose through the glass anymore. Then I picked up the small rollaboard whose weight I had chosen and whose weight I would keep and walked back through the airport. At baggage claim I sat in one of those chairs built to remind you this is not your living room and took out my phone to call a taxi.

Instead, my finger scrolled past the taxi and pressed a number I know as surely as my own. “Peterson Aviation,” a voice said. “This is Anna Washington. I need a Chicago flight wheels-up within the hour.”

“Same aircraft, Mrs. Washington?” the voice asked, in the tone of someone who has seen a woman more than once in her full form.

“Yes. And please set the cabin for a working flight.”

When a person leaves you at a gate, they think you will go home to hurt and pajamas. It is a gift to yourself to go to a runway instead.

The leather seat has a way of making you sit straighter, not because of leather but because of what you remembered you were capable of when you arranged to sit there. As we lifted, the city fell away in grids and silver seams of highway, and I remembered the times the woman named Anna had made choices that were not about being liked.

I had been a good wife, but before that I had been a good businesswoman; and after Walter died, I had pretended those facts were mutually exclusive. I had stepped out of my company’s daily life with what I told myself was grace and what turned out to be camouflage. I had remained a partner and a shareholder and a board member in rooms where leverage is not a metaphor. I had not told my daughter because I had wanted her to feel successful, to build her own mountain in the air and then bring it down. I believed I was giving her space. In practice, I built a stage where she could forget I was a person.

The jet’s interior is designed for decisions: a table that unfolds like a chessboard, a line of quiet lamps, Wi-Fi that doesn’t ask if you’re sure. I made three lists between Denver and Chicago. One was money, the grammar of consequences. One was memory, the timeline of grace and its absence. One was what I wanted from the next fifteen years of my life: a vocabulary of self that did not start with mother and end with silence.

At Jonathan Patterson’s firm—the kind of glass-and-mahogany place that tells a story about who you are before you open your mouth—the receptionist doesn’t blink when you ask for the senior partner because he has already called her to say whatever she needs. Jonathan’s hair is white in the way that tells you a person has earned it, not found it.

“Anna,” he said, with a lawyer’s handshake that says we will be plain with each other. “Your call intrigued me.”

“I need three things,” I said, setting my leather folio on the table that could host a last supper. “I need to revoke every ongoing financial arrangement I have with my daughter. I need to explain it in a letter that will be Exhibit A when she calls me cruel. And I need to do it in a way that would make your former professors proud.”

He listened the way good men do: with his mouth closed and his pen moving. When a woman tells a man that her daughter left her standing at a gate, a decent man looks like he is ashamed of his sex. He did. Then he began to draft. As he wrote, I called banks I have never visited in person, because wealth done correctly is gerunds and routing numbers. I canceled the autopay on a mortgage that had lived under my kindness for a decade. I called the private school and told them my semester would conclude and their relationship with me would not. I halted the subconscious river of money that had been flowing long enough to erode bedrock. I did not falter. I was startled, though, at how many numbers were there when you added them to themselves: down payment, monthly supplements, tuition, vacation contributions, the cars that start but do not purr.

“Do you understand,” Jonathan asked, “that this will create an upheaval in her life? She may not forgive you.”

“People who love only the part of you that hands them a check have nothing I need forgiveness from,” I said. “Send the courier.”

In the sedan back to the private terminal, my driver Thomas asked, with good manners and too much heart, “Everything all right, ma’am?” and I said, truthfully for perhaps the first time in a year, “It is going to be.”

Saturday morning she called. She used hell in the way adult daughters use when they want to sound like they are eighth graders testing a word. She said, “What is this?” and “You can’t,” and “We depend on that money,” and I said, “Which part? The part where you assumed my generosity is a utility? Or the part where you think dependence is something you’re owed?”

I did not raise my voice. I did not apologize. I said, “You are forty-three years old. You and your husband have degrees and salaries. You will sell the house you cannot afford. You will move to a school district where the school is the one you can afford. You will cook more dinners than you order. You will find that public schools build fine children. You will go to used car lots and discover that humility is good for engines. And you will stop calling your mother only when you need her wallet.”

