My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When…

Part One

The temperature seemed to drop twenty degrees in the restaurant the moment Morgan decided to be cruel.

We had barely sat down—one of those French places with brushed-silver cutlery that looks like jewelry and a wine list presented like a holy text—when she grazed my résumé with a smile. It never reached her eyes. “Marketing,” she said. “How… energetic. And from a single-parent family. My, my. How commendable that you’ve managed to accomplish anything at all.”

My fingers tightened on my water glass. Across from me, my mother straightened her spine. She had balanced trays and carried toddlers and held dying hands with that same posture. She’d done all three the day my father didn’t come home from the hospital. She was, to almost everyone, invisible.

“Being from a single-parent family,” Morgan continued, her tone syrupy as a liqueur and just as intoxicating to the unguarded, “life must be quite hard. Hm. Dating someone like you would be so complicated for Brian.” She shot her son a look so practiced I wondered if she kept it on a hanger. He nodded, lips tilting, confidence lacquered onto his face like varnish. He was handsome the way privilege makes men handsome: glossy, unworried, an heir to Sunrise Bank in loafers that probably cost more than my first phone bill.

“Presumptuous, isn’t it,” Richard added, leaning back with a proprietary air that said he owned not just the bank but oxygen, “for commoners to think they could marry into a family like ours.”

“Even if you try to bother us, it won’t hurt much,” Morgan said with a dismissive flick of her manicured fingers. “It would only be your money. Poor people with low backgrounds never cause real trouble.”

By the time the amuse-bouche arrived, every nearby table had learned our supposed station in the world.

I answered their disdain with an expression my mother taught me: nothing at all. You cannot be wounded by a blade you never grant the satisfaction of seeing your flesh. But when Brian cut in, his tone lazy with boredom, “I’m not really into strong-willed women,” something small and animal in me bared its teeth. I watched the waiter carefully place a quenelle of salmon mousse on my plate and imagined pressing my palm through it, just for the sensation of breaking something pretty.

“Did you invite us here to look down on us,” my mother asked quietly, “or did it happen by accident?”

Richard chuckled, head tipping back to display the flex of his jaw. “Please,” he said. “We’re just teasing. Learning the lay of the land.” He cocked his head, measuring us as if he were estimating a renovation. “No one really minds, do they?”

“No one likes being mocked,” my mother replied. “And we don’t intend to listen to it any further.”

Brian blinked, thrown off-balance by the firmness under her soft voice. Rich men expect anger; they are undone by dignity. For a moment, something crackled across his face—confusion, irritation—and then, as if flipping through a set of approved responses, he found his script. “Relax. Mom’s just being honest. If we’re going to be family, we should be able to say anything.”

“We’re not going to be family,” I said, lifting my glass and setting it down as if it weighed less than air.

Morgan smirked. “You think you can just—”

“I can,” I said. “And I am.” I folded my napkin with precise thumbs and laid it across the raw linen. “As for Sunrise Bank,” I added, because cruelty often arrives with opportunity, “you’re saying we should close our account with you, right? Please—by all means—go ahead.”

They laughed then. It was a sound I recognized from every high school cafeteria in the world. People who have never been cold laughing at the idea of winter.

“Useless attempt at drama,” Richard said, patting the table as if I had brought them a dog-and-pony show instead of the end of something. “We don’t even know your name on our books. How much could it be, really? A pittance.”

They returned to their plates, slicing duck breast as if carving into a world that had always accommodated their knives. I looked at my mother. She looked at me. In the space between our gazes, a thread tightened.

We finished the meal in a parody of politeness. I memorized the curve of Morgan’s mouth when the crème brûlée cracked under her spoon and filed it away under faces to avoid sharing oxygen with. When the bill came, I paid it. I wanted the record to show we left nothing behind that they could claim was owed.

In the taxi home, the city flexed in steel and reflected light. My mother turned her face to the window and murmured, “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t you dare apologize,” I said. I tipped my head back and watched the blur of signage pass. “They could have invited us to negotiate a boundary. Instead, they called us names. They think they can hold our dignity in escrow.”

