My Daughter-In-Law And Her 25 Relatives Are Coming For Christmas? Perfect — I’m Traveling. They Can…

Part One

The first thing I learned about being a mother-in-law is that the job title will try to sneak center stage in your life if you let it. The second thing I learned is that people will confuse availability with obligation until you correct them. I am 66, my name is Margaret, and five years into playing unpaid live-in housekeeper under my own roof, I decided Christmas would be the night I corrected everyone.

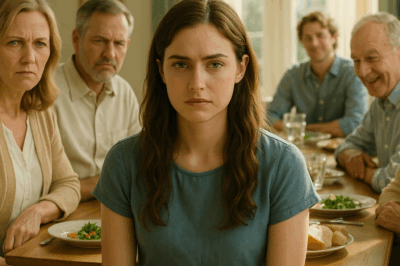

Tiffany didn’t knock. She never knocked. She flowed in wearing a red dress that matched her nails and her ambition, heels tapping an impatient metronome across my kitchen tile.

“Margaret,” she sang, like she was placing an order. “Marvelous news. My entire family is coming here for Christmas. It’s only twenty-five people.”

Only. She poured herself coffee with my mug and my cream and my quiet and settled into my chair as though gravity had always intended it for her. “I’ve already spoken with my sister Valyria, my cousin Evelyn, my brother-in-law Marco, my uncle Alejandro. Everyone is coming. We’ll need three turkeys at least, the chocolate silk pie you make, and all your decorations. The house must look perfect for Instagram.”

There was a time I would have nodded and reached for a notepad—a time when I believed keeping my son’s wife comfortable was the same as keeping my family intact. But grief makes you crystalline. With the clutter scraped away, you see where the light should go.

“Perfect,” I said, matching her smile. “It will be a perfect Christmas for you all, because I won’t be here.”

The word hung in the kitchen like a chandelier whose chain had just let go. For a heartbeat, Tiffany’s face lost its architecture. Then the scaffolding snapped back up.

“What do you mean—won’t be here?” Her voice cracked on the last word, as if it had never been allowed to bend before.

“I’m going on vacation. You all can do the cooking and cleaning. I am not the maid.”

Four words landed like stones: It’s my house. I let them sit between us. If we were going to say honest things, we might as well start with the foundation.

“You can’t do this,” she sputtered. “Kevin won’t allow—”

“Your husband can have whatever opinion he likes. My decision is made.”

Keys in the front door. The metronome of heels down the hall. Kevin’s tie loosened, not from long hours but from the habit of looking exhausted when you’re asked to do anything emotional. Tiffany ran to him as if she were leading a witness.

“Kevin, your mother has gone insane. She says she’s leaving us alone with my entire family.”

My son’s voice had taken on a patronizing tone since his wedding—an imitation of adulthood he thought sounded like authority. “Mom, don’t you think you’re being a little dramatic? It’s Christmas. A time for family.”

“Family consults the person who will be roasting three turkeys before inviting an army into her kitchen,” I said, rinsing my cup at a pace that made my calm feel heavy. “Family also does not leave muddy footprints on my clean floor, Kevin; take off your shoes.”

“All right,” he sighed, getting it and not. “But think about it. It’s one week. Then everything goes back to normal.”

“No, sweetheart. Things will not be going back to normal, because I’m leaving tomorrow.”

For years, I’d watched Tiffany assume future inheritance counted as current authority. “Our house,” she’d fretted when the plumber tracked dirt, as if legal documents were already written in the tense she preferred. That morning, she finally said it aloud—that one day this home would be hers. “Interesting perspective,” I murmured, tucking the confession away like a coupon I fully intended to redeem.