She tried the tactic of restaurant peace: “Let’s meet somewhere nice and talk this out.”

“At your house,” I said. “I’d like to see what my monthly checks have been maintaining.”

That afternoon in my living room, high above a city that knows what it is to make itself, I watched my daughter look around at a life she didn’t know I lived. She asked the sensible questions. “How?” “Since when?” I answered not with a list of numbers (though I had those) but with a list of choices. I stayed small to make you comfortable. I am done with that now. I am a person. You will see me as one or you will not see me at all.

Dave, who is an engineer and thus likes variables and outputs, asked, “What do we do?”

“Work. Decide. Fail and re-decide. Sell the house. Enroll your children in a school where the cafeteria smells like the same food everyone else is eating. Tell Emma that no one’s worth is their zip code. Tell Michael he can try baseball because equipment on eBay is cheaper than lacrosse sticks. Tell yourselves the truth in rooms where no one else can hear you. And call me on Tuesdays without an agenda.”

Before they left, Rebecca looked out at the lake and said the first true thing I’d heard from her in months: “I don’t know how to be your daughter if I can’t count on you to help us when we need it.”

“You will learn,” I said, and it sounded less like a threat than a blessing.

She did not call for three weeks. In that interval, I bought a penthouse. I called my stylist and remembered that a woman who ran a company does not have to apologize for a navy dress that fits like it was sewn by someone who knows what architecture is. I moved breakables onto shelves at a height that told me I was the one who decided where things go. I returned full time to the business Walter and I had built from late-night grit and coffee Mr. Coffee wouldn’t have recognized. At the Morrison table, men who had not seen me in a decade nodded like someone had opened a window. Welcome back was on their faces in two languages: relief and respect.

And she did call. And she did come. And she did sit on my cream sofa and turn pale at the marble and then try the tactic she had learned at work when her boss asked why a campaign hadn’t landed: Let’s fix this. And I told her: there is nothing to fix that a house sale and a recalibrated life won’t.

“I am happier,” she said to me six months later, with eyes that meant it. “That sounds wrong, but it’s true.”

It did not sound wrong to a woman who had watched her daughter’s spine lengthen under unassisted weight. Rebecca started a consultancy. She delighted called me to say I signed a client the way people call to say the baby rolled over. Dave came home earlier because overtime is less necessary when you sell the house that eats overtime whole for sport. Emma got a science teacher and started talking to me about genetics at the same time she discovered her grandmother’s mathematical brain. Michael learned that the kid with the best sneaker brand is not the kid you always want to sit next to on the bus.

We had lunch every other Tuesday. She brought me a vase she had thrown in a pottery class. I put it where the sun hit it in the afternoon. We talked like two grown women who liked each other, about work, about books, about a TV show with writing sharper than a box cutter. When she asked, “Are you lonely?” I said, for the first time in a long life, “Not anymore.”

When I told her I would leave most of my money to strangers—women who needed loans more than my family needed a second home—she did not flinch. She said, “Thank you.” Then she offered to help me build the foundation that would do it right, without the whiff of noblesse oblige. We designed programs that require sweat equity and weekly check-ins and the kind of mentorship that is not a holiday card but a calendar item.

By summer, we planned a vacation—not Costa Rica, not because of sting but because of truth. We rented a lake house in Wisconsin with mismatched plates and a living room rug that probably has hosted someone else’s family argument. We made pancakes. We bought corn on the side of the road and Emma taught me to shuck it “the efficient way” TikTok taught her and I taught her the joy of doing it slowly over a trash bag while you talk. We drove to a county fair and spent twenty dollars to win a stuffed dolphin smaller than the gas money to get there. It was perfect because no one’s dignity was a line item.