My phone pulsed. A text from Brian: My parents can be intense. Don’t take it personally. Call you tomorrow?

I wrote back, Lose my number, and blocked his.

When we reached our apartment, a two-bedroom with sun in the mornings and a view of a maple that set itself on fire every October, I called my mother’s father.

“Grandpa,” I said when he answered, his voice warm silk even at nearly midnight, “it’s Natalie.”

“Natalie,” he replied, alert in a heartbeat. He always has been a man who keeps night watches for the people he loves. “What’s wrong?”

“Sunrise Bank,” I said. I didn’t have to explain beyond that. The pause on his end told me he had laid down a book and set his hand on something like a plan.

“What happened?” he asked.

I told him. I left out nothing. The appointment to humiliate us in public. The word commoners. Brian’s smirk. My mother’s quiet. Richard’s contempt. My own decision, made with the cold clean clarity that disgust sometimes grants, to pull the thread that held their world in place.

“They didn’t know who you were,” I finished.

“Most who wound strangers count on anonymity,” he said. “Come in the morning. Nine.”

I slept like I always sleep when I have a clean task to wake to: like I’m holding a list behind my eyelids.

In the morning, my mother wore her Sunday dress. She smoothed the front of it with both hands while we waited at the gate of my grandfather’s estate, a house that always felt less like wealth and more like a library that had decided to become a home. The guard waved us through the way he always had since I had been small enough to look from the backseat at the clipped hedges and whisper, castle.

In the study, my grandfather was all angles and silver—his suit, his hair, the lines around his eyes carved by a lifetime of reading contracts that were meant to mislead. He listened to my recording—the one I had started the moment we sat down in the restaurant because experience has taught me that men like Richard weaponize deniability and women like Morgan call you hysterical until you produce a transcript.

When the file ended with the clink of a coffee cup into a saucer, the room breathed. My grandfather didn’t. “We will handle this,” he said, his voice so calm it took me back to childhood nights on his porch when he would read me Moby-Dick and make the ocean sound like an office.

“Thank you,” my mother said. She wasn’t a woman who moved power brokers often. She had the sense to be quiet in the presence of one.

Two weeks later—two weeks of texts from Brian that ranged from injured to outraged to obliviously horny; two weeks of Sunrise Bank’s marketing emails to my inbox pitching luxury experiences to the Aspire tier of clients who believe gold plating is a personality trait—my phone lit with a simple message: 9 a.m. Sunrise. 12th floor. Proper attire. My grandfather was not a man who wasted words.

We entered the bank and the marble did what marble does: insisted we feel small. I performed the small trick I have developed for such spaces—I imagined the cost per square foot multiplied by the number of people who would never be allowed to sit on the leather benches by the windows, and I reminded the marble that we made it.

The receptionist greeted me by my last name. The family’s mouthpiece, a woman whose job it was to schedule sorrow for rich people, escorted us to the executive conference room. Richard, Morgan, and Brian were already there, their faces drained of color that money cannot buy back when inheritance looks unsure.

Morgan stood too fast and almost knocked her chair into the credenza. She came forward, hands clasped, and bowed in a way that would have been gracious had it not been marked by the whiplash of now knowing who I was. “Miss Parker,” she said, her voice trembling, “we—that is, I—”

I looked at her as if she were an email asking me to work weekends for “exposure.” “What exactly are you apologizing for?” I asked.

She swallowed. “We… did not know.”

“Not knowing,” I said, “is not the defense you think it is.”

Brian opened his mouth. I set my phone on the table, screen up. He closed it.

“This situation started because I said I would close my account,” I said to the room. “And you told me to go ahead. For me personally, that would be an inconvenience for your teller staff, not a tragedy for your balance sheet.”

Morgan, relieved to be back on numbers instead of ethics, seized the offered balloon. “Yes. Small accounts—”

“But my account is not the only account,” I said.

