My Daughter Excluded Me From Her Vacation—She Had No Idea I Own The Resort She Was Visiting

Part One

The message arrived at 2 a.m., the kind of hour when truth gets honest and dignity wears thin.

Mom, it read, I think it’s best if you don’t join us for the trip to Silver Palm next month. Amanda’s parents are coming and there isn’t enough room for everyone. I hope you understand. —Clare

Not enough room.

At Silver Palm.

The same Silver Palm whose three terraced infinity pools appear to fall into the Caribbean, whose villas were rebuilt beam by beam in white oak and hand-limed plaster. The same Silver Palm that quietly sits inside a holding company with my maiden name as its second initial. The resort I bought four years ago, poured twenty million and all my sense of beauty into, and ran from an office silence taught me to keep.

I set the phone face down on the quilt and watched the ceiling fan turn like a slow decision. I could reply with the truth: You’re vacationing in a place I own; there will be room for the moon if I say so. But the temptation to see what my daughter would say when she thought I was small—when she believed I would stay small—was stronger than the urge to end the story neatly. Patterns don’t break unless you trace them with a bright pen.

I typed: I understand. Have a wonderful time.

I didn’t sleep. Instead, I lay in the soft dark and replayed a life that once ran on clocks and grit.

For most of Clare’s childhood, I smelled like diner grease in the morning, disinfectant in the afternoon, and lemon oil at night. I stood ten hours on linoleum floors filling coffee and calling people “hon” with a softness they needed. I learned who tipped and who didn’t, who was newly sober and who had fallen off the wagon again. I folded pressed uniforms for the dental clinic, taught myself appointment scheduling software until I could run a four-chair practice with one eye on the daybook and one on a toddler coloring in the staff lounge. And on Saturdays I scrubbed other people’s kitchens until every chrome fixture threw back my face, raw-knuckled and alive.

I did not martyr myself. I bought Clare the braces that made her smile confident. I sold my mother’s antique silver so she could stand in front of the Lincoln Memorial with her eighth-grade class. I worked Christmas morning because triple pay would cover the semester’s books. Every choice had a name: rent, electric, tuition, orthodontist, ballet. My palms cracked and my back ached and there was joy inside that ache because it meant we stayed afloat.

It was the woman whose house I polished on Tuesdays that nudged the wheel. Beth had been a vice president somewhere with the kind of dry humor that made survival sound like a neat trick. One Tuesday she left a French press and a typed note: I’m investing in a medical software company. The team is strong. If you have anything you can put in, you should. She looked me in the eye when I arrived. “You remind me of me,” she said. “Just without the breaks. Let me be one.”

I did something that will sound either reckless or faithful. I took the small insurance payout my parents left me when they died—$7,200—and I bought a sliver of that software company. I did not mention it to Clare. I did not expect anything. Then I went back to the daybook and the rinse-and-vac and the lemon oil.

Three years later the company got bought. My sliver turned into a slab, then grew again when I followed a careful man’s careful advice and kept half in the new parent company stock. I learned what dividends tasted like. I learned how portfolios are gardens if you stand in the right sun. I learned, most importantly, that my fear of losing everything needed new management.

By the time I walked into a tiny lawyer’s office and signed documents to create a quiet hospitality group, I could have shouted my news from the roof of our old building. But the part of me that had survived frozen nights with the heat turned down to “prudent” had developed other habits. I didn’t want to change the way people looked at me by changing the way I said me. I wanted to be sure that the woman I had been—the one with lemon oil under her nails and coffee in her bones—didn’t get trampled by a version wearing silk and talking in acronyms.

So I told Clare I’d found a better job at a friend’s business. I moved to a pretty condo and called it a good deal on a fixer. I bought three nice dresses that looked like six. And my daughter—my clever, beautiful, increasingly busy daughter—did not ask how I’d done any of it.

When her boyfriend became her husband, his mother became an orbit. Martha spoke like a woman who’d swallowed a manual and a country club menu, and she pronounced my name as if it had too many syllables to be convenient. “Customer service,” she repeated when she met me, pursing her mouth around the phrase the way people in glossy magazines smell cheeses. “How…salt of the earth.” Richard, her husband, had a soft voice made sharp with judgment disguised as concern. “We’re only trying to help Clare have the life she deserves.” Help looked like decisions made in rooms I was not invited into: rehearsal dinners scheduled during my shifts, guest lists calibrated to a calculus I did not understand, my seat gravitating toward a distant table.