On a Tuesday afternoon in late autumn, as sun melted into a skyline that knows nostalgia intimately, my phone lit with a name that has become a bell. Emma. “Grandma,” she said, breathless with the pride of a child understanding something adults were slow to, “I wrote my science project on inherited traits. I put math from you and pottery from Mom and Dad’s stubbornness. Is that okay?” I told her it was a perfect genotype. She told me I looked pretty in the photo her mom had put on the first page. I looked at the picture and saw a woman who had been left at a gate and did not sit down.

Part Two

Six months after the gate, the foundation papers were signed in a room that smells like leather and lawyers and fresh starts. The Anna Washington Foundation for Women’s Business Development is a name that would embarrass an earlier version of me; it thrills this one. Ten million dollars seeded into a plan that is not just grants but frameworks: microloans paired with mandatory financial literacy classes, mentoring circles led by women who have run payroll and know what it means to not take home a salary so their employees can. Rebecca sat opposite me with a notebook full of arrows and words like funnel and outreach and comms plan, and I thought: this is what inheritance actually looks like—skills, not checks; courage, not cheques.

I wish I could tell you this is where every bow tied itself. That Martha sent a card with I was wrong and a casserole with butter in it. That Richard shook my hand again without pining for equity. That Dave stopped trying to quantify everything and learned to sit in emotions with the same patience he gives a stubborn prototype. In truth: people change at the velocity they can bear, and yours is not the accelerator. Martha called a few times to see if I would reconsider my estate plans; when I told her no, she told me about a woman she knew who “lost everything to charity,” and I said, “She found it.” Richard invited me to his club for lunch; I said I had plans and did not lie to make him feel better about my no. Dave said, after a beer too many, “I had no idea money was power for women the way it is for men,” and I said, “Now that you do, never forget.”

Rebecca relapsed twice. Not into money—she didn’t ask for that again—but into repertoire. Once, she called on a Sunday and said, out of old habit, “Can you watch the kids? We have a spa day,” without please and with the tone of a calendar entry. I said, “No, but I would love to take them Thursday to the museum if that works.” It hurt us both for thirty seconds and then it didn’t. Another time she met Martha for lunch and came back with an edge, the kind children get when they return from camp where counselors say quests in place of choices. She said, “Mom, does everything have to be a lesson?” and I said, “No. Sometimes it’s a cake.” We baked one together that afternoon in my kitchen, the expensive one. It sank in the middle and we ate it anyway.

The hardest piece was an inheritance conversation. We had it on a morning that was clearer than the view. It felt like writing a will with someone alive enough to argue with you. I told her I would leave her security, not latitude; education funds for Emma and Michael that could be used at any school that took both their brains and their hearts seriously; a trust to buy a house if she wanted without granite countertops dictating the zip code. I told her everything else would go to women who were me in the seventies and her in the twenty-twenties and don’t illustrate themselves on glossy brochures. She did not flinch. She said, “It will do more good out there than in my pantry.”

The day of Emma’s science fair, I wore flats because school gym floors are treacherous. Her poster was better than the others not because I am biased (I am) but because it told a story: grandparents with photos printed from a cloud (her other grandmother in pearls, me in a blazer), arrows that said math sense and stubborn joy and always show up. Under Always show up she had drawn a tiny airplane and written When Grandma boarded a different flight. It made me laugh and then it made me cry in that order. The judge, a man with kind eyes and a tie that said he probably grades papers at the kitchen table, asked Emma what trait she hoped her own children would inherit someday. She said, without drama, “Courage to stop pretending.”

The only person who hadn’t changed enough by then was me at twenty-five, the ghost of her. She walks my halls sometimes, holding a towel and a ledger, and asks, “Was it necessary to hide?” The woman I am now tells her: I forgive us. We did what we could with the information we had and the stories people told us about what good mothers look like. Then she pours her a glass of something and opens the doors to the terrace, and together we stand and feel air on a face that has earned it.