The truth: I hadn’t made a spontaneous decision. Three months earlier, while foolishly folding laundry in Kevin’s office, I found a stray folder with Tiffany’s name on papers that didn’t make sense. That night, after they went upstairs, I came back with a flashlight. Bank statements: secret cards in Kevin’s name he didn’t know about. Loans tied to my deed for “bridge cash.” Emails where Tiffany detailed how to “manage” Kevin—how to keep him distracted while she kept spending. Threads in which she instructed a cousin to “talk up Kevin to Uncle Alejandro” and promised a return “once we flip Margaret’s house for the new condo.”

My house had been slotted into their plans like a line item.

I hired a private investigator my lawyer had once trusted to check a closing price. A discreet man with comfortable shoes, he traced Tiffany’s narrative the way a tailor traces chalk: measurable excess in designer boutiques, loss-leader lies about income, a parade of small deceptions leading to three large ones. The picture sharpened: her part-time boutique job inflated for prestige; our family gatherings sold to her Miami relatives as proof of her prowess. She hadn’t just invited twenty-five people for Christmas—she had invited twenty-five witnesses to a lie.

So I made phone calls of my own.

I wrote to the handful of relatives whose opinions Tiffany seemed to breathe like oxygen: Uncle Alejandro (wealth), brother-in-law Marco (real estate), sister Valyria (finance). I introduced myself as a concerned mother-in-law. I attached photocopies “by mistake.” I asked for advice the way older women ask on purpose.

Alejandro wrote back within hours, all polite Spanish outrage and honor: We arrive early. We will speak with her privately. Thank you for telling us the truth. Marco cancelled any talk of condos. Valyria asked for the rest of the statements.

And I made a few household decisions.

I moved my savings to a bank Kevin didn’t have memorized. I deposited the deed into a protective trust with a clause that meant no one could use it to borrow without my signature, not now, not when I was gone. I placed my good china, Christmas linens, and heirloom ornaments into my bedroom and had the lock changed. I cancelled the cleaning service—one of Tiffany’s favorite ways to claim credit for invisible work I paid for. I wiped the pantry and refrigerator clean. If she wanted a perfect spread, she could discover that food does not appear in a dish just because you photograph it.

“Mom,” Kevin said now, swallowing, “at least tell us where you’re going.”

“To visit my sister in Miami,” I lied cheerfully; my sister died in 1998. In truth, I had paid for a fortnight in an oceanfront suite an hour away. I wanted a front-row seat, but I wanted room service more.

“You’re using our situation to manipulate us,” Tiffany snapped, exposing a vocabulary I recognized too well. “That’s emotional blackmail.”

“Emotional blackmail,” I repeated. “Like the years you lectured me about family when I refused to cater your friends’ brunches? Like the time you told me a good mother-in-law didn’t mind being invisible?” I smiled the way women smile when they are done being polite: all teeth.

At seven sharp the next morning, a cab idled in front of my house. I left a note on the kitchen table: Have decided to leave early for my trip. The house is in your hands. Enjoy your perfect Christmas. —Margaret. The spare keys sat beside it with a ribbon tied like a bow on consequences.

By ten, my phone shook itself silly with calls. I ate lobster thermidor on a balcony and let the vibration serve as background percussion. When I finally scanned my voicemail, I found panic creeping toward remorse.

“Mom,” Kevin pleaded. “The store doesn’t open until eight. Tiffany’s family hits the door at eight. What do we make for breakfast for twenty-five?”

Another message, Tiffany’s voice ragged: “Margaret, I know you’re mad, but please don’t humiliate me. My uncle came from Miami. There’s nothing in the pantry. Where are the plates? Where are the decorations? Just—tell me where you put everything. Please.”

I put the phone face down and listened to surf.

At seven-fifteen, the front desk rang my room with a long-distance call patched through. Alejandro. “Mrs. Margaret,” he said, his English careful and his patience shorter. “We arrive early. We wish to speak with Tiffany. May we see you?”

“You may see her,” I said. “I am traveling.”

He understood. “Then we will discuss this where the lies were told.”