When Clare and Greg moved into a pretty house with a mortgage that had a ridge of frost on it, I offered to help. He smiled and declined. Six months later he knocked on my door with a sheepish expression and a request not to tell Clare. “She worries,” he said. “This will ease her mind.” He brought me financial statements and a noble story about independence. I brought him a private mortgage at a better rate than any bank would give, and a paper trail as neat as the dental books I once kept. He promised—and I made him write it—that I could inspect the property and the books when I wanted. That promise turns out to be a plot point.

I told myself they were simply becoming themselves—their own household, their own rules. I told myself the distance had nothing to do with cashmere and Amalfi and the whiff of being managed like a sticky jar someone planned to replace with something cleaner. And maybe I half believed it until Christmas became we’re renovating and the ballet recital became oh, it was yesterday and a family vacation became no room in a resort whose penthouse was literally designed to sleep twelve because my imagination had built a future where it might be full of grandchildren.

So when my daughter texted I hope you understand, I decided to understand in person.

If you’ve never owned a resort, let me tell you what power looks like in linen. It’s not the grand gesture. It’s a raised eyebrow that means the bar buys in better rum. It’s knowing the pavers three centimeters apart under the torchlit path were set by a man who told you about his sister’s wedding while he worked. It’s management who know you by a name they’ll never say out loud if you ask them not to. It’s a butterfly sanctuary because you wanted children who visit to leave with something no souvenir shop can sell.

I arrived at Silver Palm under “Walsh”—my father’s surname, my camouflage—and sent for my managers. Gabriella, who ran the place the way conductors make orchestras behave; Marco, whose front desk charm translated into five languages and a sixth called de-escalation; Elena, who taught the children how creatures turn hunger into wings; Anton, who made food that occupied that perfect space where comfort and vision sit down together; and Dominic, who understood that vacation memories have a schedule and a soul.

“My daughter is checking in Thursday,” I told them. “She doesn’t know I own the resort. I want to keep it that way—for now.”

They glanced at each other. They did not ask why. Loyalty is a muscle. We exercise it here.

Thursday at 11:42 a.m., a car disgorged people who believe their name should arrive before they do. Martha, immaculate in white linen, and Richard in golf-world khaki; Greg, carrying seven-year-old Lily like a prop he wasn’t sure how to position; Clare, beautiful and harried; and an assistant with a portfolio and a face that said she believed other people’s time belonged to her employer.

From my lounge chair in a quiet corner of the open-air lobby, under sunglasses I did not need if you measured light and badly needed if you measured nerve, I watched. Marco did his welcome so well it might as well have been recorded and yet it felt like something he’d said just for them. Welcome. Champagne? Cool towel? We are honored you are here.

They were upgraded to the Hummingbird suite not because they asked but because I’d told Marco to put my daughter in the rooms I’d designed. Martha immediately tried to upgrade her assistant. Marco checked the screen. Gabriella made an almost imperceptible move with her hand. “Palmetto Bay is lovely,” he said. “We’ll send a shuttle. She’ll want the privacy,” and that was the end of that.

I heard what you might have heard, sitting close enough to a koi pond to seem purely ornamental.

“Thank God we didn’t let Mom book this,” Clare said, swiping at her phone. “She’d have us at some place with plastic chairs and a buffet.”

“If we’d let her recommend,” Martha corrected, arching an eyebrow at Richard the way she might twitch the reins of a horse. “Everything she touches says coupon.”

If my heart had been glass, it would have cracked right then. If it had been stone, it would have rolled back down the hill. But it was flesh—older, scarred, and elastic. I breathed in salt and plumeria and told the hurt to go for a walk and let the strategist sit down.

That afternoon Clare took beach yoga without recognizing the woman on the back mat. I held crane pose like a woman who has learned balance is fifty percent breath and fifty percent standing still when the world suggests you sway. After class the instructor invited her to a sunset session on the private beach. Maya mentioned, with a nod at me, that “one of our regulars” would be there too. Clare followed the form of politeness without seeing the subject; when she turned and recognized me my full name hung between us like a broken shell.

“What are you doing here?”

“Yoga,” I said, because sometimes telling the truth exactly is the only way to soften it.

“Don’t make a scene,” she whispered.

“I don’t need to,” I replied. “You’re imagining one.”

She moved her lips around the numbers most people think about when they try to assign value to a person. “This place is a thousand dollars a night. You were cleaning houses last year.”