You might ask what happened with Gate 42. Memory does this thing where it tucks humiliation away because it is too hot to hold. Mine holds it in two ways: as a cautionary tale and as a pin on a map that says start here. Once, months after everything, I found myself at that gate again on my way to meet with a foundation in another city that wanted to partner. I sat in a chair that was designed to tell me I was not home and pulled out a book. A woman sat beside me with hair that said appointment and a face that said two jobs. She was on the phone with her daughter. Her daughter sounded tired with love and asked if she could help with the baby next week because daycare was closed. The woman said yes and I watched relief flood the space between them. After she hung up, she looked at me with tears that just touched her lashes and said, “They don’t think about us as people sometimes.” I said, “It is our fault when we teach them we aren’t,” and then I bought her a coffee and two muffins because lesson and cake, always both.

On a winter evening that dressed itself like spring, my foundation held its first pitch night. We did not call it that. We called it Tuesday. Thirty women crossed a room full of tables and fear and told someone with a checkbook and a past like theirs what they wanted to build. We funded nine, fully, and paired each one with a mentor who knew how to navigate a loan officer and a sick kid and an invoice that is ninety days past due. Rebecca stood at the podium and introduced our keynote—me—and I told a room full of women, “You are not charities. You are investments. And you will return tenfold.”

Somewhere between applause and the excellent cheese board, my phone buzzed with a text from my daughter. We booked the cabin. The one in Wisconsin with the canoe docks and the noisy frogs. You’re in the bunk room with Emma because she says you’re the only one who tells stories worth staying up for. I typed back a single word I have earned: Yes.

This is the part where I am supposed to say something wise, so I will not disappoint. Here is what I know now, cash and heart together: Money is a lever. Dignity is a foundation. Love without respect is a siphon. Enabling is theft of a future you are pretending to protect. Motherhood is not martyrdom; it is leadership. If you have spent years making yourself small to cushion other people’s leaps, you will not see their faces when they land. Stand up. They will learn to aim. They will also miss sometimes. That is what towels are for.

The final scene of this story is not a gate or a signature under a lion’s-head letterhead. It is a table in a small kitchen that cost less than my office chair where a twelve-year-old is teaching a seventy-four-year-old to center clay. The woman’s hands are steady because she has practiced steadiness for decades. The girl’s hands are messy because she is learning, and nobody has told her mess is shame. The daughter is at the sink, humming because she is happy and she does not know she is humming because that is how happiness always sneaks out. We make a vase that is not perfect and we put daisies in it anyway and we put it where the light hits in the afternoon.

My phone pings. It is Emma again: a blurry photo of a frog at dusk and the words, He is so loud. The doorbell rings. It is Rebecca and her arms are full of groceries. The evening unfurls.

Gate 42 sits where it sits. The private jet sits in its hangar, fueled and flight-ready because sometimes you still need to go to Chicago. The law firm’s conference room is still overly cold because men who run buildings think competence requires gooseflesh. Morrison’s boardroom still hums with the satisfying grind of a good deal done well. The foundation’s ledger now has a line item called tea and muffins for people while they wait to pitch, and I will not pretend it does not do as much good as the microloans. Martha still owns her opinion. Richard still wears his khakis. Dave still forgets not everything must be quantified. All of that is true.

But here is the truest thing: the woman they left at the gate has written herself a better story and invited them into it with terms. They said yes.

If you are standing alone under the hum of an airport vent with a boarding pass you will not use, please hear me: call the number that remembers who you are. Board the thing that takes you to the life you stopped letting yourself imagine. Teach the people you love that respect is part of love and that money is never a synonym for apology. Bake the cake, and make the list, and buy the dress that fits the person inside your bones. And when your granddaughter calls to ask which traits you hope she inherits, tell her the truth: Courage to stop pretending. Willingness to start anyway.

END!

News

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call. CH2

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call …

BREAKING: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in America had dared to ask to do before. CH2

LATEST NEWS: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in…

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour. CH2

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour Part One I…

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments. CH2

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments Part One It’s been said that family…

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About. CH2

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About Part One…

My Daughter Excluded Me From Her Vacation—She Had No Idea I Own The Resort She Was Visiting. CH2

My Daughter Excluded Me From Her Vacation—She Had No Idea I Own The Resort She Was Visiting Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load