From my hotel lobby that night, I hired a car to loop past my cul-de-sac. The house—and I say my with a pleasure I recommend for anyone who has felt their life shrink to the size of someone else’s expectations—looked like a set between takes. Rental cars, half-unloaded grocery bags slumped on the porch, a cardboard pizza box balanced on the mailbox like a punchline. Through the window, I saw Tiffany gesturing with an empty platter while Alejandro stood with his hands in his pockets, disappointment settling around him like a coat he hadn’t planned to wear.

The next morning was Christmas Eve. I packed my suitcase and called my attorney. He met me at ten with a folder full of paper that made Tiffany’s “our house” sound as silly as it had always been. When I opened the door, I found three versions of Tiffany: furious, fragile, and finally, frightened.

Alejandro stepped forward, extending a hand as if we’d met under a sky that wasn’t currently caving in. “Mrs. Margaret, at last.”

“Please, come in.” I led them not to the formal dining room where I had plated dinners while Tiffany posted, but to the kitchen table where real food and real words have a better chance.

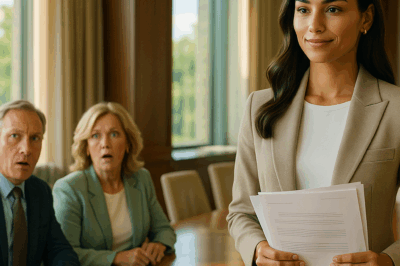

“I am Robert Miller,” my attorney said, setting his briefcase on the counter I’d scrubbed a thousand times. “Mrs. Sullivan has asked me to clarify a few matters.”

Tiffany’s eyes darted to the pantry, as if provisions might materialize to save her dignity. Kevin looked at the floor, as if answers lived in grout.

“First,” Robert said, “Mrs. Sullivan has moved the home into a trust. No one may sell, mortgage, or pledge this property without the trustee’s consent. That trustee is—”

“Me,” I said, because I liked the way it sounded, and because words you speak yourself sit better in your bones.

“Second,” Robert continued, “we’ve formalized terms of residency. Visiting hours, advance notice, chore contributions, expected conduct. Mrs. Tiffany will no longer be present in this home without invitation.”

I slid printed copies across the table. Tiffany stared at the bullet points as if punctuation could be cruel. “You’re banning me from my husband’s family,” she whispered.

“I’m inviting you back when you learn how to behave in mine,” I corrected.

Alejandro cleared his throat. “Before you worry about invitations, Tiffany,” he said gently and not, “you should worry about debts.”

Valyria spread her folder like a deck of stacked cards. Prints of statements with Tiffany’s signatures, Tiffany’s lies, Tiffany’s promises she used as collateral because she assumed I would die on schedule and generously. “Twenty thousand to cousins in Hialeah,” she said, tapping with a pen. “Seven here, four there. All with the story that Margaret is leaving the house, the savings—things she had no right to promise.”

Tiffany made a sound I hadn’t heard her make in five years: a small, unadorned oh. Naked truth dismantles women who have traded in pretty fiction; it’s a currency they haven’t handled and the metal leaves marks.

“And then,” I said, because we weren’t done, “there is the matter of identity fraud.” I slid a second folder—my investigator’s—across the table: credit accounts opened with Kevin’s information; inquiries that would be chasing my son’s credit score for years. Kevin flinched like a man dodging a thrown plate that never came.

“I didn’t know,” he said, and this time I believed him.

“That,” I replied, “is precisely why you need to learn. I cooked your dinners. I changed your diapers. I cannot clean up this mess.”

The doorbell rang again. My lawyer opened it to two officers and the building inspector. The inspector was there because neighbor complaints about cars and noise required someone to be official when talking about occupancy limits. The officers were there because my attorney had filed for an order of protection that morning. Timing is a kind of ingredient—you add it at the right moment or your dish refuses to set.

“Mrs. Sullivan,” one officer nodded. “Sir.” He looked at Kevin, then at Tiffany. “We’re just here to keep the peace.”