Perhaps I smiled. “There’s a lot you don’t ask me,” I said. “And so a lot I haven’t had reason to tell you.”

We skated across politeness like people testing ice, then she rushed toward the refuge of we have dinner reservations and the conversation slid away.

That night I watched them at Azora: Martha editing the sommelier’s sentences; Richard performing discernment the way some men perform a back nine; Clare deferring, Greg imitating. Lily obeyed, quiet as a tired star. When Anton came to say hello, Martha sent back halibut that didn’t need sending back and ordered callaloo because she’d decided she wanted to be seen trying something local. “The owner must care about local,” she said. “But only when local is this good.”

When they laughed about my Olive Garden suggestion for a family celebration years ago, I remembered the waitress who’d slipped a free extra breadstick to a little girl who blinked up at her and the way that girl had fallen asleep in the car afterward, full and safe.

I left the restaurant with a plan that did not require a raised voice. If you want people to notice what’s real about you, put them in front of something that reveals what’s real about them.

The next morning the butterfly sanctuary welcomed Lily into its cool, green hush. Dominic arranged a “last-minute” upgrade to a private session. We watched blue morphos push themselves out of their jeweled sleep with effort that looked like fragility until you realized it was the opposite, and Dominic said the one line I’d asked him to include: “If you try to open their wings for them, they won’t be strong enough to fly.”

Lily asked the kind of questions teachers pray for. “Do butterflies ever get scared of falling?” —“They do, and then they fly anyway.” “Are moths butterflies with a secret?” —“Sometimes.” Clare listened and, for an hour, forgot to check her watch. When Dominic presented Lily with the friendship bracelet we give to the children who fall in love with the place, she lifted her arm like she’d been knighted. And when she asked if she could be a junior lepidopterist every morning for the rest of the trip, Clare’s eyes flicked to the corner of the ceiling where mothers look when they are calculating other people’s schedules, then—blessedly—back to her daughter’s face. “Yes.”

That was the first hairline crack.

The next was lunch in town, where my friend Maria runs a café that could teach entire economies how to be generous. Clare arrived in a sundress that looked like a vacation had decided to be a dress for the day. She drank hibiscus tea and asked questions without Martha within range. We talked. Not about money at first. About the years we’d both been quiet. About how hard it is to be the person you were when you’re sitting next to someone who tells you being that person is an embarrassment.

Then we talked about money.

“I looked up Reynolds Hospitality Group,” she said, as if she was confessing to checking a weather report and finding a storm. “The invisible owner. The one who never does interviews. That’s you.”

“It is,” I said.

“You invested—what? When?” The numbers tumbled out, incredulous, then stopped like birds that realize they’ve flown into the wrong room. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“How would it have changed what we had?” I asked. “Would you have invited me to dinner more? Would your jokes have landed softer? Would I have been the same mother to you if I’d arrived in silk? And would you have been the same daughter?”

She twisted her napkin as if she might strangle the embarrassment in its fibers. “We’ve been awful,” she whispered.

“You’ve been lost,” I said. “It happens in nice places too.”

When she asked if I was “testing” her, I shook my head. “Not grading. Watching. Hoping. And preparing to make peace with whatever I learned.”

Then we designed a dinner that would not let anyone pretend they hadn’t seen me: a private pavilion, a table with the ocean breathing beside it, a menu of childhood memories Anton plated like art. If confrontation is a dance, I wanted to choreograph it.

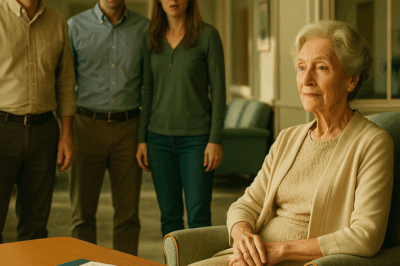

They walked in and found me waiting. Lily was delighted; Richard was curious; Greg did the mental math of a man trying to ladder new facts into his ambitions; Martha performed outrage; Clare performed nothing at all. She stared at a life she had failed to imagine and then did not blink.

I told them the truth, not all at once, but in courses. The investment. The fear. The choice to remain the woman who scrubbed counters even after she owned a room full of them. Martha sputtered about “deception,” and I asked her what she had told her son about kindness lately. Richard offered connections; I declined invitations disguised as opportunities. Greg wondered aloud if I would consider investors; I said I invested in people who could hold a napkin without snapping it at a server.