The door opened. My grandfather entered as if the room had been built to receive him. In a way, it had. Oliver Parker, former CEO of Sunrise Bank, had stepped down ten years ago and had spent the last decade reading books and correcting the grammar of men who wanted to pretend money absolves all sins. He kept his hair trimmed and his enemies trimmed closer. He sat at the head of the polished table without being invited, which is how you know where power lies.

“Oliver,” Richard said, relief cracking his voice, “I’m sure we can sort this out.”

“Richard,” my grandfather said, and drifted an eye over Morgan, whose blood pressure you could see working under her pearls, and then to Brian, who glared at me with a combination of resentment and the lingering allure of a man who thought women were a resource. “You called my granddaughter a commoner with a low background who would complicate your son’s life. In a public place.”

Silence. The conference room absorbs sound the way the ocean does ships—briefly and without remorse.

“We were…” Richard searched for footing. “Teasing.”

My grandfather lifted one eyebrow. Across the polished wood, the recording app on my phone caught the light.

“I recorded it,” I said. I tapped the screen. We all listened to their voices make our case for us. It’s a dizzying thing to hear contempt played back in a space that was built to keep the contempted out.

When the file ended, my grandfather leaned back, steepling his fingers. “Here is what will happen,” he said. He did not yell. He did not threaten. He simply made a list. “One: Natalie’s accounts will be transferred to a different institution within twenty-four hours. Two: you will tender your resignation to the board, Richard. Three: Sunrise will issue a public apology to single-parent families and to customers who have heard the word commoner from the mouths of your staff. Four: you, Brian, will not become CEO. You don’t have the temperament. A bank is not a stage for your nature.”

“You can’t do this,” Morgan hissed. “This is our bank.”

My grandfather turned to her. “No,” he said. “This is my bank. It just has your name on the brass today.”

Richard’s façade cracked. “Oliver, this is over the line.”

“Over the line,” my grandfather repeated softly, as if testing the sound of it. “Is telling a woman who raised her daughter alone that she is too low to sit at your table. Over the line is believing you have the right to grade human beings like meat.” He pointed, and for a second the old CEO materialized in his shoulders, the one whose signature had opened or closed fortunes. “Apologize,” he said, not to me, but to my mother.

Morgan’s face rearranged itself into the shape of something bitten. She stood, trembled, and bowed to my mother. “I am… sorry,” she forced out. “We… I… said unforgivable things. Please… forgive us.”

My mother folded her hands. “Your apology is useful,” she said. “But forgiveness is work we will do at home.”

Brian crossed his arms. “This is ridiculous. Who would think a single parent’s relative was the former CEO? She should have told us.”

“You insulted us without needing prompts,” I said. “Ignorance of somebody’s proximity to power is not a license to kick them in public. The fact that you didn’t know who we were is precisely why you should behave as if everyone you meet matters.”

He sneered. “You set us up.”

“I prepared for a predictable outcome,” I said.

Richard sat down. He did it the way men sit when they know a story has ended and they are not the hero. “Oliver,” he said, “the board—”

“Will thank me,” my grandfather said coolly. “If they have sense.”

He turned to me. “Natalie,” he said, as if there were no one else in the room, “do you want the full withdrawal executed?”

I thought of marble and tuxedos and the way pomp turns men into statues of themselves. I thought of tellers counting cash for people who will never be invited to a conference room. I thought of the bank’s scholarship fund that had paid for books for kids who were me. I thought of power as a hammer and also as a scalpel.

“Not yet,” I said. Four heads jerked. “You know what happens if we yank seven million overnight. People get hurt who didn’t call us names. We will set a schedule that eases pressure on the branches. And we will issue a statement that says why.”

“They will beg for mercy,” my grandfather said matter-of-factly, as if he were announcing a weather system.

“They already are,” I said.

“Please,” Morgan whispered then, dignity retreating before fear. “Please. We made a mistake. We were wrong. Don’t do this to us. Don’t ruin Brian’s future.”

“Brian ruined Brian’s future,” my mother said gently. “We’re simply making sure no one else pays for it.”