“Peace,” I said, “is the new house rule.”

It took exactly forty-eight hours for the social ecosystem that had fed Tiffany to stop offering her snacks. Alejandro moved his family into a rented Airbnb two streets over for what he called “a proper Christmas with proper expectations.” He did not invite Tiffany. He did, however, invite me to coffee.

“You remind me of my aunt,” he said, stirring sugar into something so small it could only be ceremonial. “She set tables for everyone until one day she decided to let everyone set their own. She wasn’t loved for a while. Then she was respected.”

“I will take the second,” I said. “Love can visit.”

On Christmas Day, the house smelled different. Not like last-minute delivery but like something alive. When you cook under duress, you oversalt or undersalt; you season with anxiety instead of memory. When you cook because you want to eat, you remember to put your hand over the steam and inhale first. We ate simple food: roasted chicken instead of turkey, potatoes that knew honest butter, citrus salad because I like to feel summer at my table in winter. Alejandro brought Cuban coffee so strong it made the spoons stand up.

We set the table with my everyday china. Not because the good dishes weren’t worthy, but because ceremony and respect are not the same thing. I put the good tablecloth away deliberately; you don’t reward returned respect with silk. Cotton washes better and holds the smell of conversation.

We went for a walk after lunch. Some of Tiffany’s cousins waved from the rental’s porch with the sort of guilty affection people feel when they’ve swallowed a lie you’ve finally spit out for them. A child with antlers on a headband told me my wreath was “old-lady pretty,” which I decided to accept as a generational compliment.

Late that afternoon, Kevin knocked on my door. He’d shaved. He looked twelve.

“Can I… come in?” he asked.

“Shoes,” I said, because even remorse can track dirt.

He sat, hands on his knees. “Alejandro says Tiffany will have to go back with him for a while. Pay back what she borrowed. Get a job that actually exists.”

“Good,” I said.

“I told her I’d go with her. Help her. If she does the work.”

“Also good,” I said, and he looked relieved and not. “There are conditions.”

He waited, eyes on mine the way he had done when he was five and had broken something expensive with his joy. “You will not move out of town while you still owe me apology in actions,” I said. “You will not mortgage this house in your imagination. You will not invite me to parties as ‘help.’ You will learn how to roast a chicken by Easter.”

He nodded like a man writing a recipe in his head. “And Tiffany?” he asked, small.

“She will not cross this threshold until she can name three things she admires about the woman who cooked for her for five years,” I answered. “And she will mean them.”

We sat a while without words. Words can bruise when thrown too soon. He stood to leave and then turned, boy again. “Mom… I’m sorry,” he said. “Not just for Christmas. For the years.”

“I know,” I said, and I did.

That night, I took a bath with oils the spa had sent me home with, a thank-you for being the rare woman who tipped the masseuse like she tipped the bellhop—like both were doing work that preserved your back. In the morning, I stood in the garden with a cup of coffee and a coat over pajamas that had cost too much and were therefore necessary. A cardinal knocked itself into the window, then righted and flew to the cedar, red against a sky that would not choose a color.

The doorbell rang. I dried my hands on a towel. Valyria stood on my porch with a container of arroz con leche and an apology for the way her family had believed whatever was easiest to host. We ate out of the container with spoons. “It takes a lot,” she said, “to teach a whole room how to share.”

“Good thing,” I said, “I have time.”

On New Year’s Eve, I drove to the hotel where I had spent those first days of freedom and left an envelope for the housekeeping staff with a note: For the people who make rooms feel like rest. Thank you. On New Year’s Day, I met with my lawyer to sign the final trust documents: the house would remain a home in my name until I was done with it, and then in the name of a fund that would rent it at cost to a family who had cooked and cleaned for others until they could finally afford a kitchen that waited for them.