I asked Clare what she believed about herself when Martha wasn’t speaking for her. And when Lily—God bless straightforward small people—announced that “Families are supposed to love each other,” Martha finally stopped talking long enough to hear what hers sounded like.

We ate butterfly cake. We walked back through the torches like pilgrims who had not expected to find a shrine and did anyway. At the lobby, Clare asked me to lunch the next day—the first time she’d invited me to anything in years with no conditions attached—and I said yes like it was a new word.

That night Martha demanded a meeting. She arrived with Richard and her sense of offense pressed to a fine edge. Clare sat beside me, not at their side, and something old inside me stood up and breathed easy.

“Families grow apart,” Martha began.

“Families grow,” I corrected. “Apart is a choice.”

It wasn’t elegant. It wasn’t pretty. It didn’t end with hugs. It ended with Richard shepherding his wife to the elevator and Clare, who had been taught to keep sugar on her tongue, saying aloud: “I am going to my hometown with my mother and my daughter. You may send a card.”

That night we walked Lily through the butterfly sanctuary under lanterns, and I watched wings close and a child open. The next morning they ate breakfast on my terrace where the ocean pins the horizon like a promise, and Clare said words I’d waited far too long to hear: “I want to start over. Not pretend none of it happened. Start from where we are.”

I promised breakfast again someday in a kitchen where the coffee doesn’t smell like grease unless we decide we want it to for nostalgia’s sake. They left early, and I stood on my balcony and felt twenty years roll off my shoulders like a wet towel.

Perhaps you think that’s the end. It isn’t. Endings need agreements. And if you’ve ever negotiated with someone who believes they can rearrange reality by speaking sharply at it, you know that dinner under lanterns doesn’t fix character.

So when Martha sent a request to speak to “the owner” privately, I sent back: “Three o’clock. Bring your listening face.”

Then I called Elena to arrange a butterfly tea party at sunset with extra sugar cookies and more than one second chance.

Part Two

Three p.m. arrived on time and so did Martha’s fury, pressed into a linen sheath. Richard came, too. He is the kind of man who believes reasonable tone neutralizes unreasonable demands. Clare sat on my side of the desk and we were careful not to look triumphant because triumph isn’t the right flavor for new beginnings.

“You’ve orchestrated this humiliation,” Martha declared. “You could have told us. You should have told us. We would have accommodated.”

I folded my hands on the desk that had come out of a carpenter’s shop that smelled like planer shavings and pride. “You accommodated my daughter out of her mother,” I said. “You accommodated my granddaughter out of her wonder. I decided to accommodate the truth.”

Richard cut in. “What’s the endgame here, Eleanor?” He uses my full name like it’s a caution. “Bridge-building? Or a spectacle?”

“Neither,” I said. “A table. Pull up a chair or don’t. The table stays.”

Clare surprised me. “I’ve been letting you control too much,” she told them. “You taught me things I didn’t need, and I forgot things I did.” Her voice shook and then steadied. “I will bring Lily to the club if I feel like watching her pretend miniature golf is interesting. And I will bring her to my mother’s butterfly garden when I want to watch her eyes catch fire.”

Martha drew herself up. “You are throwing away opportunity.”

“I’m throwing away someone else’s idea of it,” Clare said. “We’re going home for a few days. When we come back, we’ll have dinner. You can decide then whether to be part of what comes next.”

Martha left, rigid and dangerous in the way people are when the story they tell themselves is interrupted. Richard paused and put a hand on the doorframe. “You’ve done well,” he said, an admission that tasted like rust in his mouth. “I didn’t imagine—”

“You didn’t look,” I said. “Try that next time.”

The rest of the day was logistics. We arranged a farewell sanctuary visit. We moved their checkout up by a day and sent their luggage to the airport with a note that said, Safe flight. We saved you a breakfast table. I stood by the lanterns that evening and watched Lily hold a moth as if it were a secret, and I watched a mother and a daughter stand close enough to each other to breathe the same air easy.

Morning breakfast was mango and things we’d laughed about the night before. I sent them to the airstrip with local bread and a jar of Maria’s jam, because beginnings get hungry quick.

Then I waited for the door to slam again.

It didn’t slam. It rapped—firm, official, foolish. Officer Ramirez stood in my foyer with paperwork balanced on embarrassment. “We received a report of possible elder abuse.”

