My Daughter Got $33M And Threw Me Out — 3 Days Later, She Was Begging For My Help

Part One

I was still learning how quiet a house can be when one half of a marriage goes missing. The kettle clicked off; the clean, contained sigh of steam had no one to answer it. Robert’s slippers were exactly where I’d left them the night the ambulance took him—a gap on the rug just big enough for my grief to keep tripping on. Forty-three years of marriage makes a landscape, and widowhood redrew the map overnight.

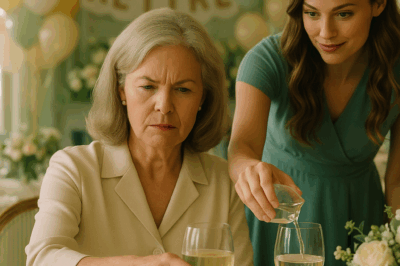

Victoria arrived with sympathy wrapped in silk. “Mom, this place is too big for you now,” she said, moving through the rooms like an appraiser, not a daughter. Kevin stood in the doorway, checking his watch, the way you check weather you think won’t change. They brought glossy brochures for retirement communities I hadn’t asked to see and said words like activities and independence as if walking me to the door of my life could be spun as a favor.

I should have paid more attention to the gleam in her eye. I should have remembered that Victoria had always been tender where tenderness served her and steel when it did not. Robert loved her in the way fathers sometimes love daughters they see themselves in—the way kings love heirs. I loved her the way mothers love daughters whose sharp edges you learn to navigate with a thousand small detours.

Six weeks after the funeral, she came without calling because that’s how people arrive when they believe what you have already belongs to them. Kevin set two suitcases by the front door as if my home were a hotel. Victoria sat me at the kitchen table where I had ironed her school uniforms, iced all her birthday cakes, mended all the tears she never meant. She laid a stack of papers between the salt and the pepper like an altar.

“We’ve made a decision,” she said. “Kevin’s promotion means we need to be closer to the city. This house is perfect for us.”

I blinked at her, the words milling around the doorway of my comprehension, refusing to come in. “Move in? This is my home.”

“Actually,” she said, and the mask slipped just enough to show me the blade beneath, “Dad left everything to me. The house, the accounts, all of it. I’ve been letting you stay out of kindness, but it’s time for you to find your own place.”

I felt the floor tilt. “That’s not… Robert wouldn’t—”

“Mom.” She leaned forward, softening her voice the way you soften butter: not for its sake but to make it easier to spread. “He knew I’d take better care of his legacy. You never understood investments. You were just the wife.”

Just the wife. Forty-three years reduced to three words that tasted like pennies in my mouth.

She didn’t say please leave. She said, “Find somewhere else to die,” as if she were giving me permission to choose the scenery.

Kevin carried my suitcases down the front steps, one in each hand, efficient as a bellhop who hopes for a tip. He didn’t meet my eye. He didn’t have to. He’d already done whatever looking he intended to do at me years ago.

They booked me a room at the Sunset Inn, where the carpets have lived several lives and the towels belong to forgetfulness. Victoria pressed two hundred dollars into my hand like a tip and said, “We’ll transfer some money once we sort Dad’s paperwork.” Then she left me on a sagging mattress with a view of the parking lot and a television bolted to a dresser that had more dents than dignity.

Grief makes you foggy, but it doesn’t make you stupid. Robert had shown me his will. He was fussy about such things—copies in labeled folders, original in the safe, old versions crossed through with lines so neat my eyes would water. He had not been a cruel man. He had been particular and proud and occasionally patronizing about money. He had not been the sort who would leave me with nowhere to sit down in the country he built.

In the morning, I took a bus to the law office where we’d signed our first mortgage. The secretary looked startled to see me; the attorney, Harrison Fitzgerald, looked relieved. “Margaret! I’ve been trying to reach you. Victoria said you were traveling.”

“Traveling,” I repeated. As euphemisms go, it was almost charming.

He fetched a file the size of a telephone book and set it on the table with both hands. “I gave Victoria the original will and several certified copies the day we read it,” he said. “The day we read it,” he added, and his voice softened. “You were supposed to be there.”

He read aloud, and the world I had lived in until yesterday knitted itself back together as if someone had picked up all the dropped stitches. The house. Seventy percent of every account. Specific bequests to friends and charities I loved. And then: a trust for Victoria—ten million dollars—subject to a clause that made me catch my breath: contingent upon her treatment of my beloved wife following my death.

Harrison looked up at me over his glasses. “Robert was worried,” he said simply. “He updated the will six months ago.”

I closed my eyes, saw Robert at his desk, pen uncapped, licking his finger to turn the page the way he’d always done. He had not been cruel. He had been careful.