Richard changed tactics in that instant the way men in suits do when they need something. “We made a terrible error,” he said. “We will make amends. We’ll make a donation. We’ll—”

“We’ll change your hiring practices,” I said. “We’ll set diversity targets that include class. We’ll create a policy that forbids staff from discussing customer status out of the context of service. We’ll tape a sign behind every teller window that says Wealth is not a personality and you will have to look at it every time you break a hundred.”

“You don’t run this bank,” Brian snapped.

“Unfortunately,” my grandfather said dryly, “she just did more to safeguard its reputation than you.”

Afterward, at my grandfather’s house, he poured my mother tea and handed me a folder. “They will try to reclaim the narrative,” he said. “Tell your truth once and then get on with your life.”

So we did. Sunrise issued the apology. In it, they mentioned single-parent families specifically. They mentioned commoners in quotation marks that did not save them. They announced an internal review of executive suitability, which is what banks call firing someone like Richard without admitting he slept through a decade of ethics workshops. Brian was “exploring new opportunities,” which is what sons of bankers call looking up flights to places where their last name isn’t an impediment. Sunrise’s board asked my grandfather to find a new CEO, which is what people do when their house is on fire and the man who built their water system is standing next to a hydrant.

Richard called me twice to beg. The second time he said, “Natalie, please. Have mercy.” Men like him don’t use that word often; saying it stripped something off him he would never get back. I listened to the word crumble in his mouth and thought of every teller who had asked a manager to waive a fee and been told rules were rules. “Mercy,” I said. It can be a weapon and it can be a bridge. “Ask the board,” I told him. “And ask my mother, while you’re at it.”

He sent flowers. My mother left the card on the table unread and watered the lilies because leaving things to die has never been her style.

The fallout moved like weather. An industry blog picked up my recording where their voices used commoners and low background like pincushions. Sunrise’s PR team flooded the zone with assertions of diversity commitments and community bank values. Comments piled under the post: single mothers and their grown children describing how it feels to be told your life is a stain. Someone photoshopped Richard’s face onto a Monopoly card and wrote Go Back Three Spaces. All of it mattered and none of it mattered because the only thing that fixes contempt is change you can audit.

Brian sent me exactly one message after he resigned: You ruined me. I didn’t reply. The world is not a movie where villains learn after somebody shouts. Sometimes the lesson is being removed from rooms you thought belonged to you.

People expected me to celebrate. I didn’t feel like a victor. I felt like a woman who had been handed a scalpel and told to carve rot out of something she once might have wanted to love. At work, I asked for a raise because being the granddaughter of a power broker should never be the most valuable thing about me. I got it because I had the numbers. At home, I put bowls on the table with more food than we needed because abundance is a practice. My mother returned the bowls to the cupboard with that same posture, the one that has balanced weight since before I was born.

A month later, my friend who had introduced me to Brian approached me sheepishly in the market. “I’m… so sorry,” she said, cheeks pink. “I didn’t know.”

“You don’t have to be sorry,” I said. “You introduced me to my enemy. Then I introduced him to his.”

We laughed in that brittle way women do when we have dodged harm by the breadth of a thread. She squeezed my elbow. “You did good.”

“Sometimes doing good looks like leaving,” I said. “And sometimes it looks like staying long enough to close an account.”

Sunrise installed a new CEO, a woman who grew up in a town like the one my father didn’t come home from. She instituted a staff program called First in Family—paid time off for employees who are the first to graduate, buy a house, take their mother to dinner just because. Sunrise held listening sessions. They ran the risk of feeling like performance; they did the work to make them matter.

I walk past the main branch sometimes. The marble still tries to intimidate, but I keep my little trick in my pocket. I picture the teller windows opening to a woman like my mother, a man like my grandfather, a kid like me who once wanted to crawl under a table in a fancy restaurant and scream. Then I picture all the people who would defend that kid now. It doesn’t make the marble smaller. It makes me bigger.

