My Dad Smashed My Laptop On My Head Before Final Thesis—Said “Leech, You Don’t Deserve a Future”

Part One

My name is Casey, and everything I built began in a one-bedroom apartment where the stove limped and the faucet coughed and the textbooks towered over furniture like new architecture. I was the first in my family to make it to college and, apparently, the first to be resented for it. I poured lattes at dawn, tutored kids whose parents signed checks larger than my rent, and studied until the words on the page blurred into a grey river. I was always tired. I was always reaching.

Three days before my final thesis was due—seventy-two hours between me and that door with the word future carved into it—the hatred in our home thickened into something you could smell. We were four people in a space better designed for two and a dog: my father, who wore anger like an old T-shirt; my mother, who had long ago decided silence was safer than sides; my sister Savannah, who knew how to receive; and me, who knew how to go without.

“You’re twenty-four and still here, still sponging off us like a damn parasite,” Dad would grumble, shirtless in his throne—our stained recliner. The beer can he tossed when he was finished talking never hit the wall on accident. It was punctuation.

“Don’t worry, Daddy,” Savannah would say in her baby voice, which had somehow survived adolescence intact. “Once Casey fails her little essay, she’ll finally learn to clean floors like the rest of us.” The rest of us meant me and Dad. Savannah did not clean floors. Savannah curated a life of crisis and expertise in getting out of it. She had dropped out of high school—twice—got pregnant at seventeen, and every time she hit a wall, my parents rolled out red carpet and called it a blessing. She got a car and a shower of pink plastic gifts; I got a bus pass and the reminder that selfish girls don’t give their parents grandchildren.

They didn’t want me to finish. I knew that the way you know rain is coming even when the sky is tricking everyone else.

My laptop was my rib cage. It held the organs of my last five years: notes written at 2 a.m. with hands that smelled like espresso; diagrams drawn between bus routes; 3D renderings of a prosthetic spinal column you could assemble like a child’s toy in a rural clinic with one outlet and two nurses; late-night brainstorms that felt like breaking into a locked room and finding a bed. My adviser said if I built it right, it could change lives.

“Look at her,” Dad said one night, a smear of grease across his chest. “Walking around with her fancy words and typing like she’s about to invent the cure to broke.” He reached for my laptop charging on the kitchen table like a slumbering animal. I stepped between them, the way good daughters are trained to do. “Leave it,” I said. “I’m almost done.”

He didn’t slap. He shoved. Back into the cabinet. The plates rattled. Savannah, leaning against the doorframe with her phone held high, laughed and cooed to an audience she made up: “Daddy, maybe she should use a notebook like in the old days. Trash shouldn’t be allowed tech.”

“I should’ve tossed her when she was born,” Dad muttered, a tone that had once meant jokes and now sounded like archaeology. “Never cried. Just stared like a little leech sucking life through the silence.”

I stood. I picked up my laptop. I walked into my room. I whispered into the air, “Three more days,” because sometimes the only person you can make a promise to is yourself.

The next evening the house was unusually quiet. Only the living room lamp burned, throwing a cone of yellow on the coffee table. Savannah sat on the sofa with a smile that belonged to the devil in old cartoons. Dad stood behind her, that light catching the ridge of his collarbone like a ridge in a map. My laptop lay on the floor.

At first my brain refused to understand what my eyes described. Then I saw the crack running right down the middle of the screen, the lid dented like someone’s knuckles had argued with it. The hard drive was a small exposed heart.

I fell to my knees. My scalp prickled. Breath threatened to reverse.

“I told you,” Dad said. He smiled like he had just found a dime in the dryer. “This house doesn’t serve leeches. Leeches don’t get futures.”

I looked up. My mouth had dried into something chalky. “Why?”

“Because you got cocky,” he said. “Thought you could fly above this family. Guess what? We keep our own on the ground.”

Savannah leaned forward and peered at my face the way entomologists peer at pinned butterflies. “Oops,” she said brightly. “Looks like Miss Perfect doesn’t have anything to submit now. Shoulda saved it to the cloud, genius.”

I heard the sound of my own breath and realized I had two choices. One was to break. The other was to build something from the pieces of me that remained. But not here. Not in front of them.

I stood. The room tilted. I gathered the wreckage of my machine like a mother collects the parts of a toy she cannot fix yet. I did not curse. I did not sob. I did not give them the performance they were waiting for so they could call me dramatic.

“Don’t go mute on us now,” Savannah sing-songed. “You’re not even bleeding.”

I smiled. It startled her because it wasn’t for her. It was for me. It was the first time in weeks my face had remembered the muscle.

They didn’t know what lived in me.

They didn’t know my project was no longer a nest of zeros and ones. It had moved into my hands and the hollows above my eyes and the place pain usually goes. Every sketch had been rehearsed a hundred times. Every calculation was a prayer learned by heart. I could rebuild. I wouldn’t just rebuild the project. I would rebuild everything.

The next morning, I left without speaking. Not because I was scared. Because silence is a tool if you refuse to let other people use it against you.