“What she’s done,” Harrison said, his voice all soft fury now, “is fraud. Elder abuse. Theft. She forged something or presented an old draft. We’ll call the bank. We’ll freeze everything. We’ll call Detective Rodriguez, who has a good nose for the sort of thing that happens when grief sits down at a table with greed.”

The plan unfolded with the quiet competence of a machine designed by someone who had been alive longer than my daughter had been arrogant. Accounts were frozen. Utilities suspended pending ownership verification. A detective with kind eyes and a cop’s posture asked if I had anywhere safe to stay; I told her about the Sunset Inn and she pressed her lips together in a way that said not anymore.

My phone, which had been a monument to silence, lit up with spooked birds: texts from Victoria—Mom? The bank says Dad’s accounts are frozen. There’s a mistake—calls from Kevin—Let’s be reasonable, which is what men say when your reason is finally stronger than their convenience. I told both of them the same thing: speak to Detective Rodriguez. Speak to Harrison. Speak to the truth. Then I turned off my phone and slept in my own bed for the first time in six weeks.

I should have felt triumphant. I felt unsteady. Forty-three years as a wife makes you good at one particular balance: keeping your footing while a man moves through the house like weather. Being thrown out makes your feet forget. Being restored makes your feet doubt.

The arrests came faster than I expected. The evidence of the forged will, of the forged signatures on authorization forms, of the forged everything filled a conference room. A printer I had never loved more spat out proof at a speed that made my heart race. Victoria was handcuffed in the scented air of a restaurant where she’d gone to celebrate her new life; Kevin was led away from a desk covered in deals that would not be made by him anymore.

Three days from the night she told me to find somewhere else to die, my daughter sat on my porch with mascara pooling in the hollow beneath each eye. “Mom, please,” she said. “Think about the grandchildren. Think about what this will look like.”

“Three days ago,” I said, “you thought about none of those things.”

“Daddy would never—”

“Daddy,” I said, “recorded a message to be played if you did exactly what you did.” I pressed play. Robert’s voice was steady even from the grave, as if death had not loosened him an inch. If you’re hearing this, Victoria, it means I wasn’t wrong to worry.

She listened and folded in on herself the way houses fold when storms come through.

“What happens now?” she asked when the recording ended.

“Now you beg for help,” I said, not unkind. “Now you understand that help comes with conditions.”

And then came the twist I had not expected and the old life I thought I knew tilted again.

Harrison called while I was making coffee. “Margaret,” he said, “my office received a letter from Kevin’s attorney. They have… information. The sort used as a lever.”

“What sort?” I asked, knowing and not wanting to know.

“The sort that suggests Robert’s business wasn’t as clean as his desk.”

I was halfway to telling Harrison that Kevin was bluffing when the doorbell rang and Kevin’s mother, a woman made of pearls and certainty, swept in to explain why my moral clarity would be so much more comfortable if it came with a settlement. “Five million and the house,” she said. “We make the unpleasantness go away. You keep your… dignity.”

I thought of Victoria’s words—just the wife—and the way women like Eleanor make wives invisible by calling their survival dignity. I smiled the way women smile when they have something sharp behind their teeth. “No.”

The next morning, I sat in a federal conference room across from a woman who introduced herself as Agent Sarah Martinez. She had the look of someone who is paid to get to the part where the truth stops flinching: neat hair, neat notes, neat line between this matters and that can wait. I told her everything: the forged will, the Sunset Inn, the porch, the recording. When I finished, she slid a file toward me and said a sentence that made me grip the edge of the table to keep from falling off the world.

“Mrs. Sullivan,” she said, “your husband was an FBI informant for twelve years.”

I looked at the words CONFIDENTIAL COOPERATING INDIVIDUAL and saw Robert again at that desk, pen uncapped, doing the thing he did when a problem needed a shape: make a list, make a plan, make a call. He had been laundering money, yes. He had been laundering it for the Bureau. The money I thought might be poison was, perversely, clean; earned for the work he had done to help put bad men in prison.

Agent Martinez asked if I’d wear a wire.

“Will it make me feel like a character in a television show?” I asked, because sometimes humor is the only lever you have to lift your fear.

“You’ll feel like a woman who didn’t let other people write the last chapter,” she said.

Three days after the porch, three days after the motel, three days after my daughter told me to die somewhere convenient, I invited her and Kevin into my living room and let them try to sell me my own safety. When they finished their pitch, Agents came through the door as if my house had grown a conscience with feet. Cuffs clicked. Kevin said, “You don’t know the people Robert dealt with,” which was a threat dressed as a warning, and Agent Martinez added a charge to the list with the kind of efficiency that makes justice feel briefly like a well-oiled machine.

In the quiet that followed, I made tea. It felt important to steep something ordinary.

I slept through the night for the first time since the funeral.