I blinked. “You are standing in a home I paid for with money I made. You are speaking to a woman who could buy your department a fleet of cars and chose instead to buy her granddaughter a silver bracelet. The person who filed that report is attempting to cause harm.”

He believed me the moment he saw the way the books were balanced and the way my eyes were, too. He wrote his report and I texted Victoria to bring it to the next conversation.

The next conversation happened in a conference room at my mainland office with windows that make people tell the truth; I’ve seen it happen. Harold spread out papers like a dealer who knows which card matters most, and Victoria labeled tabs with a neatness that says No.

“Material misrepresentation,” she said, tapping a paragraph Weston had initialed with the vanity of a man who believes paper is suggestion. “We can accelerate the loan.”

“Do it,” I said.

“He’ll fight.”

“Let him get tired.”

“Meanwhile,” Harold added, “there’s smoke at his firm.”

“Let’s give that fire oxygen,” Victoria said, and smiled at a phone number only people who hate lying know. She called a friend at the SEC. The rest was procedure with sharp edges.

Weston met his future in a file folder and pretended it was a misunderstanding. He called the board of Emma’s nonprofit and made his lie bigger until it couldn’t fit in the room anymore. He forged. He threatened. He stepped into the role he had written for Emma without noticing the costume did not fit him.

We met him outside his office the day the subpoenas arrived. He tried “love” and “lawsuit” in that order. I told him disappear. I told him sign. I told him the truth has more stamina than a man who has never carried a bag heavier than his own ego.

He left town before the winter was over. I didn’t ask where. He is not my story anymore.

Emma moved back into her house when the peonies were planning their invention. We painted her bedroom a quiet lake and put a quilt her grandmother had stitched across the foot of the bed like permission. We had a housewarming that smelled like lasagna and cardamom and every woman who came brought a fork, a story, and the kind of laughter that doesn’t care where your chairs came from.

Then, because time is a circle when it’s given room, Thanksgiving came back. Emma asked if she could host. She invited Olivia and Marcus and their kids and me and no one else, and we volunteered at the shelter in the morning because that’s what you do when you remember what gratitude feels like in your hands.

We sat at her table. We passed dishes we made together. We listened to Lily talk about a painting she was making. We did not mention Martha. We didn’t need to. The air was easy.

After dessert I went out to the porch with a mug and the first cold to bite the tip of my nose. My phone showed me a message from Gabriella—the expansion at the Bise property was on schedule—and one from Maria—a picture of a pie that looked like a sunset. Then another buzz: a photo from Clare of Lily standing in front of my old apartment building, framed by the shell picture frame, her butterfly bracelet catching light like a small promise.

Learning where we came from, learning who we are, the caption read.

Inside, Emma’s voice rose above the rest. “Mom, you’re going to miss the cranberry if you stay out there judging the stars.”

“Coming,” I called, and I meant it—for everything that matters.

If you want the moral, here is mine: money didn’t save me. It made room for the parts of me that were already strong to take off their apron and stretch. The girl from the diner and the woman from the dental clinic and the housekeeper with raw knuckles—they are still in the room. They run my properties. They hire people who take pride. They notice when a guest’s eyes are sad and send coconut flan without asking who’s paying.

My daughter excluded me because she thought I would not belong. I did not correct her. I showed her. I let butterflies do their quiet teaching. I set a table. I spoke plainly. I did not apologize for what I had built.

She changed. I changed back into someone I recognize. There is work yet: memory has corners that need sweeping, habits have roots that trip. But we are sweeping, and we are looking where we step, and there is a granddaughter who knows that art is practical and science is wonder and families are the people who keep showing up.

And if anyone’s wondering—yes, there will always be room at my resort. For my family. For my daughter. For a child who knows how to hold a wing without damaging it. For anyone who believes in the right kind of second chances: the kind that require effort, and truth, and the strength that comes only when you do the hard part yourself.

END!

News

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call. CH2

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call …

BREAKING: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in America had dared to ask to do before. CH2

LATEST NEWS: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in…

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour. CH2

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour Part One I…

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments. CH2

When My Daughter-In-Law Said I Wasn’t Welcome For Christmas—I Canceled Their Mortgage Payments Part One It’s been said that family…

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About. CH2

My Daughter’s Husband Left Me at the Train Station With No Money—I Had Millions He Never Knew About Part One…

My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office. CH2

My Daughter Left Me at the Airport Gate, They Boarded—I Boarded My Private Jet to My Lawyer’s Office Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load