The lab smelled like solvents and effort. Dr. Ellis looked up from a stack of papers and saw the swelling along my hairline where the corner of the laptop had connected with me on its way down. The face she made was the kind you save for people you call family when they get old. “Casey, what—”

“I need access for the next three days,” I said. “I’m rewriting.”

“You have seventy-two hours,” she said softly. “That’s more than enough.”

It was not. But you can bend time if you put both hands on it and push.

Part Two

For two days, I didn’t sleep. I lived inside the lab like it was a pocket I could crawl into and stitch shut from the inside. I dragged fragments from the university simulation drive: the skeleton of a draft, a map of a machine, the first paragraphs of a literature review. I rebuilt what I could from memory. I upgraded more. That’s the secret they don’t tell you about losing everything—once the fear of breaking keeps breaking, you stop fearing it. My adjusted hinges flexed better in the model than they had before. The new polymer lowered the cost projection by thirty percent. At 3 a.m., I ate crackers on the floor and wrote captions for figures with hands that no longer trembled.

On hour sixty-nine, my shirt smelled like boiled beans and stale coffee and the inside of a textbook. My hair looked like a brush had given up on the idea of order. I hit submit. Then I slid under my desk and slept like someone who has crossed out a word and written a new one in black ink.

When I woke, my phone looked like it had been trying to rescue me all night. Twenty-four missed calls from Savannah. Two from Dad. No messages. They never leave trail; they leave bruises.

Presentation day smelled like nerves and too much dry-cleaner. The hall was full of suits that made men walk too stiff and heels that would do their wearers no favors in the snow. I wore a black sweater with holes in the cuffs that my fingers found. “Casey Monroe,” Dr. Ellis said into the mic, and the room went the kind of quiet you can slice bread through.

I clicked to the first slide and forgot to be terrified. I spoke like someone who had already been punished for wanting to stand. I spoke like someone who had watched a man break and then decided the breaking didn’t belong to him. I explained prosthetic spinal columns and why rural clinics would rather ask for miracles than money. I walked them through polymer choices and why hinge design matters where power sources do not exist. I showed cost models that said you can save a child’s ability to walk for the price of a car battery and two nights at a roadside motel.

I ended on a slide I had digitized from a napkin in a motel room. A little girl drawn like a stick figure because that’s all I had when I did not have time for proportions. A brace down her back. Bare feet. An arrow pointing to a future with the word upright written in the margin.

Silence. Then the kind of applause that made my ribs ache again.

I didn’t just pass. I won the dean’s thesis honor. They pinned my name to a corkboard that used to make me pause on my way to the elevators and think the word impossible. The fellowship board added me in a line that would make my father’s mouth mispronounce pride if it ever tried to escape.

I waited three days to go home. Not for drama. So I could figure out, inside a motel room that smelled like disinfectant and secondhand grief, how you leave a place that does not believe you deserve to go. The answer is to pack quietly. I bought a cheap duffle bag at a pharmacy at midnight. I wrote never again on a sticky note and put it on the inside of my shoe. I printed one copy of my thesis because the man in the copy shop looked like he liked to see people succeed.

Savannah was in the kitchen when I walked in. She had the kind of look you wear when you have discovered that other people’s cheers do not automatically quiet your own dread. “You made me look like a joke,” she hissed, shoving her phone toward my face.

“Do you know what it’s like to have your friends tag you under your sister’s posts? OMG genius, we stan Casey. What do you think that makes me look like?”

“Unemployed,” I said. I did not say it with glee. I said it like I was reading a bus schedule aloud.

She moved toward me and stopped because I looked at her the way restraining orders do. “Touch me,” I said quietly, clearly. “And the police will arrive faster than your next lie.”

Dad stormed in like he had hoped the floor would swallow me on sight. “Where the hell have you been?”

“Winning,” I said.

“This house doesn’t care about trophies. You still live here, still breathing our air, still eating our food.”

I pulled an envelope from my coat and handed it to him. A check. Ten thousand dollars. He stared at it as if numbers had betrayed him. “What’s this?” he barked.

“Rent,” I said. “For the last two years. Adjusted for utilities. Taxes included. Grocery spend itemized.” I had never seen confusion make a man so angry.

“And now,” I said, “you will never say I owe you anything again.”

Mom peered around the corner like a houseplant trying to decide whether it could survive in this light. She said nothing. She always said nothing when something might have changed the narrative.

“I got a job offer,” I said. “Medical design. Full benefits. Across the country.”

Savannah spat, “Where?”

“Somewhere you’ll never live,” I said. I walked out, duffle over my shoulder, and was halfway down the block before the chair in the living room hit the ground like a temper.

I mailed them a package three weeks later. Small. Brown. Labelled in thick marker: from your leech. Inside was my first medical journal offprint, my prototype under the header promising. Taped to the front: a sticky note that read, You smashed my future, so I built another.