Part Two

My lawyer, my detective, and the FBI all agreed on one thing: the hardest work was done and the most dangerous work had just begun. Money is not a thing so much as a system; systems are vindictive when you try to unbuild them. Agent Martinez met me in my study with a map of my life spread on the desk: returns to file, banks to re-verify, passwords to reset, names to forget.

“Do you want to keep the house?” she asked. “We can sell it, move you, make you harder to find.”

I looked at the doorway Victoria had walked through to tell me to find somewhere else to die. I looked at the window Robert had measured and re-measured before allowing blue curtains instead of beige. “Yes,” I said. “I do.” Some wars are won by staying.

The media found us anyway. Nobody is as interested in a living old woman as they are in a dead one until the old woman refuses to stay dead and drags her would-be heirs into court by their perfect hair. My mailbox filled with letters that smelled like lavender and regret. Women I’d never met wrote, “Your story is mine,” and enclosed snapshots of grandchildren I wasn’t related to as proof their daughters had done at least one thing right. A local reporter asked the question none of the men had thought to ask: what would happen if widowhood came with a script that didn’t include surrender? That segment went viral. That question stayed with me.

Victoria called from jail the way children call from summer camp when the night noises are louder than the stories they told. “Mom,” she said, and for a second she was six and had dropped her ice cream.

“I’m listening,” I said.

“I need your help.”

“I know,” I said. “I know.”

“I’m sorry,” she blurted, the words crashing into one another, all corners and no cushion. “I’m sorry I said those things. I’m sorry I did— Mom, please.”

I closed my eyes. The three-day mark—three days after her eviction of me—had been perfect for begging: not enough time to develop insight, just enough time to develop need. “Victoria,” I said, opening my eyes so I would not say what wasn’t true, “I will not interfere with the law on your behalf. I will not endorse a paper that harms a stranger to save my own. I will, however, meet with your lawyer and tell them what the FBI told me: that the money in my accounts is clean, that your father was a cooperating witness, that your attempt to blackmail me with dirty money failed because it wasn’t dirty.”

“I didn’t know,” she whispered, and I believed her.

“You didn’t ask,” I said, and she knew I was right.

We met in a small room at the detention center where the air smelled like bleach and apology. Her attorney looked like every lawyer on television except for his eyes, which were tired. I told them the truth and asked for some from them in return. “What were you paid to forge?” I asked Kevin’s name without looking for him, because I had promised myself not to say it when I did not have to.

“Signatures,” she whispered. “Letters. The printed copy of an old will with a new date. He said… he said you’d never know. That you wouldn’t fight.”

“I raised you,” I said. “I know who taught you to count on women giving up.”

After the meeting, I walked out into a day bright enough to hurt. Harrison sat on my front step with a file folder and a tin of shortbread. “For your nerves,” he said, handing me the tin. “And for your empire,” he added, tapping the folder.

Inside: the deeds in Robert’s precise hand, the trust paperwork in Harrison’s steady print, an updated set of everything with my name where his had been. Along with them, a letter in Robert’s voice as blunt and careful as he had been. If anything happens to me, it read, and you discover everything, please remember: I never did anything I couldn’t explain to you. I’m sorry you have to find out this way. Please paint something with the money, and make a garden where I can smell the tomatoes even if I can’t eat them.

I did both. I turned his study into a studio with windows that remembered how to open. I planted a garden that smelled like summer camp and soup. I kept a single file cabinet because you never stop being a wife to a man who loved paperwork and because I had papers of my own now.

The day Victoria came home I did not go to the courthouse. I went to the garden and cut hydrangeas with a pair of shears sharp enough to make me feel careful. She arrived in a cardigan too thin for the weather and shoes too hopeful for the path. “Mom,” she said, standing on the walk, her hands empty because that was all she had to give me. “I’m… home? Can I say that?”

“You can say it,” I said. “Whether it is true will take longer to answer.”

She looked over my shoulder into the hallway where the new rug had replaced the old one that had for years caught all the mud we tracked in from the life we’d made. “I don’t know how to be in this house with you now,” she admitted.

“Start by taking off your shoes,” I said. “Then come sit at the table like a person who might learn something.”

We set out two cups and one teapot like a hospitality lesson. “I’m here to listen,” she said.

“I’m here to speak,” I replied, and we both nodded because we’d finally applied for the right jobs.

I didn’t punish. I didn’t console. I taught. It turns out that after forty-three years of allocating time and attention and energy to other people’s hopes, a woman becomes a very good instructor. I showed her the ledger where choices had balances. I showed her the garden where consequences took root. I showed her the bank statements where her name had once been and how easily it disappears when the math changes. We went slowly. We went over. We went under. We did not go back.

Kevin did not come home. He wrote me a letter instead, mostly excuses with a small square of remorse folded into a corner like a napkin. I wrote his mother, Eleanor, a note the length of a sentence. Do not contact me again unless it is to apologize for the day you threatened to ruin Robert’s name to save your son’s. She did not. She sent a bouquet two weeks later without a card. I composted it.