On the anniversary of the night Morgan called me a commoner, we ate dinner at a tiny place my mother loves because the owner remembers her name. We ordered too much and brought home leftovers, which is a form of wealth I endorse. My grandfather came with flowers he said were “discounted due to exuberant bloom,” which is how he calls big blossoms that scare off men who can’t handle exuberance. We toasted with water because my mother doesn’t drink. We toasted to “families made of choices.”

After dessert, my grandfather took my mother’s plate to the sink and then turned to me. “Natalie,” he said. “You could have ripped their throats out.”

“I know,” I said.

“You didn’t,” he said. “You made them ask for mercy instead.”

“I wanted them to feel what they made us feel,” I admitted. “Small. Afraid. Unwanted.” I thought of the word mercy leaving Richard’s mouth like a tooth. “Turns out I wanted them to learn something, too.”

“That’s the difference between justice and revenge,” my grandfather said. “One feeds you once. The other makes sure the kitchen is still open tomorrow.”

We stacked plates. My mother washed. I dried. Later, in bed, I replayed the moment in the conference room when Morgan bowed to my mother. I don’t know if she meant it. You can’t audit hearts. But you can audit budgets and practices and who gets to sit at the head of a table.

I didn’t want Sunrise to burn. I wanted Sunrise to change. And change is simply a series of decisions made in rooms with fluorescent lighting and no glamour. It’s a policy written with enough teeth to bite. It’s a woman with a recorder in her purse. It’s a retired man dialing a number he still knows by heart. It’s a mother who doesn’t flinch when strangers call her less.

“Commoner,” I whisper to the ceiling sometimes, to see if the word has any power left. It doesn’t. It rolls off the paint like dust.

People will tell you the world belongs to those who walk into marble rooms confident. They are half right. It belongs to those who know where the exits are, who own their accounts, who teach themselves to hold still when the temperature drops twenty degrees and a woman smiles and shows you exactly how much she doesn’t think you belong.

“Please go ahead,” Morgan had said when I asked if we should close our account.

So I did. And then I left the door ajar for everyone else Sunrise had treated like furniture. They walked through, heads up. The marble didn’t move. We did.

Part Two

Sunrise’s apology trended for exactly six hours—half a news cycle—before it sank into the deeper current where reputations settle into habits. That’s where the work had to begin. It did not smell like champagne. It smelled like copier toner and dust and the coffee you brew at 6:15 a.m. because the branch opens at eight and you promised the Saturday manager you’d bring muffins.

In the weeks after the conference room showdown, my grandfather lived on phones. He stopped eating lunch at one and started tapping his fork against the side of his plate while he dictated lists: names of middle managers who had quietly filed HR complaints, retired compliance officers who still took his calls, community organizers who remembered when Sunrise used to sponsor the Little League and not just charity banquets. If there’s a soundtrack for restoration, it’s a pen scratching a legal pad.

My mother handled her end of it as she handles everything—by showing up. She wore blouses she ironed flat as conviction and stood in rooms where staff gathered in folding chairs with Styrofoam cups. When they realized she was the “single mother from the recording,” hands rose like seeds under rain. People told stories that had lived under their tongues: the teller reprimanded for letting a customer cry at her window; the janitor told not to use the front door; the assistant who had learned to swallow being called “honey” because keeping the job was a luxury.

“It is one thing to issue an apology,” my mother said at each meeting’s end. “It is another to hire with it. Promote with it. Set up the break room bulletin board with it. You do that, and you’ll never need to say sorry again.”

Sunrise’s board did not become saints. Boards do not. But they did become nervous, which is the start of wisdom. They appointed an interim CEO named Isha, who had run the risk department so cleanly for so long that people forgot her name was the thing holding the roof on. She asked my grandfather to chair a culture committee, which he accepted on the condition that the committee include “at least three people who don’t own blue suits.” I ended up on it, accidentally and then fully on purpose. The bank needed outside eyes. I had a set and a recording app.