Somewhere in there, Tiffany texted a photo of her making scrambled eggs with a caption that said simply, learning. I sent back a link to a cleaning tutorial and the words, good—do the dishes too. She replied with a photo of a sink full of suds and, I grudgingly admit, a decent apology. She will have to write a better one. Words that cost people money are the only apologies that hold their shape.

By the time the wise men arrived in the calendar’s story, my house had a calendar of its own: Tuesdays my yoga mat on the rug; Thursdays the gardening club in my yard; Sundays coffee for whoever wanted to talk about budgets the way I can now—without fear, without hiding. Alejandro stopped by to bring a plant that looked like it had opinions. “For your porch,” he said. “It likes boundaries. You have those now.”

“I do,” I said. I watered it anyway.

You find out the oddest things when you set down your apron. For instance: holiday music is unbearable if you are resentful and oddly lovely when you are powerful. For another: Christmas is not a performance one woman puts on while everyone else narrates. It is a meal a woman can choose to attend or not, a tradition that survives being told the truth, a table that should hold chores as well as candles.

My phone chimed with a message from a number I didn’t recognize. Ms. Margaret—it’s the caterer you spoke to in June about your church fundraiser. If you ever want a quote for private events… I stared at it a moment and then laughed until my cat came to see if I was okay. I typed back, Thank you! I will call when I decide to host. For now, we’re all learning to cook for ourselves.

I’m traveling next Christmas. The trip is already booked. A little casita by the sea with a kitchen I won’t mind leaving clean every morning because the only person to dirty it will be me. Kevin and Tiffany’s tree will go up a week early or a week late, and may the lights tangle and untangle exactly as they deserve. Alejandro will read from the Bible before dinner because men like to anchor the room with words when women have already anchored it with casseroles. Someone will burn the rolls and everyone will eat them anyway.

It will be perfect. I won’t be there. They can handle it.

And if they can’t? They will learn. That’s all any of this was about in the end—what we are finally willing to learn when the person we thought would save us packs a suitcase and reminds us of the simplest truth: It’s my house. And, more importantly, It’s my life.

My Daughter-In-Law And Her 25 Relatives Are Coming For Christmas? Perfect — I’m Traveling. They Can…

Part Two

The house felt different after the papers were signed—quieter, as if the walls themselves had finally exhaled. My attorney left; the officers and the inspector left; the relatives lingered like steam after a hard boil. No one rushed to fill the silence with platitudes. It was as if the family had been playing a song on a badly tuned piano for years and someone had finally closed the lid.

Alejandro was the first to move. He tapped two fingers against the edge of the counter, then spoke in Spanish that needed no translation. “Comemos después, hablamos ahora.” We’ll eat later, we talk now.

He led the way to the dining room, not because ceremony was required but because the table was long enough to hold everyone and their stories. I didn’t take my usual place at the head; I took one end seat, with a glass of water and a pad of paper. I’d spent years setting this table for other people’s expectations. Today I set it for boundaries.

“Tiffany,” he began, voice calm as a pilot’s in turbulence, “start where the truth begins, not where the excuses do.”

Her voice was tinny without the usual Instagram filter. “I just wanted—” She stopped, caught sight of my gaze, and tried again. “I wanted my family to be proud of the life I built.”

“No,” Valyria said softly. She had a way of making correction sound like care. “You wanted them to be proud of a life you borrowed.”

Tiffany swallowed. “I thought if I made it perfect once, it would… stick. Like a sticker. Like it would not peel up at the edges if I pressed harder.”

“And the money?” Alejandro’s eyebrows made quiet questions without lifting.

She glanced at Kevin then back at her papers. “I spent what I didn’t have to keep up with people who didn’t care. I told myself it was temporary, that Kevin’s promotion was around the corner, that a bonus would cover the cards. I told his family we were fine because we should have been. And I kept telling the story until it was bigger than the truth.”