Money is loud when you don’t have it and invisible when you’ve always had it. Having it suddenly—cleanly, legally, legitimately—made me determined to spend it in ways that would make my grandchildren point to buildings and say, “Gran made that happen.” We set up the Sullivan Fund for Elder Protection, because names matter and so do lawsuits we can afford to file for people who can’t afford to lose. We wrote grants for clinics that promise no one signs alone. We underwrote a bill that makes exploiting your mother as expensive as it ought to be.

Netflix called. A producer with hair more expensive than my car asked if I’d be comfortable being portrayed by “someone like Meryl.” I told her Meryl would be lucky. We laughed. I wrote a clause into the contract that sent every cent of my fee straight to the Fund. The film team came for three days and left with a lot of footage of my hands shucking peas because they realized too late that villains are easier on camera than the women who survive them. The series, when it premiered, made a lot of people furious at their daughters. It also made a lot of daughters furious at their mothers. Good art does that.

On a Tuesday six months later, a girl from next door knocked on my door with a form for a school project. “What do you think it means to be powerful?” she asked, pencil ready.

“To have the time and money to be kind,” I said, and she wrote it down very carefully and underlined kind as if it were a vocabulary word that could be on a test.

Victoria brings the grandchildren on Sundays now. The first time, she hovered in the hallway like a woman waiting to be sized for more shame. I handed her the baby wipes and said, “If you’re here, you’re working,” and she laughed for the first time in too long. We make pancakes. She tells me about her meetings with other women who did bad things and are trying to build good lives on top of their pile of wrong. Sometimes she lights a candle for Robert without asking if she can. I let her. He taught me to make lists. She taught me to accept small offerings.

On the anniversary of the porch, we sat there together and drank lemonade. “Do you ever think about the exact moment you became someone else?” she asked, not looking at me.

“I think about the moment I stopped being the version of myself that made your life easier,” I said, and she flinched, which meant she had listened.

“Thank you for not letting me get away with it,” she said, and she meant the crime and the life. I didn’t say you’re welcome. I said, “Hand me the sugar, please,” because we love people better when we keep them in the present tense.

I have the house. I have the money. I have a foundation that sues people who say just the wife and win. I have a garden that refuses to care how it looks to anyone but the bees. I have a painting in the hall of a woman standing in her own light. It took a child’s betrayal, a husband’s hidden courage, and a federal agent’s competence to give me my own story. It shouldn’t require any of that. It did.

Three days after she threw me out, my daughter stood on my porch and asked for help. I gave her the only help that would honor us both: the truth, on paper and in cuffs. Months later, she asked again, and I gave her the only help that would make us family: a chair, a chore, a chance. There’s a difference between rescue and repair. You can survive one. You have to work for the other.

If you come looking for me, you will not find me in a motel. You’ll find me in my kitchen, leaning over a ledger that finally makes sense, or on my porch, teaching a grandchild to count lightning between thunder, or at a courthouse, watching a judge sign a law that puts a price on cruelty too high for anyone to pay without thinking twice. You’ll find me exactly where I decided to live the day I stopped being obedient.

And if you ask how it ends, I’ll point at the garden and say, “Like this.” It grows, because I tend it. It grows, because enough was planted before me. It grows, because the hands that tried to uproot me didn’t know how strong a woman’s roots are once she decides to keep her ground.

END!

News

At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses. CH2

At My Retirement Party, My Daughter In Law Slipped Something In My Drink — So I Switch Glasses. Part One…

“Grandma, My Parents Are Going To Take All Your Money,” My Granddaughter Said. Then I Made My Plan. CH2

“Grandma, My Parents Are Going To Take All Your Money,” My Granddaughter Said. Then I Made My Plan Part One…

At Midnight, My Stepfather Beat Me—My SOS Text Brought the Special Forces to My Rescue. CH2

At Midnight, My Stepfather Beat Me—My SOS Text Brought the Special Forces to My Rescue Part One I woke…

The Day Before Brother’s Wedding, When I Said ‘I Can’t Wait for Tomorrow,’ My Aunt Froze in Shock.. CH2

The Day Before Brother’s Wedding, When I Said “I Can’t Wait for Tomorrow,” My Aunt Froze in Shock… Part…

My Ex Married His Dream Woman Right After Our Divorce—Then I Saw Her Face And Knew Everything. CH2

My Ex Married His Dream Woman Right After Our Divorce—Then I Saw Her Face And Knew Everything Part One…

My Daughter-In-Law And Her 25 Relatives Are Coming For Christmas? Perfect — I’m Traveling. They Can… CH2

My Daughter-In-Law And Her 25 Relatives Are Coming For Christmas? Perfect — I’m Traveling. They Can… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load