Our first meeting took place in a converted storage room because the main conference room “was booked” by men wearing watches the size of protractors. It didn’t matter. The room had a whiteboard and a waxy plant with three leaves of hope. We wrote Class in blue at the top of the board and then everything that made class bleed into banking: hours that assume childcare you don’t have; forms written in a dialect only lawyers speak; lobby furniture that makes you feel like you should apologize for sitting on it; branch “security” that’s friendly in some neighborhoods and asks for ID in others.

By month three, Sunrise launched a program with a name that did not make me roll my eyes: First Accounts. Zero minimums. No overdraft fees if your balance fell under fifty dollars. Texts you could reply to with questions and get answers from someone whose signature wasn’t Do Not Reply. A poster at eye level that said in big letters: We’re here for firsts. First job. First apartment. First time you felt a bank treated you like you belonged.

It was cheesy. It was also true.

On a wet Tuesday, I brought my mother to a branch two bus rides from our apartment where the pilot had launched. The lobby was full of kids—their hair still wet from the rain, their jackets cheap and brave. A kid in a hoodie that said Hilltop Boxing walked up to the teller and slid a wad of ones under the glass and said, voice cracking, “For my first car.”

The teller didn’t correct his grammar. She counted his money and printed a little receipt and wrote in huge letters on a sticky note CAR and handed it to him to tape to his own passbook later. When he grinned, the branch got two degrees warmer.

“Do you see this?” I whispered to my grandfather when I called him from the sidewalk. “This is the first brick in a new foundation.”

He grunted, which from him is the equivalent of I am proud of you beyond sentences.

The four of us—my mother, my grandfather, me, and the plant with three leaves—sat at that culture table every week for months. I learned to ask boring questions until the boring questions revealed what the fancy ones never would. Who cleans the branch? What time do they arrive? Which door do they use? Where do the pens go at night? If a mother walks in and says she has ten minutes because her bus is in eleven and her boss is a clock, do we help her open an account now or tell her to come back when she has the paperwork we invented so we don’t have to care?

We changed three things no press release noticed and everything else followed them like boats in a wake: 1) Branch hours moved from banker-friendly to customer-friendly in neighborhoods where the bus schedule said so. 2) Teller scripts lost the line “We don’t do that here,” and gained “Let’s see what we can do.” 3) A line added to every performance evaluation: How did you make someone who wasn’t sure they belonged feel like they did? It was fuzzy. It also measured what mattered.

Meanwhile, the people we had left in the dust did what people do when weather changes. Richard vanished into a house that had more rooms than apologies. He wrote my grandfather a letter on heavy stationery that had been embossed by a man who charged by the ounce. He used phrases like lapses in judgment and regrettable remarks. The letter asked for a meeting. He wrote Please. My grandfather called me.

“Do you want me to meet him,” he asked, “or would you rather I tell him to consult the rules of consequences.”

“Meet him,” I said. “But not alone.”

We chose a room in the bank’s basement no nameplate had ever bothered to label. It had a folding table and the smell of reasons to leave. Richard arrived with a haircut he thought would make him look new. He did not shake my hand because men like him do not know if women like me need to be shaken. He shook my grandfather’s and called him “Sir” with a sincerity that would have been useful a year earlier.

“Thank you,” he said. “For seeing me.”

“You were a good steward of numbers,” my grandfather said. “Not of people.”

Richard looked at the table. “I lost the story,” he said after a moment, and for the first time I believed a sentence that came out of his mouth. “I started thinking our customers were balance sheets I balanced rather than people whose balances measured the same things mine does.”

“And your solution was to mock the ones who refuted your story,” my mother said, her voice not unkind. “Stories are easiest when they don’t include people who make them complicated.”

“I am sorry,” he said. He said it loud enough to be recorded but soft enough to be real. He turned to my mother, not to me. “I said things to you that I would put my hand in a fire to take back.”

She nodded. “I accept your apology,” she said. “And I want you to do something with it.”

He flinched. “Anything.”

“You know ten men like you,” she said calmly. “You play golf with them. You share boards with them. Next time one of them says something like what you said, you say something. In the room where I won’t be.”