They didn’t reply. People like them never reply when the only words available are we were wrong. They wait for your apology like a salary they didn’t earn.

Six months later, in my new apartment with floor-to-ceiling windows and a view of something that did not look like a ceiling painted beige, an unknown number rang. I let it go to voicemail. Savannah’s voice filled my kitchen, ragged and urgent. Dad lost his job. Mom was sick “for real this time.” We need you. Please call. I replayed it and then deleted it. Not cruelly. As self-care.

The email from my old high school arrived the same week. A physics teacher who once told me quiet girls can be smart but loud girls are distracting now wanted me to speak at their Women in STEM day. I almost wrote no. Then I understood that this was not for them. It was for the junior sitting in a classroom chewing the end of her pencil and learning the word leech like a weight.

The gym smelled like bleach and old trophies. I wore a black dress because now I get to choose who I am when I walk into a room. They introduced me as Dr. Casey Monroe. When I stepped onto the stage, I saw them—second row, three faces I had once loved out of habit. Mom’s hair had surrendered to grey, the dye grown out. Dad’s body had decided to soften where he had always armed himself. Savannah looked hollow around the eyes in a way money cannot fill.

I didn’t address them. I looked out at the girls with the crooked ponytails and the knees that still had accidental bruises. “Good morning,” I said. “When I was seventeen, I was told I wasn’t built for brilliance. That my questions made me difficult. That my size in a room would be measured by the space I allowed others.” A hundred heads leaned forward. “No one told me those were powers.”

“I prepared a thesis that someone smashed, physically smashed, because he believed I did not deserve a future,” I said, and paused long enough for the word to land where it needed to. “I rebuilt it in three days—not because I am exceptional, but because I stopped letting people write my ending.”

I did not say my father’s name. I didn’t need to. He heard himself anyway.

After the line of girls with palm-sweat hands and shy questions stopped, I walked out into the parking lot. They were waiting. Savannah’s face had softened into something that looked like remorse if you didn’t know how much practice performance takes. Mom spoke first. “Casey, honey, can we talk?”

“No,” I said. Not loudly. Not unkindly. Like a doctor saying, you need to rest.

Dad tried for the old script. “Families fix things,” he said.

“Families show up,” I said. “You didn’t.”

I reached into my coat pocket and handed him a flash drive. “My new patent,” I said. “Production begins next year. This is what it looks like when a leech becomes a cure.” His hands trembled. He looked smaller than the chair he had once thrown.

“I’m sorry,” Savannah blurted. “I was jealous and it made me cruel. You became what I never could.” It wasn’t enough and it wasn’t for me and it wasn’t on time.

I turned away. “You had the house,” I said, not turning back to watch the words land. “You had their lies. I still won.”

That night I lit a candle in my apartment and did nothing else that looked like victory. No revenge blog. No press release. Just quiet. The kind you earn. The kind that wraps around you like a coat after a winter you thought might never end.

Revenge, it turns out, wasn’t watching them suffer. It was the knowledge that every time they told the story of me, their mouths would wrap around the words we didn’t show up. That on the day I took my future back from their fist, I did not become them. I built something else. And then I walked toward it without looking over my shoulder.

END!

News

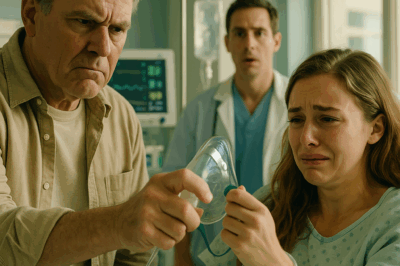

At the Hospital, When I Needed Surgery, Dad Took My Oxygen Mask Off —Save It for Someone Who Matters. CH2

At the Hospital, When I Needed Surgery, Dad Took My Oxygen Mask Off — “Save It for Someone Who Matters”…

On My 25th Birthday My Parents Blindfolded Me for a “Surprise”Then Dumped Me Outside a Dog Shelter. CH2

On My 25th Birthday My Parents Blindfolded Me for a “Surprise” Then Dumped Me Outside a Dog Shelter Part One…

“Before My Marathon Race, Dad Smashed My Ankle With the Baton — ‘Your Legs Were Never Made to Win. CH2

“Before My Marathon Race, Dad Smashed My Ankle With the Baton — ‘Your Legs Were Never Made to Win” Part…

My Sister Gave My Child Expired Food While Her Dog Got Steak — My Parents Laughed “It’s just Expired. CH2

My Sister Gave My Child Expired Food While Her Dog Got Steak — My Parents Laughed “It’s just Expired” Part…

After I Lost My Baby Mom Laughed Finally One Less Useless Mistake Breathing Out Air. Dad Laughed. CH2

My Parents Laughed When I Lost My Baby—“Finally One Less Useless Mistake Breathing Our Air.” Dad Laughed. Part One The…

My DIL: “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing!” “This party is not for you!” CH2

My DIL: “Oh please, your pennies mean nothing!” “This party is not for you!” Part One It should have…

End of content

No more pages to load