“Who taught you that story?” I asked. Not accusatory. Curious the way you get when you’ve also believed your own lies for a while: the lie that martyrdom is love; the lie that silence is peace.

“No one,” she said, then hesitated. “Everyone. It’s what you do on the internet. You post the best and spray the worst with room freshener.” She scrubbed at her eyes. “Also I grew up watching my mother say yes to the loudest person in the room. It made me think yes was the only way to be loved.”

“And here we are,” I said, “learning the power of no.”

We set to work. There is nothing like the smell of reality settling into a room.

Marco pushed Tiffany’s file across the table and opened a notebook. “We call in the loans,” he said. “No wiggle space. Family first does not mean family forgives theft. You’ll repay in installments—realistic, not performative. We’ll set a fixed timeline. Miss one, and the next step is legal.”

“I can’t—” Tiffany began.

“You can,” Alejandro cut in, gentler than his words. “You’re not the first person to owe the people who love her. Plenty of us owe, every day, and we pay by showing up.

“And to show up,” Valyria said, “you will need income that exists.” She slid a printed job listing across the table. “My firm has an opening for an entry-level operations assistant. You can apply. It’s not glamorous. It is real. It comes with direct deposit and a retirement plan. We will not ask your mother-in-law for references. We will ask to see you on time.”

Tiffany stared at the posting as if the letters might rearrange themselves into a position with a better view. “I… don’t know spreadsheets,” she admitted. It sounded like a confession.

“You’ll learn,” said Valyria. “And we’ll learn how to live without being lied to. Growth is cyclical.”

I stayed quiet and wrote a number on my pad—the sum of the loans, the price of the grocery store run that wasn’t, the cost of five years’ worth of apologies never made. Then I crossed out the grocery line; it felt petty when set against the larger math. I boxed the number and slid it to Marco. “Add interest,” I told him, “the kind compounded by inconvenience and the hours of my life I cannot get back.” He added ten percent, then paused. “No interest for the first three months if she keeps a documented budget,” he said. “Incentive matters more than punishment.”

“For the record,” someone said dryly, “we’re still hungry.” It was Evelyn, smiling tiredly. A cluster of the younger cousins had drifted to the doorway like moths. They’d been the ones loading and unloading grocery bags in a panic the day before, shocked to learn the difference between content and content creation. “We ordered buffet trays. Not fancy. Enough.”

“Good,” I said. “You’ll find my everyday plates in the lower cupboard. Paper towels are in the drawer to the left. Use both.” The simple directive landed like a reset switch.

We ate with the weird relief that follows an honest fight. The trays steamed; the nephews argued over which roll was the biggest; a toddler threw peas and was not corrected because loose peas on hardwood were the least of our concerns. We passed food without commentary and, near the end, someone started laughing at nothing in particular. Laughter is sometimes grief that found a back door.

That night was quieter than any I’d hosted in years. When people cleaned up, they put things away where they had found them. They scrubbed pans instead of soaking them for an imaginary cleaning service to discover later. They wiped their own fingerprints off my refrigerator with dishcloths that knew work.

Tiffany came to find me before bed with a folded paper. “What is it?” I asked.

“A letter,” she said, “and two envelopes. The letter is for you. The envelopes are for my cousins. I will hand them both out tomorrow when we discuss the loans—the apology you asked me to make in words that cost something.”

She set them down on the table and looked at me as if waiting for a grade.

“I’ll read mine later,” I said. “And I’ll decide if it belongs in a keepsake box or the shredder.” She flinched, then nodded.

“Will you come back for Christmas dinner?” she asked, almost a whisper. “I mean, the second one,” she added quickly, “the one we will have when we are ready—maybe it will be in March, but we can still call it Christmas.” She tried for a laugh and almost made it. “I’ll make… something.”

“I already had Christmas,” I said. “It happened this morning.” Her face crumpled and smoothed again. “Easter, then.” She rallied. “Kevin says he’s learning to roast chicken by Easter.”