He closed his eyes. When he opened them, something in his face had loosened. “I can do that,” he said.

He asked my grandfather for a board reference. He did not get one. He didn’t expect it. The new CEO of a community credit union in a county sixty miles away sent him an email anyway. It did not offer him a job. It asked him to help them implement First Accounts. He accepted. I heard, months later, that he rides the bus to work twice a week and sits in the back with his lunch. It works on him the way a gym works on a body you were ashamed of.

Morgan did what women like her do when the floor disappears. She tried twelve jobs in nine months. Event planning, luxury retail, the PTA at a school where everyone pretends they are not interviewing one another. None fit because none came with an entourage. Then my mother called me one evening from a number I didn’t recognize.

“She’s here,” she said, her voice half laughter and half awe. “Serving coffee at the literacy center. Volunteering.”

“Who?”

“Morgan.”

She stayed. She put on her own apron. She did not cut cakes into the equal rectangles she was used to. She learned to ask elders how they like their tea. She did not change the world. She did change in a way I trust more than speeches.

Brian disappeared into a kind of nightlife that looks like life because it’s lit. He sent me one message, a masterpiece of the form: u didn’t have to ruin me. I did not reply. Two years later, I saw his name attached to a start-up designed to “gamify wealth.” It failed because wealth is already a game and the poor people are the pieces, not the players. He gave a podcast interview where he said his “cancelation” had taught him empathy. The comments under it ate him alive and then moved on to a video of a cat.

If this sounds like I watched and tallied, it is because I did. It’s human to keep score against those who threw you a ball they thought you couldn’t catch. It’s also human to set down the clipboard because you have dinner and a mother who laughed for the first time in a long time and a grandfather who naps in a chair with a book on his chest and a basil plant you are determined to keep alive.

Work found me. After First Accounts launched statewide, my grandfather sent my name to a city council member who wanted to start a financial justice task force. I joined and found myself writing plain-language bylaws for things like no more overdraft fees that cost more than the sandwich you overdrafted for. A high school asked me to teach a Saturday seminar called Money for Humans. I brought donuts. I told them the truth: Banks are companies. Companies are people in rooms. People can learn.

The kids asked questions adults are too ashamed to ask. What is compounding interest, really? Why does my mother’s card get declined when there’s money in the account? What is a credit score and why is it like a parent who doesn’t show up until you need them?

I answered. We drew diagrams on whiteboards and used metaphors that would make Harvard MBAs long for a second childhood. We talked about negotiation where you ask for what you need and add thirty percent because men invented numbers. I told them the story of the recording, and they laughed and then went quiet. “You were not born common,” I told them. “You were born crowded. There’s a difference. Don’t let anyone tell you your space at the table is charity. It is physics.”

Sunrise changed its lobby art. It stopped pretending Roman columns mean trust and hung local student murals instead. The marble remained and behaved itself for once.

A year after the restaurant, Morgan asked to meet us. We chose a small diner where coffee refills are still a birthright. She came in with flowers from the grocery store. She did not know how to hand them to my mother. She settled for placing them on the table, fingers trembling.

“I was cruel,” she said. She had practiced the sentence and it wore her. “I thought the world came in boxes. I am trying to make my boxes bigger.”

“We’re not a project,” my mother said softly.

“No,” Morgan said. “You are the people I think about when my friends make jokes.”

“Do you say anything?” I asked.

“I try,” she said. “Sometimes I fail. Sometimes I don’t.”

“That’s the work,” my mother said, and we drank coffee and didn’t toast because we are not sentimental that way. We paid the bill. Morgan tried to take it. My mother let her. Mercy works on both ends of the check.

The restaurant where they had called us commoners went out of business the following spring. It was not a morality play. The lease went up. The landlord raised the rent. The chef wanted to open a place where he could cook food his grandmother would recognize. We went on a Tuesday. It smelled like tomatoes and forgiveness. The menu had a dish called Sunday Sauce. My mother ordered it and cried at the second bite. When the chef came out, she told him he had cooked her childhood. He wiped his hands on his apron and nodded because he was a man who understood how to accept a compliment like a paycheck.

On the anniversary of the day my grandfather walked into Sunrise’s conference room and laid down a list like flooring, the bank hosted a community fair on its front steps. It was corny and perfect. A mariachi band played next to a table where a teller explained routing numbers to a grandmother with a baby on her hip. I watched my mother show a teenager how to fill out a deposit slip. He looked at her with a concentration that made me want to put a roof over his head.

“Richards are made,” my grandfather said into my ear, appearing beside me with the old stealth of men who have learned how to navigate rooms where everyone wants something. “So are Olivers.”

“Do you ever regret building it?” I asked, nodding at the building that had held both good intentions and bad behavior.

He tilted his head. “Regret is for the end of a day,” he said. “This is noon.”

In the late afternoon, when the sun made the marble less smug, a woman I did not recognize approached me. “You’re Natalie,” she said. “I wanted to thank you. My kid opened an account today. He works nights at the grocery, and he hates asking me for cash. His face…” She trailed off. You do not have to describe certain faces. We know them.

“You did that,” she said.

“We did that,” I answered. “And he did. He walked in.”

I keep the recording on my phone still. Not to play it for myself, but to play it for rooms that need to be reminded that contempt is a public health hazard. I have only played it twice since—the second time at a legislative hearing where a man in a suit who looked like he had been born in one called overdraft fees “a necessary disincentive.” I looked at my mother in the front row. She lifted her chin. I pressed play.

I am dating someone now. He is not a banker. He fixes saxophones in a shop that smells like old music and oil. He is not impressed by marble but he knows the price of a reed and the cost of a bad note. When I told him the story of the restaurant, he said, “You must have been terrified.” I laughed because nobody had asked me that. I told him the truth.

“Not at the table,” I said. “Only afterward. Fear is a thing that catches you when you’re safe.”

He makes me mixtapes like it is still 1998. He wrote Commoner on one in thick black marker and then added underneath, A person belonging to a community. I hung the case on my wall next to the three-leaf plant, which became five and then seven because tending things is contagious.

I still take my mother to the small diner with the refill coffee and we talk about everything but banks. She still keeps her back straight. When someone makes a joke about single mothers on television, she throws a dish towel at the screen. I buy her flowers with exuberant bloom and we place them where everyone can see them from the street.

Sometimes, when I am alone in my apartment and the late light makes everything look like forgiveness, I think about the moment in the restaurant when I asked if we should close our account with Sunrise. I think about Morgan’s flippant “Please go ahead.” She thought she was dismissing me. She was granting permission I did not require but took anyway, because sometimes rebellion looks like doing exactly as you were told—just bigger.

They begged for mercy. They got terms. Mercy dished without terms is pity and pity is just another word for contempt that looks like a hug. Mercy with conditions is a bridge you can cross if you’re willing to stop throwing rocks from it.

If you are reading this because you were told you were a commoner in a room where everything was built to make you believe it, I have exactly one piece of advice: record the moment. Maybe with your phone. Definitely with your memory. Then build a list and a team and a habit of showing up. Close the account they invited you to open with your humiliation. Open another with your name on it and rules you helped write.

The marble will not move. You will.

END!

News

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister My House At My Birthday — Then The Secret Board Files Appeared…. Part One…

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… CH2

I Told My Mom About My Son’s Emergency, But She Chose to Insult Him… Part One The emergency room’s…

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

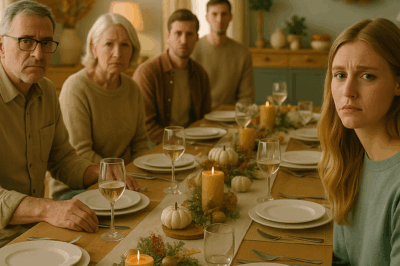

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead. CH2

Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead Part…

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My ‘Affairs’ At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… CH2

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… Part One The first…

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load