“Easter is ambitious,” I said. “Ambition is good.”

January arrived with salt on sidewalks and lists on my refrigerator. The residency agreement hung in a frame by the door like a poem. It looked beautiful, not because it had calligraphy but because it had consequences. On Tuesdays, the gardening club started coming; on Thursdays, I taught a small class called “How To Not Weaponize Hospitality” for three women from church and two cousins who wanted to learn where the mop lives. We laughed more than we cried.

Kevin texted a photo on the second Saturday: five ingredients lined up like suspects—chicken, lemons, rosemary, potatoes, salt. Assignment commenced he captioned it. Ninety minutes later, I received a second photo: a bird with slightly singed legs and a pan sauce that looked suspiciously like dishwater. Edible? he wrote.

I called. “Did you let the chicken come to room temperature before roasting?” I asked. “Did you pat it dry? Did you salt it like you mean it?” Silence. The sound of a man Googling. “Start again next week,” I said. “You get good at what you repeat.”

Tiffany took the operations job. The first week, she texted me a photo of her desk: a plant, a cheap notebook, a mug with the company logo, and a spreadsheet on her screen. The second week, she texted me at seven-thirty in the morning asking whether “sum” was a verb and why budgets were so… judgey. I sent a link to a free Excel course and a thumbs-up emoji that even my cat would have read as maternal.

By Valentine’s Day, she had paid the first installment on the family loans. It was accompanied by the apology letters she had promised to read out loud at Alejandro’s kitchen table. “I’m sorry for using your money to buy strangers’ approval,” one line said, and when she looked up after reading it, no one rushed to pat her hand. It is important to leave apologies standing on their own legs for a while.

As for me, I did what women do when there’s finally air in the room: I remembered a passion I’d stored in a box labeled “later.” The front bedroom, once the guest room, became my studio: drop cloths, a sturdy table, sunlight arranged like a generous hostess. The first time I squeezed paint onto a palette, I cried a little. It felt like learning to eat after being too polite for too long.

Spring turned the yard soft again. I taught two of the cousins how to prune roses without severing either the branch or their patience. The youngest, a girl with a headband full of daisies, asked me why grownups gave the best parts of their day to people who didn’t deserve them.

“Habit,” I said. “Fear.” I reached up and pinched off a spent bloom. “And hope that if we keep feeding, one day we’ll be invited to the table. Turns out you can just sit down.”

Easter arrived like a pop quiz and Kevin passed. The chicken was golden. The potatoes were crisp. He sliced into the thigh and didn’t look terrified. We ate at their little table under a crooked print of their wedding photo, and Tiffany served a lemon tart that tasted like she had learned to respect the recipe’s math.

“Happy Easter,” I said, and meant it.

Summer became a series of small repairs. Tiffany repaid another slice of debt and started bringing her own dish to any gathering without being asked. She stopped using the word “help” like a weapon. She did relapse once—she posted a “hosting hack” that was a photo of my lasagna with a Pinterest filter—but when I sent her a screenshot with just a period, she took it down and posted a photo of her sink instead, captioned, The real hack is soap.

In September, Alejandro and Valyria invited me to Miami for a week. We ate pastelitos and drank coffee that made conversation faster. Tiffany came for the weekend. She helped in the kitchen and did not narrate it. She sat on the patio with me one night after everyone else had gone to bed, the air humming with cicadas and forgiveness.

“I don’t know how to be someone you like,” she admitted, barefoot with a throw over her knees. “But I know how to be someone you can live with. I’m trying.”

“I see that,” I said. “And I see you.” I reached over and squeezed her hand. “For what it’s worth, I don’t always know how to be someone I like, either. I’m trying too.”

By Thanksgiving, we had new traditions with fewer platters and more chairs—actual chairs for actual people who had done actual work that day. We made a pie chart, literally, of duties. We wrote names next to slices: prep, cook, clean, host, rest. “Rest?” one cousin asked, delighted. “It’s a job now?”

“It’s a job,” I confirmed. “Do it well.”

I booked my next Christmas in September. Not Miami. Madeira. I wanted cliffs that made you respect gravity and a hotel that called me Dona when I checked in. I printed the itinerary and stuck it to my refrigerator with a magnet shaped like a rooster. When Kevin saw it a month later, he laughed, relief heavy and happy. “Perfect,” he said. “You’re traveling.”

“Correct,” I said. “You can handle it.”

He grinned. “We can handle it.”

Christmas Eve arrived with flurries and a clean kitchen. I set up a video call with Alejandro’s rental and watched chaos that was not mine. There were lists taped to the walls and flour on Valyria’s shoulder and a stack of paper plates that did not aspire to be china. Tiffany appeared on screen with her hair pulled back and a baby on her hip—her sister’s, on loan. She winked. “We made the potatoes ahead,” she said. “Reheating avoids drama.”

“Good,” I said. “That’s how civilization advances.”

Kevin angled the phone toward the stove. He had three burners going and a roast resting. He had on an apron that said, I did this without Margaret. It was a joke; it was the truth.

“Show me your sink,” I commanded. He turned the camera. Empty. He cleared his throat. “We clean as we go now,” he said. “You were right—the mess isn’t a medal.”

Alejandro leaned into frame. “Mrs. Margaret, I want to report something.”

“Oh?” I said. “Is it food poisoning?”

“No.” He set a hand on Tiffany’s shoulder. “It’s gratitude.” He looked into the camera. “We will never talk about you as help again. We will talk about you as teacher.”

“Teacher is fine,” I said. “Student is better.”

We hung up when their doorbell rang—cousins with too many coats and not enough sense about where to put them. My own door stayed quiet. I made myself a small dinner: an omelet so buttery it did not need cheese, a salad with the last good tomatoes, a slice of the lemon tart I’d frozen from Easter because celebration resists calendars. I ate on my couch with my feet tucked under the good blanket and thought about how remarkable it was to feel full in the middle of December without having first emptied myself to feed everyone else.

The sea below my balcony in Madeira was the color of honesty. On Christmas morning, I took my coffee outside and watched waves argue with rocks, the way stubborn things do when they both have a point. My phone pinged: a photo from my dining room. It was at an angle—whoever took it hadn’t thought about symmetry, and bless them for it. The table was mismatched and beautiful. In the center was a thrift-store vase of clementines. No one was posting it for likes. They were just sending it to me so I could see what we’d built.

“Perfect,” the caption read. “You’re traveling. We’re handling it.”

I wrote back, “Love to everyone. Save me a roll.” Then I put my phone face down, picked up my book, and felt my life fit me.

When I get home in January, the house will smell like winter and lemon oil. There will be a note on my counter from Tiffany saying the rosemary survived the cold because she covered it like I taught her. There will be an itemized list of loan payments complete with dates and confirmation numbers. There will be a new chore magnet on the refrigerator shaped like a chicken, with roast written in Kevin’s block letters and rest written in mine. There will be a line through maid on a scrap of paper and above it, in my handwriting, matriarch.

The thing about teaching people how to treat you is that you will be tempted to teach gently forever. You do not have to. Sometimes you can skip class and let the lesson come with paper plates and pizza and a family intervention that hiccups and then finds its breath. Sometimes you can book a flight.

Next Christmas, I plan to be somewhere with cliffs again. They remind you that the ground is not guaranteed. It is earned, step by step, with good shoes and better judgment. If Tiffany invites twenty-five relatives while I’m gone, perfect. I’m traveling. They can handle it. And if they can’t, there are catering menus and dishcloths and consequences. Hope is not a plan; a plan is a plan.

I am Margaret. I am 66. I am not the maid. I set my house in order. Then I set my suitcase by the door.

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load